Systemic Sclerosis

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multiorgan disease characterized by fibrosis and vasculopathy. The skin is the principal target, but internal organs are also affected. SSc is relatively rare, with a prevalence of 275 cases per million, and an annual incidence of 19 cases per million. It is more common among women and Black persons.

Vascular injury, vascular and visceral fibrosis, and innate and adaptive immune activation with autoantibody production play an interactive role in SSc. One of the earliest SSc manifestations is Raynaud phenomenon, suggesting that vascular injury precedes the fibrotic reaction. With vascular damage, the endothelial cells release endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor that also induces vascular smooth muscle proliferation and fibroblast activation. Platelet activation occurs concurrently with subsequent release of growth factors that promote further vasoconstriction, fibroblast activation, and collagen production.

B-cell activation results in production of interleukin (IL)-6, which directly stimulates fibroblasts as well as various autoantibodies. The end result is increased collagen production and deposition by activated scleroderma fibroblasts, along with a progressive obliterative vasculopathy.

Classification

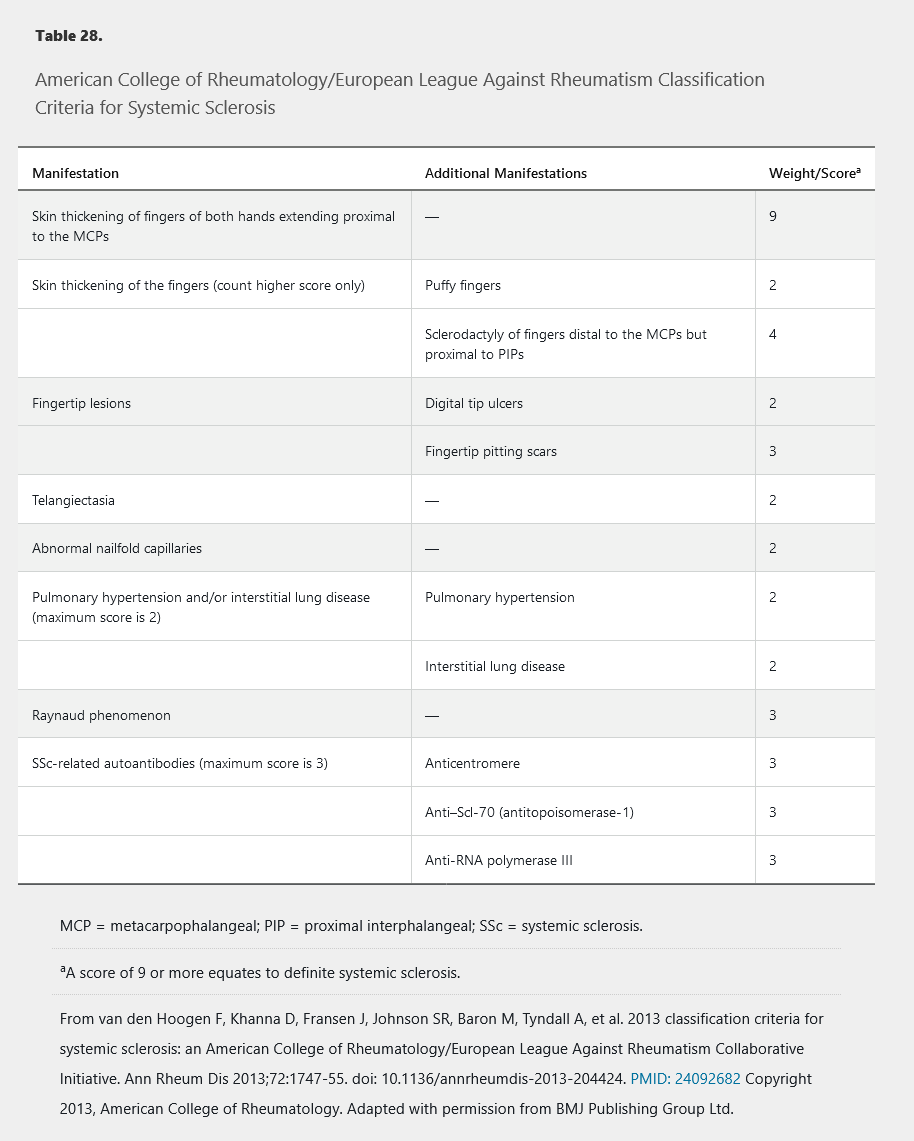

Although intended for research studies, the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism SSc classification criteria can be useful when a patient presents with features suggesting SSc (Table 28).

Classically, SSc is divided into three subtypes based on the extent of skin involvement: limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (LcSSc), diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (DcSSc), and systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (internal organ involvement only). These subtypes have clinical and prognostic utility because specific long-term complications may be more likely in one subtype than another; however, overlap is common. Importantly, LcSSc is less commonly accompanied by fibrosis of internal organs, but is most commonly associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension and CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) syndrome.

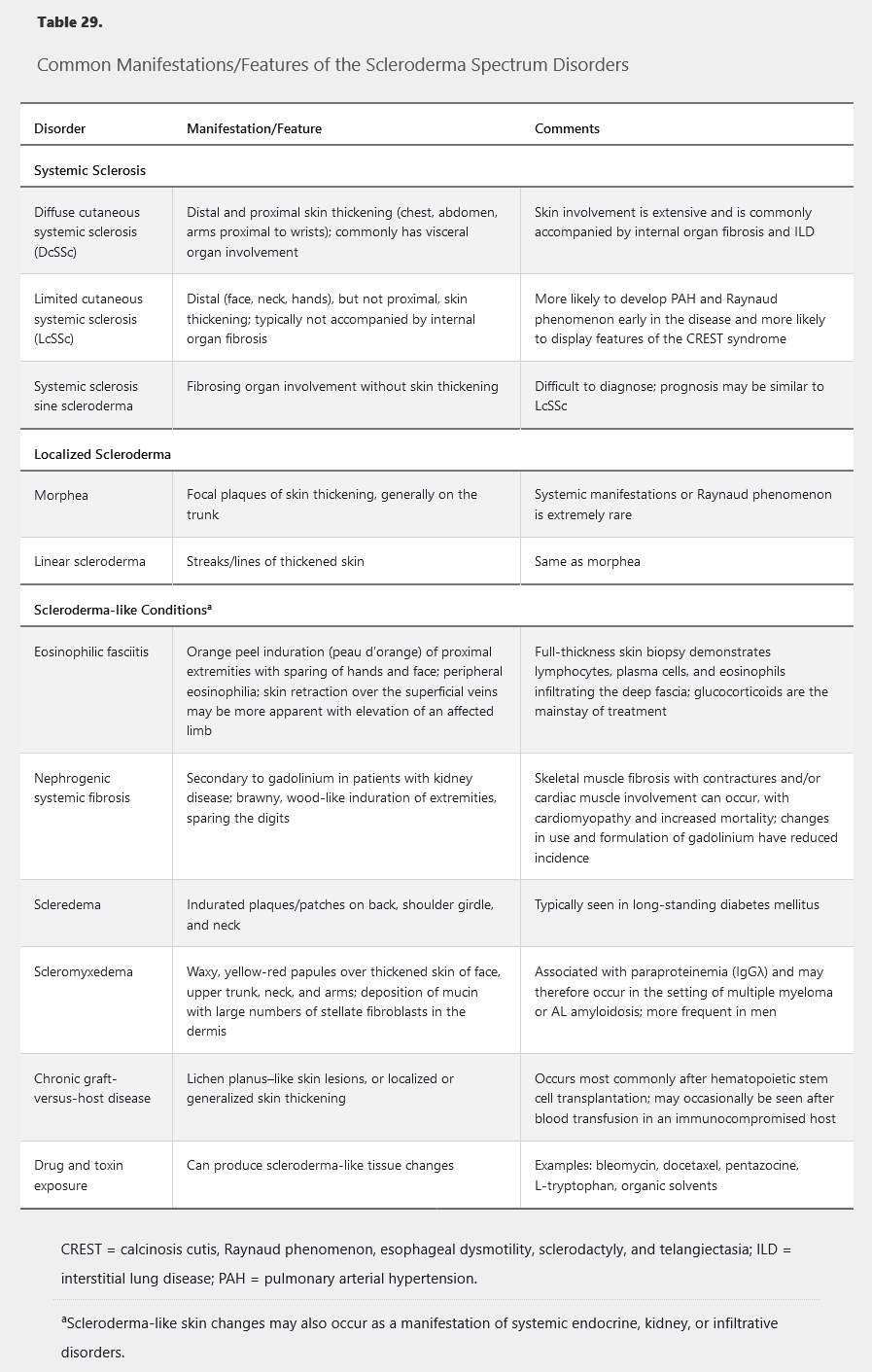

Various disorders may present with skin thickening and other manifestations that overlap with the findings of SSc; these conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis of SSc (Table 29). Importantly, these conditions are not typically associated with Raynaud phenomenon, and the absence of Raynaud phenomenon in a patient with skin thickening makes SSc unlikely.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

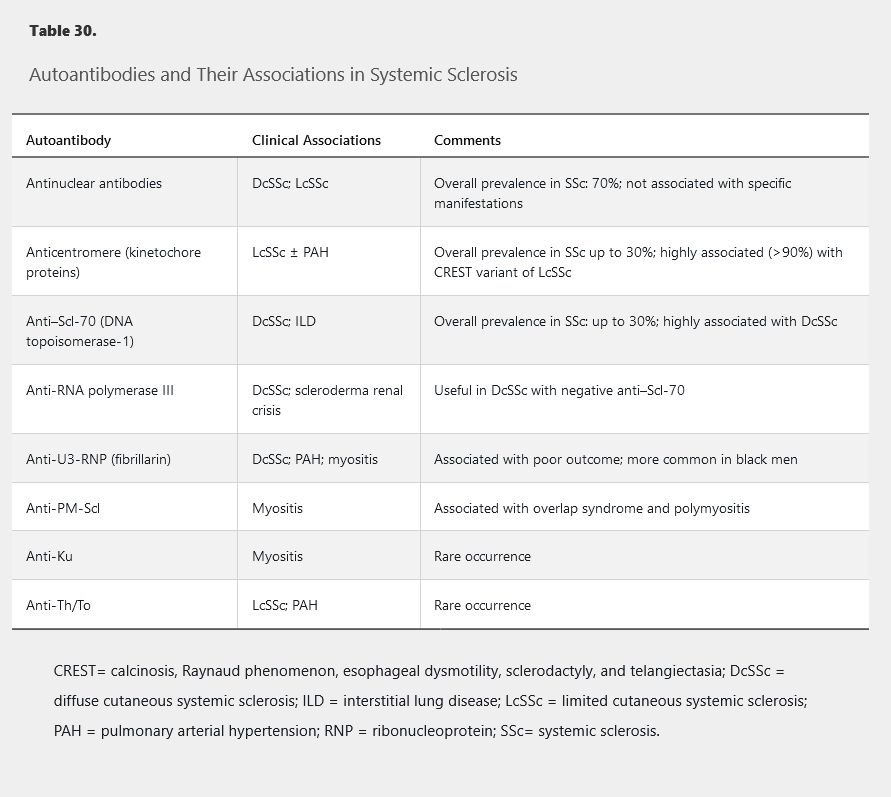

The diagnosis of SSc is dependent on the presence of specific clinical findings and autoantibodies (present in 90%-95% of patients). In patients with clinical features suggestive of SSc, autoantibody testing should be done (Table 30).

This patient's presentation is consistent with CREST syndrome, a variant of the limited cutaneous form. These patients are anti-centromere antibody positive and carry a more favorable prognosis (in comparison to DcSS). They do not develop renal failure or the cardiac disease that can be seen with DcSS (Choices A & B); however, they are more prone to developing pulmonary hypertension, often without interstitial fibrosis. In contrast, patients with DcSS may develop severe forms of interstitial lung disease.

Cutaneous Involvement

The skin is the most common organ involved in SSc, with the hands being universally affected. In LcSSc, the skin over the fingers/hands, face, and neck is typically affected. In DcSSc, skin involvement is more extensive and additionally includes the arms, trunk, and lower extremities.

The earliest skin manifestations are often diffusely swollen fingers/hands (sclerodactyly). Skin thickening, especially in LcSSc, may be subtle, and the inability to tent the skin over the fingers may be an important clue. With time, the skin becomes thickened, atrophic, and immobile; skin thickening around the joints can lead to contractures (Figure 19).

A 35-year-old woman with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Note shortening of fingers and tight atrophic appearance of the skin. This patient is unable to make a full fist.

A 35-year-old woman with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Note shortening of fingers and tight atrophic appearance of the skin. This patient is unable to make a full fist.

Vascular complications of the skin include digital infarcts, subungual infections, and ischemic skin ulceration. Another feature is poikiloderma, in which areas of hyperpigmentation mixed with hypopigmentation give the skin a salt-and-pepper appearance.

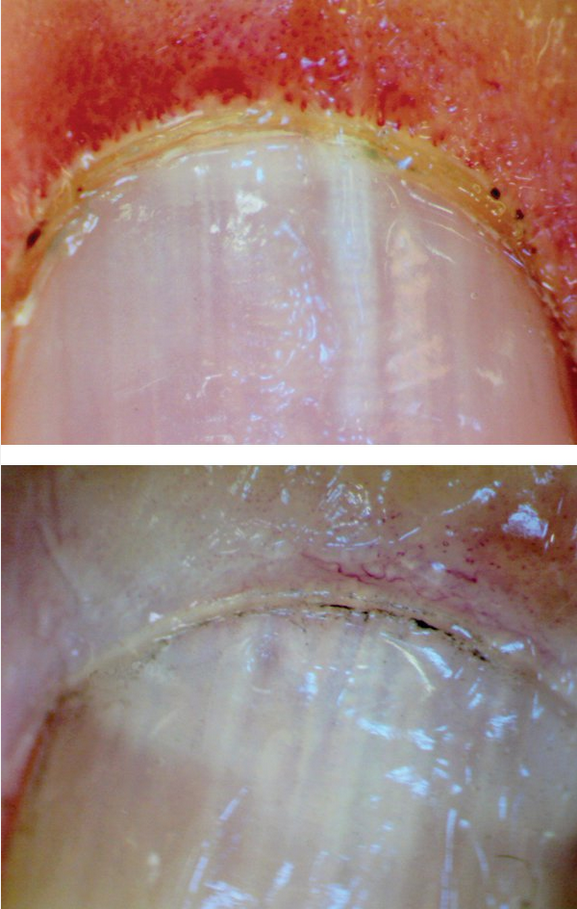

Raynaud phenomenon occurs in approximately 95% of patients with SSc; it is the most common early manifestation of SSc, typically occurring years before other changes. Initially, Raynaud phenomenon is episodic, but with vascular fibrosis, the blood supply becomes permanently restricted. Approximately 80% of patients with the combination of Raynaud phenomenon, an SSc-associated autoantibody, and nailfold capillary changes in an SSc pattern (Figure 22), will develop SSc.

Capillary loops in systemic sclerosis. Top, Early changes with loss of capillary loop density (or drop out) with marked dilatation of the remaining capillary loops. Bottom, Late changes with extensive loss of capillary loops.

Capillary loops in systemic sclerosis. Top, Early changes with loss of capillary loop density (or drop out) with marked dilatation of the remaining capillary loops. Bottom, Late changes with extensive loss of capillary loops.

Digital ulcers occur in about 15% of patients with SSc, typically on the extensor surfaces and tips of the fingers and toes but also on the dorsum of hands and feet and even on the lower extremities. Vascular changes in the extremities may be indicative of involvement of the microcirculation of internal organs.

Facial involvement can lead to limitation of the oral aperture and difficulty eating. The face is also typically devoid of wrinkles, causing patients to sometimes look younger than their age.

Calcinosis occurs in approximately 25% of patients with SSc (Figure 20). Present in the hands, forearms, elbows, gluteal region, and iliac crest, these deposits can be seen/felt and are easily detected on radiograph.

Calcinosis seen in CREST (calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) syndrome in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis. This patient has deposits of calcium in the subcutaneous tissues around the elbow. Calcinosis often occurs in the hands and forearms but can also affect other locations such as the trunk or lower extremities.

Calcinosis seen in CREST (calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) syndrome in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis. This patient has deposits of calcium in the subcutaneous tissues around the elbow. Calcinosis often occurs in the hands and forearms but can also affect other locations such as the trunk or lower extremities.

Musculoskeletal Involvement

Joint involvement occurs in 12% to 65% of patients with SSc; it has a hand/wrist predominance and is one of the few forms of inflammatory arthritis that affects the distal interphalangeal joints. Between 1% and 5% of patients have a rheumatoid arthritis–SSc overlap, with positive anti–cyclic citrullinated antibodies and classic rheumatoid arthritis manifestations along with those of SSc.

Patients with SSc may develop acro-osteolysis, or resorption of the terminal bony tuft of fingers and less commonly the toes, with prevalence as high as 20% to 25% in more severe disease (Figure 21).

A posteroanterior radiograph of the hands in a patient with systemic sclerosis and acro-osteolysis. Note the destruction of the distal phalanges, particularly of the first and second digits, which will eventually result in clinical shortening of the affected digits.

A posteroanterior radiograph of the hands in a patient with systemic sclerosis and acro-osteolysis. Note the destruction of the distal phalanges, particularly of the first and second digits, which will eventually result in clinical shortening of the affected digits.

SSc-associated myositis occurs in 10% to 15% of patients. Myalgia and proximal muscle weakness are common symptoms. Serum creatine kinase and/or serum aldolase levels are elevated, and electromyogram demonstrates myopathic changes. There is a strong association between SSc-associated myositis and myocardial involvement. The presence of anti-PM-Scl antibodies identifies a group of patients with an overlap between polymyositis and SSc. These patients usually have less skin and gastrointestinal involvement, but have more calcinosis and lung disease.

Tendon rubs can be felt or heard with a stethoscope because fibrosis affects tendons/tendons sheaths, leading to palpable and audible friction.

Gastrointestinal Involvement

Symptoms of esophageal dysmotility and reflux are common in all forms of SSc and may offer an early clue to the diagnosis when associated with other symptoms.

Approximately 80% of patients with SSc have involvement of the lower two thirds (smooth muscle portion) of the esophagus. Manifesting primarily as symptoms of dysmotility and/or gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal involvement is also associated with an increased risk of Barrett esophagus and adenocarcinoma.

Gastric symptoms also result mainly from dysmotility. Patients describe early satiety and may report nausea and vomiting as a result of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), also known as watermelon stomach, is most common in patients with DcSSc and those with anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. GAVE is the proliferation of blood vessels typically in the antrum of the stomach; on endoscopy, it has the appearance of watermelon stripes (watermelon stomach). Approximately 60% of patients with GAVE have an underlying autoimmune disease; the remainder have portal hypertension secondary to hepatic cirrhosis. GAVE can be a source of both acute and chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. First-line therapy is argon plasma coagulation or laser coagulation. Bleeding ectasias can occasionally cause significant blood loss.

Small intestine bacterial overgrowth is common and can cause malabsorption and diarrhea. Diagnosis is established by hydrogen breath test, although an empiric trial of antibiotics is often utilized. Small intestine dysmotility can result in pseudo-obstruction. Large intestine dysmotility may lead to constipation, and vascular ectasia can occur in the large intestine (watermelon colon). Some patients may develop fecal incontinence.

More than 70% of patients with SSc have clinical gastrointestinal involvement. Gastrointestinal motility is compromised in 40% to 90% of patients with systemic sclerosis, especially those with diffuse disease. Because of the decrease in motility of the small bowel, bacterial overgrowth occurs and leads to symptoms including diarrhea, bloating, and pain, and can lead to malabsorption. Patients with SSc can also develop chronic pancreatic insufficiency and develop symptoms similar to SIBO, which must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Diagnosis of SIBO can be confirmed with glucose hydrogen breath testing or jejunal aspirate cultures. Treatment is with rotating antibiotics to try to reduce the overgrowth using agents with both aerobic and anaerobic coverage. Probiotics may have some benefit in such patients. It is important to screen such patients for nutritional deficiencies.

Kidney Involvement

One of the most concerning manifestations of SSc is scleroderma renal crisis, which affects 5% of patients and was previously the chief cause of mortality. Risk factors include DcSSc, use of moderate- to high-dose glucocorticoids, and the presence of anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. Patients characteristically present with manifestations of hypertensive emergency, including headache, encephalopathy, seizures, and hypertensive retinopathy. Rarely, a normotensive form of scleroderma renal crisis can occur.

Laboratory tests demonstrate microangiopathic hemolytic anemia with schistocytes on peripheral smear, thrombocytopenia, and proteinuria. Serum creatinine is typically elevated and may remain so for some time after controlling blood pressure. Abnormalities in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and endothelin-1 contribute to the pathophysiology. ACE inhibitors significantly improve kidney survival and decrease mortality among patients with SRC, regardless of the serum creatinine level.

Lung Involvement

Lung involvement in SSc includes pleuritis and pleural effusions, interstitial lung disease (ILD), pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), bronchiolitis, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, respiratory muscle weakness, and skin involvement of the trunk restricting chest wall movement. Patients are also at increased risk of lung cancer.

Significant ILD occurs in 50% of patients with DcSSc (85% of patients with anti–Scl-70 antibodies) and 35% of patients with LcSSc, and is the main cause of disease-associated mortality. The most common pathology pattern is nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis followed by usual interstitial pneumonitis. In patients with SSc, men are more likely than women to develop ILD, and Black persons tend to have more severe disease. An abnormal FVC early in the disease course (first 5 years) is highly predictive of developing more severe disease, as is fibrosis of more than 20% of lung volume on baseline high-resolution CT scan. There is a strong association between ILD and GERD, but whether GERD contributes to ILD (through aspiration) is uncertain. ILD is common enough that all patients should undergo pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and high-resolution CT at the time of initial SSc diagnosis, and PFTs with DLCO should be repeated every 6 to 12 months for 5 years. A decline in the FVC of 10% or the DLCO of 15% within 12 months should raise concern for progression.

PAH has a prevalence of 10% in SSc. Patients present with exertional dyspnea, and with more advanced disease may have chest pain and edema as the right ventricle begins to fail. Pulmonary vascular disease occurs in up to 40% of patients with systemic sclerosis. Vascular disease leading to pulmonary arterial hypertension may occur secondary to interstitial lung disease (typically in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis) or as an isolated process (typically in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Patients are usually asymptomatic in early disease but later develop dyspnea on exertion and diminished exercise tolerance. Severe disease can lead to right-sided heart failure. This patient with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and progressive dyspnea has a normal chest radiograph and a normal pulmonary examination, but an increased pulmonic sound and a widened split of S2 on cardiac examination compatible with pulmonary hypertension. Taken together, the most likely cause of the patient's progressive dyspnea is pulmonary arterial hypertension. Initial evaluation of this patient should proceed with pulmonary function tests and echocardiography. Patients with SSc should undergo echocardiography annually and more frequently for new or concerning symptoms. PFTs can provide a clue to underlying PAH; an FVC/DLCO ratio of ≥1.6 suggests the diagnosis. Right heart catheterization is required for accurate diagnosis.

Cardiac Involvement

Cardiac involvement with SSc is more common in men. Clinically significant pericarditis occurs in 10% of patients. Myocardial fibrosis is a more significant process caused by vascular vasospasm leading to myocardial ischemia and fibrosis. The result may be heart failure and arrhythmias. Mortality in those with myocardial fibrosis is quite high.

Management

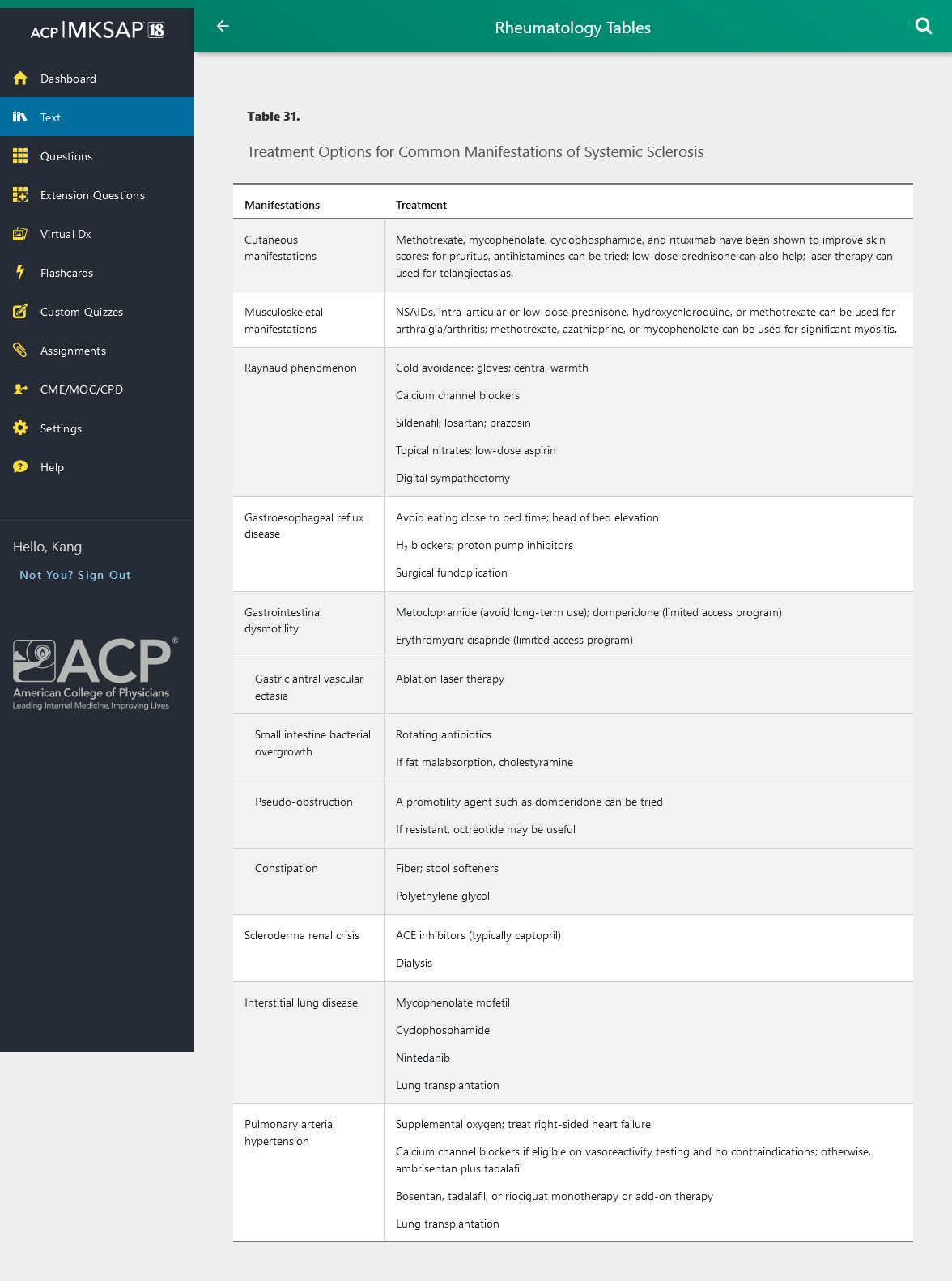

Table 31 outlines treatment options for manifestations of SSc.

ACE inhibitors (typically captopril) can be lifesaving in patients with scleroderma renal crisis and should be titrated to control blood pressure. Dialysis may be needed temporarily. ACE inhibitor therapy should be continued in scleroderma renal crisis even in the presence of a rising serum creatinine and the need for dialysis, as late improvement may occur. In patients at high risk for developing scleroderma renal crisis, the prophylactic use of calcium channel blockers seems to offer some protection. However, prophylactic use of an ACE inhibitor has not been shown to offer protection and may increase mortality.

Cyclophosphamide can be used for stabilizing ILD, but the impact is modest and may not persist beyond 1 year. Recent evidence suggests that mycophenolate mofetil is as useful for stabilizing ILD as cyclophosphamide in SSc but with less toxicity. Mycophenolate mofetil can also be used for long-term therapy, making it the preferred agent for most patients with SSc-associated ILD.

Rituximab is a promising agent in SSc; in case series and one controlled trial, it has stabilized or slightly improved lung function and skin ulcers. In a 2019 randomized controlled trial, the annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity was lower with nintedanib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) than with placebo among patients with ILD associated with systemic sclerosis. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been studied for several years in patients with severe SSc; one third to one half of patients had significant improvement in skin thickening and antibody status. However, cost and potential toxicity limit the utility of stem cell transplantation at present.

Pregnancy

Pregnant patients with SSc may experience hypertensive disease, preeclampsia, preterm delivery, and low birth weights. In general, pregnancy does not make SSc worse, and some features (for example, digital ulcers) may actually improve. Contraindications to pregnancy in patients with SSc include PAH and severe restrictive lung disease (FVC of <1 L); in the setting of PAH, the hemodynamic changes of pregnancy can put the mother at considerable risk. See Principles of Therapeutics for details on medications and pregnancy.