tobacco smoking cessation

- related: General

- tags: #note

Tobacco use remains the most common cause of preventable death in the United States. It is implicated in the development of multiple malignancies, pulmonary diseases, and cardiovascular conditions, and all-cause mortality is three to five times higher in smokers than nonsmokers. Tobacco use has been associated with an increased risk for several cancers, reproductive disorders, peptic ulcer disease, osteoporosis, certain pulmonary infections, diabetes mellitus, and age-related macular degeneration. The benefits of quitting tobacco use begin immediately, and over decades, risks for many of the associated conditions decrease substantially.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians ask all adults about tobacco use, advise them to stop using tobacco, and provide behavioral interventions and approved pharmacotherapy to adult tobacco users (Table 78). Abrupt cessation of tobacco use may result in higher long-term abstinence rates than gradually decreasing use. Combining behavioral counseling with pharmacotherapy is more effective than either modality alone. Effective counseling and behavioral resources include problem-solving guidance (such as developing a quit plan and overcoming barriers), motivational interviewing, social support, and telephone quit lines. There is a dose-response relationship between the intensity and frequency of counseling and quit rates, which seem to plateau after 90 minutes of total counseling.

Tobacco cessation treatment

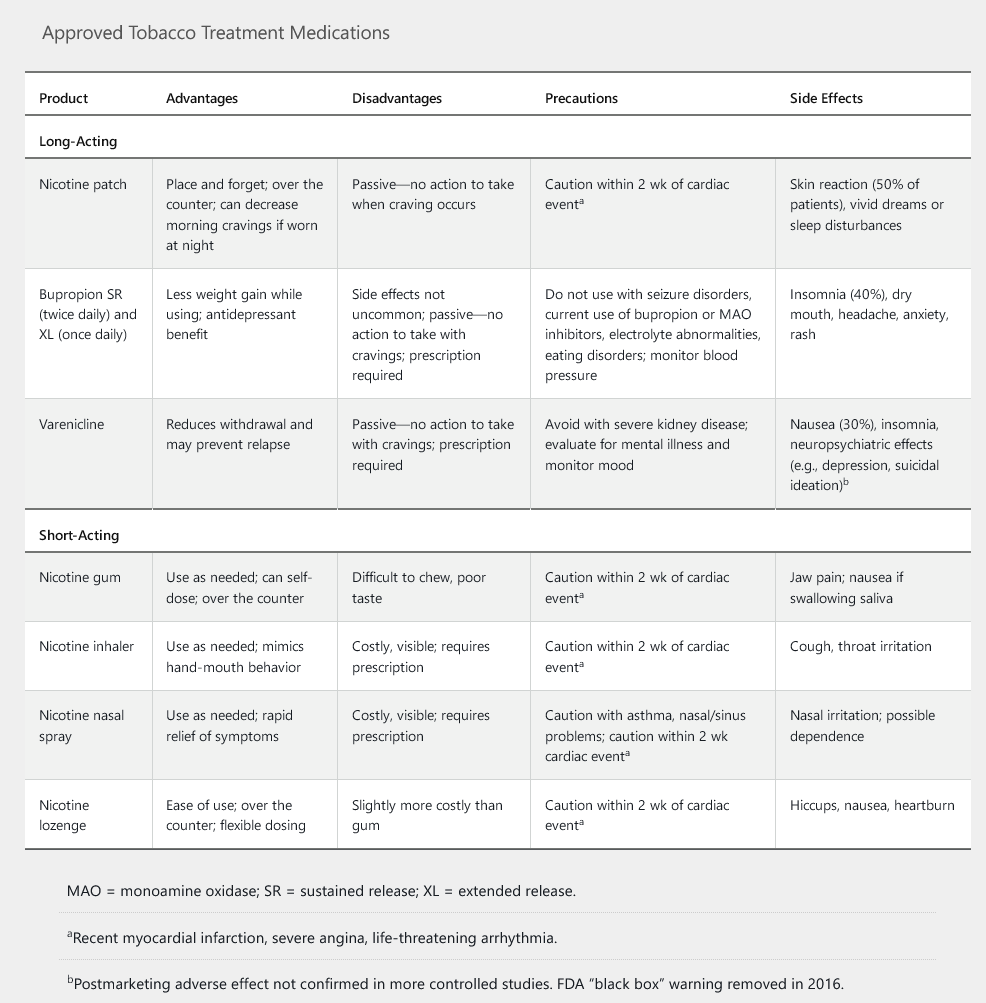

All smokers without contraindications should additionally receive at least one of seven FDA-approved treatments for smoking cessation (Table 79). Varenicline is superior to other treatments, and combining varenicline with nicotine replacement is the most effective strategy. Moderate- and high-dose preparations of nicotine replacement therapy are more effective than lower-dose ones. Combining more than one type of nicotine replacement therapy (short-acting and long-acting) is more effective than monotherapy. Initiation of therapy, especially varenicline, before smoking is stopped may also increase quitting success rates.

Varenicline is a partial agonist at the alpha-4 beta-2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and the most effective single intervention for smoking cessation. Partial agonism of the nicotinic receptor decreases nicotine withdrawal and cravings for smoking. Despite initial concerns about possible serious adverse neuropsychiatric effects from varenicline, the black box warning for these adverse effects was removed in 2016. Based on newer findings, varenicline does not appear to increase the risk of suicidality or depression compared to placebo. There also appear to be no differences between the rates of serious psychiatric symptoms in patients taking bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or varenicline. A history of depression is not a contraindication to varenicline treatment. However, a cautious approach would suggest a discontinuation of varenicline if any new neuropsychiatric symptoms emerge soon after starting this medication. Varenicline should be avoided in patients with current unstable psychiatric status or recent suicidal ideation.

Varenicline has also been associated with a possible increase in cardiac events (eg, myocardial ischemia, arrhythmia), especially in patients with known cardiac disease; but the risks are minimal. Any risk is likely outweighed by the benefits of smoking cessation, and **cardiac disease is not an absolute contraindication.

E Cigarettes

Tobacco use has decreased overall in the United States; however, increasing use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (also known as e-cigarettes and vaping), particularly among young people, is creating new health concerns because their long-term health risks are not yet fully understood. Although e-cigarettes may have a benefit of harm reduction for established smokers, they have been independently associated with the development of respiratory disease; combination use of combustible tobacco products and e-cigarettes may be particularly harmful. Additionally, the nicotine-containing aerosol of e-cigarettes includes other chemicals (such as formaldehyde, propylene glycol, and heavy metals) that may be harmful. E-cigarette, or vaping, associated lung injury (EVALI) may occur and result in severe acute pulmonary disease and death. EVALI appears to be strongly linked with vitamin E acetate, a substance that may be present in some tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing e-cigarette or vaping products. Use of e-cigarettes may also act as a “gateway” for young people, leading toward smoking more traditional tobacco products. The National Academy of Sciences has concluded that e-cigarettes are not without biological effects, including dependence, although not to the extent of combustible tobacco cigarettes. The implications for long-term effects on morbidity and mortality remain unclear.