Reproductive Disorders

- related: Endocrine

- tags: #endocrine

Physiology of Female Reproduction

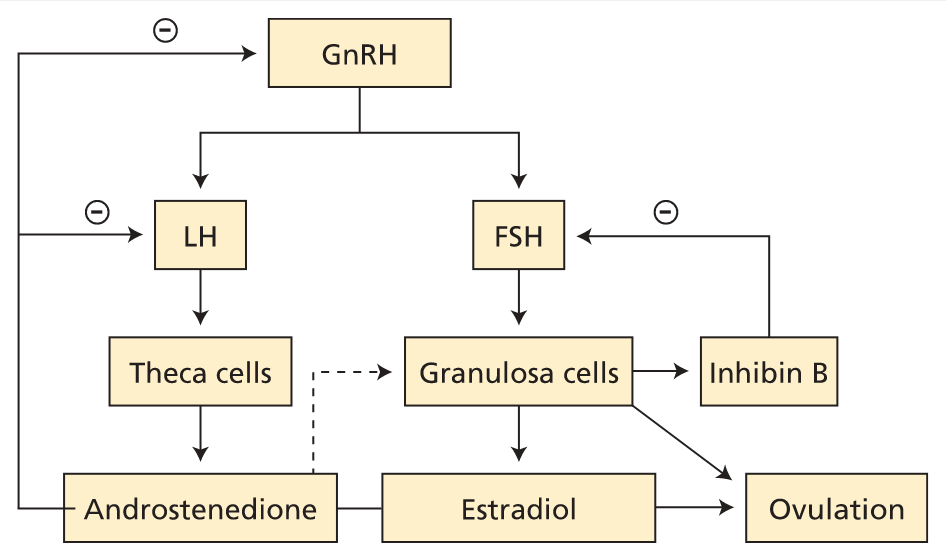

Coordinated actions of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries (known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis) give rise to ovulatory cycles in women. The pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) drives the anterior pituitary cells to secrete follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) (Figure 11). FSH regulates estradiol production and follicle growth in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. A sudden rise in LH levels causes release of an ovum midcycle, signaling the start of the luteal phase, which is a constant 14 days. Endometrial sloughing follows decreased estrogen or progesterone levels if a fertilized embryo does not implant. Menses occur every 25 to 35 days; menstrual cycles shorter than 25 days or longer than 35 days in women younger than age 40 years are likely anovulatory, resulting in abnormal uterine bleeding or oligomenorrhea. Before puberty, ovaries are quiescent due to immaturity of the hypothalamus. After menopause, all reproductive function and most endocrine function of the ovaries ceases.

Female reproductive axis. Pulses of GnRH drive LH and FSH production. LH acts on theca cells to stimulate androgen (principally androstenedione) production. Androstenedione is metabolized to estradiol in granulosa cells. FSH acts on granulosa cells to enhance follicle maturation. Granulosa cells produce inhibin B as a feedback regulator of FSH production. FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH = gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH = luteinizing hormone; − (circled) = negative feedback.

Amenorrhea

Amenorrhea, the absence of menses, can be intermittent or permanent. It may result from hypothalamic, pituitary, ovarian, uterine, or outflow tract disorders.

Clinical Features

Primary Amenorrhea

Primary amenorrhea is defined as absence of menses at age 15 years in the presence of normal growth and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary amenorrhea is most commonly caused by a genetic (50%) or anatomic (15%) abnormality. Most causes of secondary amenorrhea can also present as primary amenorrhea.

The most common cause of primary amenorrhea is gonadal dysgenesis, most commonly with Turner syndrome (45,X0). Turner syndrome is caused by loss of part or all of an X chromosome. It occurs in 1 in 2500 live female births. It is associated with short stature and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI); primary amenorrhea is seen in approximately 90% of patients with Turner syndrome.

Anatomic abnormalities that can cause primary amenorrhea include an intact hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and vaginal agenesis. Vaginal agenesis (also known as müllerian agenesis or Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome) is the second most common cause of primary amenorrhea, with an incidence of 1 in 5000 live female births. Women with vaginal agenesis have a normal female karyotype and ovarian function, and thus, normal external genitalia and secondary sexual characteristics.

Secondary Amenorrhea

Secondary amenorrhea is defined as absence of menses for more than 3 months in women who previously had regular menstrual cycles or for 6 months in women who have irregular menses. In women with oligomenorrhea, defined as fewer than nine menstrual cycles per year or cycle length longer than 35 days, the evaluation is the same as for secondary amenorrhea.

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) is caused by a disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and is the most common cause of secondary amenorrhea after pregnancy. Disruption of the pulsatile release of hypothalamic GnRH may occur due to stress, weight loss, or exercise. In many cases, all three factors are present. FHA is a diagnosis of exclusion; history and physical examination, biochemical testing, and, imaging, when appropriate, should be undertaken to rule out other causes of secondary amenorrhea including intracranial tumor, infiltrative or destructive disorders such as lymphocytic hypophysitis, histiocytosis X, sarcoidosis, Sheehan syndrome, and acute or chronic systemic illness.

Premenopausal women with hyperprolactinemia present more often with oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea than galactorrhea. Hyperprolactinemia accounts for 10% to 20% of non–pregnancy-mediated amenorrhea. Menstrual dysfunction in hyperprolactinemia results from inhibition of GnRH.

Menstrual dysfunction is common in women with thyroid disorders; while heavy bleeding is typical with hypothyroidism, secondary amenorrhea can also occur.

Hyperandrogenic disorders are associated with amenorrhea, with polycystic ovary syndrome by far the most common hyperandrogenic cause.

Spontaneous primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) can be diagnosed in women younger than age 40 years with menstrual dysfunction in association with two serum FSH levels in the menopausal range. POI affects 1 in 100 women. In addition to disordered menses, affected women may develop symptoms related to estrogen deficiency, such as vasomotor symptoms, sleep disturbance, and dyspareunia related to vaginal dryness. Most cases are sporadic, but a first-degree relative with POI suggests a familial etiology, whereas a personal history of autoimmune disorders can suggest an autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. Women with POI have increased risk for development of autoimmune adrenal insufficiency.

Intrauterine adhesions are the only uterine cause of secondary amenorrhea. Amenorrhea results from the development of scar tissue within the uterine cavity preventing build up and shedding of endometrial cells. Adhesions develop following uterine instrumentation, most commonly associated with uterine curettage for pregnancy complications (Asherman syndrome).

Evaluation of Amenorrhea

A thorough history and physical examination is the first step in evaluating amenorrhea. Important data include medication and illicit drug exposure, changes in weight, exercise history, psychosocial stressors, and family history related to menarche. Symptoms can include headaches or visual changes suggesting pituitary pathology, symptoms of thyroid excess or deficiency, galactorrhea suggesting hyperprolactinemia, or vasomotor symptoms associated with estrogen deficiency.

Physical examination should include a pelvic examination to evaluate the vagina, cervix, and uterus for abnormalities. Imaging may be necessary to confirm a normal uterus. Physical examination should also include evaluation for features of Turner syndrome, such as a low hairline, webbed neck, shield chest, and widely spaced nipples.

In patients with primary or secondary amenorrhea, measurement of height, weight, and BMI is important. A low BMI (<18.5) may suggest FHA due to an eating disorder, excessive exercise, or systemic illness. A high BMI (≥30) is frequently seen in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Additional physical examination findings suggestive of PCOS include acne and hirsutism. Hypercortisolism is associated with acne and hirsutism, as well as abnormal fat pad distribution, centripetal obesity, facial plethora, proximal muscle weakness, and wide (>1 cm) violaceous striae. Vitiligo or other signs of autoimmune disease increase the likelihood of autoimmune POI. Breast examination should include assessment for expressible galactorrhea. Vulvovaginal atrophy suggests estrogen deficiency.

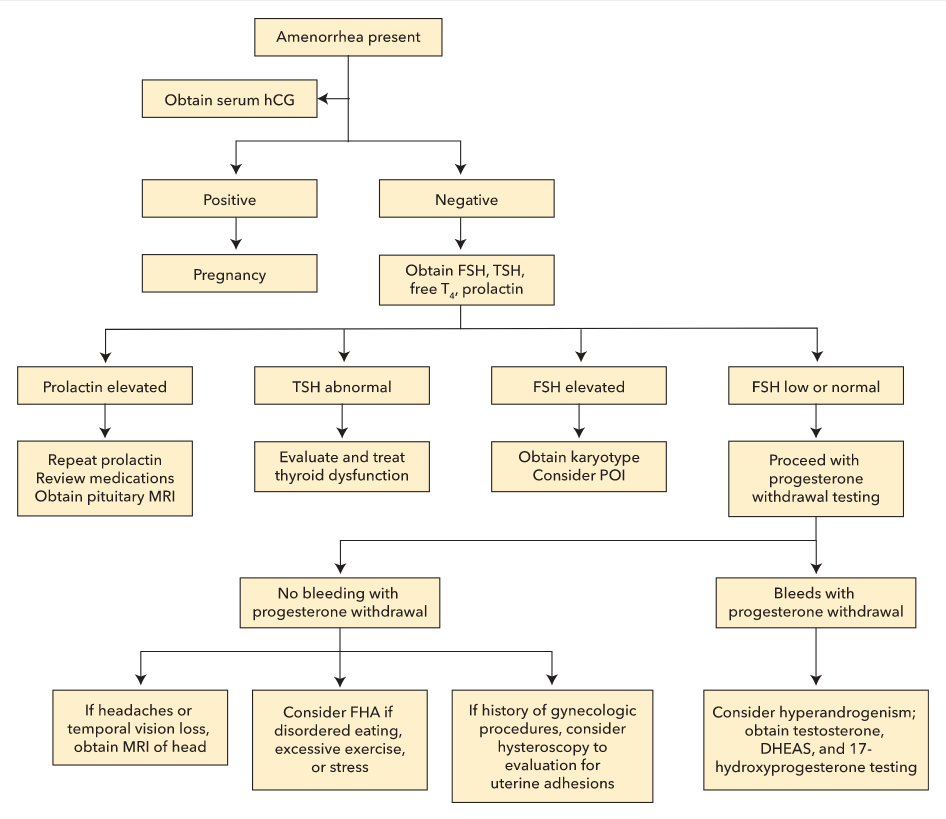

After ruling out pregnancy, initial laboratory testing in both primary and secondary amenorrhea should include measurement of FSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine, and prolactin levels. Next steps are guided by these laboratory results (Figure 12).

Algorithm for evaluating amenorrhea. FHA = functional hypothalamic amenorrhea; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; POI = primary ovarian insufficiency; T4 = thyroxine; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Algorithm for evaluating amenorrhea. FHA = functional hypothalamic amenorrhea; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; POI = primary ovarian insufficiency; T4 = thyroxine; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

If the TSH level is abnormal, evaluation and management of thyroid dysfunction should occur (see Disorders of the Thyroid Gland).

If the prolactin level is elevated, repeat prolactin testing is needed to confirm the diagnosis. A careful review of medications is essential because many drugs can cause hyperprolactinemia. Kidney and liver function testing is also required (see Disorders of the Pituitary Gland).

If the FSH level is elevated, testing should be repeated in 1 month with simultaneous serum estradiol testing. If the FSH level is elevated on repeat testing and estradiol level is low, karyotype analysis is indicated to evaluate for Turner syndrome. POI and menopause also cause elevated FSH levels.

In women with normal or low FSH levels, the history and physical examination findings determine next steps. Further assessment of estrogen status can be determined by a progestin withdrawal test. If a normal estrogen state is confirmed (bleeding within a week of stopping progesterone), hyperandrogenism should be considered. Laboratory evaluation for hyperandrogenism includes measurement of total testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels. PCOS is the most likely cause of menstrual dysfunction in women with hyperandrogenism; however, other hyperandrogenic disorders must be excluded before diagnosing PCOS. If no bleeding occurs, a low-estrogen state due to hypothalamic hypogonadism is most likely.

Imaging studies that can be utilized in the evaluation of amenorrhea include MRI of the sellar region (to evaluate for structural integrity of the pituitary), pelvic ultrasound (to assess for anatomic abnormalities of uterus, vagina, and ovaries), hysterosalpingogram and hysteroscopy (to assess for uterine outflow obstructions). Choice of imaging study, as well as necessity of imaging at all, is predicated on prior biochemical test results indicating the cause of the amenorrhea.

Treatment of Amenorrhea

Almost all women with Turner syndrome will need exogenous estrogen therapy with cyclic progestin to prevent endometrial hyperplasia. Estrogen-progestin therapy is continued until age 51 years, the average age of menopause.

Treatment for FHA includes less-restrictive eating patterns, weight gain, or a reduction in strenuous exercise to restore menses. Additionally, it is important to treat conditions associated with FHA, including low bone mass, eating disorders, anxiety, and other mood disorders.

Amenorrhea due to hyperprolactinemia with a lactotroph adenoma is managed with dopamine agonist therapy if fertility is desired, or with estrogen/progestin if not, to prevent bone loss. If hyperprolactinemia-induced amenorrhea is related to medications that cannot be stopped (such as antipsychotic agents), estrogen/progestin therapy is indicated.

Treatment of POI includes estrogen/progestin therapy until approximately age 51 years. Psychosocial support is important due to higher scores on depression, anxiety, and negative affect scales in patients with POI; subspecialty consultation to discuss fertility options is also indicated.

Treatment of vaginal agenesis includes nonsurgical vaginal dilation; surgical options can be considered if nonsurgical therapy fails.

Hyperandrogenism Syndromes

Hirsutism and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Elevated serum concentrations of androgens in women most commonly manifest with hirsutism and may also present with acne, androgenetic alopecia, and/or virilization. Hirsutism is the presence of excessive terminal hair in male-pattern growth distribution; it affects approximately 10% of women. Virilization (voice deepening, clitoromegaly, male pattern baldness, severe acne) occurs only in severe hyperandrogenism and raises concern for ovarian hyperthecosis or an androgen-producing ovarian or adrenal tumor. Onset of hirsutism in a woman older than age 30 years also raises concern for an androgen-producing tumor. Although androgen-secreting ovarian tumors are rare, they should be considered in patients with abrupt, rapidly progressive hirsutism or severe hyperandrogenism as well as in women with marked hyperandrogenemia (total testosterone >150 ng/dL, 5.2 nmol/L).

Women with chronic hirsutism and menstrual cycles every 25 to 35 days most likely have idiopathic hirsutism or PCOS. Fifteen to 40% of women with hyperandrogenism and menses every 21 to 35 days have ovulatory dysfunction. PCOS is the most common cause of hirsutism, accounting for 95% of cases.

PCOS is a disorder characterized by hyperandrogenism and ovulatory dysfunction. PCOS affects 6% to 10% of women and is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility in women. It is associated with rapid GnRH pulses, an excess of LH, and insufficient FSH secretion, resulting in excessive ovarian androgen production and ovulatory dysfunction. It is accompanied by insulin resistance. Elevated insulin levels in PCOS further enhance ovarian and adrenal androgen production, as well as increase bioavailability of androgens related to a reduction in SHBG. PCOS is associated with increased incidence of metabolic syndrome, prediabetes, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity.

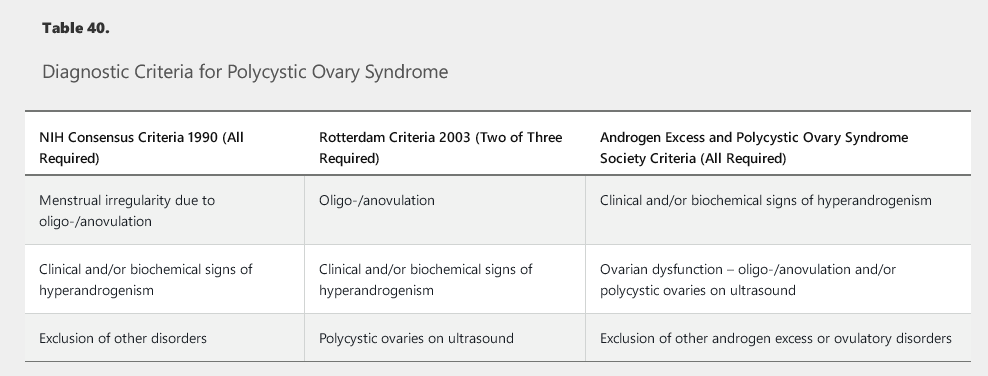

There are a variety of diagnostic criteria for PCOS (Table 40). It is important to remember that PCOS is a diagnosis of exclusion; other causes of oligo-/anovulation must be considered including thyroid dysfunction, nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinemia, and androgen-secreting tumors.

Although most women with hirsutism (excess terminal hair growth) have polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), rapid-onset hirsutism, with or without virilization (eg, vocal deepening, excessive muscular development, clitoromegaly), suggests very high androgen levels due to an androgen-secreting neoplasm of the ovaries or adrenal glands.

The primary ovarian androgens include testosterone, androstenedione, and dehydroepiandrosterone. The adrenals produce these as well as dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS). Therefore, women with a suspected androgen-producing tumor should be evaluated with serum testosterone and DHEAS levels:

- Elevated testosterone levels with normal DHEAS levels suggest an ovarian source (more common).

- Elevated DHEAS levels suggest an adrenal tumor (far less common).

DHEAS and DHEA have negligible intrinsic androgenic action but are converted to androstenedione and subsequently to testosterone in peripheral tissues. Some adrenal tumors can also directly produce testosterone.

Evaluation of Hyperandrogenism

The history and physical examination should include details about the onset of hirsutism and other symptoms/signs of hyperandrogenism, menstrual history, family history of hyperandrogenism, signs of insulin resistance (obesity, acanthosis nigricans, skin tags), distribution of terminal hair growth, and hair loss. Exposure to exogenous testosterone (topical, oral, or injected) should be assessed as a possible cause of hyperandrogenism and virilization.

Women with hirsutism should have total testosterone with SHBG measured, as well as morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone to screen for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Laboratory evaluation for oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (human chorionic gonadotropin hCG, prolactin, FSH, TSH, free thyroxine) is also indicated. Serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) measurement should be obtained in cases of recent onset of rapidly progressive hirsutism and/or virilization.

Patients with PCOS may have modestly elevated DHEA-S levels; additionally, this patient has no features to suggest an androgen-secreting tumor.

Markedly high DHEAS and/or testosterone levels are not consistent with PCOS. Patients with total testosterone levels greater than 200 ng/dL (6.9 nmol/L) or DHEAS values greater than 700 µg/mL (18.9 μmol/L) require imaging to assess for adrenal tumor (adrenal CT or MRI) or ovarian tumor (transvaginal ultrasound).

Management of Hyperandrogenism

Mechanical hair removal (threading, depilatories, electrolysis, laser) may be adequate for cosmesis in women with idiopathic hirsutism. First-line pharmacologic management of hirsutism is combined hormonal (estrogen-progestin) oral contraceptive agents; these agents suppress gonadotropin secretion and ovarian androgen production, as well as increase SHBG levels. Antiandrogen therapy (spironolactone) can be added for a better cosmetic response; concomitant contraception is mandatory with this therapy due to teratogenesis in male fetuses. Topical eflornithine is also approved for treatment of unwanted hair growth.

In PCOS, weight loss is a first-line intervention in patients with BMI of 25 or greater. Sustained weight loss of 5% to 10% improves androgen levels, menstrual function, and possibly fertility. Oral contraceptive agents are first-line pharmacologic therapy for hirsutism and menstrual dysfunction unless fertility is desired. An antiandrogen agent is added after 6 months if cosmesis is suboptimal with oral contraceptive agents (spironolactone). Spironolactone is also recommended in patients with contraindications to OCPs. If fertility is desired, clomiphene citrate or letrozole can be used to correct oligo-/anovulation. Metformin reduces hyperinsulinemia and androgen levels but has minimal impact on hirsutism and ovulation.

Patients with PCOS should be screened for prediabetes/diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea due to increased risk for these conditions. Metformin is indicated when impaired glucose tolerance, prediabetes, or type 2 diabetes mellitus does not respond adequately to lifestyle modification.

Female Infertility

Infertility evaluation is appropriate after 1 year of unprotected intercourse, on average twice weekly, in women younger than age 35 years and after 6 months in women age 35 years or older. Treatment of infertility is typically managed by a reproductive endocrinologist. Both partners should be evaluated concurrently; often, multiple factors are present (see Male Infertility).

History and physical examination findings may suggest the cause of infertility. Key factors include menstrual history (to determine ovulatory status) and assessment for thyroid dysfunction, galactorrhea, hirsutism, pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia. History of previous pregnancies, cancer therapy, substance use disorder, sexually transmitted infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, and gynecologic procedures should be explored. Frequency of coitus is important information. Physical examination should include BMI and assessment for signs of hyperandrogenism, estrogen deficiency, hyperprolactinemia, and thyroid dysfunction.

Assessment of ovulatory function is the first step in evaluation. Women with menses approximately every 28 days with molimina symptoms (breast tenderness, abdominal bloating, ovulatory pain) are likely ovulatory. In women without such cycles, assessment of ovulatory status is assessed with a midluteal phase serum progesterone level (obtained 1 week before the expected menses); a progesterone level greater than 3 ng/mL (9.5 nmol/L) is evidence of recent ovulation. If anovulatory cycles are suspected, the initial evaluation includes prolactin, TSH, and FSH measurements, with subsequent assessment for PCOS.

Hysterosalpingogram is used to assess for tubal occlusion and to evaluate the uterine cavity. Exploratory laparoscopy may be used if endometriosis or pelvic adhesions are suspected. If no abnormalities are found, fertility treatments will be offered under the direction of a reproductive endocrinologist, possibly including ovarian stimulation with clomiphene citrate or letrozole, intrauterine insemination, and in vitro fertilization, which may be offered to women age 40 years or older as first-line therapy.

Physiology of Male Reproduction

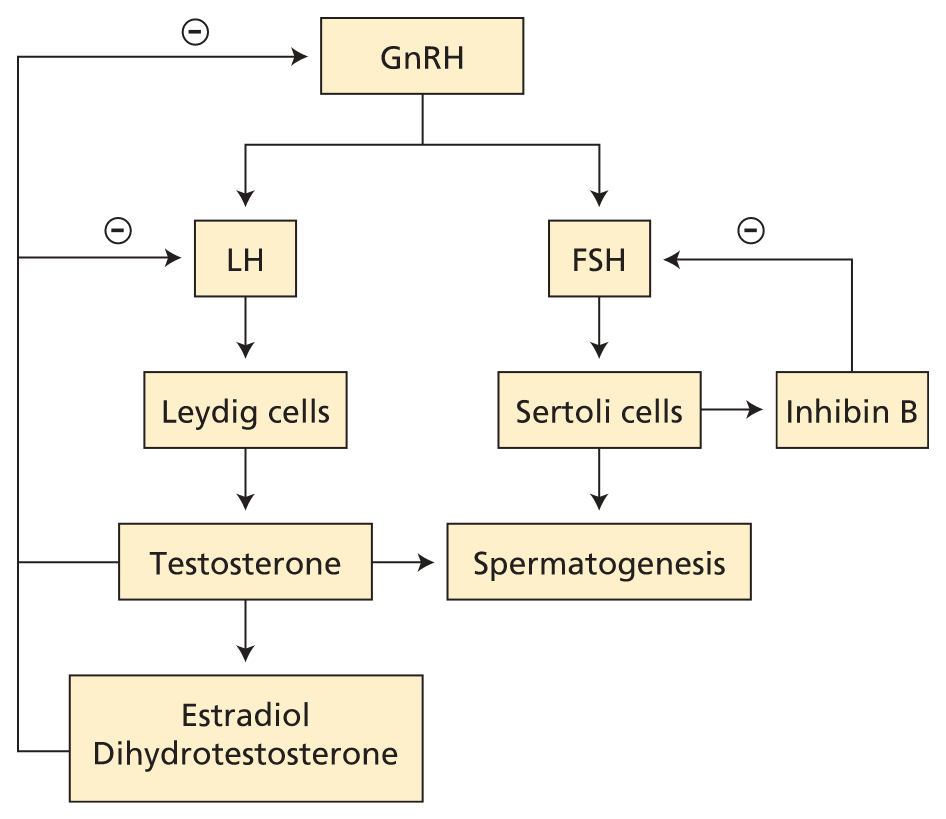

The testes contain two anatomical units: the spermatogenic tubules composed of germ cells and Sertoli cells, and the interstitium containing Leydig cells. The three steroids of primary importance in male reproduction are testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and estradiol. It is the pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) by the hypothalamus that elicits pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) by the gonadotroph cells of the anterior pituitary.

LH regulates testosterone synthesis in Leydig cells in a diurnal pattern; LH secretion is regulated by negative feedback of testosterone and estradiol. FSH regulates Sertoli cell spermatogenesis. Inhibin B is an important peptide inhibitor of pituitary FSH secretion (Figure 13). The hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis is sensitive to stressors, including acute and chronic illness, fasting, and strenuous exercise, all of which can lower testosterone levels.

Male reproductive axis. Pulses of GnRH elicit pulses of LH and FSH. FSH acts on Sertoli cells, which assist sperm maturation and produce inhibin B, the major negative regulator of basal FSH production. The Leydig cells produce testosterone, which feeds back to inhibit GnRH and LH release. Some testosterone is irreversibly converted to dihydrotestosterone or estradiol, which are both more potent than testosterone in suppressing GnRH and LH. FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH = gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH = luteinizing hormone; − (circled) = negative feedback.

Hypogonadism

Causes

Male hypogonadism is a clinical syndrome that results from failure of the testes to produce physiologic levels of testosterone and a normal number of spermatozoa due to disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis.

Primary hypogonadism is caused by testicular abnormalities. Common causes of acquired primary hypogonadism in adults include mumps orchitis, sequelae of radiation treatment, antineoplastic agents or toxins, testicular trauma or torsion, and acute and chronic systemic illnesses. Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) is the most common congenital cause of primary hypogonadism and is associated with tall stature, small testes, developmental delay, and socialization difficulties.

Secondary hypogonadism reflects a hypothalamic (GnRH) and/or pituitary (LH/FSH) deficiency. There are rare congenital causes, such as Kallmann syndrome, which are associated with anosmia. Common causes of acquired hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism are hyperprolactinemia, medications, critical illness, untreated sleep disorders, obesity, liver and kidney disease, alcoholism, marijuana use, and disordered eating. Tumors, trauma, thalassemias, and infiltrative diseases that cause disruption of gonadotropin production (such as sarcoidosis and hemochromatosis) are uncommon causes.

Clinical Features

Specific symptoms of hypogonadism in the adult male include decreased morning and spontaneous erections, decreased libido, mastodynia, gynecomastia, decreased need for shaving, and/or decreased axillary and genital hair. Hot flashes, decreased bone mass, and low-trauma fractures are associated with profound and/or longstanding testosterone deficiency. Nonspecific symptoms include decreased mood, energy, concentration, muscle strength and bulk, and stamina, as well as poor sleep and memory. Infertility is more likely to occur with primary than secondary hypogonadism.

Men who develop hypogonadism before puberty have small testes and phallus and lack secondary sexual characteristics. With onset after puberty, there may be some regression of secondary sexual characteristics. A decrease in testes and/or phallus size and development of gynecomastia in adults is more likely due to a primary cause.

Evaluation

Screening men with nonspecific symptoms of hypogonadism is not recommended. In men with specific signs and symptoms, measuring an 8 AM total testosterone level is indicated. If the testosterone level is low, a second 8 AM testosterone level is measured. The diagnosis is made with two low serum testosterone measurements. Measurement of free testosterone is appropriate in men with obesity because obesity lowers SHBG, leading to a falsely low measured total testosterone level. If testosterone is low, a serum LH measurement is indicated.

An elevated LH level reflects primary hypogonadism and further evaluation should be directed toward identifying the cause.

A low or normal LH level with simultaneous low testosterone reflects secondary hypogonadism. Medications including GnRH analogues (prostate therapy treatment), gonadal steroids (such as anabolic steroid use or megestrol for appetite stimulation), high-dose glucocorticoid treatment, and chronic opiate use can all suppress gonadotropins, resulting in secondary hypogonadism. Additional evaluation includes measurement of serum prolactin and screening for hemochromatosis. Assessment for other pituitary hormone deficiencies is indicated if signs or symptoms are present. Dedicated pituitary MRI should be performed if hyperprolactinemia is present, other pituitary hormone abnormalities are identified, testosterone level is less than 150 ng/dL (5.2 nmol/L), or if there are signs or symptoms of mass effect (Figure 14).

Management

In men with biochemically proven hypogonadism, testosterone therapy can be initiated, after the etiology is determined. There are a variety of testosterone replacement preparations available (Table 41). The goal is to replace testosterone so that the measured total testosterone value is in the mid-normal range.

Clinical benefits of testosterone therapy include an increase in libido, lean muscle mass, fat free mass, bone density, and secondary sexual characteristics. Potential adverse effects include acne, impact on prostate tissue, obstructive sleep apnea, thrombophilia, and erythrocytosis (Table 42).

Testosterone therapy is only indicated for treatment of testosterone deficiency; it is not used for impaired spermatogenesis, and in fact further impairs spermatogenesis by suppressing pituitary FSH secretion. Patients should be counselled on the decreased fertility associated with exogenous testosterone therapy.

Anabolic Steroid Abuse in Men

Abuse of anabolic steroids is a serious public health concern that goes beyond the professional athlete. The prevalence of anabolic steroids use in men approaches 7%. Steroids are often purchased on the internet and dosing patterns vary. Labile mood, acne, excessive muscle bulk, and small testes may indicate anabolic steroid abuse. Reproductive side effects of anabolic steroid abuse include gynecomastia (due to peripheral conversion of testosterone to estradiol), testicular atrophy, diminished spermatogenesis and fertility, and iatrogenic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, which may be permanent. Laboratory evidence suggestive of anabolic steroid abuse includes elevated hematocrit, undetectable or low LH level, low SHBG level, and low total testosterone level with elevated testosterone precursor(s), such as androstenedione.

Testosterone Changes in the Aging Man

With aging, total testosterone and free testosterone levels in men decline and SHBG increases, which results from testicular and hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction. While serum testosterone levels decline 1% to 2% per year, most men do not become hypogonadal. Sperm production does not change significantly with age. The consequences of “andropause” are not fully elucidated, but adverse effects may include a negative impact on sexual function, muscle mass, erythropoiesis, and bone health.

The ACP suggests that testosterone therapy may be considered in cases of confirmed androgen deficiency causing sexual dysfunction. It does not suggest replacement on the basis of a low testosterone level alone or in the setting of less specific symptoms such as low energy. The decision to initiate testosterone therapy should be informed by a discussion of the many contraindications and risks of therapy. In contrast, the Endocrine Society supports treating older men with biochemically confirmed testosterone deficiency with a goal of replacement to a low-normal range of testosterone. Intramuscular testosterone is less costly than transdermal formulations and has similar efficacy and safety.

Testosterone therapy in men without biochemical evidence of deficiency has not been shown to be beneficial, and studies have shown increased risk for cardiovascular disease and death, venous thromboembolism, and prostate cancer with use of testosterone therapy.

Male Infertility

In couples with infertility, assessment of male infertility should be undertaken concurrently with female assessment. A comprehensive history should focus on potential causes of infertility: developmental history, chronic illness, infection, surgery, drugs and environmental exposures, sexual history, and prior fertility. Physical examination should focus on evidence of androgen deficiency, with careful examination of the external genitals. If testicular examination is abnormal, consider referral to a urologist. Semen analysis is the initial laboratory assessment; collection should occur after 2 to 3 days of sexual abstinence, but no longer to avoid decreased sperm motility. If semen analysis is abnormal, it should be repeated at least 2 weeks later, and if results are abnormal, referral to a reproductive endocrinologist is recommended.

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia, a benign proliferation of breast glandular tissue due to an increased action of estrogen relative to androgens, occurs in one- to two-thirds of older men. A thorough history and careful review of medications is necessary. Antiandrogen agents, such as spironolactone, cimetidine, and protease inhibitors, have a clear association with gynecomastia. Other identified causes include substance use disorder, malnutrition, cirrhosis, hypogonadism, testicular germ cell tumors, hyperthyroidism, and chronic kidney disease.

On physical examination, gynecomastia presents as a rubbery, concentric, subareolar mass. It is typically bilateral and may be tender if early in its course of development. Unilateral, nontender, and/or fixed breast masses should prompt an evaluation for breast cancer with a mammogram. Pseudogynecomastia is characterized by increased subareolar fat without glandular enlargement.

In a male presenting with painful gynecomastia, measurement of human chorionic gonadotropin, LH, morning total testosterone, and estradiol levels should be obtained if no clear cause is identified on history and physical examination.

Treatment of a specific cause of gynecomastia during the active proliferative phase may result in regression. If gynecomastia is longstanding, regression (spontaneously or with medical therapy) is unlikely due to fibrotic changes. In this scenario, plastic surgery referral may be the best option for cosmetic improvement.