Tick-Borne Diseases

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Lyme Disease

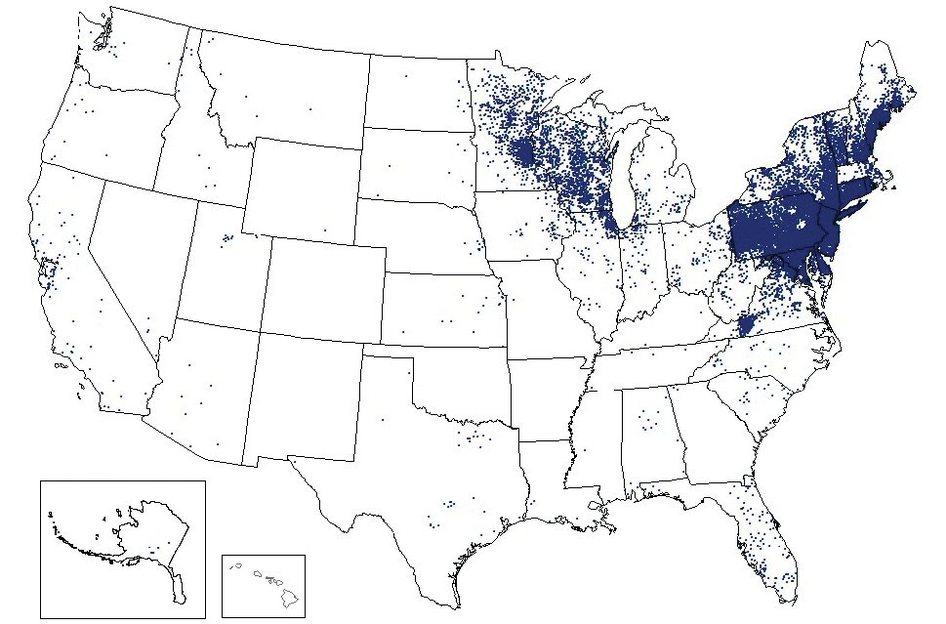

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne infection in the United States. More than 30,000 new infections are reported annually, which likely represent only 10% of actual infections. More than 95% of infections in the United States occur in the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and upper Midwest regions (Figure 5). These areas are endemic for the vector, Ixodes scapularis (the black-legged deer tick). The causative spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, is transmitted intradermally when a tick ingests a blood meal. In Europe, Borrelia garinii and Borellia afzelii cause Lyme disease, with Ixodes ricinus as the tick vector.

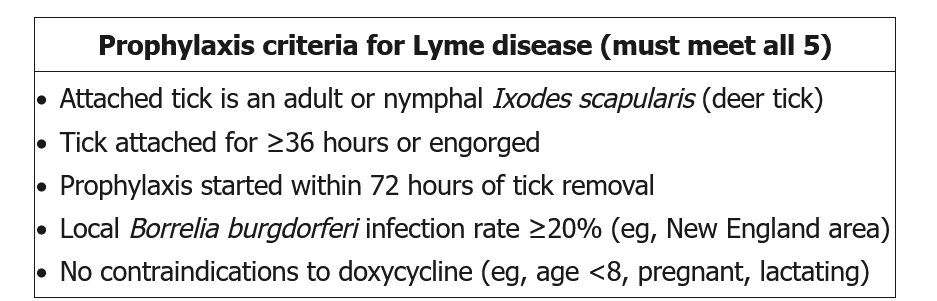

After a tick bite by I. scapularis, administration of a single dose (200 mg) of doxycycline may decrease the risk of subsequent Lyme disease development but should be considered only if (1) the tick is reliably identified as a black-legged deer tick; (2) attachment lasts 36 hours or longer; (3) antibiotics can be started less than 72 hours after tick removal; (4) prevalence of B. burgdorferi infection of ticks in the region exceeds 20%; and (5) doxycycline treatment is not contraindicated. Except for these selected situations, observation is recommended, with treatment given if suggestive symptoms occur.

If the patient cannot take (or refuses) doxycycline, most physicians do not advise prophylaxis with another antibiotic; instead, observation is recommended with rapid treatment if EM develops.

Ceftriaxone is a third generation cephalosporin. It is usually given for second or third stage Lyme disease; however, it is not used for Lyme disease prophylaxis.

The clinical manifestations, diagnostic testing, and treatment of Lyme disease vary according to the stage of infection (Table 16).

Early Localized Disease

Early localized disease presents within 4 weeks of infection. Most infected persons (70% to 80%) develop erythema migrans (EM), an annular skin lesion that often presents with central clearing (Figure 6). Systemic symptoms are variably present.

EM lesions are typically painless, nonpruritic, and circumferentially enlarging. Atypical presentations of EM, with confluent erythroderma, ulceration, or vesiculation, may confound the diagnosis. Local cutaneous reactions due to hypersensitivity to tick saliva may resemble EM but tend to occur earlier, are pruritic, and do not enlarge significantly after onset.

A patient with EM and a compatible exposure history does not require confirmatory laboratory testing. In fact, antibody testing in early localized disease is insensitive because seroconversion may be delayed for several weeks after onset of an EM lesion. Treatment is with an oral agent. Doxycycline offers the advantage of treating incubating Anaplasma phagocytophilum, which also is spread by black-legged ticks and can coinfect patients with Lyme disease.

Early Disseminated Disease

In the absence of treatment, hematogenous dissemination occurs in up to 60% of patients. Symptoms of early disseminated disease present weeks to months after infection. The most common manifestation is a flu-like illness characterized by fevers, arthralgia, myalgia, and lymphadenopathy and often associated with multiple concurrent EM lesions at sites distant from the original tick attachment.

Infection of cardiac tissue results in injury to the conduction system and atrioventricular (AV) nodal block. Progression to complete heart block can occur rapidly despite antibiotic treatment, so hospitalization is indicated for close monitoring of patients with severe cardiac involvement: symptomatic patients with dizziness, syncope, or dyspnea; asymptomatic patients with first-degree AV block and a PR interval of 300 milliseconds or greater; and patients with a higher-degree AV block. Permanent pacemaker placement is not necessary because the heart block is reversible.

Infection of neurologic tissue occurs in approximately 15% of untreated patients. Aseptic meningitis, facial palsy (unilateral or bilateral), and radiculopathy may be present in isolation or associated with skin, musculoskeletal, or cardiac findings. Lumbar puncture is indicated when central nervous system infection (such as neuroborreliosis) is suspected; cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytic pleocytosis supports the diagnosis (see Central Nervous System Infection).

When EM lesions are present, laboratory confirmation is unnecessary. In the absence of diagnostic skin findings, serologic diagnosis should be pursued through a two-tiered approach (Figure 7); the initial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is highly sensitive but lacks specificity and must be confirmed by a Western blot. A modified two-tiered approach that eliminates the need for a Western blot uses different second-step tests, usually a second enzyme immunoassay. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers these tests acceptable alternatives for the laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease.

IgM antibody is detectable before IgG antibody in early infection; however, IgG antibody should be detectable after 30 days of symptoms. Because isolated IgM positivity is likely to be a false positive after the first month of symptoms, testing for IgM is not recommended after this time period. Antibodies may remain for years despite treatment; therefore, serial titers are not useful.

Late Disseminated Disease

Approximately 60% of untreated patients with Lyme disease develop a monoarticular or oligoarticular inflammatory arthritis as a late complication. The knee and other large joints are disproportionally affected. Even without antibiotic treatment, inflammation typically resolves over weeks to months but can have a relapsing-remitting pattern. In approximately 10% of untreated patients, arthritis persists (see MKSAP 18 Rheumatology). Late neurologic or skin findings (acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans and borrelial lymphocytoma) are rare in the United States but more frequent in European infections. Diagnosis is made with the two-tier serologic test. Treatment requires prolonged oral antibiotics; parenteral therapy is used when oral therapy is unsuccessful (see Table 16).

Post–Lyme Disease Syndrome

Post–Lyme disease syndrome has been reported in approximately 10% of patients after treatment of EM (Table 17). Although often erroneously called “chronic Lyme disease,” studies have found no microbiologic evidence of chronic or latent infection after appropriate treatment. Symptoms include fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, and impairment of memory or cognition that can last for years after treatment of the acute infection. Clinical trials have shown no benefit of prolonged antibiotic treatment for post–Lyme disease syndrome. Evaluation for coinfection with another tick-borne pathogen or for a noninfectious cause is indicated; when no alternative diagnosis is found, treatment is symptomatic.

Babesiosis

Babesiosis is caused by the intraerythrocytic protozoan Babesia microti, which is spread by the black-legged deer tick. Because of the common vector, babesiosis occurs in areas of Lyme endemicity (see Figure 5), most frequently during summer months. In Europe, babesiosis is caused by several different Babesia species and is spread by the I. ricinus tick. Transfusion of infected blood products and rare congenital transmission also allows for year-round infection, which may occur outside endemic regions.

Clinical findings range from asymptomatic presentations (approximately 20%) to fatal disease (10%). Risk factors for severe disease include age older than 50 years, immunocompromise, or asplenia. Symptoms begin within 1 month after tick bite and within 6 months after transfusion of infected blood products. Symptoms are nonspecific and include fever (89%), fatigue (82%), chills (67%), headache (47%), myalgia (43%), and cough (28%). Physical examination may reveal jaundice, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly, which rarely progresses to splenic rupture. The hallmark of babesiosis is hemolysis, with anemia almost invariably present. With severe disease, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzyme levels, and acute kidney injury are possible.

Babesiosis is diagnosed by visualization of the causative organism on thin blood smears, manifesting as intraerythrocytic ring forms similar to those seen in malaria or as tetrads resembling a Maltese cross (Figure 8). With low-level parasitemia, multiple smears may need to be examined, and the sensitivity of microscopy is low. Therefore, polymerase chain reaction or serology should be pursued if smear findings are negative but clinical suspicion of babesiosis is high.

Treatment depends on disease severity (Table 18). After treatment, patients should be monitored closely for relapse; if relapse occurs, prolonged therapy extending more than 2 weeks after clearance of parasitemia is necessary for cure.

Southern Tick–Associated Rash Illness

Southern tick–associated rash illness (STARI) presents with EM lesions identical to those seen in Lyme disease but without clinical progression or complications. STARI is associated with Amblyomma americanum, also known as the Lone Star tick, and occurs in the southeastern, south-central, and eastern United States. No infectious cause has been confirmed. Therefore, diagnosis is based on clinical and geographic features. Because STARI and early-stage Lyme disease may be clinically indistinguishable, treatment with doxycycline is recommended.

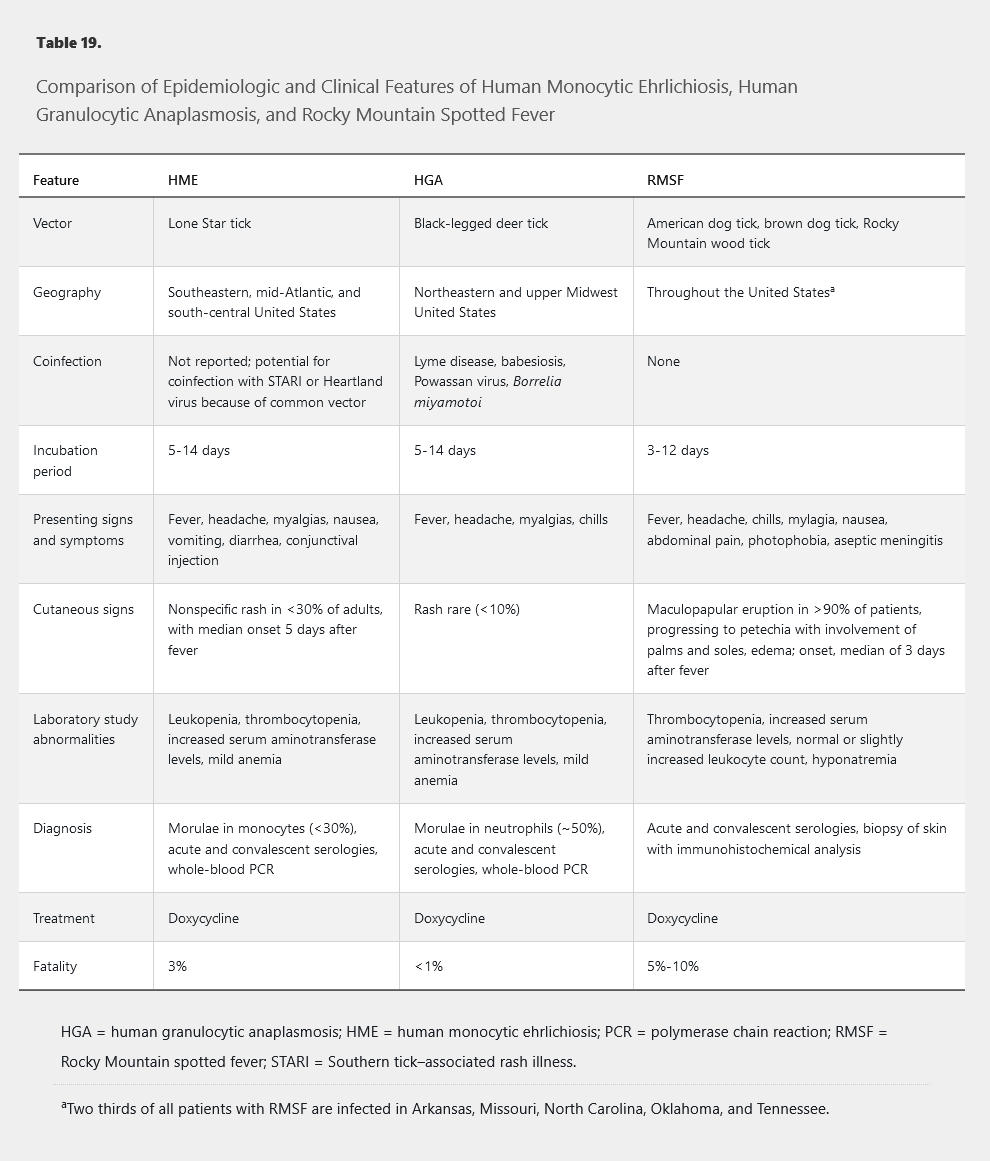

Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis and Granulocytic Anaplasmosis

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) are clinically similar illnesses spread by different tick vectors and caused by distinct bacterial pathogens. HME is caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, which is transmitted by the Lone Star tick, and occurs most commonly in the southeastern and south-central United States. HGA is caused by _Anaplasma phagocytophilum,_ which is transmitted by Ixodes ticks, and occurs in areas of Lyme endemicity (see Figure 5).

Lyme disease cases reported during 2016. Each dot represents the county of residence (not necessarily acquisition) for a confirmed case.

Lyme disease cases reported during 2016. Each dot represents the county of residence (not necessarily acquisition) for a confirmed case.

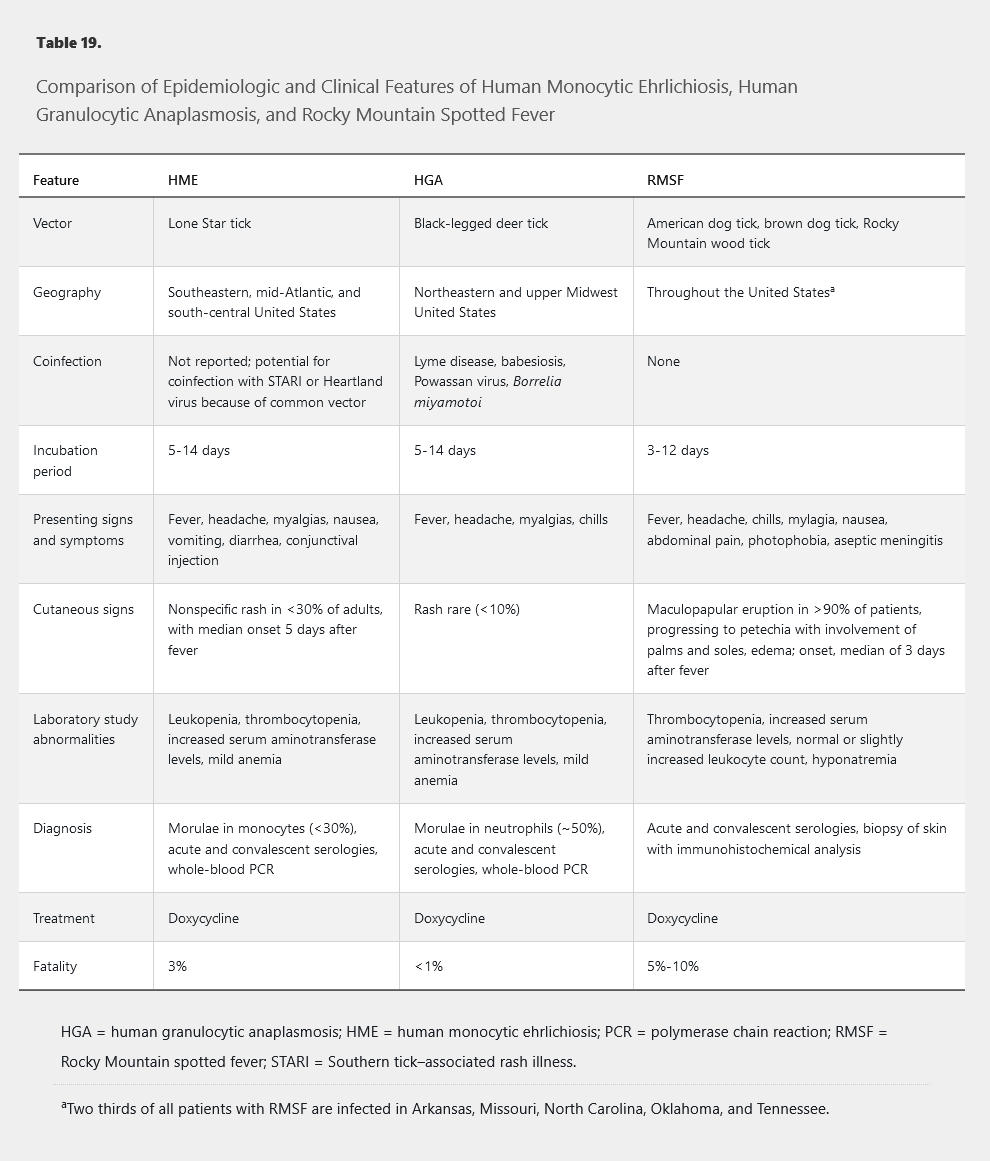

These syndromes typically begin with a nonspecific febrile illness 1 to 2 weeks after a tick bite (Table 19). Rash is uncommon in contrast to Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Laboratory study abnormalities, including leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and increased serum aminotransferase levels, are nonspecific.

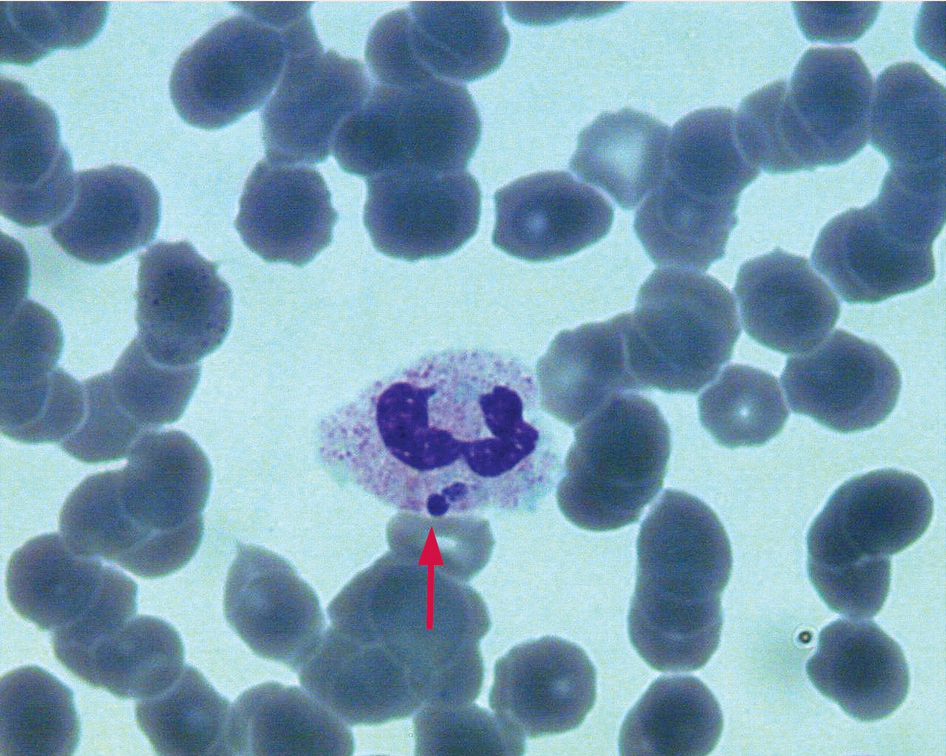

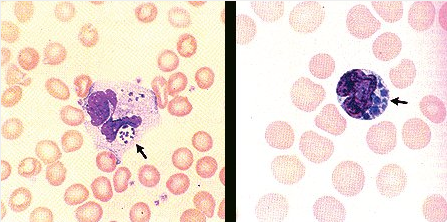

The organisms causing HME and HGA replicate inside leukocytes and cause hallmark basophilic inclusion bodies called morulae (Figure 9). Serologic findings often are negative in acute illness; testing of a convalescent specimen 2 to 4 weeks after onset of symptoms is usually confirmatory. Polymerase chain reaction of whole blood at the time of acute illness may be diagnostic, particularly if performed before therapy. Doxycycline is the recommended treatment for both HME and HGA. Because delay in treatment is associated with increased mortality, empiric therapy should be started even in the absence of confirmatory testing.

Heartland virus, a newly described Bunyavirus transmitted by the same vector as E. chaffeensis, is clinically indistinguishable from HME and should be suspected when no improvement is seen within 48 hours of starting doxycycline therapy.

Morulae (arrow) appearing as basophilic inclusion bodies in leukocytes of a patient with ehrlichiosis.

Morulae (arrow) appearing as basophilic inclusion bodies in leukocytes of a patient with ehrlichiosis.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii and transmitted by multiple tick vectors. It has been reported throughout the continental United States but occurs most frequently in the “RMSF belt” extending from North Carolina to Oklahoma.

Clinically, RMSF presents with nonspecific symptoms similar to those of HME and HGA (Table 19) but can progress to aseptic meningoencephalitis. The hallmark feature is a macular eruption around the ankles or wrists, with central spread and progression to petechiae or purpura (Figure 10). Lesions are found on the palms and soles in as many as 50% of patients; the face is generally spared. Purpura fulminans may occur and result in loss of digits or limbs. Although skin findings are ultimately noted in greater than 90% of patients with RMSF, the earliest macular rash occurs a median of 3 days after onset of fever and thus may not be found at the first clinical presentation.

Immunohistochemical analysis of skin biopsy samples may be diagnostic. As with HME and HGA, acute serology is not sensitive, although testing convalescent serum may provide a retrospective diagnosis. Doxycycline should be given empirically when RMSF is clinically suspected because treatment delay is associated with more severe disease and increased mortality.

Petechial and purpuric skin eruption in a patient with late-stage Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Petechial and purpuric skin eruption in a patient with late-stage Rocky Mountain spotted fever.