Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

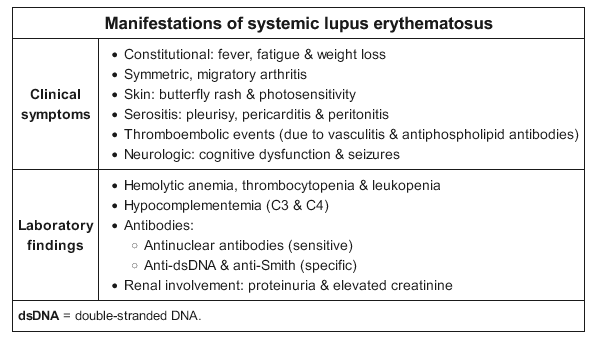

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disease characterized by a heterogeneous constellation of organ involvement and the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and other autoantibodies.

In SLE, a complex and varying interaction of genes, environment, and random events leads to a breakdown of self-tolerance and autoimmunity. Defects in cellular apoptosis result in inadequate clearance of intracellular proteins, especially nuclear antigens, promoting the generation of self-directed T and B cells and the initiation/propagation of autoimmunity. Cytokine generation supports the autoreactivity, with type-1 interferons playing a major role. Autoantibodies may directly induce tissue damage or promote the formation of immune complexes that lead to complement activation and tissue inflammation and damage. Inheritance of SLE risk is polygenic, including major histocompatibility complex.

The risk of SLE developing in genetically predisposed individuals increases at puberty and peaks in the third decade. Approximately 90% of adult patients are women. The disease is more common, and perhaps more severe, in Black, Asian, and Hispanic ethnicities.

Clinical Manifestations

Mucocutaneous Involvement

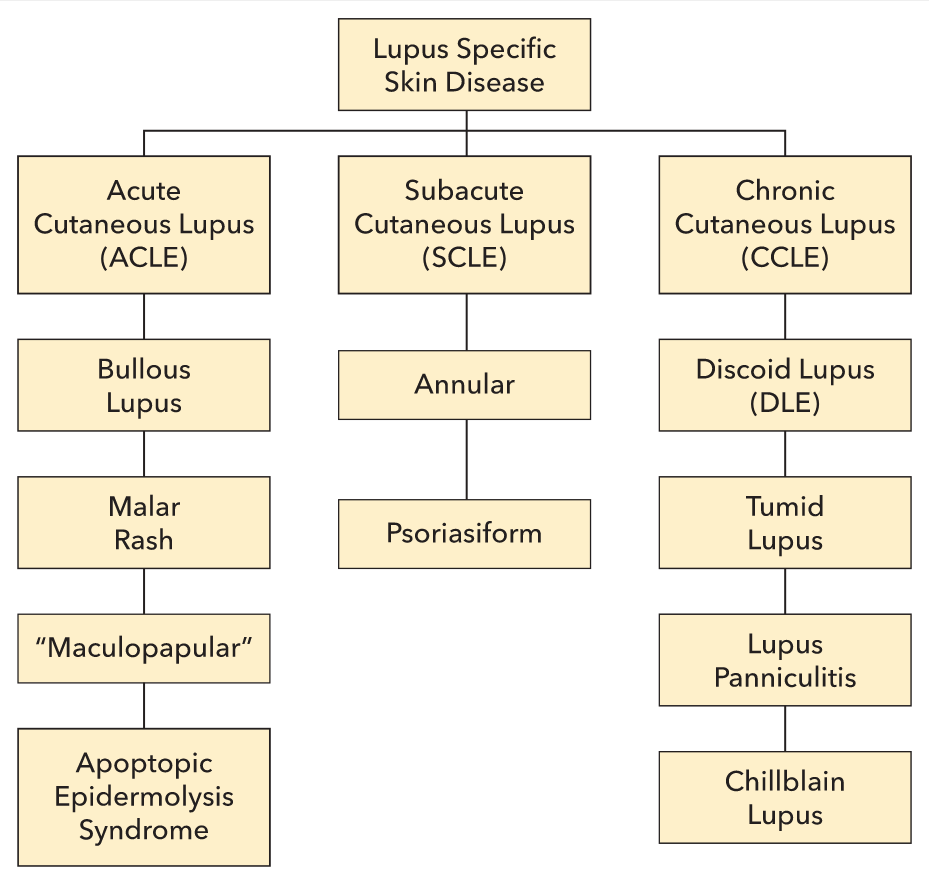

Lupus erythematosus (LE) is a family of autoimmune conditions featuring autoantibodies directed against nuclear targets. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) can exist with or without systemic disease; however, as many as 80% of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients have some degree of skin disease. CLE is divided into two broad categories: lupus-specific skin disease and lupus-nonspecific skin disease. Lupus-specific skin disease is further divided into three groups: acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE), subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) (Figure 98). The lupus-specific skin diseases are defined by their clinicopathologic characteristics and are not found in other conditions. Nonspecific skin disease may appear in other unrelated disorders.

Skin disease occurs in up to 90% patients with SLE and is classified as acute, subacute, or chronic.

Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE) presents as an erythematous, macular, patchy eruption, sometimes with desquamation. The facial eruption of ACLE (malar or butterfly rash) is characterized by erythema/edema over the cheeks and bridge of the nose, sparing the nasolabial folds; it occurs in about 50% of patients with SLE (Figure 15).

Less characteristically, ACLE can also involve the neck, upper chest, and dorsum of the arms and hands; it affects the skin between the fingers but spares the knuckle pads. In some patients, a bullous eruption can occur. ACLE usually responds to therapy and heals without scarring or atrophy.

ACLE can also manifest as a “maculopapular” variant that is photosensitive and distributed over the chest, upper back, and arms. Both rashes are pink-violet macules to scaly papules and plaques. In vibrant cases, severe inflammation can cause separation of the epidermis, which appears similar to Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrosis (SJS/TEN) and may involve oral ulcerations. This is sometimes referred to as apoptotic epidermolysis syndrome. Bullous lupus, a variant of ACLE, is a blistering disorder caused by antibodies to the anchoring fibrils of the epidermis. Essentially all patients with ACLE have SLE and as such tend to have systemic symptoms and positive serologies. The rash of ACLE does not scar.

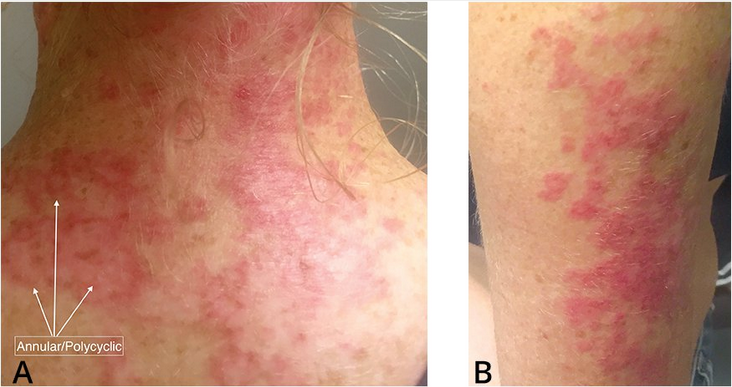

SCLE appears as one of two variants: annular and polycyclic photosensitive plaques on the back, chest, and extremities, or psoriasiform scaly plaques in a similar distribution (Figure 100). SCLE does not scar, but may resolve with temporary pigmentary changes. Fewer than one in four SCLE patients have SLE, and as many as one in three are drug induced (Table 20). The latter may resolve with withdrawal of the causative agent. Up to 70% of patients with SCLE have an elevated antinuclear antibody titer, with anti-Ro and anti-La being overrepresented. Unlike psoriasis, SCLE is photodistributed, tends to burn more than itch, and has a lighter pink-to-violet tone when compared with the red tones of psoriasis. Psoriasis improves with sun exposure, whereas SCLE worsens with sun exposure.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a photosensitive rash occurring especially on the arms, neck, and face (Figure 16). It consists of erythematous annular/polycyclic or patchy papulosquamous lesions, often with a fine scale, that may leave postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation. SCLE is associated with anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies (prevalence >75%) and can occur in isolation or as a manifestation of underlying SLE.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as pink nonscarring annual and polycyclic macules and plaques on the chest and neck.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as pink nonscarring annual and polycyclic macules and plaques on the chest and neck.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is characterized by erythematous, macular, or patchy skin lesions that are scaly and can evolve as (A) annular/polycyclic lesions or (B) papulosquamous plaques.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is characterized by erythematous, macular, or patchy skin lesions that are scaly and can evolve as (A) annular/polycyclic lesions or (B) papulosquamous plaques.

CCLE is another group of related skin diseases. Discoid lupus (DLE) is the most common. DLE lesions start as red-to-violet plaques that develop a hyperpigmented border and thick adherent scale in the center (Figure 101). Pulling back the scale will reveal projections from the underside that resemble carpet tacks. Eventually the centers of lesions become atrophic and depigmented, causing permanent alopecia if occurring in hair-bearing areas (Figure 102). Plaques favor the head and neck, particularly the scalp and conchal bowls (the hollow of the auricle of the external ear). CCLE in general has a low association with SLE, and DLE of the head and neck has approximately a 10% risk of underlying systemic disease.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is the most common chronic cutaneous manifestation of SLE, occurring in 20% of patients (Figure 17). DLE presents as hypo- or hyperpigmented patches or plaques, with erythema during active disease, which may be variably atrophic or hyperkeratotic. Unlike ACLE and SCLE, DLE can cause scarring, atrophy, and permanent alopecia. DLE also occurs as an isolated finding in the absence of SLE. Isolated DLE is usually limited to the neck, face, and scalp, whereas discoid lesions in SLE are more diffusely distributed. Patients with isolated DLE tend to be ANA negative and usually do not progress to SLE. It is important to differentiate isolated DLE from DLE as a manifestation of underlying SLE when making therapeutic and prognostic decisions.

Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus on the occiput, with hyperpigmented borders, depigmented centers, dilated empty follicular ostia.

Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus on the occiput, with hyperpigmented borders, depigmented centers, dilated empty follicular ostia.

Discoid lupus erythematosus. This patient has hyperpigmented, raised patches with keratotic scaling and follicular plugging involving the malar and perioral areas as well as the bridge of the nose. Areas of atrophic scarring are also present.

Discoid lupus erythematosus. This patient has hyperpigmented, raised patches with keratotic scaling and follicular plugging involving the malar and perioral areas as well as the bridge of the nose. Areas of atrophic scarring are also present.

Lupus panniculitis appears as painful red indurated subcutaneous plaques that eventually cause atrophy and scarring depressions of the skin. DLE can often be seen overlying lupus panniculitis. The condition typically appears on the cheeks, lateral arms, breasts, and buttocks. Rarely lupus panniculitis transforms to a form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Chilblains or pernio are tender purple papulovesicles or plaques that appear on toes and fingers (Figure 103). They are triggered by exposure to cold or moisture and are unrelated to Raynaud phenomenon. They respond well to warming and calcium channel blockers.

Chilblains/pernio in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus appearing as tender purple plaques on the toes.

Chilblains/pernio in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus appearing as tender purple plaques on the toes.

Tumid lupus presents with dermal macules or plaques on sun-exposed skin and is the most photosensitive of the lupus-specific skin diseases. It is uncommonly found in association with SLE (Figure 104).

Tumid lupus showing reticulate pink dermal plaques on the forehead in typical photodistribution.

Tumid lupus showing reticulate pink dermal plaques on the forehead in typical photodistribution.

Two lupus-nonspecific features are included in the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics criteria. First, oral or nasal ulcerations, a variant of minor aphthae, appear as white tender erosions of the oro- or nasopharynx. Second, “lupus hair,” which is a variant of nonscarring alopecia, is a form of telogen effluvium. It may be localized, patchy, or diffuse. Most typical is a recession of the frontal hairline with sparse, short, wiry, and broken hairs left behind. Hair regrowth can be a sign of disease control.

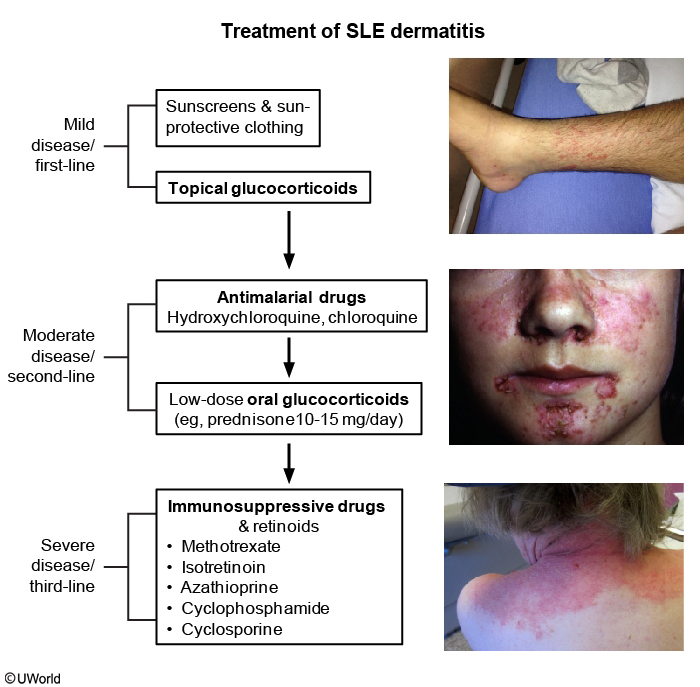

Therapy for cutaneous lupus includes antimalarial agents such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, dapsone, and combination therapy (Table 21). Thalidomide is effective for some patients with chronic cutaneous lupus.

The importance of photoprotection in the patient with lupus cannot be overstated. Patients should avoid peak sun hours and use barrier protection such as protective clothing and wide brim hats. Broad spectrum sunscreen (ultraviolet A and B filters) should be worn every day, with frequent reapplication. Sunlight and other sources of ultraviolet light drive disease activity, cause flares in stable patients, or even flare systemic disease.

Painless oral or nasopharyngeal ulcerations occur in 5% of patients with SLE, with involvement of hard palate suggestive of the diagnosis. Rarely, DLE can be associated with painful ulcers. Nonscarring alopecia is a common feature of active SLE, with hair regrowth a sign of disease control. Raynaud phenomenon occurs frequently, reflecting arterial vasospasm of digital arteries.

See MKSAP 18 Dermatology for more information.

Musculoskeletal Involvement

Joints are affected in 90% of patients with SLE. The most common involvement is polyarthralgia, with frank arthritis occurring in 40%. Typical distribution is small peripheral joints, but large joints are also affected. In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, SLE arthritis is nonerosive, but reducible subluxation of the digits, swan neck deformities, and ulnar deviation (Jaccoud arthropathy) can occur.

A serious complication of SLE is osteonecrosis, which most commonly affects the hips but can also involve other large joints, and should be suspected when there is otherwise unexplained pain and/or reduced range of motion. Chronic prednisone doses (>20 mg/d), severe/active SLE, and vasculitis are all associated with increased risk. MRI is the modality of choice for sensitive evaluation of early disease, with plain radiography useful to diagnose and follow later stages. Small lesions can improve and resolve spontaneously, but larger lesions usually lead to bony collapse and structural sequelae.

Plain radiography is the initial radiographic study of choice, although MRI is the gold standard for diagnosis and may be required if plain radiography is not diagnostic. Early radiographic findings include bone density changes, sclerosis, and, eventually, cyst formation. Subchondral radiolucency producing the “crescent sign” indicates subchondral collapse. End-stage disease is characterized by collapse of the femoral head, joint-space narrowing, and degenerative changes.

Myalgia and subjective weakness are common; frank myositis is rare. Assessment is complicated by the potential effect on muscle of antimalarials (rarely) and glucocorticoids (commonly), which must be differentiated from active SLE disease. Fibromyalgia is a common comorbidity (30%); symptoms may be similar to active SLE disease.

Kidney Involvement

Kidney disease occurs frequently among patients with SLE (70%) and was the major cause of SLE mortality prior to the advent of dialysis. Lupus nephritis can present with minimal laboratory abnormalities (non-nephrotic proteinuria, hematuria), frank nephritis (hypertension, lower extremity edema, active urine sediment, and elevated serum creatinine), and/or nephrosis (nephrotic-range proteinuria, dependent edema, and thrombosis). Untreated active disease may progress to kidney failure.

All patients with SLE should be regularly evaluated for kidney disease by assessing serum creatinine and urine for protein and microscopic evaluation. Patients with significant abnormalities, including proteinuria greater than 500 mg/24 h or active urine sediment, should be urgently evaluated for active disease. Anti–double-stranded DNA antibody titers are a marker for risk, and complement consumption is a common phenomenon during active kidney disease.

Kidney biopsy defines both the histological subtype and the activity/chronicity of disease and is usually essential to make therapeutic decisions. Indications for kidney biopsy include an otherwise unexplained rise in serum creatinine, proteinuria greater than 1000 mg/24 h, proteinuria greater than 500 mg/24 h with hematuria, or an active urine sediment.

Patients who have SLE with hypercoagulable states (for example, nephrosis or antiphospholipid syndrome) may be at risk for renal artery or vein thrombosis.

See MKSAP 18 Nephrology for information on the classes and treatment of lupus nephritis.

Neuropsychiatric Involvement

Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) may involve the central and/or peripheral nervous systems and has 19 defined manifestations. NPSLE prevalence is high (75%), with the most common manifestations being headache, mild cognitive dysfunction, and mood disorder. Peripheral neuropathy occurs in 10% to 14% of patients. Severe acute presentations, including seizures and psychosis, happen infrequently (<5%) but require aggressive symptomatic as well as disease-specific treatment.

Patients with suspected serious central NPSLE such as meningitis, stroke, and psychosis should undergo central nervous system imaging (CT, MRI, or PET) and cerebrospinal fluid analysis as appropriate. In some patients with severe disease, measurement of cerebrospinal fluid for NPSLE-associated autoantibodies (antineuronal, anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, antiribosomal P, and others) may be useful. For patients with suspected peripheral neuropathies, electromyography and nerve conduction studies should be performed. Neuropsychologic testing may help distinguish organic versus functional cognitive changes.

This patient has no sensory or motor deficits and presents with confusion, along with a nonfocal neurologic examination. She also shows signs of active SLE disease, including clinical evidence (fatigue, rash, arthritis) and laboratory findings (low complements and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate). She has elevated protein in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), and radiologic studies show diffuse white matter changes. These findings suggest that NPSLE is the likely cause for the mental status changes/psychosis and aseptic meningitis.

Cardiovascular Involvement

Asymptomatic pericarditis is the most frequent cardiac manifestation of SLE (40%). When symptomatic, features include chest pain, exudative effusion, and rarely tamponade or chronic constriction. Patients with SLE have a 2- to 10-fold increased prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD), the most common cause of death among older patients. High SLE disease activity and prednisone doses greater than 10 mg/d are independent risk factors for future CAD.

Valvular abnormalities occurring in SLE include those associated with antiphospholipid syndrome (nonspecific thickening of the mitral and aortic valve leaflets, vegetations, regurgitation, and stenosis). Libman-Sacks endocarditis (noninfectious verrucous vegetations) preferentially affects the mitral valve and can cause embolic complications. Myocarditis occurs in 5% to 10% of patients with SLE and usually presents as insidious heart failure but can be acute.

Patients who have SLE with positive antiphospholipid antibodies are at a high risk for developing valvular dysfunction/thickening, and in some cases manifesting as Libman-Sacks endocarditis. A recent study confirmed this significant association between valvular heart disease and antiphospholipid antibody positivity. It was also found that the highest risk was seen in double-positive antiphospholipid antibodies/lupus anticoagulant patients, as is the case in this patient. Libman-Sacks endocarditis may affect 11% or more of patients with SLE and has no relationship to disease activity. The condition is associated with large verrucous lesions near the edge of the valve, most often the mitral valve. Typical lesions consist of immune complexes, mononuclear cells, and fibrin and platelet thrombi. Libman-Sacks endocarditis is usually asymptomatic but can be responsible for numerous complications, including embolic stroke, or in this case a transient ischemic attack in the territory of the ophthalmic artery, peripheral emboli, and infective endocarditis.

Pulmonary Involvement

Pulmonary involvement is common in SLE, with most patients presenting with pleuritis (45%-60%). Pleural effusions occur in approximately half of these patients and are typically exudative; fluid analysis may reveal a lymphocytic pleocytosis and mildly depressed glucose levels.

Parenchymal lung involvement occurs in less than 10% of patients with SLE. A nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern is most common, and evaluation centers on assessing SLE activity and excluding other causes of diffuse parenchymal lung disease. Two rare but potentially life-threatening complications of SLE lung disease are acute lupus pneumonitis (presenting as fever, cough, dyspnea, hypoxemia, pleuritic chest pain, and infiltrates) and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (presenting with dyspnea, hypoxemia, diffuse alveolar infiltrates, a dropping hematocrit, and a high DLCO). Both carry a high mortality rate (>50%); early recognition, rapid evaluation (CT and/or bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage or biopsy), and aggressive respiratory support combined with high-dose glucocorticoids and immunosuppression are required. With new pulmonary infiltrates, differentiation between these disorders and infection can be difficult, and antibiotics and immunosuppressive therapy are often administered simultaneously until the diagnosis is clear.

Shrinking lung syndrome is a rare but characteristic syndrome consisting of pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea, with progressive decrease in lung volumes. The cause is uncertain, but pleuropulmonary disease and/or diaphragmatic dysfunction may contribute. Immunosuppression may reverse the process in some patients.

Hematologic Involvement

In patients with SLE, a normocytic, normochromic inflammatory anemia is common; autoimmune hemolytic anemia occurs in approximately 10% and correlates with SLE activity. Lymphopenia/leukopenia is also common but usually mild. Thrombocytopenia occurs in 30% to 50%, and approximately 10% of patients develop severe thrombocytopenia (<50,000/µL [50 × 109/L]) in isolation or in conjunction with hemolytic anemia.

The cytopenias in SLE may be caused by immune and nonimmune destructive mechanisms (including microangiopathy), medications, and kidney and liver disease. Moderate and severe or rapidly progressive cytopenias require prompt evaluation with serologic studies and/or bone marrow biopsy. An exact cause of cytopenias may be difficult to ascertain, and a trial of medication adjustment in concert with evaluation for other causes is often necessary.

Antiphospholipid antibodies/lupus anticoagulant (APLA/LAC) are frequently present in patients with SLE (about 40%) and may be associated with a false-positive rapid plasma reagin test for syphilis. Most patients are asymptomatic. Thrombotic events occur in about 30% and are associated with moderate or high titer of the antibodies; these include venous and arterial thrombosis, miscarriage, stillbirth, livedo reticularis, and cardiac valve thickening/vegetations. The highest risk of thrombosis occurs in the presence of triple positivity for LAC, anti-β2-glycoprotein I, and anticardiolipin antibodies. Patients with SLE are at increased risk for thrombotic events even in the absence of APLA. See MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology for more information.

Gastrointestinal Involvement

Gastrointestinal disease is a common (40%) and frequently underrecognized SLE manifestation. Serositis presents as abdominal pain, is usually associated with active disease, and improves with treatment. Mesenteric vasculitis, inflammation of the small and large bowel, pancreatitis, protein-losing enteropathy, and diffuse peritonitis are uncommon but may be severe and associated with cutaneous vasculitis. Patients with APLA can present with mesenteric thrombosis.

Noninfectious hepatitis can occur and is associated with the presence of antiribosomal P antibodies. Patients with SLE who have Raynaud phenomenon and anti-U1-ribonucleoprotein antibodies can develop esophageal disease and reflux.

Medications used to treat SLE (NSAIDs, prednisone, mycophenolate, azathioprine) also frequently affect the gastrointestinal system and may cause esophagitis, gastritis, pancreatitis, and other manifestations.

Association with Malignancy

The greatest malignancy risk among patients with SLE is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, presumably due to chronic B-cell activation and/or medications (azathioprine or cyclophosphamide). Other hematologic malignancies, including Hodgkin lymphoma and leukemia, are also increased. Lung cancer rates are increased slightly compared with the general population, probably related to smoking. Cervical cancer risk is increased, likely due to immunosuppression and increased prevalence of human papillomavirus.

Diagnosis

General Considerations

The diagnosis of SLE should be considered in any patient with unexplained symptoms affecting multiple organ systems or with any individual manifestation of SLE, especially in young women. At initial presentation, skin and joint manifestations are most common, along with constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss, or severe fatigue). Patients with subjective complaints of fatigue, myalgia, and/or arthralgia, but lacking objective findings, most likely have an alternative diagnosis and should not be evaluated for SLE.

In 2019, new SLE classification criteria were jointly developed by the European League Against Rheumatism and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). Although intended for accruing homogenous SLE populations for research studies, they can also be used to suggest a clinical diagnosis of SLE. The new classification system uses positivity for ANA as an entry criterion and weighted criteria grouped into 10 hierarchical domains (Figure 34). The presence of at least one clinical criterion and a threshold score of 10 are used to identify patients with probable SLE with a high degree of precision. These criteria are as sensitive as or more sensitive (96.1%) and specific (93.4%) than prior criteria from the ACR (Table 18) and the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics.

Classification criteria for SLE were developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 1982 and revised in 1997; although intended for accruing homogenous SLE populations for research studies, they can also be used to suggest a clinical diagnosis of SLE (Table 18). In 2012, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) proposed and validated alternative SLE classification criteria that are similar to the ACR criteria but require the following: 1) fulfillment of at least four criteria, with at least one clinical criterion and one immunologic criterion; or 2) biopsy-proven lupus nephritis as sufficient clinical criterion in the presence of ANA or anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies. When compared with the ACR classification criteria, the SLICC classification criteria are associated with fewer misclassifications and have greater sensitivity but less specificity.

Laboratory Studies

Initial evaluation for SLE includes routine laboratory testing to establish organ-specific involvement, including complete blood count, chemistry panel, and urinalysis with microscopy.

ANA should be obtained to screen for nuclear-directed autoantibodies. The most appropriate methodology for testing ANA is the indirect immunofluorescence assay, which is highly sensitive (95%) for SLE. ANA tests should be interpreted in the context of the probability of disease because ANA may be present in other autoimmune diseases, and low-titer positivity may be seen with aging and even in healthy individuals.

If ANA is positive, SLE-specific autoantibodies (anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith, anti-U1-ribonucleoprotein, anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SSB), as well as tests for other autoimmune diseases under consideration, should be obtained to further characterize the disease (Table 19). A small percentage of patients with SLE are negative for ANA but positive for anti-Ro/SSA antibodies. A negative ANA plus a negative anti-Ro/SSA essentially rules out SLE.

Disease activity markers (complements C3 and C4) should be assessed initially and regularly thereafter. Complement levels are reduced during SLE activity, reflecting immune complex formation and complement consumption. Anti–double-stranded DNA antibody levels may rise with SLE kidney disease activity. Other SLE autoantibodies, including the ANA test, do not reflect disease activity and need not be repeated. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are variably associated with disease activity; some patients with SLE do not generate CRP during SLE flares, which may be helpful in distinguishing flares from infection.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of SLE includes multisystem diseases, acute and chronic infections, medication effect, malignancies (particularly hematologic), and neurologic diseases (for example, multiple sclerosis). Multisystem autoimmune diseases (ANCA-associated vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis, adult-onset Still disease, dermatomyositis, Sjögren syndrome, and mixed connective tissue disease) have overlapping features but may be distinguished through a careful assessment of their unique manifestations.

SLE should also be distinguished from undifferentiated connective tissue disease, which presents with milder symptoms and objective abnormalities that cannot be categorized or diagnosed as a specific connective tissue disease (see Mixed Connective Tissue Disease).

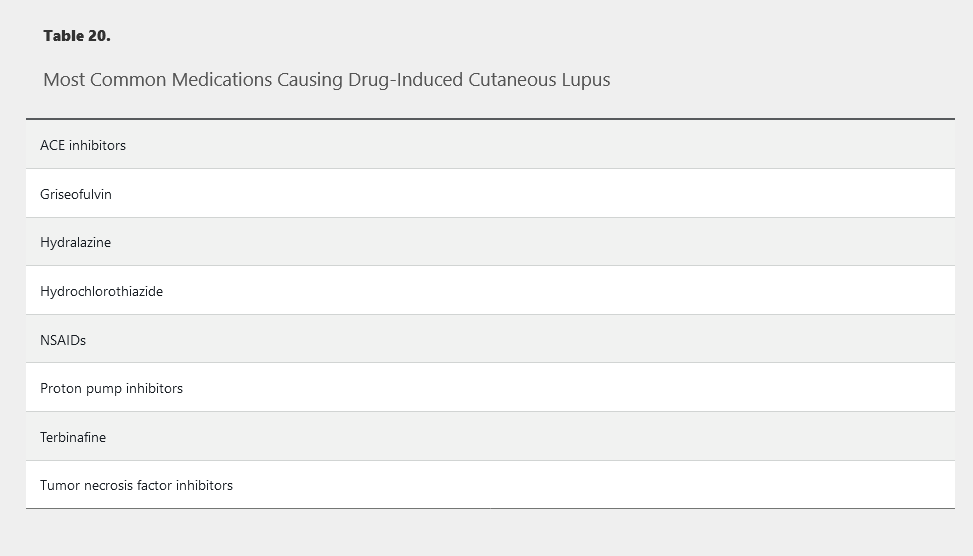

Certain medications can cause drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE), which mimics SLE (Table 20). The syndrome is usually mild with symptoms of malaise, fever, arthritis, and rash associated with a transient positive ANA and antihistone antibodies. Symptoms resolve after discontinuing the offending agent. Kidney and central nervous system disease are uncommon. Patients with SLE are at no more risk of DILE than the general population, and there is no contraindication to using medications associated with DILE in patients with SLE.

Management

SLE management requires close monitoring of disease activity and frequent adjustment of therapy. Pharmacologic therapy is almost always required and is usually directed toward specific organ involvement (Table 21). Goals of SLE treatment are remission or low disease activity and prevention of flares in all organs.

Hydroxychloroquine should be initiated in every patient who can tolerate it, because evidence suggests it reduces disease-associated damage, prevents disease flares, and improves kidney and overall survival. Hydroxychloroquine can be used alone for mild disease (especially skin and joints) and in combination with other agents in severe disease. In addition, hydroxychloroquine may reduce the risk of thrombosis, liver disease, and myocardial infarction; improve lipid profiles; and improve outcomes in high-risk pregnancies.

Glucocorticoids are a mainstay of SLE management, particularly in acute disease. The glucocorticoid dose should be determined by the level of disease activity and organ systems threatened. For severe disease activity (including profound cytopenias, class III/IV nephritis, and NPSLE), high-dose glucocorticoids are recommended. For life- or organ-threatening disease (such as rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis or seizures), high-dose intravenous glucocorticoids are given followed by high-dose daily prednisone. After disease stability is achieved, glucocorticoids are tapered to the lowest effective dose, ideally to eventual discontinuation.

Immunosuppressive therapy is usually initiated concurrently with glucocorticoids to achieve and maintain disease control and to allow tapering of glucocorticoids. Intravenous cyclophosphamide is used as induction therapy for severe or refractory disease (for example, severe active nephritis, acute central nervous system lupus, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, or myocarditis) followed by maintenance therapy with mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. Mycophenolate mofetil is currently the preferred oral agent for lupus nephritis and is as effective as cyclophosphamide for induction therapy. The biologic agent belimumab is FDA approved for patients with incomplete response to conventional treatments and has been shown to be useful in skin/joint involvement and moderate/severe disease.

Importantly, mycophenolate mofetil is teratogenic and has been associated with fetal harm and death; it must be stopped 3 months before a planned pregnancy.

NSAIDs can be used as adjunct therapy for arthritis and pleuropericarditis, but are not disease modifying and may adversely affect kidney function and blood pressure.

See Principles of Therapeutics for information on SLE medication toxicities, monitoring parameters, and more. See MKSAP 18 Nephrology for details on the treatment of lupus nephritis.

Pregnancy and Childbirth Issues

SLE is associated with a five- to eightfold increase in miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, and intrauterine growth retardation. Outcomes are worse in patients with active disease, nephritis, or anti-Ro/SSA and/or APLA antibodies. The best time to consider pregnancy is when SLE is quiescent, and conception should be considered only after at least 6 months of adequate disease control.

Proteinuria may increase during pregnancy in patients with SLE, making distinction between SLE and preeclampsia/eclampsia a challenge. Increases in anti–double-stranded DNA antibody levels, decreasing complement levels, or the development of active urine sediment suggests SLE as the cause. In contrast, serum urate levels are increased in preeclampsia but not during SLE flares.

Fetuses of women who have anti-Ro/SSA or anti-La/SSB antibodies are at risk for neonatal lupus erythematosus, which is characterized by rash and congenital heart block (CHB). Although the risk of CHB in the offspring of an anti-Ro/SSA–positive woman is only 2%, it is associated with significant fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. After a woman bears a child with neonatal lupus erythematosus, the risk of CHB is substantially increased (20%) in subsequent pregnancies. Hydroxychloroquine may reduce the overall risk.

Management of medications during SLE pregnancy is complicated. Hydroxychloroquine and low-dose glucocorticoids can be started during or continued throughout the pregnancy. Higher-dose glucocorticoids can be used to treat flare-ups or end-organ involvement. The preferred immunosuppressive agent for SLE during pregnancy is azathioprine, which should be used only if absolutely necessary. Belimumab, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide should be avoided. Cyclophosphamide is associated with age- and dose-dependent infertility. See Principles of Therapeutics for information on medications and pregnancy.

Prognosis

The prognosis in SLE has improved significantly, and there is now a 90% 5-year survival rate. Early mortality is usually related to SLE disease and infections, and late mortality related to cardiovascular disease. Factors adversely affecting survival include myocarditis, nephritis, low socioeconomic status, male gender, and age over 50 years at diagnosis. SLE tends to be a chronic waxing and waning disease with only 2% of patients achieving remission at 5 years.