Systemic Vasculitis

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Overview

Vasculitis is inflammation of blood vessels, including the capillaries, arteries, and veins. Clinical manifestations result from tissue ischemia associated with the involved vessels. Vasculitis may be primary, secondary to an autoimmune disease, or triggered by other causes (Table 38). Mimics of vasculitis must also be considered in the differential diagnosis (Table 39). Primary autoimmune vasculitis disorders are discussed in this section.

Large-Vessel Vasculitis

Giant Cell Arteritis

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Giant cell arteritis (GCA; temporal arteritis) affects patients over 50 years of age (peak incidence between 70 and 80 years). Most patients are women. GCA is more common in White persons; incidence ranges from 10 to 20/100,000 in Europe. An association with HLA-DRB 04 has been identified.

GCA is characterized by granulomatous inflammation of affected vessels with infiltration of lymphocytes, macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells. Involved vessels include the aorta, its major branches off the arch, and secondary branch vessels, including the external carotid, subclavian, axillary, temporal, ophthalmic, ciliary, occipital, and vertebral arteries. The level of vessel involved dictates the clinical symptoms.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Common GCA symptoms include headache, scalp pain, and temporal artery tenderness. Symptoms are frequently unilateral but can be bilateral. Aching and fatigue with chewing (jaw claudication) indicates ischemia of the muscles of mastication. Fever, fatigue, and weight loss may be present. The most feared complication is ischemic optic neuropathy, which can cause amaurosis fugax and blindness. Because blindness is usually permanent, early recognition and treatment of any visual change are critical. Subcranial disease involving great vessels in the chest occurs in 25% of cases, resulting in upper extremity claudication. Severe but uncommon complications include aortic aneurysm and dissection. Dilation of the aortic root may cause aortic valve regurgitation and heart failure. Up to 50% of patients with GCA have polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) that may occur before, concurrent with, or following diagnosis of GCA.

Physical examination may reveal scalp or temporal artery tenderness and induration, reduced pulses and bruits, or aortic regurgitation and heart failure. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and/or C-reactive protein (CRP), but some have normal values. Nonspecific evidence of inflammation may include anemia and thrombocytosis.

GCA is suspected on the basis of the clinical presentation and is confirmed by temporal artery biopsy and/or imaging of great vessels. New or atypical headache, jaw claudication, or visual changes in a patient over the age of 50 years, especially with concurrent PMR, should raise suspicion. Temporal artery biopsy is diagnostic, but false-negative results are common; bilateral temporal artery biopsy can increase the yield (obtain contralateral biopsy if high enough suspicion). Importantly, temporal artery biopsy will remain abnormal for up to 2 weeks after initiation of glucocorticoids. Angiography is used to document and follow subcranial disease.

Management

Suspected GCA must be treated immediately to prevent visual loss. Prednisone, 1 mg/kg/d, is recommended. Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone for 3 days is used for acute visual loss, but established blindness is usually irreversible. Symptoms and inflammatory markers usually respond rapidly to glucocorticoids; lack of response should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis. High-dose prednisone is maintained for 2 to 4 weeks; after symptoms resolve and inflammatory markers normalize, prednisone is tapered by 10% to 20% every 2 weeks. Once a dose of 10 mg/d is reached, the taper is slowed to 1 mg per month. Patients should be carefully monitored for symptom recurrence. ESR and/or CRP should be monitored monthly but should not be the sole indication for adjusting the glucocorticoid dose. Mild flares can be managed with increases of prednisone by 10% to 20% and a slower tapering schedule.

Based on limited data, daily low-dose aspirin may help to reduce the risk of blindness and is recommended for those without contraindication. Glucocorticoid-sparing immunosuppressives such as methotrexate are sometimes used, although little data support their efficacy. The IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab was recently approved by the FDA for treatment of GCA.

The prognosis for properly treated GCA is good unless aortitis is present. GCA may recur.

All patients should undergo osteoporosis screening when starting steroids and yearly chest x-rays (up to ten years) to identify patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Although not a vasculitis, 1.polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is an inflammatory disorder that frequently accompanies 2.GCA.

PMR and GCA likely reflect the clinical spectrum of a single disease process, although PMR occurs 3 to 10 times more frequently. Up to 50% of patients presenting with GCA have PMR, and 20% of patients presenting with PMR have GCA symptoms on questioning.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

PMR is associated with pain and stiffness of the neck, shoulder, and hip girdle. Pain and stiffness are worse after immobility; 1 hour or more of morning stiffness is common. Inflammation is periarticular (bursitis and tenosynovitis). Synovitis in the hands and feet occasionally occurs. Constitutional symptoms and laboratory findings resemble GCA, but temporal artery biopsy should be performed only if GCA is suspected. Diagnosis of PMR is made clinically. Differential diagnosis includes myopathies, metabolic syndromes (thyroid and parathyroid), and musculoskeletal syndromes (capsulitis, cervical spondylosis, or calcium pyrophosphate deposition).

Management

PMR responds dramatically to low-dose prednisone (12.5-20 mg/d); lack of a rapid response should prompt consideration of alternate diagnoses. Prednisone taper is initiated 1 to 2 months after symptom resolution and requires months to years. Monitoring of recurrence is managed similarly to GCA. For relapses, recent guidelines for the management of PMR (developed by a collaborative effort of the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism) recommend increasing the prednisone to the last pre-relapse dose at which the patient was doing well, followed by a gradual reduction within 4 to 8 weeks back to the relapse dose. Glucocorticoid-sparing therapies are the same as for GCA. Prognosis is good, although periodic recurrences are common.

Takayasu Arteritis

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Takayasu arteritis (TA) causes inflammation of the large vessels, most commonly the aorta, followed by the subclavian, common carotid, and renal arteries; the pulmonary arteries may also be involved. TA is rare (40/million in Japan and 4.7 to 8/million elsewhere). In contrast to GCA, TA predominantly affects younger women. Arterial lesions are often stenotic (“pulseless disease”), and one third contain aneurysms. Histopathology is similar to GCA.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

TA manifestations include carotodynia, limb claudication, reduced pulses, bruits, and blood pressure discrepancies between the arms. Heart failure related to aortic insufficiency or coronary artery disease may occur. Neurologic manifestations include transient ischemic attack, stroke, and mesenteric ischemia. As with GCA, laboratory studies are nonspecific and reveal anemia as well as elevated ESR and CRP. Angiogram may demonstrate arterial stenosis or aneurysm (Figure 27).

Management

Primary treatment of TA is high-dose glucocorticoids (1 mg/kg/d) with a slow taper. Glucocorticoid-sparing medications such as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are used but without clear evidence for efficacy. Angioplasty, graft placement, and bypass may be necessary but should be avoided during active inflammation. The leading cause of death is heart failure; stroke and cardiovascular disease also contribute to morbidity. The 10-year survival rate is 90%.

Medium-Vessel Vasculitis

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a rare systemic necrotizing vasculitis that affects medium and occasionally small arteries. Prevalence is 31/million but declining. PAN is more common in men than women. Average age of onset is 50 years.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has been strongly associated with PAN. However, the proportion of patients with HBV-associated PAN has declined from 36% to less than 5% since the advent of the HBV vaccine; thus, most contemporary cases are presumed autoimmune. Activated endothelial cells as well as increased interleukins, T cells, and macrophages have been identified as potential contributors to vessel damage.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

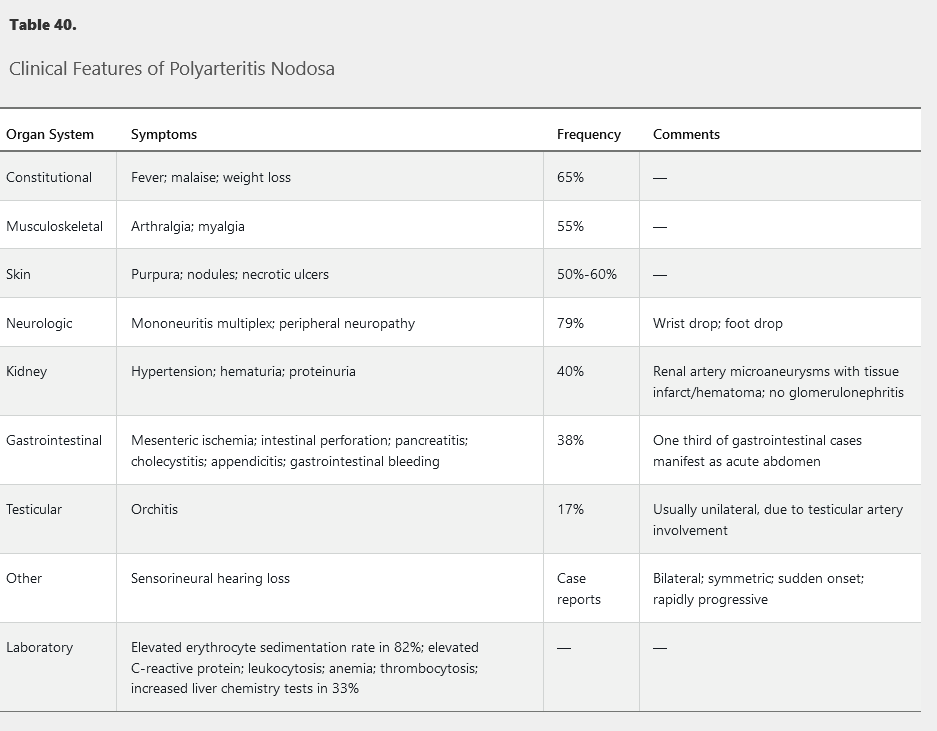

PAN most commonly affects the skin, neurologic, and musculoskeletal systems. It does not involve the lungs and rarely the heart. Kidney involvement is renovascular rather than glomerular. Cutaneous PAN is a variant confined to the skin. See Table 40 for the clinical and laboratory findings of PAN.

This entity may occur in the setting of chronic hepatitis B virus infection, HIV infection, and hairy cell leukemia. The most common symptoms are constitutional, including fever, malaise, and weight loss, and neurologic symptoms such as mononeuritis multiplex. Skin rashes, including purpura and necrotic ulcers, occur in more than half of patients. Kidney involvement manifests as hypertension due to renal artery vasculitis with renal infarction, not glomerulonephritis. Orchitis, an uncommon manifestation, is usually unilateral and due to testicular artery involvement. Mesenteric vasculitis may cause abdominal pain, perforation, and bleeding.

50 year old male with weight loss, foot weakness/numbness, testicular pain, leg rash, HTN

The gold standard for diagnosis is focal segmental panmural necrotizing inflammation of a medium-sized vessel shown on biopsy. The biopsy is usually performed on an involved, easily accessible area, such as skin or a peripheral nerve/muscle. PAN may also be diagnosed on angiogram; mesenteric or renal arteries show characteristic aneurysms and stenosis, especially at branch points.

Management

Glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide are indicated for severe organ-threatening disease; glucocorticoids and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are used for milder disease. HBV-associated PAN is treated with short-term glucocorticoids, antiviral medication, and plasmapheresis if necessary. The 5-year survival rate for treated PAN is 80%, and the relapse rate is 10% to 20%.

Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is a rare medium-vessel vasculitis of unknown cause that is confined to the central nervous system. Incidence is 2.4/100,000. Median age at onset is 50 years. There are three histologic presentations, all with patchy distribution: granulomatous (58%), lymphocytic (28%), and necrotizing (14%).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Patients with PACNS usually present with gradual and progressive symptoms of headache, cognitive impairment, neurologic deficits, transient ischemic attacks, and strokes. Laboratory studies are normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is abnormal in 90%, with elevated protein, lymphocytic pleocytosis, and occasional oligoclonal bands. MRI shows nonspecific white and gray matter changes and infarcts. MR angiography and CT angiography have limited usefulness due to poor resolution. Cerebral angiogram may demonstrate vessel “beading” (alternating dilations and stenoses) but has limited sensitivity and specificity. Brain biopsy is the best test for diagnosis, but the patchy distribution of findings results in a 50% false-negative rate.

Evaluation centers on ruling out other conditions, including infection, malignancy, and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome.

Management

PACNS is treated with high-dose glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide. Patients often have permanent disability from neurologic damage, and the recurrence rate is 27%.

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease (KD) is a medium-vessel vasculitis that affects children and is very rare in adults. KD presents as fever, rash, cervical lymphadenopathy, conjunctival congestion, and mucositis. Coronary vessel vasculitis, aneurysm formation, and other cardiac complications (heart failure, pericarditis, arrhythmias) may develop. Treatment is with intravenous immunoglobulin and aspirin.

Many patients recover fully. However, coronary aneurysms may develop, and adults who had KD in childhood may suffer long-term cardiac sequelae. Chronic low-dose aspirin is indicated for coronary artery abnormalities. Clopidogrel may be added for cases with multiple aneurisms; warfarin prophylaxis is recommended for giant aneurysms.

Small-Vessel Vasculitis

ANCA-Associated Vasculitis

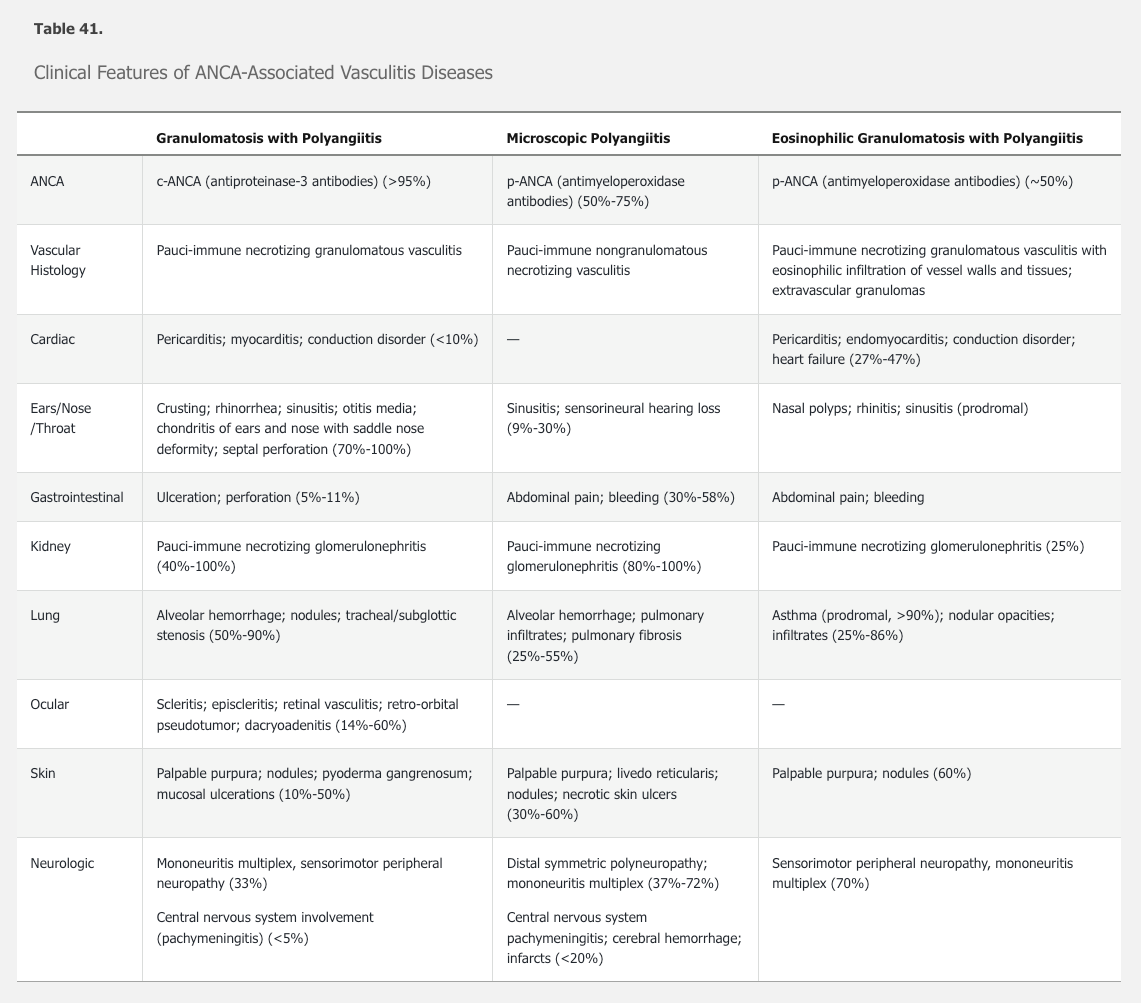

ANCA-associated vasculitis includes three diseases characterized by the presence of ANCA: granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, along with ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis.

There are two types of vasculitis-associated ANCA: p-ANCA (perinuclear, directed against the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase) and c-ANCA (cytoplasmic, directed against the neutrophil proteinase 3). Perinuclear and cytoplasmic refer to patterns of immunofluorescent staining; enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays are used to confirm antibody positivity.

ANCA may play a direct role in vessel damage by hyperactivating already primed neutrophils, leading to vessel endothelial inflammation and damage. The presence of granulomatous inflammation in some forms of ANCA-associated vasculitis suggests a role for cell-mediated immunity.

See Table 41 for a comparison of the features of the three forms of ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is the most common ANCA-associated vasculitis, with an incidence of 7 to 12/million/year. It is more prevalent in Nordic countries and White persons. Typical age of onset is between 45 and 60 years.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

GPA affects the upper and lower airways, kidneys, eyes, and ears. At least 50% of patients have constitutional symptoms. More than 95% of patients are ANCA positive, overwhelmingly (>90%) directed against proteinase 3 (anti-PR3 antibodies; c-ANCA).

GPA has two forms: systemic and localized. Systemic is more common, involves major organs, and is anti-PR3 positive. Localized has more granulomatous inflammation, has less vasculitis, and is less likely to be anti-PR3 positive. Patients in the localized group are more likely to be younger and female; have mainly ear, nose, and throat involvement; and be more prone to relapse.

The entire triad (upper airway disease, lower respiratory tract disease, and glomerulonephritis) may not be present initially. Upper respiratory tract symptoms include epistaxis, sinusitis, otitis media, and hoarseness. The associated granulomatous inflammation can lead to oral ulcers (as seen in this patient), nasal septal perforation, saddle nose deformity, and tracheal stenosis. Lung involvement may lead to pulmonary nodules, cavitary defects, infiltrates, or pleural effusion. Renal involvement occurs in approximately 70% of patients and is characterized by rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, fever, and weight loss are common. Ocular involvement also occurs frequently.

In the setting of a classic clinical presentation and positive c-ANCA/anti-PR3, diagnosis of GPA is straightforward. However, because of significant risks of treatment, biopsy of involved tissue is usually recommended. Histopathology of most tissues demonstrates pauci-immune necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis; pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis without granulomas is seen on kidney biopsy.

Anti–glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease (also known as Goodpasture disease) presents with hemoptysis and glomerulonephritis; however, a markedly elevated sedimentation rate is unusual. Constitutional symptoms (eg, malaise, weight loss, fever, arthralgia) are not typically present, and their presence is more suggestive of vasculitis. In addition, chest x-ray in anti-GBM disease reveals patchy basilar infiltrates, not the cavitation seen in this patient.

Management

For induction of remission in severe organ-threatening or life-threatening disease, treatment of GPA consists of high-dose glucocorticoids plus cyclophosphamide or rituximab, followed by maintenance therapy with azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or rituximab for at least 12 to 24 months after stable remission has been achieved. Glucocorticoids alone are insufficient to control GPA. Patients with nonsevere forms of GPA (such as arthropathy or upper airway disease) without organ-threatening disease can be treated with glucocorticoids plus either methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil; such patients should be carefully monitored for treatment failure or the development of renal or other organ-threatening disease, necessitating the more aggressive regimen. Using these approaches, GPA mortality has declined from 90% to around 10%.

The RAVE (Rituximab versus Cyclophosphamide for ANCA-Associated Vasculitis) trial demonstrated that rituximab is superior to cyclophosphamide in the subgroup of patients with relapse. In this study, remission without prednisone at 6 months was observed in 67% of rituximab-treated patients compared with 42% of cyclophosphamide patients (P = 0.01; NNT = 4). Rituximab was also as effective as cyclophosphamide in the treatment of patients with kidney disease or alveolar hemorrhage. There were no significant differences between the treatment groups with respect to rates of adverse events.

In trials of etanercept treatment for GPA, patients manifested an increased risk for the development of solid malignancies, especially if they had previously been treated with cytotoxic drugs. Therefore, etanercept is not considered first-line treatment for GPA.

Methotrexate is inadequate as induction therapy for severe disease; it can be used alone either as maintenance therapy after induction, or for mild and limited disease.

Relapses are common (>50% 5 years after initial remission) and may respond better to rituximab than to cyclophosphamide.

Kidney failure and infection are the main causes of mortality.

Microscopic Polyangiitis

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

The incidence of microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) is estimated at 2.7 to 94/million/year in Europe and lower elsewhere. Average age at onset is between 50 to 60 years with a predilection of men over women (1.8:1). In contrast to GPA, ANCA are less prevalent (50%-75%) and tends to be directed against myeloperoxidase (MPO) rather than PR3.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Like GPA, MPA characteristically affects the lungs and kidneys, along with other organ systems. See Table 41 for the clinical features of MPA. Diagnosis is suspected based upon typical clinical findings and positive ANCA, although negative ANCA does not rule out the diagnosis. The diagnostic gold standard is a biopsy demonstrating nongranulomatous necrotizing pauci-immune vasculitis of small vessels or pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis in the kidney. Absence of granulomas distinguishes MPA from GPA.

Management

Like GPA, MPA treatment requires high-dose glucocorticoids plus either cyclophosphamide or rituximab, followed by maintenance therapy with azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or rituximab.

Prognosis is worse in the setting of pulmonary hemorrhage or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Survival with treatment is 82% at 1 year and 76% at 5 years.

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is the rarest ANCA-associated vasculitis, with an incidence of 0.11 to 2.66/million/year and a prevalence of 10 to 14/million (France). EGPA has no predisposition for gender or ethnicity. In addition to neutrophil activation, eosinophil infiltration, activation, and degranulation participate in the pathogenesis.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The typical patient with EGPA has a history of asthma (96%-100%), nasal polyps, rhinitis, sinusitis, and/or atopy. A prodromal phase (months to years) consisting of arthralgia, myalgia, malaise, fever, and weight loss may occur. An eosinophilic phase with increased peripheral and tissue eosinophilia follows, with migratory pulmonary infiltrates and, less commonly, endomyocardial infiltration and gastrointestinal disease. The subsequent acute vasculitic phase includes mononeuritis multiplex or peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy (70%), kidney (25%), and skin involvement (60%). Paradoxically, the vasculitis phase is often associated with improvement of asthma. See Table 41 for the clinical features of EGPA.

Laboratory findings show peripheral eosinophilia of more than 10%, or more than 1500/µL (1.5 × 109/L). Only 50% of patients have a positive ANCA, mostly directed against MPO.

Diagnosis is based upon typical clinical findings, eosinophilia, and biopsy demonstrating fibrinoid necrosis and eosinophilic infiltration of vessel walls, as well as extravascular granuloma formation.

Management

In EGPA, glucocorticoids alone may be sufficient for mild disease without major organ involvement. With kidney, gastrointestinal, cardiac, or neurologic involvement, cyclophosphamide is indicated.

Mortality for EGPA is the lowest of all the forms of ANCA-associated vasculitis. The 5-year survival is 97%, and the relapse rate is 28%.

Immune Complex–Mediated Vasculitis

Immune complexes form from cross-linking of multiple antigens and antibodies. If not cleared, immune complexes deposit in tissue, leading to complement and neutrophil activation with inflammation and tissue damage. Although any tissue or organ may be affected, the classic finding is invariably in the skin. Inflammation and erythrocyte extravasation from involved vessels result in nonblanching palpable purpura, usually in dependent areas (Figure 28). Leukocytoclastic vasculitis refers to disintegration of nuclei (nuclear dust) of dead neutrophils along with fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall.

Cryoglobulinemic Vasculitis

Cryoglobulins can cause immune complex–mediated small-vessel vasculitis. There are three types of cryoglobulins; discussion here is limited to types II and III (“mixed” types). Both are polyclonal, but type II cryoglobulins include a monoclonal IgM rheumatoid factor, whereas type III cryoglobulins include a polyclonal IgM rheumatoid factor. The ability of rheumatoid factor to directly bind other antibodies facilitates the formation of immune complexes even in the absence of persistent antigen. See MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology for details on cryoglobulins and the differentiation from cold agglutinin disease.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Mixed cryoglobulinemia accounts for 85% to 90% of all cases; 90% of mixed cases are related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, which can cause both type II and type III cryoglobulinemia. Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren syndrome cause type III cryoglobulinemia. Onset is usually in the fifth decade, and women slightly outnumber men.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Cutaneous symptoms (palpable purpura, Raynaud phenomenon, ulcers, necrosis, and livedo reticularis) predominate in 70% to 90% of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia, but any organ may be involved. Peripheral neuropathy (60%), arthritis (40%), and glomerulonephritis (40%) are common. In addition to cryoglobulins, a low C4 complement and positive rheumatoid factor are present. A false-negative cryoglobulin result may occur if the serum sample is not maintained at 37.0 °C (98.6 °F) due to ex vivo cryoprecipitation at room temperature.

HCV infection associated with mixed cryoglobulinemia may go unrecognized for many years before the development of vasculitis. It is therefore important to test for HCV infection in patients with cryoglobulinemia.

Management

When possible, treatment of the underlying cause of cryoglobulinemia is the first priority. For HCV-related disease, antiviral medication is the primary therapy. For severe or refractory disease, the vasculitis must be independently addressed. Glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide have been used in the past; plasmapheresis and rituximab (provided there is no hepatitis B virus infection) have demonstrated efficacy and may carry less toxicity.

IgA Vasculitis

See MKSAP 18 Nephrology for information on IgA nephropathy and on kidney involvement in IgA vasculitis.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura) is a common vasculitis of childhood that occurs rarely in adults. Estimated incidence in adults is 14/million/year. Onset is often preceded by a viral or streptococcal upper respiratory infection.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Patients with IgA vasculitis typically present with a palpable purpura in dependent areas. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain or bleeding (65%), arthritis and arthralgia (63%), and glomerulonephritis (40%) may be present. Although rare, life-threatening pulmonary hemorrhage may occur.

Triad: abdominal pain, arthralgia, purpura

There are no specific laboratory tests for diagnosis; serum IgA may be elevated but is not sensitive or specific. Diagnosis is confirmed with biopsy. Skin biopsy demonstrates leukocytoclastic vasculitis with heavy deposits of IgA and complement on immunofluorescent staining. Renal histology is identical to IgA nephropathy.

Management

Although IgA vasculitis in children tends to be self-limited, adults are more likely to develop severe persistent disease, especially nephropathy, and may require glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide.

Hypersensitivity Vasculitis

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Hypersensitivity vasculitis is a small-vessel vasculitis mediated by immune complex deposition confined to the skin. It may be triggered by an antigen such as a drug or infection; in 50% of cases, the antigen is unknown.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The most common presentation of hypersensitivity vasculitis is palpable purpura in dependent regions, developing 7 to 10 days after exposure to a triggering antigen; lesions appear in “crops” and resolve over a few weeks after the antigen is removed. Internal organs are unaffected. Skin biopsy with immunofluorescence demonstrates leukocytoclastic vasculitis without heavy IgA deposits. Evaluation should be guided by clinical signs and symptoms, and may only require a complete blood count, basic chemistries, and urinalysis.

Management

Removal of the antigen (if identified) and supportive care are usually sufficient. Resolution within a month is the rule. If symptoms persist or recur, anti-inflammatories, topical or low-dose systemic glucocorticoids, colchicine, or dapsone may be helpful.