phenytoin toxicity

- related: pharmacology

- tags: #note

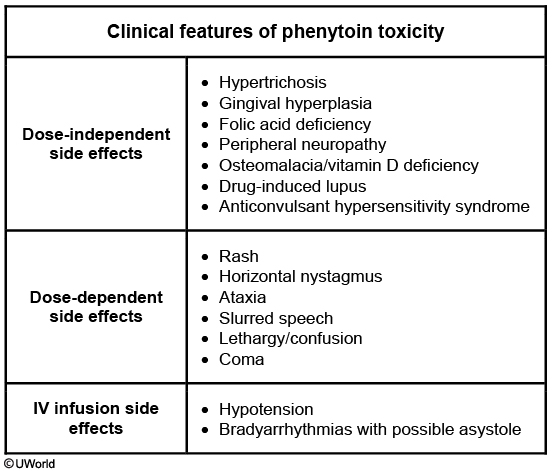

This patient's presentation suggests phenytoin toxicity. Early signs of toxicity include horizontal nystagmus and gait unsteadiness. These may be followed by slurred speech, lethargy, confusion, or even coma. Bradyarrhythmias and hypotension are usually seen with intravenous phenytoin. Toxicity can occur after dosage increase, with drug-drug interactions causing altered metabolism, hepatic or renal disease, or decreased serum albumin. This patient recently started omeprazole, which inhibits cytochrome P450 and leads to increased serum phenytoin levels. However, increased levels are not seen with other proton pump inhibitors (eg, dexlansoprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole).

Hypoalbuminemia results in higher free phenytoin levels that lead to toxicity even when total phenytoin levels are not significantly elevated. Most cases of phenytoin toxicity are managed with supportive care.

It is important to recognize the early signs and symptoms of phenytoin toxicity. The earliest sign is the presence of nystagmus on far lateral gaze. Some other effects include blurred vision, diplopia, ataxia, slurred speech, dizziness, drowsiness, lethargy, and decreased mentation, which progresses to coma. Systemic side effects and neurotoxicity is one of the major limitations to the use of phenytoin.

Usual therapeutic range of phenytoin is between 10-20 mcg/mL and most patients will experience adverse dose related neurotoxic effects with levels greater than 20 mcg/mL. However, the serum levels associated with neurotoxicity vary from patient to patient. Some patients can experience side effects even when the measured levels are within the normal therapeutic range. The first step in the management of side effects due to higher drug levels is to reduce the dose or alter the treatment schedule to minimize the peak drug levels. Therefore, in this vignette, the dose of phenytoin should be reduced and patient should be observed for resolution of nystagmus.

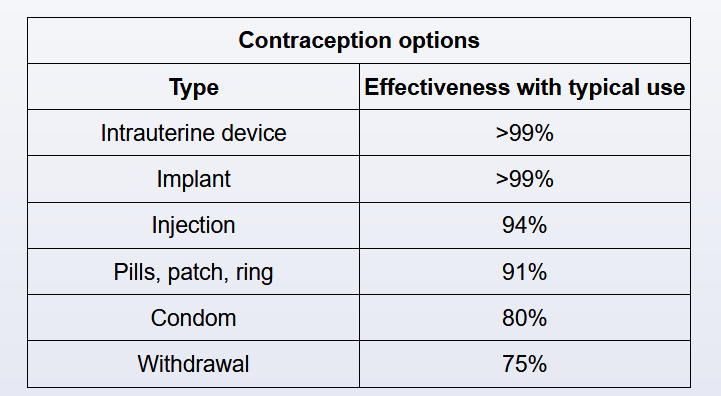

Oral contraceptive pills do not affect the drug level of phenytoin. Conversely, chronic phenytoin therapy can cause failure in contraception by enhancing the metabolism of oral contraceptive pills through the induction of hepatic enzymes.

This patient's presentation of fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia, and elevated transaminases suggests anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS) (a form of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome or drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic [DRESS] syndrome), a rare but serious disorder with a mortality rate of 10%. AHS occurs in about 1/1000 to 1/10,000 patients treated with phenytoin or other aromatic anticonvulsant drugs (eg, carbamazepine, phenobarbital). Other implicated agents include nonaromatic anticonvulsants (eg, lamotrigine), allopurinol, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, antidepressants, and beta-blockers.

Patients usually present within 2 months of starting anticonvulsant therapy with fever, rash, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, and systemic organ involvement (eg, hepatitis, nephritis). Rash can present as classic erythematous papules, pustules, or possible toxic epidermal necrolysis. Eosinophilia and anemia are common, and severe cases may present with megaloblastic anemia, hepatitis, and rhabdomyolysis.

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion. AHS management includes supportive care and prompt discontinuation of the offending drug. Systemic corticosteroids are frequently used as they may help with faster recovery. AHS patients are at risk for recurrence and development of similar reactions to other anticonvulsants. Family members should also be counseled as there may be a genetic susceptibility.