hematuria

- related: Nephrology

- tags: #nephrology

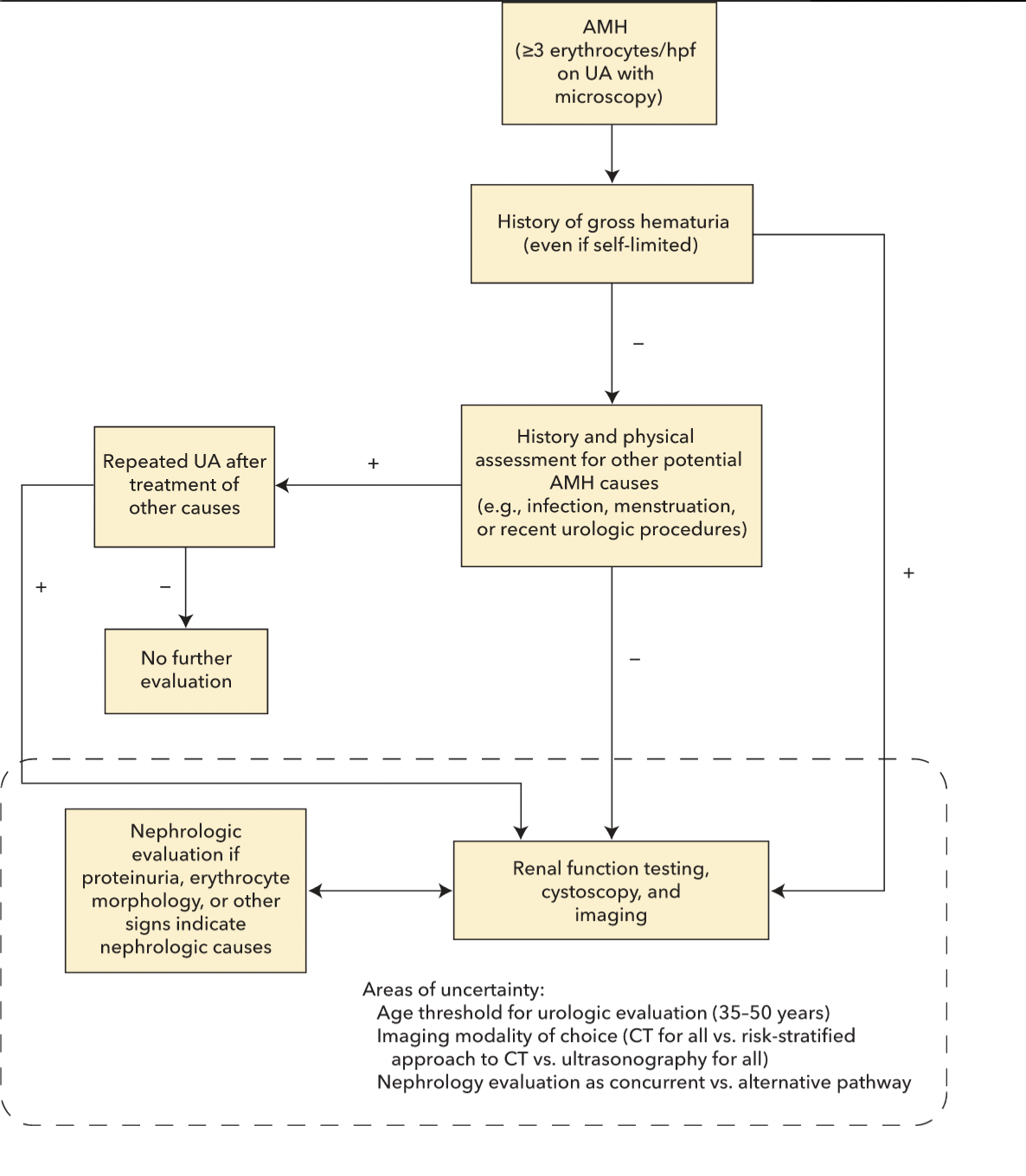

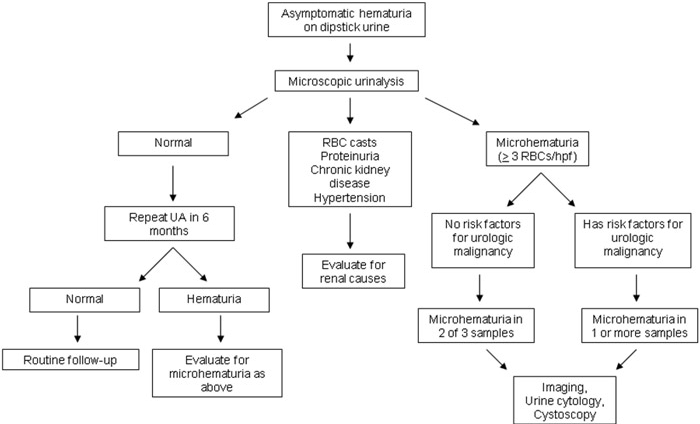

Hematuria is defined as the presence of >3 erythrocytes/hpf in the urine sediment and may be microscopic (detectable only on urine testing) or macroscopic (grossly visible). Hematuria is most often of nonglomerular origin. A glomerular origin is suggested by concurrent proteinuria, presence of dysmorphic erythrocytes, increased serum creatinine or decrease in estimated GFR (eGFR), or systemic signs and symptoms. Evaluation of hematuria is outlined in Figure 5.

Urinalysis should not be used for cancer screening in asymptomatic adults. However, a single incidental finding of hematuria is sufficient to warrant further investigation. Evaluation should be pursued even in patients with bleeding diatheses or those taking antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy. If menstruation, viral illness, vigorous exercise, or some other benign cause is suspected, urinalysis should be repeated after the cause is resolved. If infection is confirmed, urinalysis should be repeated after treatment to document resolution of hematuria.

In a patient with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria, it is important to assess kidney function, erythrocyte morphology, and urine protein to evaluate for a nephrologic cause, particularly glomerulonephritis. The absence of proteinuria generally rules out a glomerular process; exceptions include very mild glomerular disease (most often IgA nephropathy) or thin glomerular basement membrane disease related to a type IV collagen defect that may present as isolated hematuria. Systemic signs and symptoms raise suspicion for nephrologic disease, particularly those associated with rheumatologic disorders and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

Macroscopic hematuria should prompt urology referral even if self-limited, with further evaluation of nephrologic disease and malignancy as indicated.

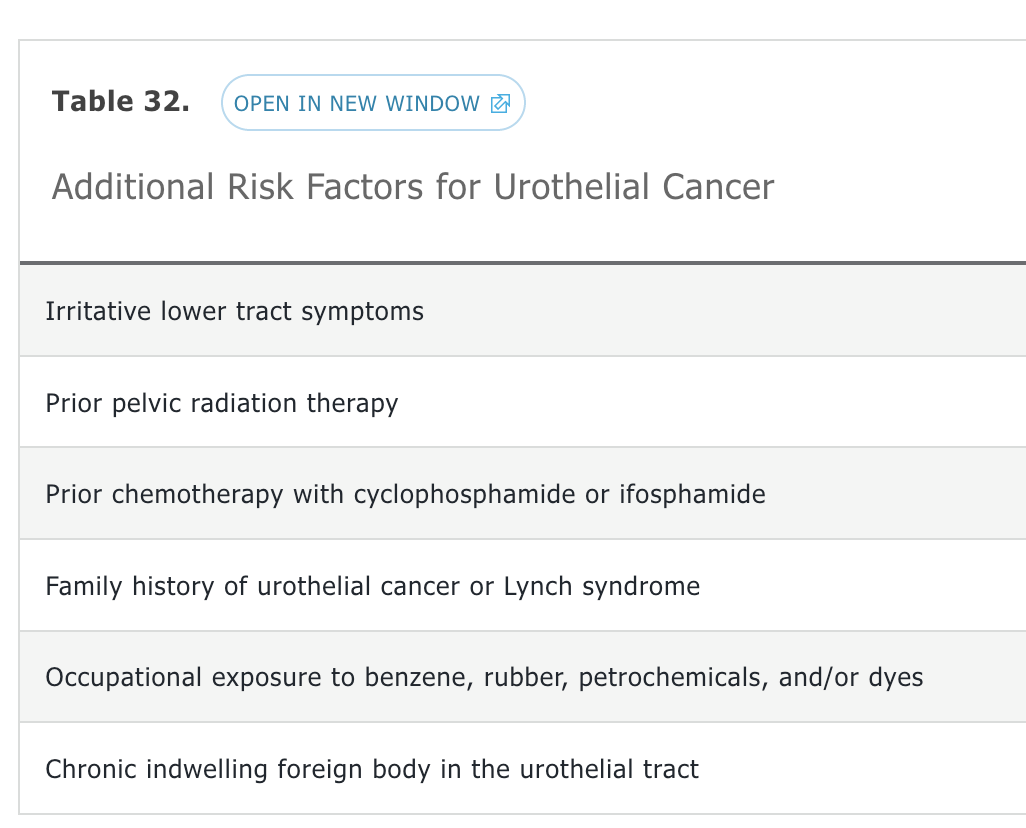

If a nephrologic cause of hematuria is not suggested, hematuria may indicate a malignancy. The American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines recommend stratifying patients as having low, intermediate, or high risk for an underlying urothelial malignancy, with risk status dictating subsequent management. Low-risk patients are women <50 years of age and men <40 years of age who never smoked, have 3 to 10 erythrocytes/hpf noted on a single urinalysis, and have no additional risk factors for urothelial cancer (Table 32). Low-risk patients should have a repeat urinalysis within 6 months and, if normal, require no additional evaluation. If repeat urinalysis continues to show hematuria, these patients are reclassified as intermediate risk (<25 erythrocytes/hpf) or high risk (>25 erythrocytes/hpf). Immediate kidney ultrasonography or ultrasonography plus cystoscopy is not inappropriate for low-risk patients and should be performed if the patient prefers a more aggressive approach. High-risk patients include those with any of the following features: >60 years of age, >30 pack-year history of smoking, >25 erythrocytes/hpf, or gross hematuria. High-risk patients require cystoscopy and CT urography, if there are no contraindications, or MR urography. Intermediate-risk patients include all others and require prompt kidney ultrasonography and cystoscopy. ACP and the AUA recommend against obtaining urine cytology in the initial evaluation of hematuria.