normal renal function

- related: Nephrology

- tags: #nephrology

The kidney selectively removes waste while retaining needed substrate, maintains fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, and regulates blood pH. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) measures total nephron filtration of blood and therefore correlates closely with toxin removal and overall kidney function. Early loss of kidney function is difficult to detect because nephron loss is not initially accompanied by GFR changes due to compensation through hypertrophy and hyperfiltration. Other markers of disordered glomerular filtration, such as proteinuria and hematuria, are also indicators of kidney disease that may precede any evidence of reduced filtration.

Biochemical Markers of Kidney Function

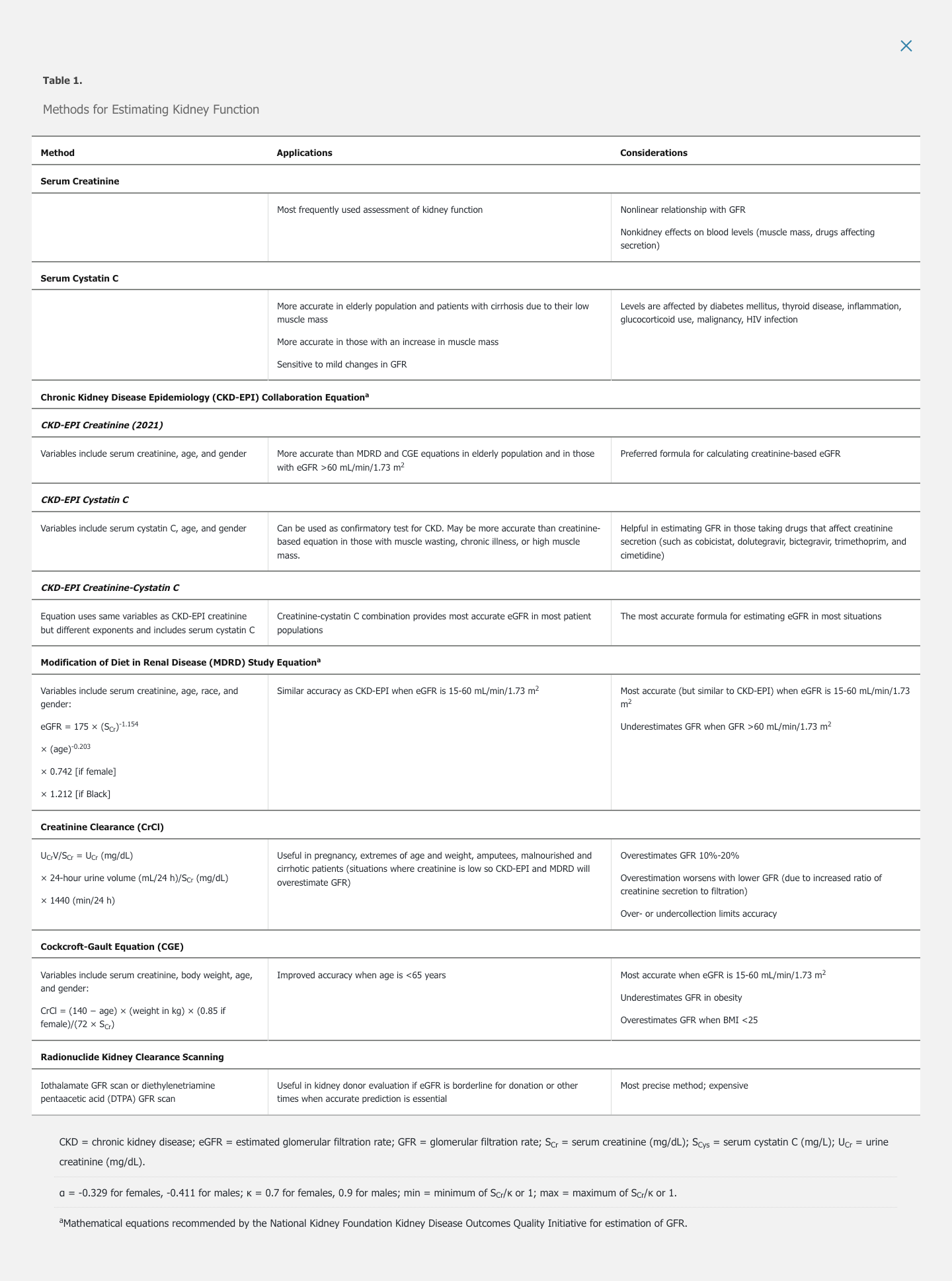

Although numerous methods for estimating kidney function are available (Table 1), serum creatinine and serum cystatin C are the primary biomarkers used to estimate GFR.

Serum Creatinine

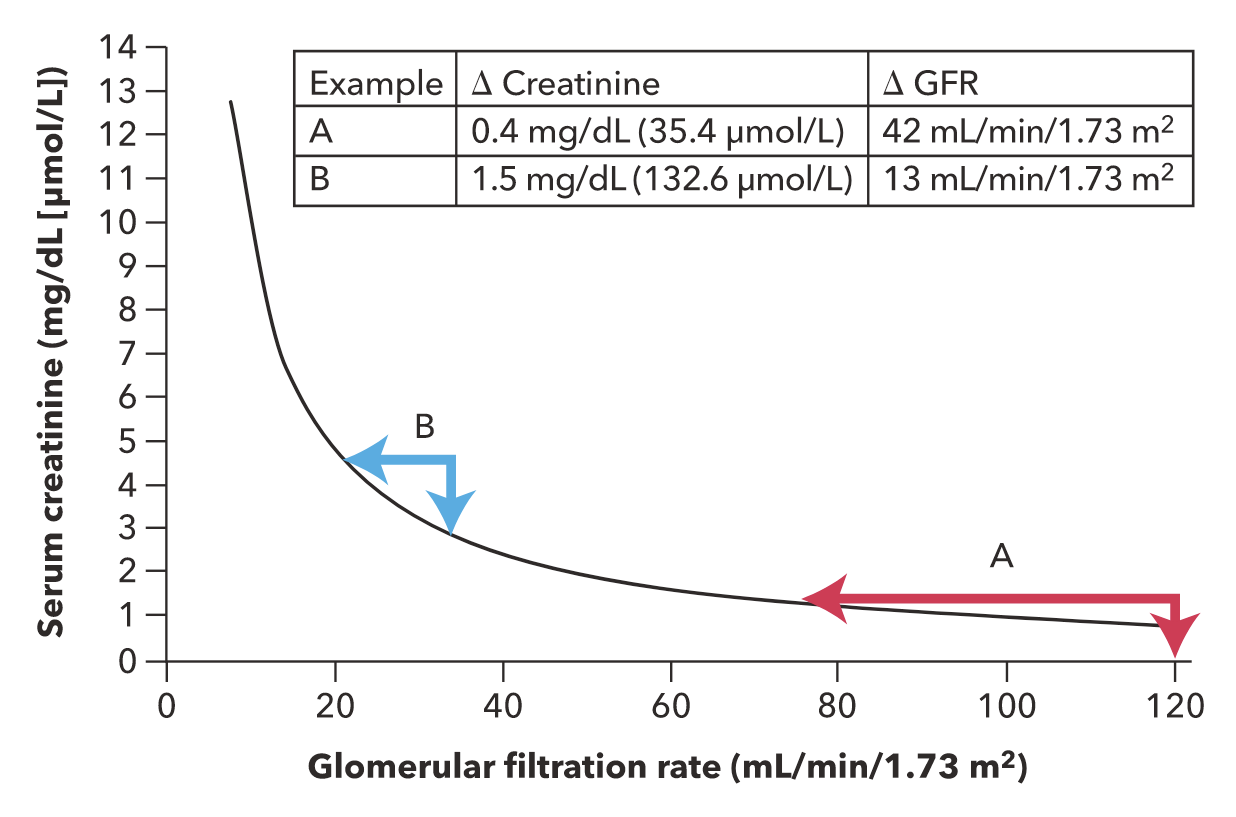

Serum creatinine is the most extensively used measure of kidney function. Creatinine is freely filtered by the glomerulus, without metabolism or reabsorption. Therefore, changes in serum creatinine primarily reflect changes in GFR. However, the relationship of serum creatinine to GFR is nonlinear; significant losses in kidney function at higher GFR may be masked by only small changes in serum creatinine, and small filtration changes at lower GFR are associated with large changes in serum creatinine (Figure 1). Creatinine is also secreted into urine by the proximal tubule, and the contribution of secretion to total creatinine excretion increases as GFR declines. Therefore, when measured creatinine clearance is used to estimate GFR, secreted creatinine will contribute to overestimation of true GFR. With complete loss of kidney function (anuria), serum creatinine typically increases by about 1.0 mg/dL (88.4 μmol/L) per day in patients with average muscle mass.

The relationship between serum creatinine and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Example A illustrates that a small increase in the serum creatinine level in the reference range (in this case, 0.8 to 1.2 mg/dL reflects a relatively large change in GFR (120 to 78 mL/min/1.73 m2). Example B illustrates that a relatively greater increase in the serum creatinine level (in the high range of 3.0 to 4.5 mg/dL) reflects a proportionately smaller change in GFR (35 to 22 mL/min/1.73 m2).

The relationship between serum creatinine and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Example A illustrates that a small increase in the serum creatinine level in the reference range (in this case, 0.8 to 1.2 mg/dL reflects a relatively large change in GFR (120 to 78 mL/min/1.73 m2). Example B illustrates that a relatively greater increase in the serum creatinine level (in the high range of 3.0 to 4.5 mg/dL) reflects a proportionately smaller change in GFR (35 to 22 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Creatinine is a metabolite of creatine, which is mostly present in skeletal muscle. Persons with higher muscle mass (such as younger people, men, and Black persons) have a higher serum creatinine compared with less muscular persons with the same GFR. Loss of muscle mass seen with aging, muscle wasting, malnutrition, or amputation will result in lower serum creatinine despite stable GFR. In persons with decreased muscle mass, serum creatinine therefore tends to overestimate the GFR.

Some medications reduce proximal tubule secretion of creatinine. Such drugs include cimetidine, trimethoprim, cobicistat, and dolutegravir. Resulting increases in serum creatinine occur despite stable GFR. Reassessment of the serum creatinine level 1 week after identification of the increase will confirm the drug's effect.

Serum Cystatin C

Cystatin C is produced by all nucleated cells, freely filtered by glomeruli, and catabolized by tubules. Compared with serum creatinine, serum cystatin C levels are less affected by age, sex, or muscle mass but may be increased by acute disease (such as malignancy, inflammation, or HIV infection). Changes in serum cystatin C may identify small decreases in kidney function better than serum creatinine. Formulas using cystatin C to estimate GFR are helpful for patients in whom creatinine-based GFR may be inaccurate.

- Use cystatin for extreme cases

- wasting patients

- very obese patients

Blood Urea Nitrogen

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) is a product of protein metabolism. Levels increase with reduced GFR and with increased urea reabsorption caused by renal hypoperfusion. BUN is also affected by protein intake and by changes in catabolic rate as caused by glucocorticoids, starvation, or stress. Persons with liver disease have abnormally low levels. BUN may be useful in detecting renal hypoperfusion because elevation of BUN from increased reabsorption is disproportionate to the rise in serum creatinine level.

Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate

Creatinine-based formulas are used to estimate GFR by adjusting for factors that affect serum creatinine and creatinine clearance. These formulas may take into account the effects of age, race, sex, and muscle mass (estimated by weight) on serum creatinine levels (see Table 1).

The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology (CKD-EPI) Collaboration creatinine equation is the most widely used method for estimating GFR and is the most accurate equation for most persons, particularly when GFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. To estimate GFR, the National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology recommend using the CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (2021) , which has been refitted to estimate kidney function without a race variable (see Table 1). The race-based modifier may lead to inaccurately high GFR estimates in patients who identify as Black. CKD-EPI equations presume standard body surface area and therefore require adjustment for very large or small persons. Combining filtration markers (creatinine and cystatin C) into the CKD-EPI creatinine-cystatin C equation is more accurate and informs clinical decision making better than either marker alone.

The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation does not accurately estimate high GFRs. It performs similarly to the CKD-EPI equation at GFRs <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Clinical laboratories that use the MDRD do not report GFRs >60 mL/min/1.73 m2; therefore, physicians may not be aware of the presence of kidney disease. However, an increasing serum creatinine level, proteinuria, or other urine abnormalities should alert the clinician to the presence of kidney disease despite high GFR. The MDRD study equation also requires adjustment for large or small body surface area.

The Cockcroft-Gault equation (CGE) is the least accurate method. It remains in use for drug dosing because it was used in pharmacokinetic studies for most medications.

Creatinine clearance obtained by using 24-hour urine collection is a better measure of GFR than serum creatinine, but it is not recommended for routine estimation of GFR because it is affected by the accuracy of collection and by creatinine secretion.

Radionuclide imaging provides the most accurate measurement of GFR and is the gold standard in research. It is useful for accurate determination of GFR during evaluation of kidney donors, evaluation of recipients for other organs, or assessment of the differential GFR of each kidney before nephrectomy.

Imaging Studies

Ultrasonography is the most commonly used kidney imaging modality. It is easily available, safe, and relatively inexpensive. Ultrasonography can demonstrate hydronephrosis, kidney size and cortical thickness, echogenicity, and presence of cysts and tumors. Absence of hydronephrosis quickly rules out obstruction in most cases. Echogenicity is the ability of a tissue to “bounce back” or return the ultrasound signal and is recognized as brighter shades on the sonogram image. Echogenicity is nonspecific but implies acute or chronic parenchymal disease. Additionally, ultrasonography can measure pre- and postvoid bladder residual, for evaluation of bladder dysfunction or outlet obstruction. Ultrasonography is also useful for uncomplicated nephrolithiasis; a positive ultrasound may be adequate for initial diagnosis. Ultrasonography is less useful in evaluating diseases (including stones) of the mid or distal ureter. Doppler ultrasonography may detect renal artery stenosis or renal vein thrombosis, but is highly user dependent.

CT is appropriate for patients with a nondiagnostic ultrasound or a more complicated presentation. Noncontrast helical CT is the gold standard for diagnosis of nephrolithiasis, and is appropriate for evaluating renal colic. Most stones can be detected, including small stones and those in the distal ureter not detected on ultrasound. It may provide information regarding stone composition and, because the entire urinary tract and abdomen is visualized, alternative diagnoses may be suggested.

CT urography (contrast-enhanced kidney-specific CT) is the test of choice for patients with unexplained hematuria and allows characterization of renal tumors and cysts. CT with contrast is valuable for imaging the renal vasculature. The use of contrast confers risk for contrast-induced nephropathy, particularly in patients with an eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m2.

MRI with contrast is an alternative for evaluation of renal masses and cysts when CT cannot be performed. MR angiography for detection of renal artery stenosis, and venography for detection of renal vein thrombosis, can be performed with or without gadolinium-based contrast, although contrast provides optimal imaging. MR angiography and CT angiography have mostly replaced standard angiography of renal arteries. Due to concerns for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), gadolinium contrast must be avoided in patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. In life-threatening situations in which benefit outweighs the risk for NSF, MRI is performed with low doses of stable gadolinium agents. See MKSAP 18 Dermatology for more information on NSF.

Radionuclide imaging provides the most accurate measurement of GFR and is the gold standard in research (see Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate).

Kidney Biopsy

Clinical and laboratory features are often insufficient for definitive diagnosis of kidney disease. Kidney biopsy may therefore be essential for diagnosis and management. Indications include glomerular hematuria, severely increased albuminuria, acute or chronic kidney disease of unclear cause (in the absence of atrophic kidneys), and kidney transplant dysfunction or monitoring. AIN and atheroembolic disease may require biopsy for diagnosis because they frequently present only with increased serum creatinine. Classes of lupus nephritis are also distinguished through biopsy.

Percutaneous kidney biopsy with ultrasonography or CT guidance is most common. Open or laparoscopic surgical biopsy is performed when percutaneous biopsy is not possible. Contraindications to percutaneous biopsy include the uncooperative patient, bleeding diatheses (including antiplatelet use or anticoagulation), uncontrolled hypertension, poor kidney visualization, atrophic kidneys, and active UTI. Solitary kidney and pregnancy require weighing of risks and benefits.

The most common risks of biopsy are bleeding and injury to surrounding organs. The most common major complications (occurring in <3% of cases) are need for transfusion or angiography with or without embolization, as well as hemodynamic instability. Minor complications include pain and hematuria. Kidney loss and death are very rare complications.