Sexually Transmitted Infections

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) occur most commonly in adolescents, young adults, and men who have sex with men (MSM), but STIs affect all demographics. Most infections are asymptomatic, so it is imperative that a detailed sexual history, including sexual practices, be obtained to understand individual risk. STI risk factors include a new partner, more than one current partner, a partner with an STI, or a partner who has concurrent partners. Particularly high-risk populations include persons attending STI clinics and MSM. The USPSTF recommends behavioral counseling to reduce the likelihood of acquiring STIs in sexually active adolescents and in adults at increased risk.

Unrecognized or inadequately treated upper genitourinary tract infection is a preventable cause of infertility in women. Evidence-based guidelines for the evaluation and management of STIs are available from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the CDC guidelines are recommended for use in the United States. Any patient diagnosed with an STI should be evaluated for other STIs, including HIV, and receive risk reduction counseling.

Chlamydia trachomatis Infection

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most commonly reported bacterial STI in the United States, and incidence has increased steadily over the past two decades. Screening of all sexually active women younger than 25 years is recommended. Women aged 25 years and older should be screened if they have STI risk factors. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that evidence is insufficient to support routine screening in men; the CDC recommends screening men in settings or populations with high prevalence or burden of disease (MSM, STI clinics).

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is preferred for screening and diagnosis. First-catch urine (for men and women) and endocervical (for women) or urethral (for men) swabs can be used. NAAT of urine samples for C. trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae has been shown to have a sensitivity and specificity nearly identical to tests obtained from urethral and endocervical samples. In addition to cervicitis and urethritis, chlamydia may cause oropharyngeal and rectal infection, and these sites should be evaluated based on history of sexual practices. Although commercially available, NAAT may not be FDA cleared for testing extragenital sites; laboratories can provide this testing if they have confirmed internal criteria for validity of test results.

Treatment of clinical syndromes caused by C. trachomatis is outlined in Table 32. Test of cure is not recommended, except in pregnancy. Because of the high risk of repeat infection, men and women should be retested after 3 months or the next time they are seen for medical care.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infection

The incidence of N. gonorrhoeae infection has been increasing since 2013, with rates of infection increasing more rapidly among men than women. Persons aged 20 to 24 years are at highest risk. In addition to cervicitis, urethritis, pharyngitis, and rectal infection, disseminated gonococcal infection (presenting as arthritis-dermatitis syndrome) can occur (see MKSAP 18 Rheumatology). Infection can be asymptomatic, especially in women, so screening is recommended for women younger than 25 years and those 25 years and older with STI risk factors. The USPSTF does not recommend screening for men; the CDC recommends screening men at high risk, as for C. trachomatis.

For screening and diagnosis, NAAT is preferred. Men and women can be screened using a first-catch urine sample; endocervical and urethral swabs may also be used. NAAT availability for samples from extragenital sites is limited, and physicians should determine what testing is available from their preferred laboratory. In patients with disseminated gonococcal infection (arthritis-dermatitis, endocarditis, or meningitis), all N. gonorrhoeae isolates should be tested for antimicrobial susceptibility. Patients with suspected disseminated gonococcal infection should have cultures performed on blood, joint fluid (if arthritis is present), purulent skin lesions (if present), and cerebrospinal fluid (if meningitis is suspected); however, culture yield is not high, so NAAT from all potential sites of exposure (genital, pharyngeal, rectal) should be obtained.

Treatment of _N. gonorrhoea_e is outlined in Table 32. Because of the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among N. gonorrhoeae isolates in the United States, cephalosporins are the only antimicrobial class recommended. Ceftriaxone plus azithromycin is no longer recommended for uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, or rectum. The CDC recommends ceftriaxone monotherapy for treatment because N. gonorrhoeae remains susceptible to ceftriaxone, and azithromycin resistance is increasing; the recommended dose of ceftriaxone has increased. In patients with an allergy precluding use of cephalosporins, oral gemifloxacin or parenteral gentamicin plus oral azithromycin is an option.

Test of cure is only recommended 2 weeks after therapy when pharyngeal gonorrhea is treated with an alternate antibiotic regimen. Patients with infections caused by N. gonorrhoeae who do not respond to treatment should have repeat testing with NAAT and culture so that susceptibility data can be obtained; consultation with an expert in the management of these infections should be sought.

Clinical Syndromes

Cervicitis

Women with cervicitis may present with vaginal discharge and intermenstrual bleeding, but many are asymptomatic. The major diagnostic criteria are (1) visualization of mucopurulent discharge from the cervical os or on a swab obtained from the endocervical canal and (2) eliciting bleeding by passing a swab into the cervical os; cervicitis should be considered in women with either of these findings. N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are the most commonly isolated pathogens; however, many cases are enigmatic. The role of Mycoplasma genitalium is still unclear; herpes simplex virus is occasionally implicated. Noninfectious causes (for example, chemical irritation from douching) should be sought. Patients should be tested for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis with NAAT; evaluation for bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis should also be performed (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine).

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Unrecognized pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) may result in long-term sequelae, including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy. Symptoms include lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, intermenstrual bleeding or bleeding after intercourse, and dyspareunia. Some women have fever and other signs of systemic toxicity, but this is uncommon.

The diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination is poor; however, because of the potential consequences of untreated infection, clinical findings with a high sensitivity for PID should be used. The presence of uterine tenderness, adnexal tenderness, or cervical motion tenderness is sufficient to make a clinical diagnosis of PID, especially if accompanied by mucopurulent cervical discharge.

PID is believed to be polymicrobial; however, testing only for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis is indicated. Most women can be managed in the ambulatory setting with oral antibiotics (see Table 32). Indications for hospitalization include inability to exclude a surgical emergency such as appendicitis, pregnancy, severe systemic toxicity, tubo-ovarian abscess, inability to tolerate oral antibiotics, and failure of initial outpatient management.

Urethritis

Men with urethritis present with dysuria, urethral pruritus, and discharge. Mucopurulent discharge may be the only symptom and is clinically diagnostic. N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and M. genitalium are common causes of urethritis; Trichomonas may also be causative. The role of other Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma species is uncertain at present. A first-catch urine sample should be tested for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis by NAAT for diagnosis and for public reporting purposes; FDA-approved tests for M. genitalium are not yet available. Microscopic examination of a urethral sample that reveals more than 2 leukocytes per high-powered field has a high positive predictive value for infectious urethritis, but the negative predictive value is poor. A positive leukocyte esterase test result or a microscopic examination with 10 or more leukocytes on a first-void urine specimen is also diagnostic for infectious urethritis. This testing is not required if mucoid, mucopurulent, or purulent urethral discharge is demonstrated on examination.

Epididymitis

Men with epididymitis present with unilateral pain and swelling in the epididymis; the testes may also be inflamed (epididymo-orchitis). Testicular torsion must be excluded in men with symptoms of sudden onset. N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are likely causes in younger, sexually active men. Older men and men who practice insertive anal intercourse may be infected with enteric gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli. NAAT for STI pathogens should be performed on first-catch urine, and a urine culture should be obtained. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for further information.

Anorectal Infections

Patients who present with anorectal pain, rectal discharge, or tenesmus should be questioned regarding sexual practices. In addition to receptive anal intercourse, infection may occur in women as a result of autoinoculation from vaginal discharge. Causes include C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, syphilis, and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Infections caused by the lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) serovars (L1, L2, or L3) of C. trachomatis had previously been rarely described in the United States, but they are increasingly reported as a cause of proctitis and proctocolitis, mainly among MSM.

Diagnostic evaluation should include NAAT of rectal swab for C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and HSV as well as serologic testing for syphilis (dark-field examination should be performed if available). Additional molecular testing is required to identify LGV serovars of C. trachomatis, but it is not widely available commercially; LGV serovars of C. trachomatis will be detected by currently available NAATs.

Treatment

Treatment of the clinical syndromes discussed previously is outlined in Table 32. Symptomatic patients evaluated in urgent care centers or emergency departments and others who may not be able to return for follow-up should be treated empirically based on clinical syndrome. Diagnostic testing should still be obtained because STIs are reportable and test results will be informative if the infection fails to respond to empiric therapy.

Patients should abstain from sexual contact for 7 days after completion of therapy and until all sexual partners have been treated. Sexual partners in the previous 60 days, or the most recent partner if greater than 60 days, should be referred for evaluation and treatment. Although independent evaluation and testing of sexual partners is preferred, most states have provisions for providing empiric antibiotic therapy prescriptions to the patient for their partners (expedited partner therapy, or EPT).

Genital Ulcers

Herpes Simplex Virus

The epidemiology of HSV genital ulcer disease is changing; in some populations, such as young heterosexual women and MSM, HSV-1 is now a more common cause of symptomatic primary infection than HSV-2. Although the clinical manifestations of primary infection by HSV-1 and HSV-2 are indistinguishable, HSV-1 is less likely than HSV-2 to cause symptomatic recurrent ulcers and subclinical shedding. Differentiation between the two viral subtypes is important in counseling patients regarding the natural history of their infection.

Primary infection presents as multiple painful lesions that begin as erythematous papules, progress to vesicles, then ulcerate, crust, and eventually heal within 2 to 3 weeks (Figure 12). Primary infection is often accompanied by significant systemic symptoms. Tender inguinal lymphadenopathy may be present.

Although the clinical manifestations of primary infection are quite characteristic, the viral cause and HSV subtype should be confirmed. NAAT, such as polymerase chain reaction, for HSV-1 and HSV-2 is preferred; other methodologies are far less sensitive. Testing is performed by obtaining a swab from the ulcer base; if only vesicles are present, a vesicle must be unroofed to obtain cells from the ulcer base. The swab must be placed in viral transport medium, so the appropriate sample collection kit must be used. Type-specific serologic testing is not advised for the diagnosis of symptomatic ulcer disease because patients can be seropositive for HSV-1 or HSV-2 yet have genital ulcers from another cause. Potential roles for serologic testing include testing a sexual partner when evaluating the potential benefits of long-term suppressive therapy because a partner who is already infected would not be at risk for transmission. The CDC recommends considering HSV serologic testing in persons who present for STI evaluation, MSM, and persons with HIV infection. Serologic screening in the general population is not recommended.

Antiviral therapy for primary infection has been shown to decrease time to resolution of symptoms, lesion healing, and viral shedding. Antiviral regimens appropriate for treatment of primary infection are outlined in Table 33.

Recurrent genital HSV infections are less severe, and symptom duration, time to lesion healing, and duration of viral shedding are reduced. Many patients will experience prodromal itching, burning, or tingling before ulcers appear. Atypical presentations such as fissures and excoriations may occur. Recurrent infection can be managed with either episodic self-start therapy (initiated within 24 hours of symptoms) or long-term suppressive therapy (see Table 33). Long-term suppressive therapy should be considered for persons with frequent recurrences and should be discussed with all patients because this strategy has been shown to decrease the risk of transmission to sexual partners. Laboratory monitoring is not required for patients undergoing long-term suppressive therapy; however, the continued need for therapy should be reviewed annually. Length of time since last recurrence and potential benefits of continued suppression in preventing transmission to sexual partners are factors that can inform the decision to stop suppressive therapy.

Patients should be counseled regarding the natural history of infection and informed that asymptomatic viral shedding is the most common source of HSV transmission to sexual partners. Condoms and abstinence from sexual activity when lesions are present can reduce the risk of transmission. Suppressive therapy to reduce risk of transmission should be discussed. Men and women should be counseled about the risks of neonatal HSV infection. Women should be advised to inform their obstetric provider and pediatrician of HSV infection in themselves or their sexual partner if they become pregnant.

Syphilis

The incidence of primary and secondary syphilis has been increasing in the United States since 2000. The USPSTF recommends screening nonpregnant adolescents and adults at high risk of infection. Persons at risk include MSM and commercial sex workers and those with HIV infection, multiple sex partners, and previous syphilis. In 2015, the CDC issued a clinical advisory regarding the increasing incidence of ocular syphilis.

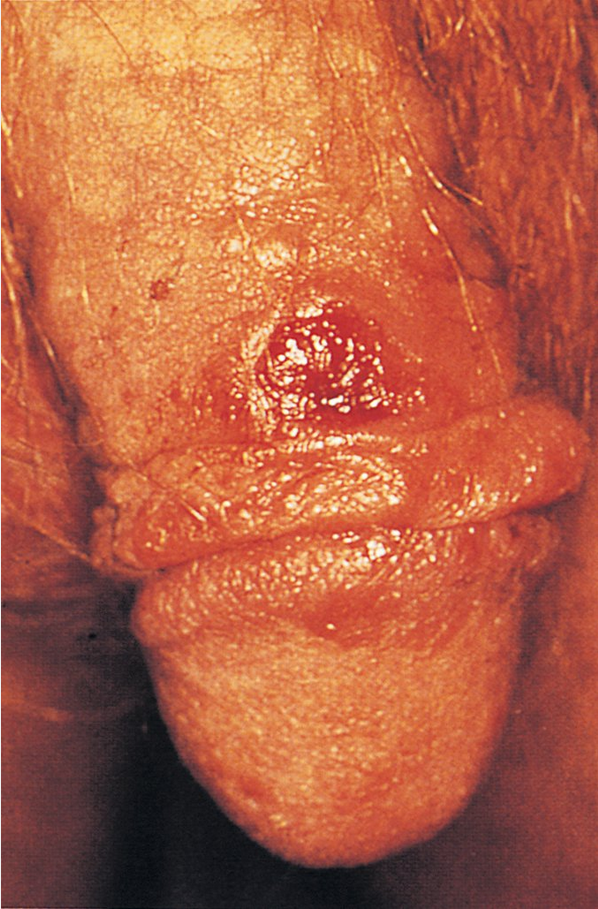

Primary syphilis presents as a painless genital ulcer (chancre) with a raised regular border that demonstrates firm induration on palpation (Figure 13). Several chancres may be present and may occur in the oral cavity. Regional lymphadenopathy may be present. The diagnosis of primary syphilis can be made on the basis of dark-field examination of material from a suspect lesion. Serologic test results may be negative in early primary infection. Even in the absence of treatment, lesions heal spontaneously in 3 to 6 weeks.

The primary ulcerative lesion (chancre) in patients with syphilis develops approximately 3 weeks after infection occurs, has a clean appearance with heaped-up borders, and is indurated and usually painless. It is often unrecognized.

The primary ulcerative lesion (chancre) in patients with syphilis develops approximately 3 weeks after infection occurs, has a clean appearance with heaped-up borders, and is indurated and usually painless. It is often unrecognized.

The most common manifestation of secondary syphilis is rash. Various morphologies are described; involvement of the palms and soles is characteristic. In intertriginous areas, papules may coalesce to form condyloma lata (plaque-like lesions). Mucous patches (superficial erosions on mucosal surfaces) may occur in the oral cavity and moist genital regions and are highly infectious. Prominent systemic symptoms and generalized lymphadenopathy are common. Uveitis and neurosyphilis (meningitis) can occur. Secondary syphilis manifestations can also resolve without treatment, followed by latent infection (a positive serologic test result without clinical manifestations). If latent infection is of less than 12 months' duration, it is termed early latent; if greater than 12 months' duration, it is late latent. Practically, these determinations can be made only if past serology results are available. Otherwise, patients are considered to have syphilis of unknown duration.

Tertiary syphilis is rarely seen in the United States, although neurologic disease still occurs. Spinal fluid examination should be sought in any patient with unexplained neurologic symptoms and serologic evidence of syphilis as well as in those who do not demonstrate an appropriate serologic response to syphilis treatment.

Diagnosis of secondary and tertiary syphilis relies on serologic testing. Many laboratories use the “reverse” serologic testing strategy, starting with an automated enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed by a nonspecific test (rapid plasma reagin or Venereal Disease Research Lab test). Patients with a positive enzyme immunoassay result but negative rapid plasma reagin or Venereal Disease Research Lab test result should have a second specific treponemal antibody test to confirm the result. Those with a confirmed positive result and no history of syphilis treatment should be offered treatment for syphilis of unknown duration. The treponemal test (EIA) remains positive indefinitely, but the nontreponemal test (RPR or VDRL) should remain negative. If the nontreponemal test became positive again, it would indicate a new infection, and treatment, based on disease stage, would be indicated. If this patient had reported no history of treatment for syphilis, she should be treated for syphilis of unknown duration, which consists of 3 weekly doses of intramuscular benzathine penicillin.

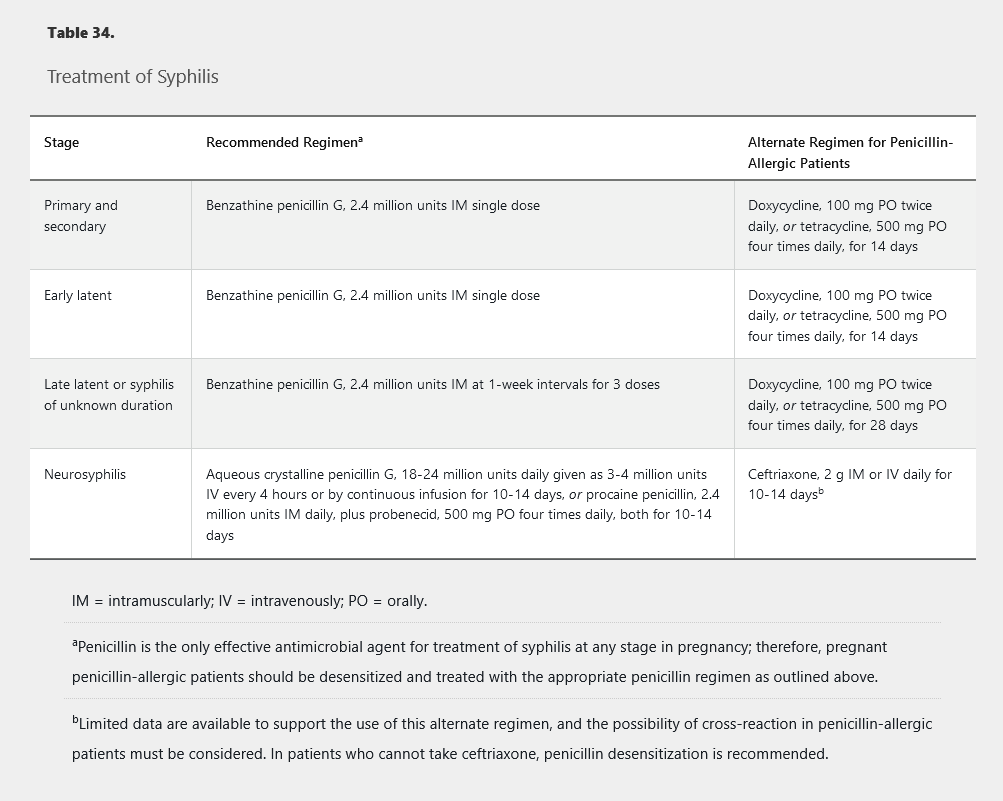

Syphilis treatment is outlined in Table 34. Sexual partners of those with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis exposed in the preceding 90 days should be treated regardless of serologic results.

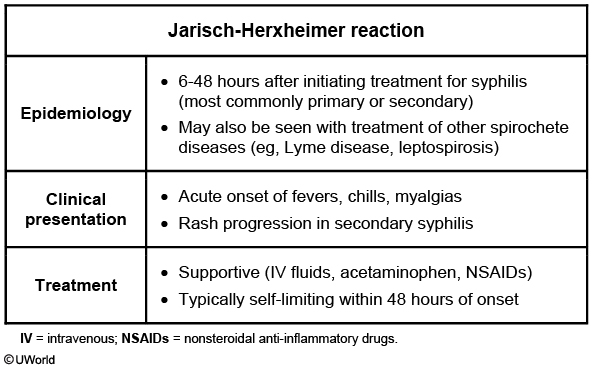

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

This patient with primary syphilis (chancre) received a dose of penicillin G last night and now has the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This reaction is seen primarily in patients with early syphilis treated with antibiotic medication. The rapid destruction of spirochetes causes an acute febrile illness, typically within 12 hours of treatment. Symptoms include headache, myalgias, rigors, sweating, hypotension, and worsened syphilitic rash (diffuse, macular, including palms and soles). Manifestations are usually self-limited and resolve spontaneously within 48 hours.

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction can also occur after the treatment of other spirochetes (eg, Borrelia burgdorferi) and atypical organisms (eg, Bartonella).

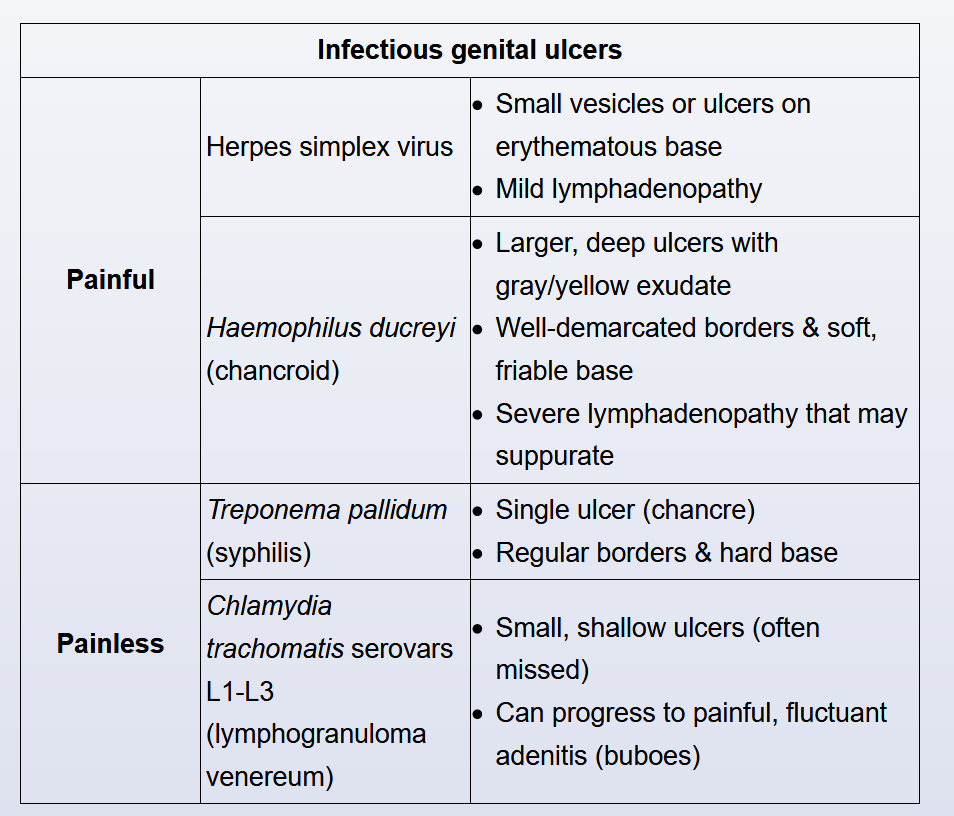

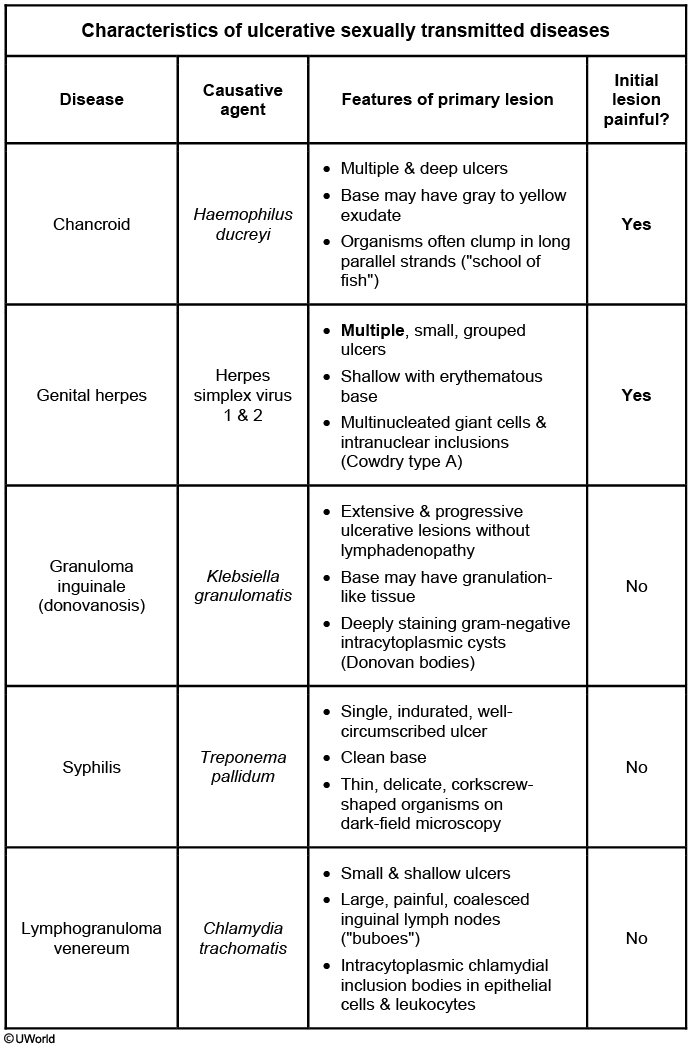

Chancroid and Lymphogranuloma Venereum

With the exception of proctitis or proctocolitis caused by the LGV serovars of C. trachomatis, these two STIs are rarely seen in the United States. The clinical presentation and evaluation are outlined in Table 35, and treatment is outlined in Table 36.

Genital Warts

Genital warts have a variety of appearances, including papular or pedunculated lesions (Figure 14). Larger, verrucous, exophytic lesions can occur. Most are asymptomatic; however, large lesions may cause irritation or pain depending on their location. Nononcogenic types of human papillomavirus (HPV) are responsible for most lesions. Oncogenic subtypes less commonly cause genital warts. HPV infection can be diagnosed based on the presence of lesions with a consistent morphologic appearance. Specific testing for HPV is not recommended for diagnosis.

Warts will often resolve without therapy, but treatment is indicated for symptomatic warts or if the cosmetic appearance of the warts is causing psychological distress. Patients should be counseled that successful treatment may not eliminate the risk of transmission. Therapy includes patient-applied or physician-administered modalities. Patient-applied therapies include imiquimod, podofilox, and sinecatechins; provider-administered therapies include trichloroacetic acid or bichloroacetic acid, cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or cryoprobe, or surgical removal. The modality chosen depends on size, number, and location of warts; patient preference; and provider experience. No evidence indicates superiority of any of the modalities recommended. Ulcerated or pigmented warts and those that fail to respond to or worsen after therapy should be biopsied to exclude a cancerous lesion.