Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Introduction

Skin infections usually result from epidermal compromise that allows skin colonizers such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes to become pathogenic. Predisposing conditions include vascular disease, immunodeficiency, neuropathy, previous cellulitis, obesity, skin trauma, tinea pedis, and lymphedema. Infections can be characterized by anatomic involvement and presence or absence of pus. Nonpurulent spreading skin infections include erysipelas, cellulitis, and necrotizing soft tissue infection; purulent skin infections refer to abscesses (Figure 2), furuncles, and carbuncles. Purulent skin infections are generally caused by staphylococci, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); nonpurulent skin infections are usually caused by β-hemolytic streptococci. Table 7 includes other skin pathogens and their associated risk factors for less common causes of skin infection. Complications of infections include systemic inflammatory response (as in severe cellulitis) or systemic toxin release (as in toxic shock syndrome).

Erysipelas and Cellulitis

Erysipelas refers to infection of the epidermis, upper dermis, and superficial lymphatics. Usually involving the face or lower extremities, this infection is brightly erythematous with distinct elevated borders and associated fever, lymphangitis, and regional lymphadenopathy (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology). Cellulitis refers to infection involving the deeper dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue. Inflammatory signs of infection are similar to erysipelas, but the area of involvement is less well demarcated.

Although the diagnosis of erysipelas or cellulitis is usually established clinically, approximately one third of patients are misdiagnosed. Clinical mimics include contact or stasis dermatitis, lymphedema, erythema nodosum, deep venous thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, lipodermatosclerosis, erythromelalgia, trauma-related inflammation, and hypersensitivity reactions (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology). Blood culture results are positive in approximately 5% of patients with erysipelas and cellulitis and are not routinely indicated; however, cultures should be performed for those who are immunocompromised, exhibit severe sepsis, or have unusual precipitating circumstances, including immersion injury or animal bites. Culture of skin tissue aspirate or biopsy should also be considered for these patients. Radiographic imaging is not helpful for the diagnosis of erysipelas or cellulitis but may be helpful when a deeper necrotizing infection is suspected.

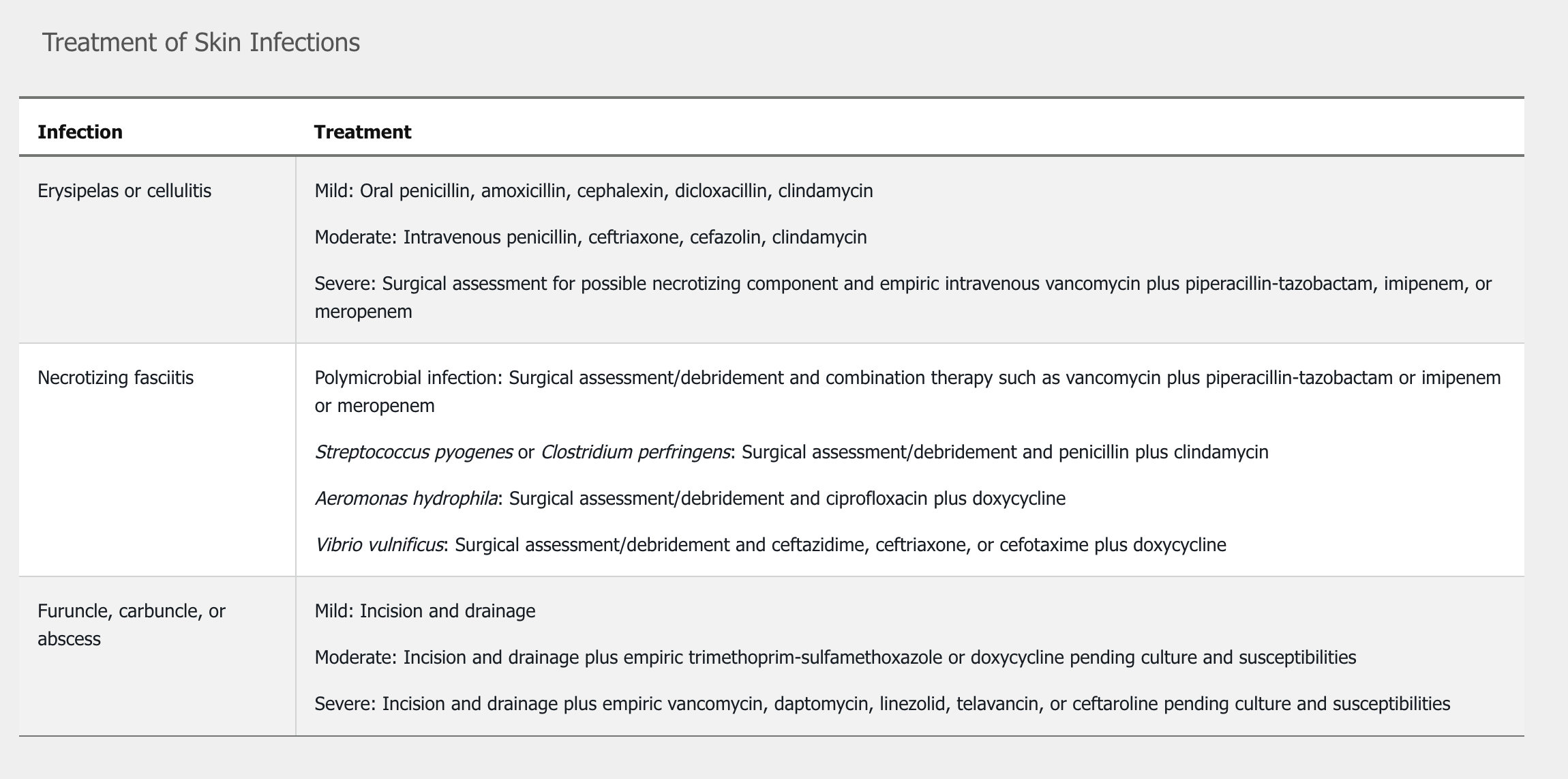

For immunocompetent patients with cellulitis or erysipelas who have no systemic signs or symptoms (mild infection), empiric oral therapy directed against streptococci is recommended as outlined in Table 8 (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology). Treatment duration for uncomplicated infection can be as short as 5 days but should be extended as necessary until the infection improves. In patients with systemic signs (moderate infection), intravenous treatment is recommended (see Table 8). Treating predisposing factors (such as tinea pedis, edema, and primary skin disorders) may decrease the risk for recurrent infection. Prophylactic antibiotics such as penicillin or erythromycin can be considered in patients with more than three episodes of cellulitis annually.

[!NOTE] Nonpurulent mild: strep. Treat with oral clinda, cephalexin Doxy/bactrim/clinda more for purulent and staph infections

Patients who are immunocompromised, who have systemic inflammatory response syndrome and hypotension, or who have evidence of deeper necrotizing infection such as bullae and desquamation (severe infection) should receive urgent surgical evaluation for debridement. Initial empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be started (see Table 8); then treatment may be adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results from lesion-associated specimens.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Necrotizing soft tissue infections, which involve subdermal compartments including fascia and possibly muscle, are uncommon but potentially life threatening. In necrotizing fasciitis (NF), infection usually spreads along the superficial fascia. These infections may be monomicrobial or polymicrobial, consisting of a mixture of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and are often associated with the production of toxins. In monomicrobial infection, the classically associated pathogen is Streptococcus pyogenes; other potential organisms include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Aeromonas hydrophila, Vibrio vulnificus, and Clostridium perfringens.

NF characteristically occurs in the setting of previous skin trauma or infection and most commonly affects the extremities. Risk factors include diabetes mellitus, injection drug use, malignancy, immunosuppression, and liver disease. Patients with liver disease are at particular risk for infection with V. vulnificus (Figure 3). Patients with diabetes are at risk for NF of the perineum, a polymicrobial infection known as Fournier gangrene that usually results from antecedent genitourinary, traumatic, or anorectal infection.

The initial presentation of NF resembles cellulitis before potentially rapid progression with edema, severe pain, hemorrhagic bullous lesions, skin necrosis, and local crepitus. Systemic toxicity manifests with fever, hypotension, tachycardia, mental status changes, and tachypnea. A hallmark of infection is “woody” induration appreciated by palpation of involved subcutaneous tissues. Necrosis of local nerves may result in anesthesia.

Necrotizing fasciitis involves destruction of the muscle fascia and overlying subcutaneous fat. Infection initially spreads along the fascia due to the poor blood supply of muscle fascia before it involves subcutaneous fat. As a result, early identification is difficult. Early findings include erythema spreading across muscle fascia, swelling, and exquisite tenderness out of proportion to its appearance. Infection spreads rapidly and the patient appears ill; tender areas become anesthetic due to impairment of the blood supply. At this stage, examination shows skin discoloration, crepitus, and hemorrhagic blisters. The swelling and edema can lead to compartment syndrome.

Laboratory study results are individually nonspecific. The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score is derived from six variables that, when added together, are associated with an increased likelihood of necrotizing skin infection: C-reactive protein level (>15 mg/dL, 150 mg/L), total leukocyte count (>15,000-25,000/µL, 15-25 × 109/L), hemoglobin level (<11-13.5 g/dL, 110-135 g/L), sodium level (<135 mEq/L, 135 mmol/L), creatinine level (>1.6 mg/dL, 141 µmol/L), and glucose level (>180 mg/dL, 10 mmol/L). This tool was developed to improve diagnostic accuracy; the reported positive and negative predictive values are 92% and 96%, respectively. However, use of the score has not been prospectively validated in all clinical settings, so operative debridement should be pursued in patients with a high index of clinical suspicion for NF.

Plain radiographs and CT scans may demonstrate gas in soft tissues, but MRI with contrast is more sensitive and can help delineate anatomic involvement. Surgical exploration can confirm the diagnosis of NF. Blood culture(s) obtained before surgery and antibiotic administration or deep intraoperative specimen culture can establish the microbiologic cause.

In confirmed cases of NF, repeated surgical debridement is typically required. Pending culture results, empiric antibiotic treatment includes broad-spectrum coverage for aerobic and anaerobic organisms (including MRSA) and consists of vancomycin, daptomycin, or linezolid plus piperacillin-tazobactam, a carbapenem, ceftriaxone plus metronidazole, or a fluoroquinolone plus metronidazole. Some experts also recommend adding empiric clindamycin because of its suppression of toxin production by staphylococci and streptococci. See Table 8 for treatment of NF caused by S. pyogenes, V. vulnificus, A. hydrophila, or clostridial species. Antimicrobial discontinuation can be considered when the patient is afebrile and clinically stable, and surgical debridement is no longer required.

Aeromonas species are found in aquatic environments, including fresh water and brackish water, and grow best during warmer months. Lacerations and puncture wounds sustained in these environments can result in wound infection. Aeromonas infections of the skin and soft tissue and of the bloodstream are more likely to occur in patients with underlying immunocompromising conditions, such as cirrhosis and cancer, and are more common in men. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by this gram-negative bacillus requires surgery, supportive care, and antibiotics. Pending culture data, empiric therapy for necrotizing skin infections typically consists of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as vancomycin plus piperacillin-tazobactam. When the diagnosis of A. hydrophila infection is established, doxycycline plus ciprofloxacin or ceftriaxone is recommended.

Purulent Skin Infections

Abscesses are erythematous, nodular, localized collections of pus within the dermis and subcutaneous fat. Furuncles (boils) are hair follicle–associated abscesses that extend into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. These inflammatory nodules are typically seen on the face, neck, and axilla. Infection that extends subcutaneously to involve several furuncles is known as a carbuncle. This coalescence of abscesses can result in systemic signs of infection.

Primary treatment for abscesses, furuncles, and carbuncles is incision and drainage. Gram stain and culture should be obtained from the purulent drainage when antibiotic administration is planned. Mild lesions without systemic symptoms do not require antibiotic therapy after drainage. For patients with moderate infections who have systemic signs of infection, empiric treatment is recommended (see Table 8). Empiric treatment with parenteral therapy is also recommended in immunocompromised patients, patients with hypotension and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (severe infection), or patients in whom incision and drainage plus oral antibiotics fail. Treatment is adjusted based on sensitivities from culture of the purulent drainage.

If MRSA is the cause of multiple recurrences of purulent skin infection, decolonization with topical intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine washes should be considered. Other diagnoses such as hidradenitis suppurativa, pilonidal cysts, or a foreign body should be considered when no microbial cause is identified.

Newer antibiotics for skin and soft tissue infections caused by Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species (including MRSA) include tedizolid, oritavancin, and dalbavancin. Use of these antibiotics is recommended in consultation with infectious disease specialists.

Animal Bites

Bites from cats and dogs represent approximately 1% of emergency department visits in the United States; most wounds (about 80%) will not become infected. Cat bites are more likely to become infected because of deeper puncture wounds created by cats' sharp, slender teeth. The microbiology of infection depends on the microbiota of the animal's mouth and of the patient's skin. Mixed aerobes and anaerobes, including staphylococci, streptococci, Bacteroides species, Porphyromonas species, Fusobacterium species, and Pasteurella species, typically compose the bacteria in bite wounds. Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a common constituent of canine microbiota and can cause severe infections in patients with asplenia.

Wound management includes irrigation with sterile normal saline. Irrigation also allows for characterization of wound extent and dimensions; signs of inflammation and infection, including edema, erythema, pain, necrosis, lymphangitis, and pus; and local neurovascular involvement. Surgical evaluation for possible debridement and removal of foreign bodies is particularly important with hand bites. Culture of deep intraoperative tissue and antibiotic susceptibilities of isolated organisms allows for pathogen-directed therapy. Radiographs may demonstrate fracture, other bony involvement, or foreign bodies. Assessment for tetanus and rabies prophylaxis is essential. With the exception of facial wounds, primary wound closure is not generally pursued.

The decision to begin early antibiotic prophylaxis in the absence of clinical signs of infection is based on the severity of the wound and the immune status of the patient. Because of its activity against pathogens associated with animal bite wounds, a 3- to 5-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate is recommended for patients who are immunosuppressed, including patients with cirrhosis and asplenia. Pre-emptive antibiotic therapy is also recommended for wounds with associated edema or lymphatic or venous insufficiency; crush injury; wounds involving a joint or bone; deep puncture wounds; or moderate to severe injuries, especially involving the face, genitalia, or hand. If a patient is allergic to penicillin, a combination of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or a fluoroquinolone, or doxycycline plus clindamycin or metronidazole can be used.

For clinically infected bite wounds, antibiotics are recommended after tissue wound cultures (and blood cultures, if systemic signs of infection are present) are obtained. For outpatient management of mildly infected wounds, oral antibiotics are recommended. The duration of antibiotic therapy is usually less than 2 weeks unless bone or joint involvement dictates a more prolonged course. Intravenous therapy is indicated for severe infections with systemic involvement, including sepsis; severe injuries, particularly those associated with tendon, nerve, vascular, or crush injuries; and hand infections. Intravenous antibiotic options include β-lactam or β-lactamase inhibitors (ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam), carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem), or ceftriaxone or a fluoroquinolone plus clindamycin or metronidazole. Empiric MRSA coverage may be included in patients with risk factors for MRSA infection (MRSA nasal colonization, recent hospitalization, recent antibiotic use, previous MRSA infection). Surgical consultation is usually obtained.

Clindamycin does not have good Pasteurella coverage. Do not use as monotherapy.

Human Bites

Intentional biting of others, self-inflicted wounds such as those occurring from fingernail biting, and clenched-fist injuries after a punch to another person's mouth are the most common causes of human bite wounds. These wounds are at risk for infection with human skin and mouth organisms. These organisms comprise aerobic organisms, including staphylococci, streptococci, and Eikenella corrodens, and anaerobic organisms, including Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella species. Short-course prophylactic antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanate is recommended for all human bites. The management of infected wounds is similar to that for animal bites, including empiric MRSA coverage in patients at increased risk for MRSA infection. Hand involvement warrants surgical evaluation. In addition to assessment for tetanus prophylaxis, evaluation for potential exposure to hepatitis B and C viruses, HIV, and other bodily fluid–transmitted pathogens is warranted.

Diabetic Foot Infections

Diabetic foot infections typically result after trauma in persons with vasculopathy, neuropathy, suboptimal glucose control, and immunologic deficits. Additional risk factors for infection include presence of an ulcer for greater than 1 month, recurrent ulcers, lower extremity amputation, kidney function impairment, walking barefoot, and a positive probe-to-bone test in the wound. Infection is diagnosed when pus or two or more inflammatory signs (warmth, induration, erythema, pain, and tenderness) are present.

Following debridement of overlying callous or necrotic tissue as necessary, infections should be classified according to severity and extent. Mild infections involve only skin and subcutaneous tissue with erythema confined to 2 cm beyond the ulcer. Moderate infections extend deeper than subcutaneous tissue (for example, abscess, fasciitis, and osteomyelitis), or the erythema is more extensive. Severe infections are associated with systemic signs such as fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, leukocytosis, and hypotension or metabolic complications such as acidosis, worsening kidney function, and hyperglycemia. The affected foot or limb should also be assessed for arterial ischemia, venous insufficiency, neuropathy, and biomechanical abnormalities such as Charcot arthropathy or hammer toe. Evidence of critical ischemia can be considered a proxy for severe infection.

Uninfected wounds should not be cultured or treated with antibiotics. Mild infections are typically caused by aerobic staphylococci (non-MRSA) and streptococci and can be empirically treated with a short course (7-14 days) of oral antibiotics, such as cephalexin, clindamycin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or dicloxacillin. For mild infections with pus or MRSA risk factors (previous MRSA infection or colonization within the last year or high local prevalence), wound cultures should be obtained by curettage or biopsy of deep tissue before initiating antibiotics. Doxycycline or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can also be used with a β-lactam antibiotic. For moderate and severe infections, polymicrobial coverage of staphylococci (including MRSA), streptococci, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes is recommended. Following deep-tissue culture, initial antibiotic regimens include β-lactam or β-lactamase inhibitors, carbapenems, or metronidazole plus a fluoroquinolone or third-generation cephalosporin in addition to an anti-MRSA agent (vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid). Antibiotic choices are guided by culture results. Moderate to severe infections are usually treated with a longer course of antibiotics (2-4 weeks); if osteomyelitis is present, approximately 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy is administered after surgical debridement.

A positive probe-to-bone test in a diabetic foot wound is associated with increased risk for osteomyelitis. Surgical consultation is often pursued to evaluate the need for debridement, resection, amputation, or revascularization. Plain imaging is recommended for all patients with new foot infections to assess for soft tissue gas, foreign body, and bony involvement; additional imaging with ultrasonography (for abscess) or MRI (for bone involvement) is recommended when clinically indicated. CT with intravenous contrast or a labeled leukocyte scan combined with a radionuclide bone scan can be considered when MRI is not possible. Wound care, glycemic control, and off-loading areas of biomechanical stress are essential.

Toxic Shock Syndrome

S. aureus– and S. pyogenes–associated exotoxins result in cytokine production that can result in toxic shock syndrome (TSS) (Table 9 and Table 10). Staphylococcal TSS is associated with tampon use, nasal packings, surgical wounds, skin ulcers, burns, catheters, and injection drug use. Streptococcal TSS is associated with skin and soft tissue infection, particularly NF. Bacteremia and mortality rates are higher with streptococcal than staphylococcal TSS. Source control typically requires surgical debridement. Antibiotics for streptococcal TSS consist of penicillin plus clindamycin, the latter added to eradicate the high inoculum of bacteria present and to suppress toxin production. If methicillin-susceptible S. aureus is the cause, nafcillin and clindamycin are recommended; for MRSA, vancomycin plus clindamycin or linezolid monotherapy is preferred. More studies are needed to establish the exact role of intravenous immune globulin in this setting, and it is not recommended in the most recent guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.