Principles of Therapeutics

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Anti-Inflammatory Agents

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are effective in many rheumatologic diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), acute crystal arthropathy, systemic vasculitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), inflammatory myopathies, and autoinflammatory diseases. Advantages include rapid onset of action, ease of use, low cost, and universal availability; in many disease states, they are disease modifying and sometimes lifesaving.

Glucocorticoids have numerous adverse effects, which are more likely to occur with higher doses and longer treatment. These include osteoporosis, immunosuppression, skin fragility, glaucoma, cataracts, weight gain, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, psychomotor agitation, osteonecrosis, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression.

Patients anticipated to be taking ≥2.5-mg prednisone for ≥3 months should be risk-assessed for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and appropriately managed. Those who are at moderate or high risk for osteoporotic fractures and placed on chronic glucocorticoid therapy should begin oral bisphosphonates.

This patient at risk for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis should begin alendronate. One of the many risks and side effects of chronic glucocorticoid therapy is osteoporosis. The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) calculator defines the 10-year fracture risk for patients with T-scores in the −1.0 to −2.5 range. The FRAX calculator incorporates multiple risk factors, including sex, fracture history, femoral neck bone mineral density, glucocorticoid use, smoking, BMI, age, and alcohol intake to determine projected fracture risk. The American College of Rheumatology recommends that patients over the age of 40 years at moderate or high risk for osteoporotic fractures who are to be on at least 2.5 mg of prednisone daily for 3 months or more should begin prophylactic bisphosphonate therapy with alendronate, risedronate, or zoledronic acid. In patients on chronic glucocorticoid therapy, prophylactic bisphosphonate therapy significantly increases bone mineral density compared with placebo, and these patients also have fewer new vertebral fractures.

In patients at high risk for major osteoporotic fracture (10-year risk greater than 20% or a T score ≤−2.5 or a history of a fragility fracture) taking any dose of glucocorticoids for at least 1 month should receive prophylactic treatment (although these patients should be treated regardless of glucocorticoid therapy). Alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, or teriparatide are therapeutic options. This patient is not in the high-risk category, and teriparatide is therefore not a recommended option.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs prevent prostaglandin production by inhibiting the two isoforms of cyclooxygenase (COX), COX-1 and COX-2. COX-2 is an inducible enzyme typically expressed in inflammatory milieus, whereas COX-1 is constitutively expressed and helps maintain organismal homeostasis. Nearly all available COX inhibitors are nonselective (inhibit both isoenzymes), down-regulating prostaglandin production in inflammatory states and interfering with housekeeping functions of prostanoids (for example, renal blood flow and gut mucosal integrity maintenance) (Table 8). Nonselective COX inhibitors also inhibit thromboxane A2, inhibiting platelet function and promoting bleeding.

Although they alleviate symptoms, COX inhibitors are not disease modifying, with the apparent exception of ankylosing spondylitis. Major concerns surrounding all COX inhibitors include increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding (particularly in those already at risk) and adverse cardiovascular events; therefore, they should be prescribed at the lowest dose for the shortest time possible. COX inhibitors should generally be avoided in patients on concomitant anticoagulation.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors were developed to spare COX-1 and reduce gastrointestinal risk; although effective for this purpose, the most selective COX-2 inhibitors were found to increase the risk of cardiovascular events and were removed from the market.

NSAIDs vary with regard to kinetics, COX-1/2 selectivity, and other features, and carry somewhat different degrees of risk; having experience with several different NSAIDs is potentially beneficial in clinical practice.

Topical NSAIDs such as diclofenac are available by prescription for arthritis and pose a lower risk for systemic side effects than oral NSAIDs. They may be preferred for patients at high risk for toxicity from oral NSAIDs and/or for those ≥75 years of age. However, they are often expensive.

Colchicine

Colchicine inhibits microtubules and impairs neutrophil function. It is most commonly employed for gout and acute calcium pyrophosphate crystal arthritis (pseudogout). It is also used to treat hypersensitivity vasculitis and familial Mediterranean fever.

Gastrointestinal side effects (particularly diarrhea) are common. With overdose, severe (even fatal) myelosuppression can occur. Dosing must be adjusted for kidney disease. When given chronically, colchicine can rarely cause neuromuscular toxicity, particularly if coadministered with statin drugs. Concomitant administration of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (for example, clarithromycin) that reduce the hepatic catabolism of colchicine should be avoided. The coadministration of colchicine and clarithromycin can result in potentially fatal colchicine toxicity that manifests as rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, and pancytopenia. Colchicine is metabolized in the liver by the CYP3A4 cytochrome and should be avoided in patients taking CYP3A4 inhibitors such as clarithromycin and fluconazole. Coadministration with clarithromycin is particularly concerning, because there have been several case reports of fatal outcomes with the combination (even when taken for a short time). Once the patient recovers, however, colchicine may be reinitiated (as it is the combination of the two drugs that led to the current scenario).

Analgesics and Pain Pathway Modulators

Acetaminophen

The efficacy of acetaminophen for osteoarthritis and lower back pain has been questioned, with recent controlled trials and meta-analyses demonstrating no benefit from the drug, even at high doses (3000-4000 mg/d). The 2019 guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology and the Arthritis Foundation, however, conditionally recommend acetaminophen for knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis for patients with limited pharmacologic options.

Tramadol

Tramadol is a mixed opioid analgesic and weak serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; potential for addiction is lower than for traditional opioids, which are generally avoided in rheumatologic treatment.

Duloxetine

Duloxetine is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is FDA approved for the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain and fibromyalgia. Duloxetine provides modest pain relief for knee osteoarthritis, chronic lower back pain, and fibromyalgia. Patients must be slowly weaned off the drug when discontinuing to avoid withdrawal symptoms.

Gabapentinoids

Gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) inhibit voltage-gated calcium channels, reducing pain signaling. Pregabalin is FDA approved for fibromyalgia. Common side effects (dizziness, disequilibrium, somnolence, weight gain, peripheral edema, cognitive difficulties) may limit its utility, and discontinuation is sometimes warranted. Gabapentin also modestly improves fibromyalgia symptoms, with a similar side-effect profile. In 2019, the FDA issued a safety alert stating that serious breathing difficulties may occur in patients using gabapentin or pregabalin who have respiratory risk factors (e.g., the elderly, patients with conditions such as COPD, and users of opioid pain medications and other drugs that depress the central nervous system).

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Nonbiologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

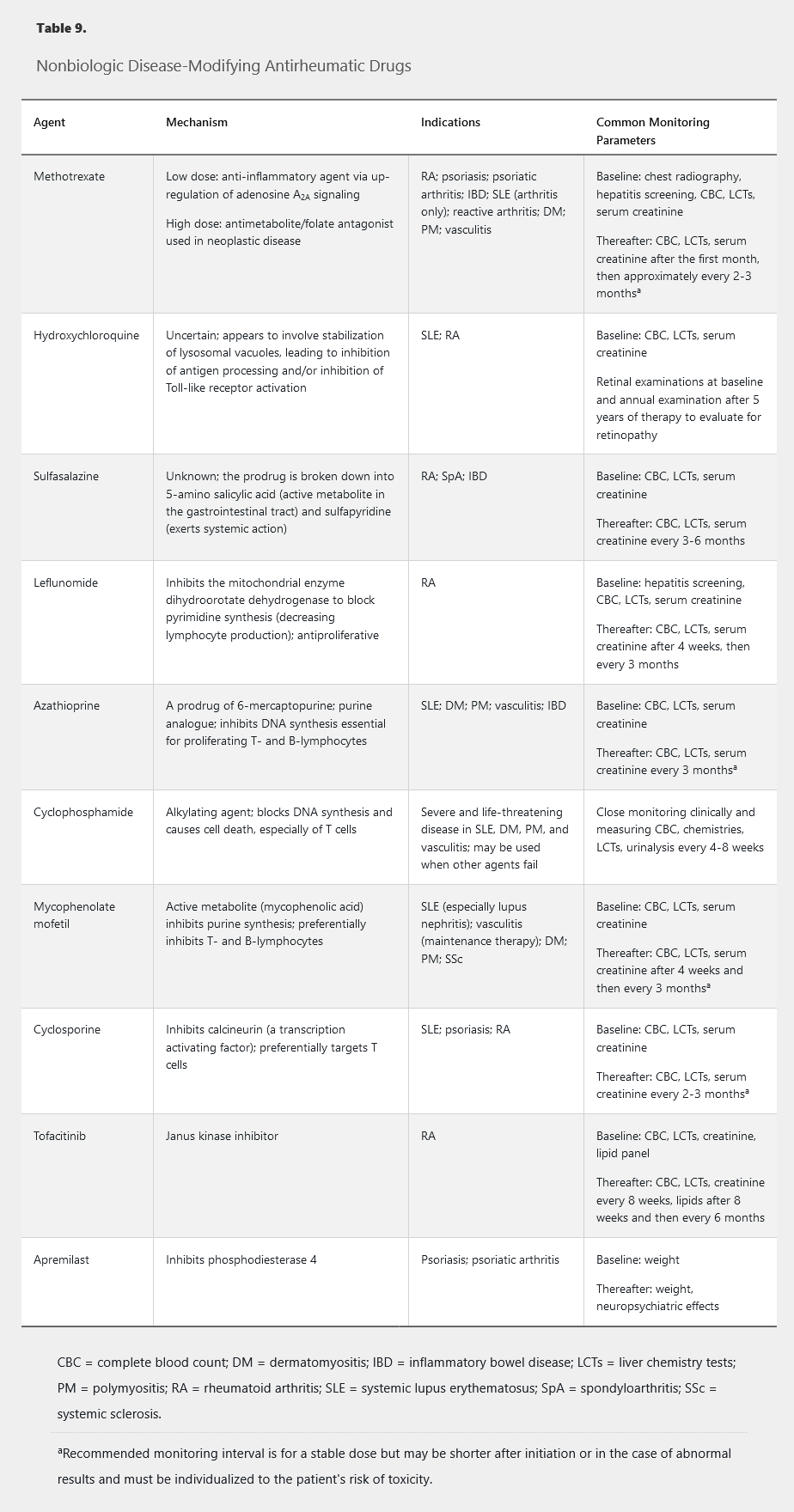

Table 9 summarizes the mechanisms of action, indications, and common monitoring parameters of various nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). See Medications and Pregnancy for information on these drugs in pregnancy.

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is a first-line medication for treating RA and other autoimmune diseases. Once-weekly dosing is generally between 10 to 25 mg and can be given orally or subcutaneously. At doses above 15 mg, parenteral administration is more reliable but much more expensive.

Potential side effects include headaches, fatigue, and nausea (particularly around the time of weekly dosing). Hepatotoxicity and cytopenias can occur (especially macrocytic anemia), and dose adjustment is required with kidney disease. Methotrexate should be avoided in patients with significant hepatic or kidney disease. Folic acid supplements minimize toxicity while preserving efficacy. Limiting alcohol intake is recommended.

Daily folic acid supplementation with 1 mg (or weekly folinic acid supplementation) has been found to reduce the mucosal, hematologic, hepatic, and gastrointestinal side effects of methotrexate. Folic acid supplementation also reduces discontinuation of methotrexate for any reason. Methotrexate blocks the cellular utilization of folic acid, and folate depletion is considered to be the cause of most of the side effects associated with methotrexate therapy. Supplementation with folic acid reduces the incidence of side effects without any loss of methotrexate efficacy in treating RA. Folic acid can be taken on the same day as methotrexate because folic acid and methotrexate enter the cell via different pathways. Folinic acid is the reduced form of folate and is typically reserved for patients who have not had a satisfactory response to folic acid. Folinic acid is considerably more expensive than folic acid, and proper timing and administration of folinic acid is complex.

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine is an immunomodulator that is widely used in SLE, in which it decreases mortality and the likelihood of developing nephritis. It is rarely sufficient as single-drug therapy for RA but is useful as an adjunctive therapy.

Sulfasalazine

Sulfasalazine is used to treat RA and nonaxial psoriatic arthritis, but use has decreased because of the relative effectiveness of methotrexate and leflunomide. It is now most frequently used as part of combination DMARD therapy for RA and in women considering pregnancy. Serious side effects include blood dyscrasias, hepatitis, and hypersensitivity reactions. Because of its benefit for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), it may constitute a useful strategy for patients with IBD-associated arthritis.

Leflunomide

Leflunomide is FDA approved for rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, with comparable efficacy to methotrexate. Patients must be monitored for hepatotoxicity and myelosuppression. Other common side effects include nausea, headaches, rash, diarrhea, and transaminitis. An uncommon side effect is peripheral neuropathy, but it is usually self-limited if the drug is discontinued. The active metabolite of leflunomide (teriflunomide) has a half-life of nearly 3 weeks; therefore, when the drug needs to be eliminated quickly, an 11-day cholestyramine washout is necessary.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is an immunosuppressant used in various inflammatory diseases. Concomitant use with xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol, febuxostat) is contraindicated. Azathioprine's primary toxicity is myelosuppression. Thiopurine methyltransferase enzyme testing allows for identification of patients with decreased or absent enzyme activity at high myelosuppression risk.

Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide is a powerful immunosuppressant with a rapid onset of action (days to weeks). It treats vasculitis, life-threatening complications of SLE, and interstitial lung disease. Cyclophosphamide has largely been displaced by newer and safer drugs for first-line treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus nephritis (rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil, respectively) but is still used in severe cases or when these agents fail. Serious potential side effects include severe immunosuppression, leukopenia, hemorrhagic cystitis, and ovarian failure, as well as long-term risk for bladder cancer, leukemia, and lymphoma.

Mycophenolate Mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil is currently the first-line agent for lupus nephritis and may be effective for systemic sclerosis and associated interstitial lung disease. Gastrointestinal side effects are common, particularly diarrhea. Myelosuppression may occur.

Calcineurin Inhibitors

Calcineurin inhibitors include cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Although cyclosporine is now rarely used in rheumatology, one of its most common side effects is hyperuricemia, and cyclosporine-induced gout is an important consideration in patients taking the drug who present with acute monoarthritis. There is currently renewed interest in tacrolimus as a possible alternative therapy for lupus nephritis.

Tofacitinib

Tofacitinib is an oral agent that inhibits Janus kinase (JAK) signaling. Tofacitinib is FDA approved for RA and has efficacy equal to biologic DMARDs. Risks include hyperlipidemia, hepatotoxicity, and leukopenia.

Apremilast

Apremilast is modestly effective for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. It does not cause immunosuppression or myelosuppression. However, apremilast is less efficacious than biologic DMARDs and has a slow onset of action, and its effect on progression of erosive damage is unknown. Adverse events include gastrointestinal side effects (mainly nausea and diarrhea) and weight loss. It should be used with caution in patients with a history of depression.

Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Biologic DMARDs are highly specific, parenterally administered, protein-based agents with extracellular targets (specific proinflammatory cytokines, cytokine receptors, or clusters of differentiation cell surface molecules on immune cells; Figure 1). The end of the generic name of a biologic agent indicates what type of molecule it is: -mab indicates monoclonal antibody; -kin indicates an interleukin-type substance; -ra is for a receptor antagonist; and -cept is for receptor molecules.

Table 10 and Table 11 summarize the structures, targets, indications, and common monitoring parameters of various biologic DMARDs. See Medications and Pregnancy for information on these drugs in pregnancy. Biologic DMARDs increase the risk for infection to variable degrees. Targeted screening is therefore necessary before initiation (see Vaccination and Screening in Immunosuppression).

The cost of biologic agents is significant and may be a barrier to access.

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors are large protein-based molecules that require parenteral administration (see Table 10). They are widely used for treating RA, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis, and are also approved for several nonrheumatologic diseases.

TNF-α inhibitors are generally well tolerated, with increased risk for infection the primary safety concern. They pose a particularly high risk for reactivation of tuberculosis, so all patients being considered for TNF-α inhibitor therapy need to be screened and receive appropriate prophylaxis. TNF-α inhibitors do not appear to increase the risk of new cancers, aside from nonmelanoma and possibly melanoma skin cancer; the risk for malignant recurrence is unclear. These agents may also exacerbate heart failure and rarely provoke a demyelinating condition. Over time, TNF-α inhibitors may often lose efficacy owing to formation of anti-drug antibodies.

Other Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Multiple biologic DMARDs with additional extracellular and cell-surface targets have been approved by the FDA in the past decade. Most of these agents are started after one or two TNF-α inhibitors have failed. See Table 11 for more information.

Biosimilars

Biosimilar agents are “copycat” versions of brand-name biologic medications. The drugs are not exact replicas (hence the term “biosimilar” rather than “generic”); therefore, they must go through phase III testing to garner regulatory approval. In 2016, the FDA approved three biosimilar anti-TNF agents.

Urate-Lowering Therapy

Allopurinol

Allopurinol is the most commonly used urate-lowering agent. It competitively inhibits the enzyme xanthine oxidase, blocking the conversion of hypoxanthine (a breakdown product of purines) to uric acid. Allopurinol is metabolized to oxypurinol, which also inhibits xanthine oxidase. Allopurinol is FDA approved for doses up to 800 mg/d. According to the American College of Rheumatology, allopurinol should be initiated at 100 mg/d and titrated in 100-mg increments as needed, and for those with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease, allopurinol should be initiated at 50 mg/d and titrated in 50-mg increments as needed.

The biggest risk the drug poses is DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome, a rare reaction that usually occurs in the presence of chronic kidney disease and diuretic use and has a high mortality rate (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology). A recently discovered DRESS risk factor is the HLA-B_5801 allele, which is more common in Black persons and persons of Southeast Asian descent (Han Chinese, Thai, and Korean). Screening for HLA-B_5801 in these populations is conditionally recommended before initiating therapy with allopurinol. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors cannot be coadministered with purine analogues (such as azathioprine).

Febuxostat

Febuxostat is a noncompetitive xanthine oxidase inhibitor. As with allopurinol, transaminitis rarely occurs, and liver enzymes should be monitored. Concomitant use with purine analogues is contraindicated. Incidence of DRESS syndrome is rare. In February 2019, the FDA mandated a boxed warning for febuxostat regarding the increased risk for cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality with the drug. The FDA has also limited the approved use of febuxostat for patients who are unresponsive to or cannot tolerate allopurinol.

Uricosuric Agents

Probenecid is an organic acid transport inhibitor that decreases renal reuptake of uric acid. Probenecid is uncommonly used because of limited efficacy, as well as inconvenience and limitations on use.

Lesinurad, a more effective uricosuric agent, was discontinued by its manufacturer in 2019 for business reasons.

Pegloticase

Unlike most other mammals, humans lack a functioning uricase to break down uric acid. Pegloticase is a recombinant, nonhuman, infusible pegylated uricase that is highly effective at lowering serum urate. Pegloticase is reserved for severe and/or refractory gout. Because of its extreme potency, mobilization flares of gout are common, and prophylaxis against acute gouty attacks is required. Pegloticase is administered intravenously every 2 weeks; if the pre-infusion serum urate increases to more than 6.0 mg/dL (0.35 mmol/L) on two occasions, it is likely that antibodies have formed, and the drug should be discontinued to prevent infusion reactions.

Key Points

- Allopurinol is the most commonly used urate-lowering agent; the biggest risk the drug poses is DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome, which has a high mortality rate.

- Concomitant use of xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol or febuxostat) with purine analogues is contraindicated.

Medications and Pregnancy

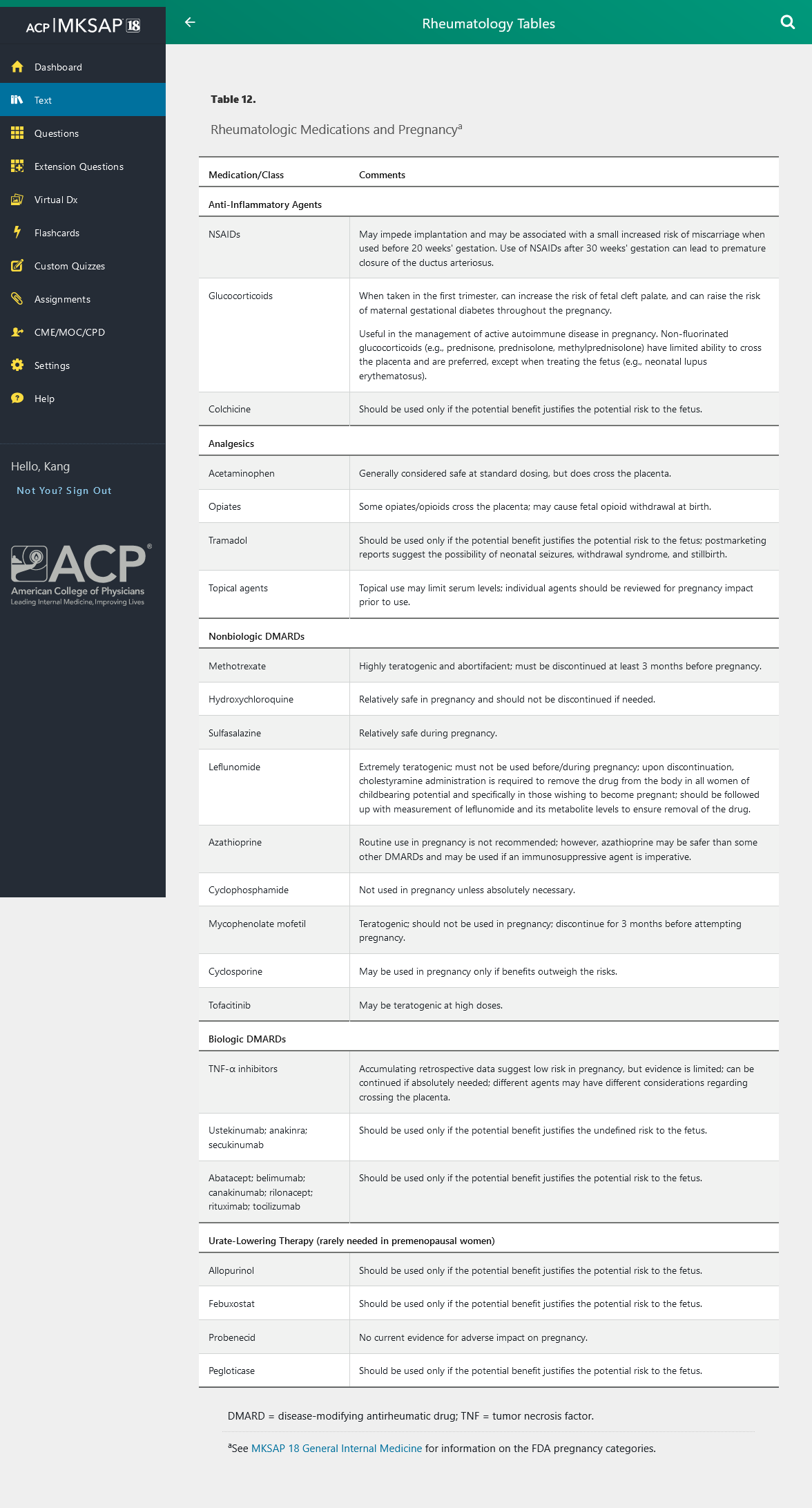

Some rheumatologic medications can have adverse effects on pregnancy. See Table 12 for a discussion of these agents and their relative risks.

Vaccination and Screening in Immunosuppression

Patients should be updated with vaccinations before initiating biologic DMARD regimens. Vaccine response may be diminished once on treatment, and patients on some immunosuppressants (including all biologic DMARDs and tofacitinib) should not receive live attenuated vaccines (such as for herpes zoster, live attenuated influenza, and yellow fever) because of risk for viral activity in an immunocompromised host. Patients already receiving DMARD therapy, including biologic DMARDs, should receive any nonlive vaccines that are indicated as per standard of care (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for more information), but these vaccines should ideally be administered before initiation of biological therapy. Patients receiving traditional oral DMARDs (for example, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and sulfasalazine) may receive any and all vaccines as needed.

Before initiating immunosuppressive therapy, the following screening is recommended:

- Tuberculosis screening with tuberculin skin testing or interferon-γ release assay, particularly for patients initiating biologic DMARDs

- Hepatitis B and C serologies (for biologic DMARDs and drugs that can cause hepatotoxicity)

- HIV screening

Patients with latent or active tuberculosis, active hepatitis B, or untreated HIV infection require initiation of appropriate therapy before initiating immunosuppression. Repeat screening for tuberculosis should be performed annually if there are risk factors for ongoing tuberculosis exposure.

Nonpharmacologic and Nontraditional Management

Because rheumatologic diseases frequently affect the musculoskeletal system, nonpharmacologic measures are often employed to address pain not eliminated by medications. These measures include physical therapy, occupational therapy, surgery, weight reduction, psychosocial support, and self-management programs. Many patients turn to complementary and alternative medicine as adjuncts to traditional medical interventions.

Physical and Occupational Therapy

The physical therapist can aid the primary care provider in assessing a patient's aerobic fitness and conditioning as well as the patient's ability to carry out activities of daily living. Pain and functional limitation can be addressed through manual therapy, assistive devices, joint protection techniques, and thermal treatments. A targeted exercise program can be initiated, and adapting the program for home use is critical. Tendinitis, bursitis, many forms of arthritis, and chronic soft tissue pain due to overuse, injury, and chronic pain syndromes (such as fibromyalgia) are among the diagnoses appropriate for physical therapy referral.

Occupational therapists assess upper extremity functioning, including the ability to perform self-care and job-related tasks. Braces and splints may be provided for painful or unstable joints. An ergonomic evaluation of the workstation may accompany instruction in improved body mechanics and avoidance of repetitive trauma.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Nontraditional options for symptom management are employed by about one third of patients overall and up to 90% of patients with chronic pain, including arthritis and rheumatologic diseases. Commonly used over-the-counter supplements include fish oil, vitamins, glucosamine, and chondroitin. Providers should ask about supplement use because patients rarely volunteer this information. Significant drug interactions may occur; for example, some herbal preparations can interact with anticoagulants.

Mind-body interventions such as tai chi, meditation, and yoga can improve psychological well-being, strength, balance, and pain level. Chiropractic and osteopathic manipulation as well as massage remain popular. Randomized controlled trials support the use of tai chi for arthritis; smaller trials suggest benefit from meditation techniques, yoga, massage, and manipulative medicine for various musculoskeletal problems.

Role of Surgery

Surgical procedures such as carpal tunnel release or rotator cuff tendon repair can address conditions that arise from repetitive trauma, injury, and degenerative changes in the soft tissue. Synovectomy of inflammatory pannus is occasionally employed when a single or limited number of joints in patients with RA do not respond to medications. Total joint arthroplasty, particularly of the knee or hip, can reduce or eliminate pain and restore function in patients with an inadequate response to medication and physical or occupational therapy.