Perioperative

-

related: Medicine

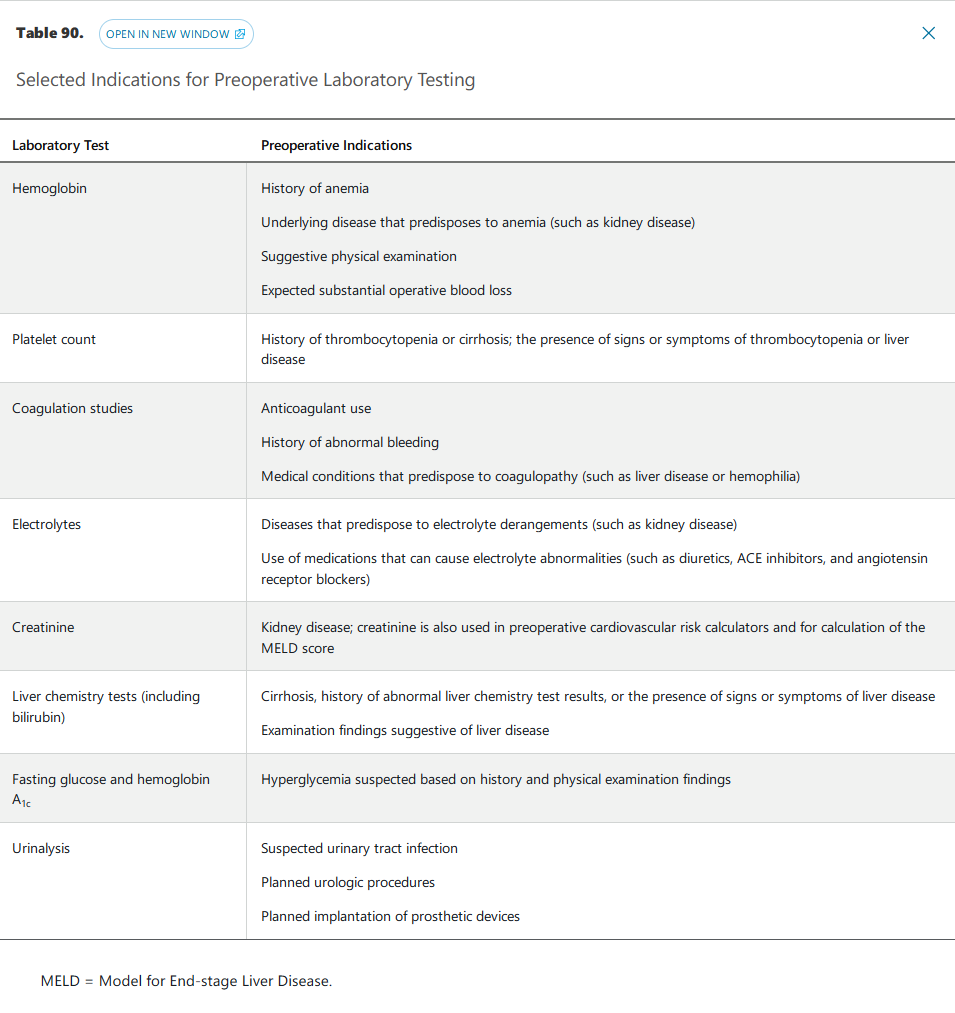

Preoperative Laboratory Testing

Perioperative Medication Management

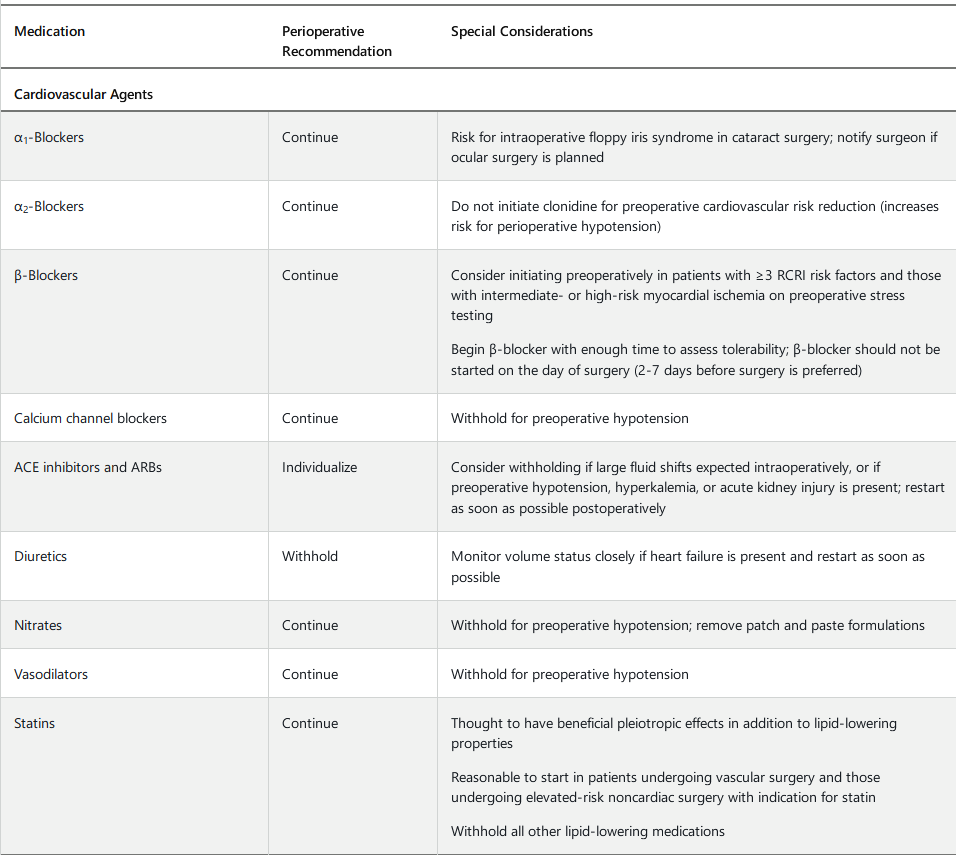

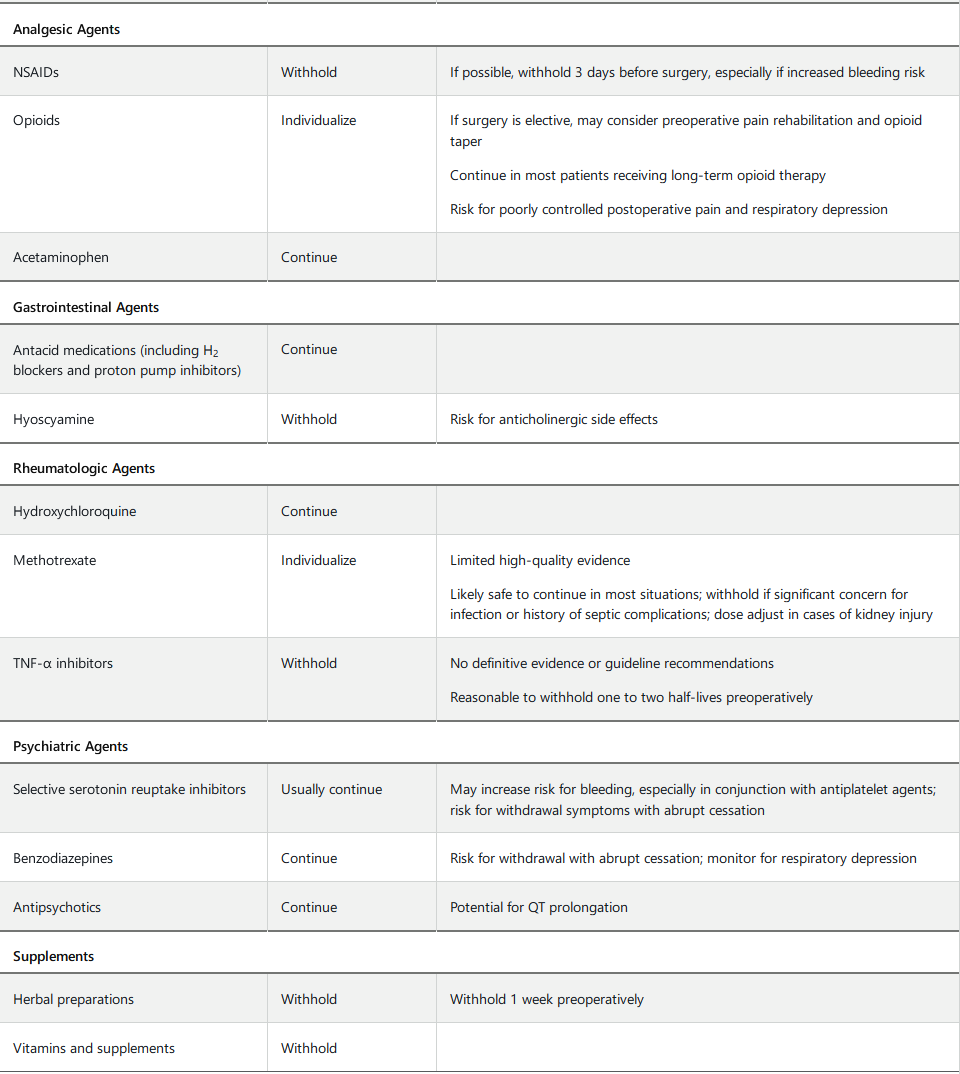

Perioperative medication management begins with eliciting a complete preoperative medication history, including herbal preparations, supplements, and over-the-counter medications. Careful medication reconciliation should be performed to rectify any discrepancies and to prevent medication errors.

There is a paucity of high-quality evidence to guide perioperative medication management. Most medications are tolerated throughout the perioperative period, with some important exceptions. Table 91 provides perioperative recommendations for medications with potential surgery-related risk. Patients should be provided with clear instructions on which medications to withhold preoperatively and for what duration.

Postoperative Care

Promotion of patient mobilization, use of lung expansion modalities (see Perioperative Risk-Reduction Strategies), improvement in patient nutrition, and enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs may all decrease the likelihood of postoperative complications. Early mobilization and physical therapy (as necessary) are important components of the postoperative care plan and may decrease the probability of postoperative pneumonia and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Malnutrition is a risk factor for perioperative morbidity, including infection and poor wound healing, and several nutrition risk stratification tools are available to identify patients at risk for postoperative complications related to malnutrition. The Subjective Global Assessment of Nutritional Status tool incorporates history of calorie intake and physical examination findings, whereas the Nutritional Risk Screening Tool relies on age, BMI and weight loss, and severity of the current medical condition. Serum protein markers, including albumin and prealbumin, are also predictive of postoperative complications. Loss of 15% of body weight over 6 months and a serum albumin level less than 3.0 g/dL (30 g/L) are the most predictive factors of poor surgical outcomes related to malnutrition. Notably, increased enteral calorie intake is effective in reducing postoperative complications.

ERAS programs use evidence-based protocols to standardize care, improve outcomes, and reduce costs in postoperative patients. Best studied in patients undergoing colorectal surgery, ERAS interventions include optimization of nutritional status, physical conditioning, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco, postoperative mobilization, and early removal of urinary catheters. ERAS programs have been demonstrated to decrease length of hospital stay and result in earlier mobilization and return of bowel function in colorectal surgery populations. They are currently being implemented and studied in other surgical populations.

Common complications in the postoperative setting include postoperative urinary retention (POUR), postoperative ileus, and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). POUR is characterized by incomplete bladder emptying after surgery, resulting in increased postvoid residual urine volume. Risk factors include type of surgery (incontinence and anorectal surgery, hernia repair, joint arthroplasty), longer surgery, use of regional anesthesia, administration of more than 750 mL of intraoperative fluids, use of certain postoperative medications (opioids, anticholinergic agents), older age, constipation, pelvic organ prolapse, neurologic disease, history of urinary retention, and history of pelvic surgery. POUR is a urologic emergency. Reversible causes of POUR, such as medication use, should be addressed. In patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia, α2-blockers should be continued, whereas medications with associated anticholinergic effects, such as oxybutynin, should be withheld. Early removal of indwelling catheters and voiding trials are recommended. For patients in whom a voiding trial is unsuccessful, clean intermittent catheterization is indicated. Urinary tract obstruction should be excluded if POUR is persistent.

Postoperative ileus, or gastrointestinal hypomotility after surgery, is associated with increased length of hospital stay. Ileus is often a physiologic response related to sympathetic nervous system activation, although it can also be caused by activation of inflammatory mediators or the use of medications, such as anesthetics and opioids. Risk factors for the development of postoperative ileus include abdominal and pelvic surgery, open surgical technique, and the presence of other postoperative complications, such as pneumonia. Treatment of ileus includes minimization of postoperative opioids, adequate hydration, bowel rest, electrolyte repletion, postoperative ambulation, and use of chewing gum. Preventive measures for ileus include an appropriate postoperative bowel regimen, which may comprise fiber, stool softeners, osmotic laxatives, and stimulant laxatives. Few data from well-designed clinical trials are available to guide therapy for prolonged postoperative ileus, typically defined as ileus lasting longer than 3 to 5 days. In these patients, it is important to distinguish postoperative ileus from mechanical bowel obstruction.

The prevention and treatment of PONV, a common postoperative event that results in significant patient distress, require a multifaceted approach that involves identifying at-risk patients, reducing baseline risk factors, providing prophylaxis, and treating symptoms. Risk factors for PONV include female sex; young age; nonsmoking status; and use of general anesthesia, postoperative opioids, or volatile anesthetics. Although many risk-mitigation strategies include intraoperative and immediate postoperative care, the internist plays an important role in ensuring adequate postoperative hydration, minimizing the use of opioids, and providing pharmacologic antiemetic therapy.

Cardiovascular Perioperative Management

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment

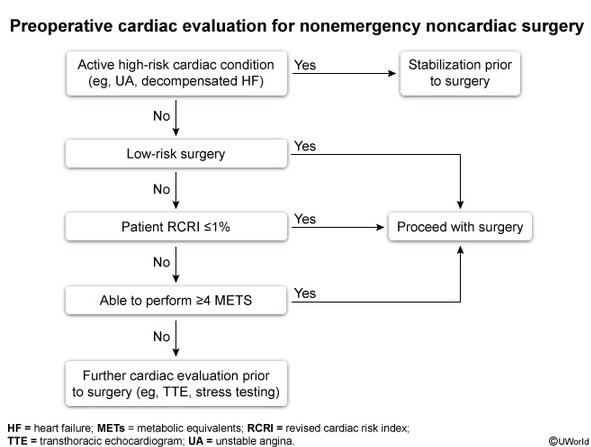

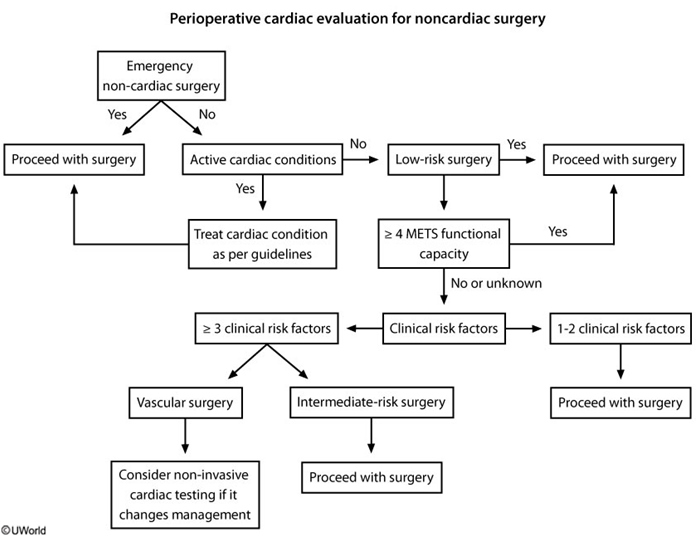

Preoperative cardiac evaluation entails assessment of patient-specific risk, surgery-specific risk, and urgency of surgery (emergent, urgent, or time sensitive). The approach recommended by the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery is presented in Figure 29.

Risk calculators, including the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (Table 92) and American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest calculator (https://riskcalculator.facs.org/RiskCalculator), can be used to determine the risk for a perioperative major adverse cardiac event (MACE). Both risk calculators incorporate patient- and surgery-specific risk factors.

Patients with low risk (<1% risk of perioperative MACE) may proceed to surgery without preoperative cardiac stress testing, whereas patients with elevated risk (≥1% risk for perioperative MACE) should undergo assessment of functional capacity. Metabolic equivalents (METs) are used to represent the patient's functional capacity based on the intensity of activity able to be performed. If the patient's functional capacity exceeds 4 METs, the patient may proceed to surgery without further testing. Examples of activities that require 4 METs include walking 4 miles per hour on a flat surface; climbing one to two flights of stairs without stopping; or performing vigorous housework, such as vacuuming. Cardiac stress testing should be considered in patients at elevated risk for MACE with a functional capacity of less than 4 METs or if functional capacity cannot be determined, but only if the results of stress testing will change perioperative management.

Preoperative electrocardiography (ECG) is reasonable in patients with known coronary artery disease, arrhythmia, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or structural heart disease undergoing moderate- to high-risk surgeries. Preoperative ECG may be considered for other asymptomatic patients except those undergoing low-risk procedures. ECG may not alter preoperative decision making, but it provides a useful baseline to guide postoperative management in the event of complications.

Echocardiography to evaluate left ventricular function should not be routinely performed preoperatively. Echocardiography is recommended in certain clinical scenarios, such as in the presence of dyspnea of unknown origin, heart failure with worsening dyspnea or overall change in clinical status, known left ventricular dysfunction without echocardiographic assessment in the last year, and known or suspected moderate to severe valvular stenosis or regurgitation without echocardiographic assessment in the last year or with a change in clinical status.

Cardiovascular Risk Management

Coronary Artery Disease

Patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) should not undergo routine coronary angiography or revascularization exclusively to reduce perioperative events. These procedures should be reserved for patients with recognized indications based on existing clinical practice guidelines. In patients who meet the criteria for intervention and in whom noncardiac surgery is time sensitive, balloon angioplasty or bare metal stent implantation should be considered over use of a drug-eluting stent. Elective noncardiac surgery should be delayed 14 days after balloon angioplasty, 30 days after bare metal stent implantation, and optimally 6 to 12 months after drug-eluting stent placement. However, if the risk of surgical delay outweighs the risk for ischemia and stent thrombosis, surgery may be considered 90 days after drug-eluting stent placement.

Patients taking β-blockers, statins, and many antihypertensive medications should continue these medications throughout the perioperative period, unless prohibited by hypotension. In hypotensive patients, dosage reduction is preferred to β-blocker discontinuation. There are also circumstances in which β-blocker or statin therapy should be initiated preoperatively (see Table 91). Postoperative β-blocker administration should be guided by clinical circumstances.

The ACC/AHA perioperative evaluation and management guideline does not recommend routinely obtaining postoperative troponin levels and an ECG in asymptomatic patients. However, these tests are recommended in patients with signs or symptoms of myocardial ischemia, which often presents atypically in the postoperative period (including as delirium in the elderly, hyperglycemia, and blood pressure fluctuations).

Heart Failure

Medical management of decompensated heart failure should be optimized before surgery and may involve diuresis, fluid restriction, and medication adjustments (see MKSAP 18 Cardiovascular Medicine).

Cardiac Arrhythmias

Risk management strategies for patients with a cardiac arrhythmia who are undergoing surgery include continuation of antiarrhythmic medications and, for some patients, continuous cardiac monitoring.

Patients with atrial fibrillation are at risk for rapid ventricular rate due to surgical stress, fluid shifts, and postoperative pain. Maintaining euvolemia, optimizing postoperative pain management, and controlling rates with medications are all appropriate strategies in stable patients. Hemodynamically unstable patients should undergo direct-current cardioversion.

A cardiologist should be consulted in patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator who are undergoing surgery. Patients in whom a device has been deactivated for surgery should undergo continuous cardiac monitoring until the device is reprogrammed.

Valvular Heart Disease

The ACC/AHA guideline states that it is reasonable to perform elevated-risk elective noncardiac surgery in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, or aortic regurgitation with preserved left ventricular function. In patients who are candidates for valvular intervention due to symptoms or severity of disease, valvular intervention should be performed before elective noncardiac surgery.

Pulmonary Hypertension

Preoperative evaluation by a pulmonary hypertension specialist is advised for patients with pulmonary hypertension with high-risk features, including group 1 pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary arterial hypertension), pulmonary arterial systolic pressure greater than 70 mm Hg, moderate or severe right ventricular systolic dysfunction, and New York Heart Association functional class III or IV symptoms attributable to pulmonary hypertension. Patients with pulmonary hypertension undergoing noncardiac surgery should be continued on pulmonary vascular targeted therapies, such as phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors.

Primary Hypertension

In patients with hypertension, urgent blood pressure lowering is not mandatory preoperatively unless there is evidence of end-organ dysfunction, in which case surgery should be delayed and blood pressure treated. Deferral of surgery may also be considered in patients with a systolic blood pressure of 180 mm Hg or higher or diastolic blood pressure of 110 mm Hg or higher. Moderate preoperative hypertension has not been linked to adverse perioperative outcomes, although evidence is lacking regarding a specific blood pressure threshold. The perioperative use of specific antihypertensive agents is outlined in Table 91.

Pulmonary Perioperative Management

Perioperative pulmonary complications include pneumonia, respiratory failure, and exacerbation of underlying lung disease. Pulmonary perioperative management involves pulmonary risk assessment, including screening for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), assessment of any underlying lung disease with optimization of treatment, and optimization of perioperative risk-reduction strategies.

Pulmonary Risk Assessment

Pulmonary risk factors can be categorized as patient-related risk factors or procedure-related risk factors (Table 93). Obesity and well-controlled asthma have not been shown to be independently associated with perioperative pulmonary complications. Risk calculators that include many of the important risk factors as well as other predictors, such as low oxygen saturation and the presence of preoperative sepsis, are available to help determine postoperative risk for respiratory failure, pneumonia, and overall pulmonary complications. The Postoperative Respiratory Failure Risk Calculator is available at www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/prf-risk-calculator, and the Postoperative Pneumonia Risk Calculator is available at www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/postoperative-pneumonia-risk-calculator. These calculators do not consider important pulmonary comorbid conditions, such as COPD and OSA, but they are useful in planning for surgery and establishing informed consent.

Spirometry is not useful for predicting risk and should not be routinely ordered for preoperative evaluation, including in patients with COPD. Furthermore, evidence does not support a spirometric threshold below which the risk of surgery is unacceptable. Spirometry is indicated in patients undergoing lung resection, however, to help predict postoperative lung function. Chest radiography is not required in most patients but is indicated in patients with signs or symptoms of pulmonary disease and in patients with underlying cardiac or pulmonary disease and new or unstable symptoms.

All patients should be screened for OSA, which is associated with adverse perioperative outcomes, including cardiac events, pulmonary complications, and ICU admissions. A commonly used screening tool for OSA is the STOP-BANG score (Table 94). In high-risk patients undergoing elective surgery, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends further evaluation with polysomnography.

Assessment of Underlying Lung Disease

COPD is the most commonly identified risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications. Patients should be screened preoperatively for signs and symptoms of COPD exacerbation and instructed to take prescribed inhaled medications on the morning of surgery. In patients with an exacerbation, surgery should be postponed, and treatment should be initiated.

Perioperative Risk-Reduction Strategies

Risk for pulmonary complications should be mitigated with perioperative risk-reduction interventions, including preoperative initiation of lung expansion maneuvers (deep breathing exercises and incentive spirometry), limiting use of nasogastric tubes in abdominal surgery for nausea or abdominal distention, and aspiration precautions. A recent multicenter randomized trial demonstrated that a 30-minute preoperative education and breathing exercise training session can reduce postoperative pulmonary complication rates by 50%. Smoking cessation has been shown to reduce pulmonary risk and should be encouraged as far in advance of surgery as possible. Patients with pulmonary disease should continue outpatient medications. Perioperative management should also include goal-directed fluid management and consideration of lung-protective ventilation strategies.

In patients diagnosed with OSA, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) should be initiated preoperatively. Patients at high risk for OSA undergoing nonelective surgery should be placed on continuous pulse oximetry and monitored for oxygen desaturation, apneas, reduced respiration rate, and oversedation in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU); patients with recurrent respiratory events in the PACU benefit from additional monitoring postoperatively. All patients with known OSA should bring their CPAP device to the hospital for use in the perioperative period.

Hematologic Perioperative Management

Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) antithrombotic guideline provides recommendations for VTE prophylaxis for both orthopedic and nonorthopedic surgery populations (Table 95). In patients undergoing general surgery or abdominal-pelvic surgery, the ACCP recommends using the Caprini score to estimate the patient's risk for postoperative thrombosis (Table 96).

Hip fracture surgery, total knee arthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty pose a high risk for VTE, and both mechanical (nonpharmacologic) and pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis are recommended. Mechanical prophylaxis is provided with an intermittent pneumatic compression device. For pharmacologic prophylaxis, the ACCP recommends low-molecular-weight heparin in preference to other pharmacologic agents. The minimum recommended duration of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery is 10 to 14 days; however, in patients without increased bleeding risk, extended-duration postoperative prophylaxis (up to 35 days) is preferred over shorter-duration prophylaxis. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices and pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis are recommended during the entire hospital stay. If bleeding risk is especially high, mechanical prophylaxis is recommended over no prophylaxis. In patients who decline or are unable to tolerate low-molecular-weight heparin, the ACCP recommends apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or a vitamin K antagonist over alternate forms of prophylaxis.

Multiple guidelines recommend against the routine placement of inferior vena cava filters for VTE prophylaxis. Routine surveillance for VTE with venous compression ultrasonography is also not recommended in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, general surgery, abdominal-pelvic surgery, and trauma surgery.

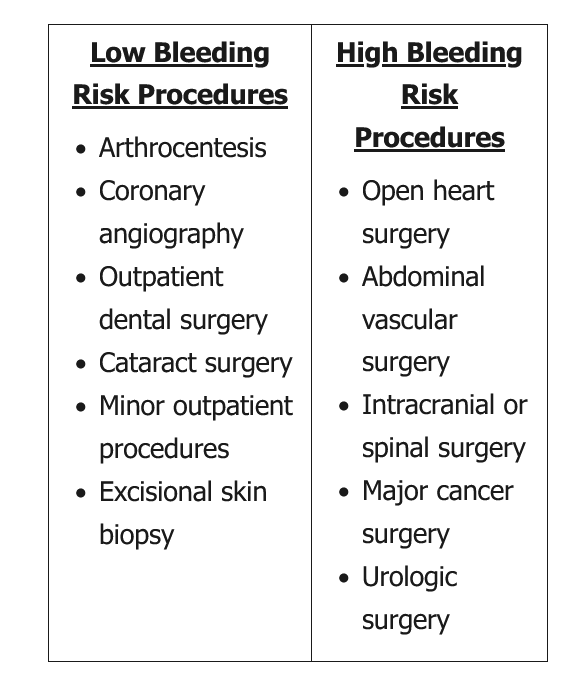

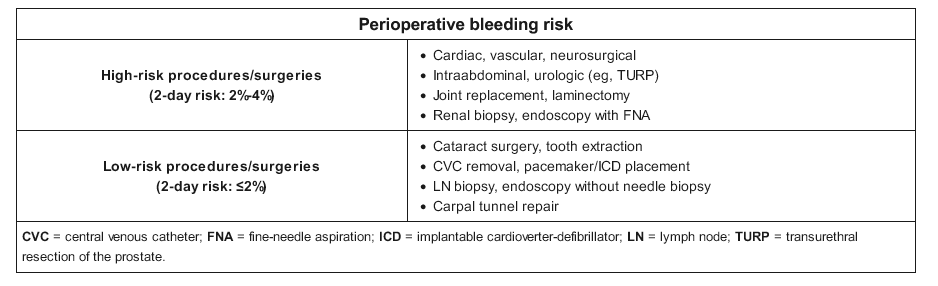

Perioperative Management of Anticoagulant Therapy

Anticoagulant therapy increases the risk for perioperative hemorrhage and should be discontinued in most patients before surgery. Minor surgery, including dental extractions and minor skin surgery, can be completed while a patient is anticoagulated. Vitamin K antagonist (warfarin) therapy may also be continued in some patients undergoing cardiac device implantation, although the best approach to these procedures in patients receiving non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs), including direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors, is unclear. In any case, collaboration with the surgeon or proceduralist is crucial to ensure that it is safe for the patient to remain anticoagulated. When it is necessary to discontinue anticoagulation, vitamin K antagonists should be discontinued at least 5 days before surgery; most procedures can be safely performed with an INR of less than 1.5. The duration for which NOACs are discontinued before surgery depends on the bleeding risk of the procedure, the patient's kidney function, and the medication half-life; generally, NOACs can be stopped 2 to 3 days preoperatively because of their shorter half-lives.

Bridging anticoagulation is the administration of therapeutic doses of short-acting parenteral therapy, usually heparin, when oral anticoagulant therapy is being withheld during the perioperative period in patients with elevated thrombotic risk. Bridging is most commonly indicated in patients taking vitamin K antagonists. It is not indicated in patients taking NOACs because of the rapid onset and short half-life associated with these drugs, but it may be needed when patients are unable to take oral medications for an extended time after surgery, such as with gastrointestinal surgery.

Postprocedural management of anticoagulation is based on thrombotic and bleeding risk, and close collaboration with the surgeon is essential. In patients taking a vitamin K antagonist, bridging anticoagulation may be deferred if thrombotic risk is low; the first dose of a vitamin K antagonist is typically administered 12 to 24 hours after surgery. If bridging is needed and the bleeding risk is low, bridging anticoagulation may be started as soon as 24 hours after the procedure; in the case of high bleeding risk, initiation of bridging anticoagulation is delayed 48 to 72 hours or possibly longer. Postoperative timing of NOAC reinstitution depends on bleeding risk, as NOACs reach therapeutic levels in 1 to 3 hours, at which point the patient is presumed to be fully anticoagulated. NOACs may be resumed once adequate hemostasis is ensured, usually 48 to 72 hours after surgery.

Because of the risk for spinal epidural hematoma, anticoagulant use with concomitant neuraxial (spinal and epidural) anesthesia should be avoided.

Atrial Fibrillation

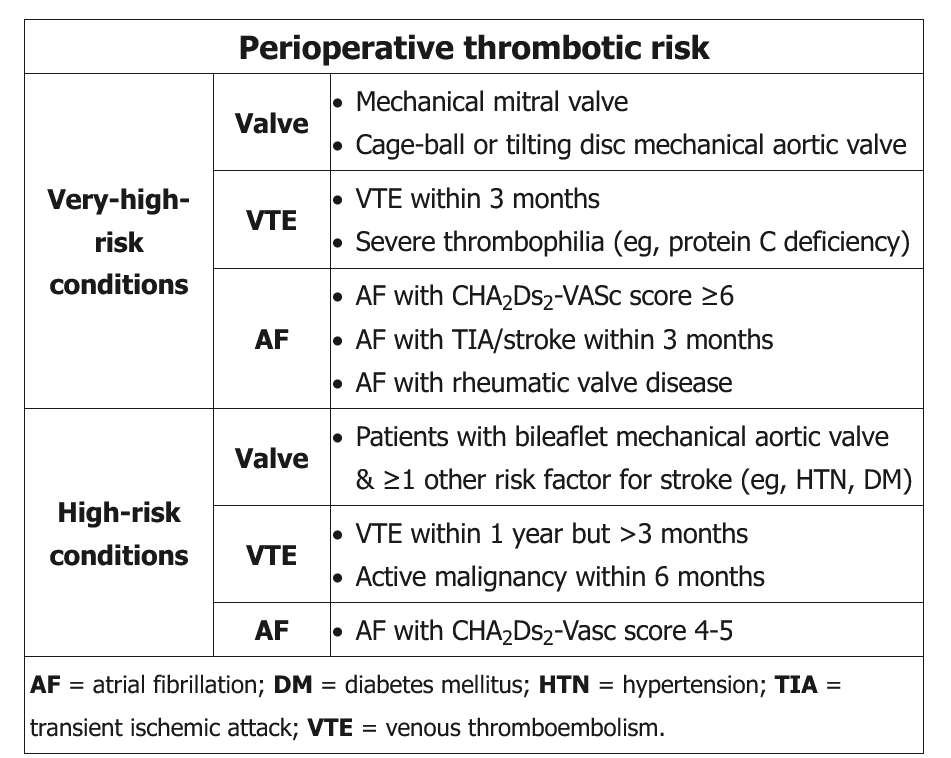

The decision to initiate bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation is based on bleeding risk and thrombotic risk. Procedures with an intermediate or high risk for bleeding almost always require interruption of anticoagulation.

The landmark BRIDGE trial has shifted clinical practice toward a more conservative approach to bridging anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. This randomized controlled trial determined bleeding and thrombotic outcomes in patients who received bridging anticoagulation compared with those who did not. An increased risk for bleeding was identified in patients who received bridging anticoagulation, and those who received no bridging anticoagulation did not demonstrate an increased risk for thrombosis.

According to recent AHA/ACC and ACCP guidelines, preoperative bridging is not recommended in patients with atrial fibrillation taking warfarin without a mechanical valve or high risk for thromboembolism. Examples of high-risk conditions for thromboembolism include ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, or systemic embolism within the past 3 months.

Prosthetic Heart Valves and Venous Thromboembolic Disease

In patients receiving warfarin anticoagulant therapy for a mechanical prosthetic heart valve, continuation of anticoagulation is recommended when the surgical procedure is minor and bleeding can be managed. In patients undergoing surgery with a higher risk for bleeding, the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline on valvular heart disease suggests that bridging should be considered on an individualized basis in patients with a mechanical mitral valve, a mechanical aortic valve with thromboembolic risk factors, or an older-generation mechanical aortic valve. Bridging is not necessary in patients with a bileaflet mechanical aortic valve and no other risk factors for thrombosis. The ACCP provides similar recommendations for bridging anticoagulation in patients with prosthetic heart valves (Table 99).

Recommendations for bridging anticoagulation in those with a history of venous thromboembolism, including patients with thrombophilias, are included in Table 100.

Perioperative Management of Antiplatelet Medications

The perioperative management of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), comprising aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel, ticagrelor, or prasugrel), in patients with CAD depends on the presence of a bare metal or drug-eluting coronary stent, time since stent placement, and, to some degree, the indication for DAPT (stable ischemic heart disease [SIHD] or acute coronary syndrome [ACS] within the last year).

In patients who have a stent placed for SIHD, DAPT should be continued uninterrupted for at least 30 days after bare metal stent placement and a minimum of 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement. Elective surgery should be postponed during these time frames. However, if the risk of surgical delay exceeds the risk for stent thrombosis, discontinuation of the P2Y12 inhibitor can be considered after a minimum of 3 months in patients with a drug-eluting stent. Aspirin should be continued if at all possible, and DAPT should be restarted as soon as bleeding risk has sufficiency diminished.

In patients with recent ACS, the ACC and AHA recommend continuing DAPT for at least 1 year regardless of whether the ACS was managed with medical therapy or coronary stent placement. If surgery must be performed within this time frame, DAPT should optimally be maintained for a minimum of 6 months. If more than 3 months have passed and the patient cannot be continued on DAPT because of bleeding risk, proceeding with surgery can be considered if the risk of surgical delay is greater than the risk for stent thrombosis.

In patients with recent percutaneous coronary intervention with stent placement for ACS in whom surgery mandates discontinuation of DAPT, aspirin should be continued. In patients with recent ACS treated medically who must undergo surgery for which DAPT must be discontinued, it is similarly reasonable to continue aspirin when the risk for cardiac events outweighs the risk for bleeding.

In most patients receiving long-term aspirin monotherapy for both primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events (in the absence of a coronary stent), aspirin should be discontinued at least 5 days before surgery and restarted postoperatively once bleeding risk has decreased. This recommendation is based on the POISE-2 trial, which found that continued perioperative aspirin resulted in increased bleeding without a decrease in cardiac events.

Perioperative Management of Anemia, Coagulopathies, and Thrombocytopenia

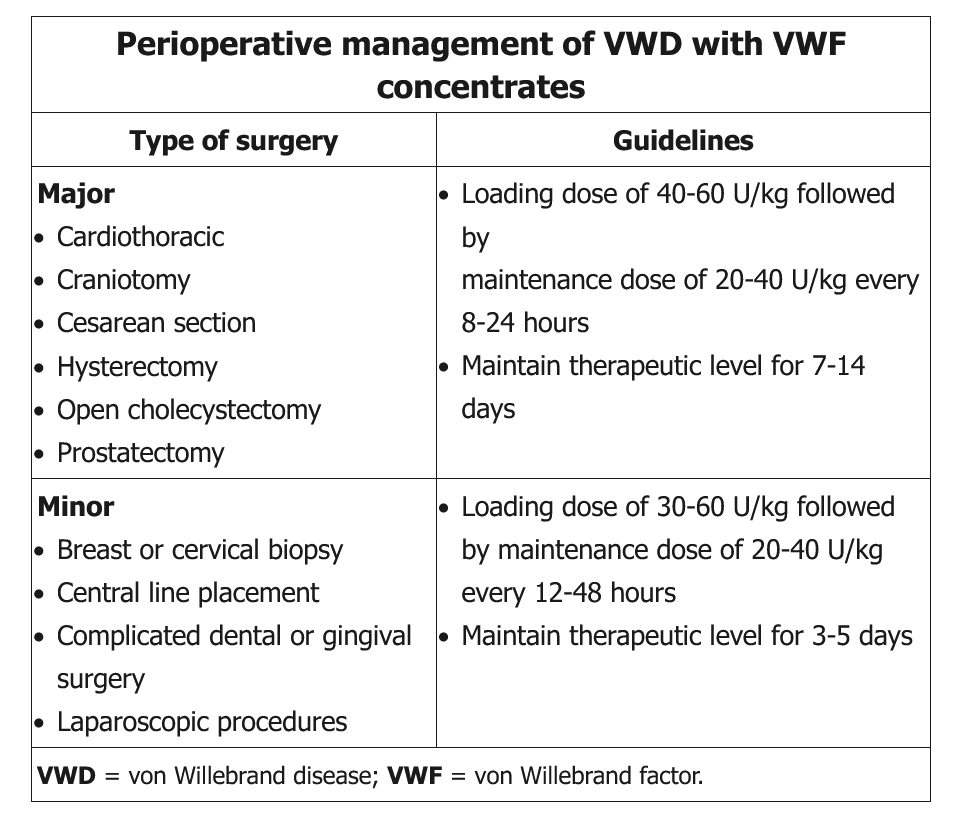

In all patients undergoing surgery, a careful preoperative bleeding history, including a family history, should be obtained to evaluate for underlying bleeding disorders and anemia. Laboratory testing should be reserved for patients with a suggestive history. Patients with known factor deficiencies, platelet function defects, and other coagulopathies should be managed by a hematologist.

In orthopedic and cardiac surgery patients and those with a history of stable CAD, the American Association of Blood Banks recommends a restrictive transfusion threshold (hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL [80 g/L]), as studies indicate that a restrictive threshold results in equivalent or improved patient outcomes. Similarly, in hospitalized hemodynamically stable patients, a transfusion threshold of 7 g/dL (70 g/L) is recommended.

The American Association of Blood Banks recommends a platelet transfusion threshold of 50,000/µL (50 × 109/L) for patients undergoing major non-neurologic surgery or lumbar puncture. Patients with mild thrombocytopenia due to immune thrombocytopenia are typically able to proceed to surgery at the recommended threshold. Postoperative thrombocytopenia warrants further evaluation, especially in patients with heparin exposure owing to the risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. See MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology for a discussion of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Perioperative Management of Endocrine Diseases

Diabetes Mellitus

Evidence demonstrates that patients with uncontrolled diabetes are at increased risk for perioperative complications, including surgical and nonsurgical infections, and postoperative mortality. Patients at high risk for diabetes, such as those with a history of impaired fasting glucose, should be evaluated for diabetes before elective surgery. In patients with established diabetes, it is reasonable to measure hemoglobin A1c within 3 months of surgery. There is not high-quality evidence on whether delaying surgery to improve glycemic control improves outcomes, although efforts should be made to optimize glycemic control before major elective surgery.

Oral and injectable noninsulin medications should be withheld 12 to 72 hours before surgery, replaced with supplemental insulin, and resumed at hospital discharge or when the patient has resumed a full diet. In patients taking insulin therapy, basal insulin should be continued perioperatively. The basal insulin dosage should not be reduced in patients with type 1 diabetes. Preoperative dosage reduction (often 25%-50%) may be considered in patients with type 2 diabetes who have a history of hypoglycemia with skipped or delayed meals.

Postoperatively, if the patient is eating, the ideal insulin regimen is a basal-bolus regimen, with prandial coverage and correction boluses for premeal hyperglycemia. For a discussion of the management of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting, see MKSAP 18 Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Thyroid Disease

Preoperative screening for thyroid disease is not recommended in the absence of symptoms. In patients with symptoms suggestive of thyroid disease or patients with hypothyroidism and a recent change in levothyroxine dosage, it is reasonable to obtain a preoperative thyroid-stimulating hormone level, although there are no guidelines to support such an approach.

In patients with hypothyroidism treated with levothyroxine, therapy should continue uninterrupted. Patients with untreated, asymptomatic mild hypothyroidism may proceed to surgery. A recent retrospective cohort study demonstrated that mild hypothyroidism (median thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 8.6 μU/mL [8.6 mU/L]) was not associated with an increase in perioperative mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, or infectious morbidity. In the presence of severe hypothyroidism, elective surgery should be postponed to prevent myxedema coma, arrhythmias, perioperative hypotension, and other complications.

Patients with well-controlled hyperthyroidism should be continued on therapy, including β-blockers and thionamides. Patients with uncontrolled hyperthyroidism are at risk for thyroid storm in the perioperative period, and surgery should be deferred until thyroid disease can be controlled.

Consultation with an endocrinologist is advised if emergent surgery is required in patients with severe thyroid disease.

Adrenal Insufficiency

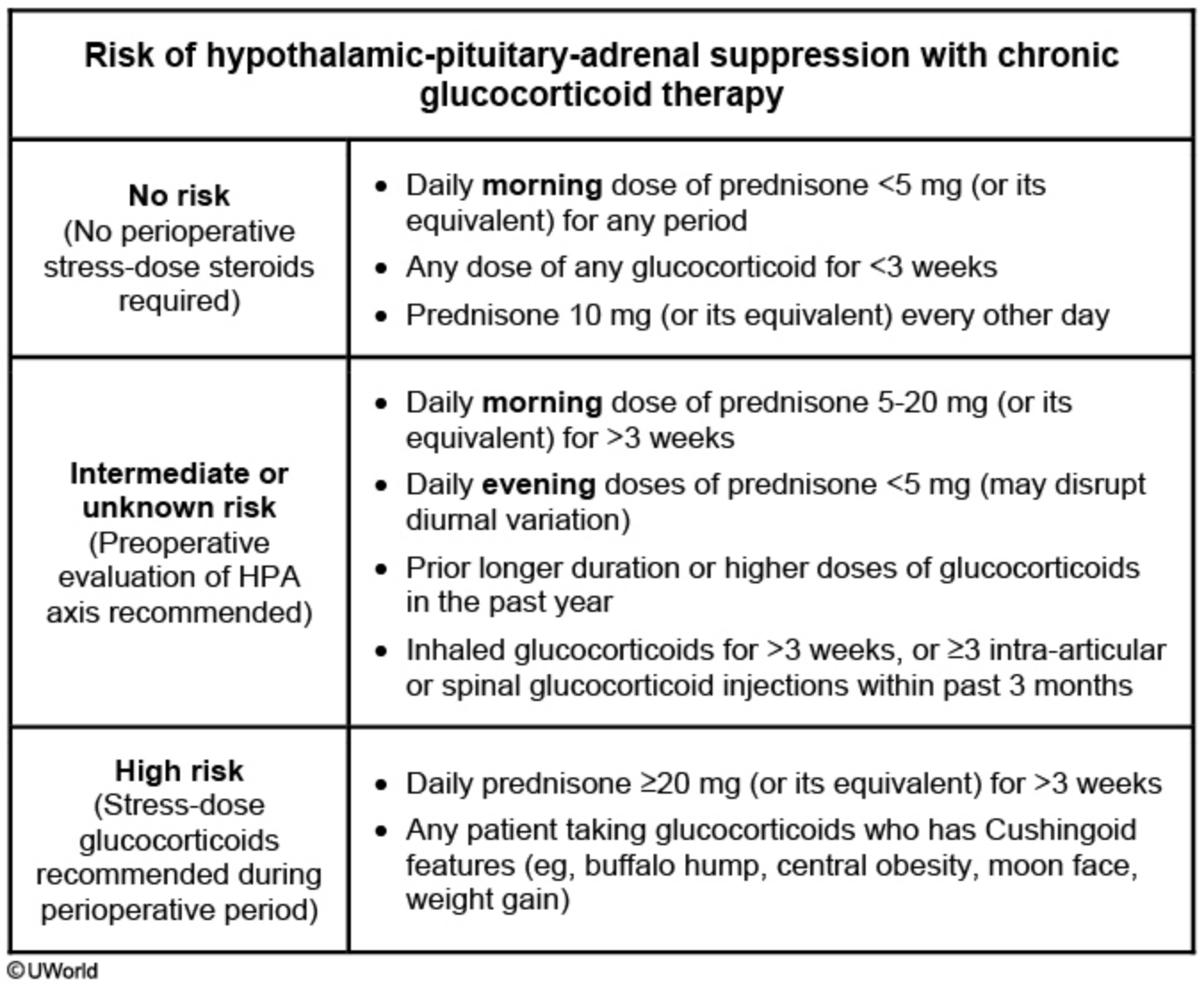

Patients with adrenal insufficiency should be evaluated for the need for perioperative supplemental glucocorticoid dosing, known as stress dosing. The decision to initiate perioperative stress dosing is guided by limited evidence, although one strategy uses patient characteristics and the degree of surgical stress to determine management (Table 101). Perioperative supplemental glucocorticoid dosing recommendations are provided in Table 102.

Perioperative Management of Kidney Disease

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at increased perioperative risk for fluid and electrolyte imbalance, metabolic acidosis, anemia, bleeding diathesis, and cardiac events, depending on the severity of the underlying disease. For patients undergoing hemodialysis, it is advisable to consult a nephrologist for review of the dialysate prescription, adjustment of fluid removal, and management of peridialysis heparin. Patients with less advanced CKD require correction of electrolyte abnormalities and optimization of volume status preoperatively. In all patients with kidney disease undergoing surgery, it is important to avoid iodinated contrast dye and other nephrotoxic agents and minimize perioperative hypotension.

Perioperative acute kidney injury portends an increased risk for postoperative CKD and, in those with underlying CKD, end-stage kidney disease. The two most important means of mitigating the risk for acute kidney injury are maintenance of renal blood flow and avoidance of further insults to the kidneys. Renal blood flow is maintained by avoiding renal hypoperfusion; effectively managing diuresis and antihypertensive medications; and treating anemia, which may impair peripheral vasodilation. Careful medication review is also warranted to ensure appropriate dosing based on renal clearance.

Perioperative Management of Liver Disease

Liver disease increases risk for perioperative infection, encephalopathy, bleeding, fluid retention, and acute kidney and liver decompensation. Patients with chronic liver disease require careful preoperative evaluation and risk stratification using the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification. Patients with compensated liver disease, including those with a MELD score of less than 8 to 10, are often able to proceed with surgery with optimal medical management. In patients with intermediate risk, referral to a hepatologist is reasonable before proceeding with surgery. Those with severe liver disease are at increased and often prohibitive risk for perioperative complications and death; patients with a MELD score greater than 15 should be referred for transplant evaluation before surgery if appropriate. Patients with Child-Pugh class C disease or a MELD score greater than 20 are at high risk for death, and all but the most urgent and life-saving surgeries should be avoided until after liver transplantation.

Complications of liver disease should be optimally managed in all patients; however, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends against perioperative transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement because of a lack of evidence that the procedure improves outcomes.

In general, patients with liver disease should be advised to abstain from alcohol consumption for at least 12 weeks before elective surgery.

Perioperative Management of Neurologic Disease

Patients with neurologic disease are at increased perioperative risk for loss of disease control, among other complications. In patients with epilepsy, perioperative seizure risk is thought to be driven by the severity of the underlying disease and seizure frequency, rather than by anesthesia or surgery type; an important exception is intracranial surgery, which may provoke seizures depending on the location of the surgery, underlying pathologic conditions, and required degree of brain manipulation. Antiepileptic medications should be continued uninterrupted. In patients who are unable to tolerate oral intake, alternate formulations should be used.

Patients with Parkinson disease are predisposed to perioperative delirium, hallucinations, orthostatic hypotension, and complications related to dysphagia. It is essential that patients maintain their normal treatment regimen. Surgery should be scheduled for as early in the day as possible to minimize missed doses, and antidopaminergic antiemetics should be avoided. Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome is a potentially life-threatening complication resulting from withdrawal of or reduction in the dosage of dopamine agonists; it is characterized by rigidity, fever, altered mental status, and autonomic instability.

Asymptomatic carotid bruit is a common finding in older adults but is not predictive of perioperative stroke and therefore requires no preoperative evaluation. Perioperative stroke is discussed in MKSAP 18 Neurology.

Delirium commonly occurs in the postoperative setting, especially in the elderly. Risk factors and treatment are similar to those for delirium in the general hospital setting (see MKSAP 18 Neurology).

Perioperative Management of the Pregnant Patient

In women of childbearing age, an accurate menstrual history should be obtained, and pregnancy testing should be performed if pregnancy is suspected. Many institutions require preoperative pregnancy testing in this population.

Elective surgery should be delayed until after pregnancy. Pregnant patients who require surgery should undergo the same preoperative medical evaluation as nonpregnant patients; additional diagnostic testing is unnecessary unless directed by the obstetrician. Modifications to surgical and anesthetic techniques may be required because of the anatomic and physiologic changes of pregnancy. Close collaboration among the obstetrician, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and internist is essential. Notably, pregnancy is considered a hypercoagulable state, and the ACCP recommends perioperative mechanical or pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis for pregnant patients. Although high-quality evidence is lacking, the current body of evidence suggests that surgery does not negatively affect obstetric or maternal outcomes.