Osteoarthritis

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic progressive multifactorial disorder of maladaptive cellular repair responses to joint stress. Previously deemed a “wear and tear” disease and an inevitable consequence of aging, OA is now recognized as a disorder driven by a complex interplay of genetics, joint injury, cell stress, extracellular matrix degradation, and inflammation. It affects all the tissues of the joint and is characterized by cartilage and meniscal degradation, subchondral bone changes (bone marrow lesions, subchondral sclerosis), and osteophyte formation. Other findings include synovial inflammation with hypertrophy and effusion as well as weakening of the periarticular muscle. Morphologic changes in cartilage reflect collagen and proteoglycan alterations driven by imbalanced anabolic and catabolic repair processes. In addition, inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor α are produced in the synovium and cartilage; they drive joint tissue destruction and stimulate synthesis of additional inflammatory mediators.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

OA is the most common form of arthritis worldwide and a leading cause of pain and disability, affecting approximately 30 million U.S. adults. OA is the leading cause of lower extremity disability among older adults, with an estimated lifetime risk for knee OA approaching 50%. Prevalence is projected to more than double by the year 2030, largely due to increasing obesity rates and aging of the population. Incidence and prevalence rates vary by joint and depend upon whether a clinical or radiographic definition is being applied. Recent efforts examining whether patients with OA are at increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality have been inconclusive, with positive associations appearing to relate more to functional decline and disability than to OA-specific pathologic processes.

Epidemiological risk factors for OA include age greater than 55, race/ethnicity, female sex, obesity, genetics, and occupations that include repetitive motions or physical labor. Age and female sex are strong nonmodifiable risk factors for OA of different sites. Obesity is the most important modifiable risk factor, especially for knee OA. Increased body mass is also a risk factor for hand OA, perhaps underscoring the systemic nature of the disease and a role for metabolic and/or inflammatory mechanisms in its pathogenesis. Single inherited conditions rarely predispose to OA; however, mutations in proteins involved in bone or articular cartilage structure or metabolism are possible risk factors.

Risk factors involving the joint itself include abnormal loading, injury, malalignment, and intrinsic cartilage or bone tissue defects. Injury may be acute (for example, anterior cruciate ligament tear) or may be more minor and repetitive (for example, physical labor or overuse); regardless of cause, injuries have been linked with the future development of OA of various sites. Hip dislocation, congenital dysplasia, femoroacetabular impingement, knee malalignment, and shape of the knee joint are also associated with incident OA.

Given its multifactorial etiology, an individual patient may develop OA as a consequence of one or more risk factors; how the interaction of these risk factors culminates in OA is complex and not fully understood.

Classification

Primary Osteoarthritis

The most common type of OA is primary OA, in which no identifiable proximal cause is recognized. Although almost any joint may be affected by OA, primary OA typically involves specific joints, including the distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) finger joints, the first carpometacarpal joint at the base of the thumb, the hip and knee joints, and the cervical and lumbar spine.

Erosive Osteoarthritis

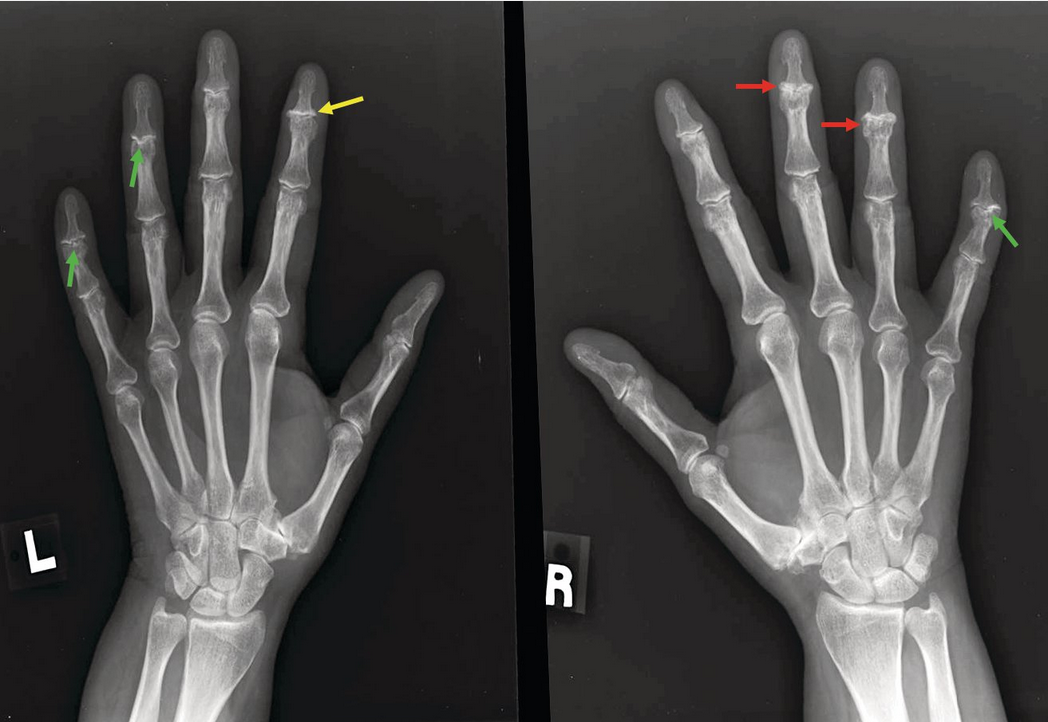

Erosive (inflammatory) OA is an aggressive subset of primary hand OA. Clinically, erosive OA mostly affects the DIP and PIP joints, is more inflammatory and painful than typical hand OA (with erythema and swelling), and is more common in women. Radiographs reveal diagnosis-defining central erosions (in contrast to marginal erosions seen in rheumatoid arthritis) with a “seagull” or “gull-wing” appearance in the finger joints (Figure 7); joint ankylosis (bony fusion) may also occur. Whether erosive OA comprises a separate disease entity or is part of the continuum of OA remains controversial.

Plain radiographs showing erosive hand osteoarthritis (OA). Note the classic “gull-wing” appearance of the fourth and fifth distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints on the left and the fifth DIP joint on the right (green arrows), reflecting central erosion of cartilage on the proximal surface of the joint. Also seen is bony ankylosis, a feature of erosive OA, of the right fourth DIP joint and developing in the right third DIP joint (red arrows). Additionally, the left second DIP joint exhibits the findings of classic (nonerosive) hand OA (joint-space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes without the “gull-wing” appearance) (yellow arrow).

Plain radiographs showing erosive hand osteoarthritis (OA). Note the classic “gull-wing” appearance of the fourth and fifth distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints on the left and the fifth DIP joint on the right (green arrows), reflecting central erosion of cartilage on the proximal surface of the joint. Also seen is bony ankylosis, a feature of erosive OA, of the right fourth DIP joint and developing in the right third DIP joint (red arrows). Additionally, the left second DIP joint exhibits the findings of classic (nonerosive) hand OA (joint-space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes without the “gull-wing” appearance) (yellow arrow).

Secondary Osteoarthritis

Secondary OA is historically defined in the presence of a predisposing disorder; however, an increasing number of risk factors are being identified for primary OA, thus blurring the lines between the primary and secondary forms of the disease. Pathologic changes, clinical presentations, symptoms, and management are indistinguishable between primary and secondary OA. When OA is observed in a joint not typically affected by primary OA, however, secondary causes should be entertained. Commonly recognized causes of secondary OA include a history of frank damage such as trauma, joint infection, or surgical repair (such as anterior cruciate ligament repair or meniscectomy); congenitally abnormal joints (for example, hip dysplasia); systemic metabolic, endocrine, and neuropathic disorders, particularly those that affect cartilage; and underlying inflammatory arthritis with accompanying damage (for example, rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis) (Table 15).

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

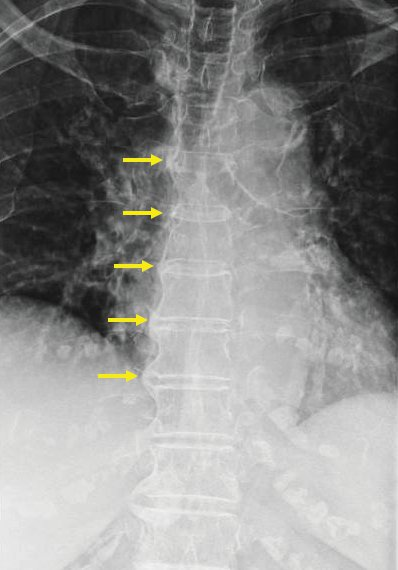

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a noninflammatory condition characterized by calcification and ossification of spinal ligaments (especially the anterior longitudinal ligament) and entheses (tendon and ligament attachments to bone). Unlike OA, DISH is more common in men. DISH usually presents as back pain and stiffness, with the thoracic spine most often involved. Although spinal ligamentous ossification is also seen in ankylosing spondylitis, the spinal calcifications in DISH are more “flowing,” wider and less vertically oriented than those seen with ankylosing spondylitis. There is additionally no involvement of the sacroiliac joints in DISH.

Radiographic changes characteristic of DISH include confluent ossification of at least four contiguous vertebral levels, usually on the right side of the spine (Figure 8). Patients with DISH have less involvement of the left side of the thoracic spine, perhaps secondary to the aorta serving as a mechanical barrier to the production of bony hyperostosis.

Plain lumbar radiograph of a patient with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Note the calcification at sites of tendinous and ligamentous insertion of the spine, taking the form of flowing ossification of multiple contiguous vertebrae (arrows). Also seen here is the typical extensive involvement of the right side of the spine and relative sparing of the left (calcification of the anterior longitudinal ligament is also common, but not readily observed in this view).

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

OA diagnosis is based on history and physical examination; radiography is confirmatory but may not be necessary. In early OA, clinical findings may not be accompanied by radiographic changes; conversely, some patients with prominent radiographic changes may have minimal or no symptoms. Patients with OA are typically over 50 years of age; diagnosis at an earlier age should prompt inquiry into a history of prior joint damage, endocrine or metabolic disorders, or a genetic proclivity for early disease.

Joints most commonly affected are the hands (DIPs and PIPs) (Figure 9), feet (first metatarsophalangeal joint and mid foot), knees, hips, and spine, but the distribution is variable. Localized OA, in which a single joint is affected, is more often a consequence of injury or joint asymmetry and often occurs in weight-bearing joints (hip or knee). Generalized OA, which affects multiple joint groups (for example, hands, spine, knees, and hips), is more likely the result of a combination of genetic and environmental factors and may be more symmetric in distribution.

Patients with OA usually describe an insidious onset of intermittent symptoms, which become more persistent and severe over time. The most common symptom is joint pain that is exacerbated by activity and alleviated with rest. Patients also describe morning stiffness usually lasting less than 30 minutes, in contrast to the prolonged morning stiffness of inflammatory arthritis. A single joint may initially be involved with eventual involvement of multiple joints.

On joint examination, crepitus, decreased range of motion, bony enlargement, and sometimes effusion may be present. Patients with long-standing hand OA may have Heberden and Bouchard nodes (bony enlargement of the DIP and PIP joints, respectively) and squaring of the first carpometacarpal joint. Hip involvement typically manifests as groin pain and decreased range of motion, especially internal rotation. Knee symptoms include pain on walking, especially on stairs, and difficulty transferring from a seated to standing position. Spondylosis, or OA affecting the spine, can affect the vertebral bodies, facet joints, and neural foramina, and may lead to spinal stenosis.

Patients with OA generally do not have systemic features. Pain and structural changes, however, ultimately result in functional impairment, pain, disability, psychosocial isolation, and reduced quality of life.

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

Laboratory testing is usually not necessary for diagnosis of OA but is helpful if other causes of arthritis are being considered, such as crystal arthropathy, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or hemochromatosis (all of which can coexist with OA). Acute phase reactants should be normal in OA. Routine laboratory testing (complete blood count, kidney and hepatic function) are not necessary for diagnosing OA but may be important when considering pharmacologic therapy, especially in the elderly and those with comorbidities.

If effusion is present, evaluation for concurrent crystal arthritis, infections, or other inflammatory causes should be considered, ideally by synovial fluid analysis. OA synovial fluid is typically clear in appearance and noninflammatory, with a leukocyte count ≤2000/µL (2.0 × 109/L).

Although imaging is not necessary to make an OA diagnosis, it can be helpful to confirm the diagnosis, establish baseline severity, and exclude other diagnoses. Radiographic features of OA include asymmetric joint-space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, osteophytes, and bone cysts; however, these changes may not be present in early disease. Even in established OA, symptoms may correlate poorly with imaging findings. Although MRI and ultrasonography can detect subtle OA changes at an earlier stage and are increasingly used in OA research, they are not needed for routine OA diagnosis. MRI may be indicated in the setting of symptoms suggestive of a concomitant mechanical disorder (joint catching, locking, instability), but incidental abnormalities such as meniscal tears are commonly seen on MRI in patients with OA and may prompt unnecessary surgical intervention.

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosing OA may be problematic when OA is present in atypical joints, when an accurate history is difficult to obtain, or when a concurrent inflammatory arthropathy may be present. Calcium pyrophosphate deposition may occur in joints also typical for OA (hands or knees) but is associated with intermittent “flares,” and radiographs show cartilage calcification (chondrocalcinosis). Gout and OA commonly co-associate, particularly in the DIP joints. Rheumatoid arthritis typically affects the hands, but unlike OA, the DIP joints are rarely affected, and signs and symptoms of chronic and persistent inflammation are seen. The presence of rheumatoid factor, anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, and elevated inflammatory markers favors the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis but does not eliminate the possibility of concurrent OA. Psoriatic arthritis can involve the DIP joints, but also commonly includes prolonged morning stiffness, joint swelling, dactylitis, and a history of psoriasis. Synovial fluid analysis can also be helpful in distinguishing between OA and these inflammatory disorders.

Other conditions to consider when evaluating a patient for OA include nonarticular sources of pain such as bursitis and tendinitis. Hip pain that is not in the anterior groin but instead around the lateral hip and buttock may indicate trochanteric bursitis or lumbosacral radiculopathy. Similarly, knee pain may be secondary to pes anserine bursitis or iliotibial band syndrome rather than intra-articular pathology. The pes anserine bursa is located along the proximal medial aspect of the tibia; thus, pes anserine bursitis should be considered when there is spontaneous pain along the inner (inferomedial) aspect of the knee joint. Patients with iliotibial band syndrome typically present with pain at the lateral aspect of the knee, usually exacerbated by physical activity, such as walking up or down stairs, running, or cycling.

Management

To date, no agents have been FDA approved to prevent, delay, or remit the structural progression of disease in OA. Instead, current treatment is directed to the management of pain and disability. Evidence-based guidelines for OA management are available from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI), the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), and others; however, there is poor consensus among these guidelines. Nevertheless, there is agreement that optimal OA management requires a combination of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Patients with OA should receive individualized multidisciplinary treatment that takes into account their expectations, functional and activity levels, occupational and vocational needs, joints affected, severity of disease, and any coexisting medical problems.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

The nonpharmacologic approach to OA starts with assessment of physical status, activities of daily living, health education, motivation, beliefs, and other biopsychosocial factors. An individualized management plan includes education on OA and joint protection, an exercise regimen, weight loss, proper footwear, and assistive devices as appropriate. Physical activity includes graduated aerobic exercise and strength training, with attention paid to strengthening periarticular structures and minimizing injury. Tai chi has also been shown to be as beneficial as physical therapy for knee OA pain and is strongly recommended by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) for knee and hip OA. A recent study reports that the combination of diet and exercise is more effective at decreasing OA-related knee pain and dysfunction than either diet or exercise alone. Furthermore, a 2015 Cochrane review, which included 54 knee OA studies, concluded that land-based therapeutic exercise provides short-term benefit in terms of reduced knee pain and improved physical function that is sustained for at least 2 to 6 months after cessation of formal treatment. The ACR also conditionally recommends cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and thermal interventions (locally applied heat or cold) for knee, hip, and hand OA. Balance exercises are conditionally recommended by the ACR for knee and hip OA, and yoga is recommended for knee OA.

Pharmacologic Therapy

In the absence of disease-modifying OA drugs, pharmacologic treatment is considered when symptoms are present and bothersome to the patient. Pharmacologic therapy for OA includes oral, topical, and intra-articular medications. Choice of treatment(s) depends upon individualized assessment, with particular attention to comorbidities, concomitant medications, and especially adverse effects of the treatments. See Principles of Therapeutics for details on the medications used in OA.

Oral and Topical Agents

Oral agents include acetaminophen, NSAIDs, duloxetine, and tramadol. The ACR conditionally recommends acetaminophen for knee, hip, and hand OA for patients with limited pharmacologic options. Oral NSAIDs are the mainstay of treatment in OA and are strongly recommended. However, their side-effect profiles make sustained use problematic, especially in the elderly and those with comorbidities. If used, the proper choice of an NSAID, considering drug pharmacokinetics as well as gastrointestinal and cardiovascular effects, may improve tolerance and minimize risk. Duloxetine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with central nervous system activity, has shown efficacy for knee OA pain, implicating the role of central sensitization in OA pain modulation. A 2018 randomized controlled trial demonstrated that opioids were not superior to nonopioid medications for improving pain-related function for chronic back pain or OA-related hip or knee pain; pain intensity was significantly improved in the nonopioid group. The 2019 ACR guidelines conditionally recommend against nontramadol opioids in patients with knee, hip, or hand OA; use can be considered in limited circumstances when no other alternatives exist. Tramadol and duloxetine are conditionally recommended for knee, hip, and hand OA; concerns about the potential adverse the adverse effects of tramadol continue.

Topical NSAIDs are strongly recommended for patients with knee OA and conditionally recommended for patients with hand OA. However, topical NSAIDs are associated with more skin reactions and are more expensive than oral NSAIDs. Topical capsaicin is conditionally recommended for knee OA but not for hand OA.

The oral alternative therapies glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are frequently used by patients; although they appear to be safe, the quality of evidence for their efficacy is poor. The ACR strongly recommends against the use of glucosamine in patients with knee, hip, and/or hand OA. Chondroitin sulfate is strongly recommended against in patients with knee and/or hip OA, as are combination products that include glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate; however, chondroitin is conditionally recommended for patients with hand OA.

Intra-Articular Injections

Related Question

- Question 89

Patients with knee or hip OA who have inefficacy, intolerance, or contraindication to oral and topical therapies may benefit from intra-articular glucocorticoid injections. The ACR strongly recommends using ultrasound guidance for hip-joint glucocorticoid injections.

Intra-articular glucocorticoids are efficacious in knee and hip OA and are supported by multiple treatment guidelines; the ACR conditionally recommends intra-articular glucocorticoids for hand OA. Long-term harm has not been demonstrated; however, benefit is usually short term and usually wanes within 3 months. Injections can be administered repeatedly but are not usually given more often than every 3 months. A recent 2-year study has called the efficacy and long-term safety of intra-articular glucocorticoid injections into question, with possible negative effects on cartilage thickness, an outcome with unclear clinical meaning.

The ACR strongly recommends against intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections in hip OA and conditionally recommends against such injections in knee and/or first carpometacarpal joint OA.

Surgical Therapy

Surgery for OA is considered when nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches fail to control pain or functional limitation. Multiple high-quality studies have shown that arthroscopic surgery for knee OA provides no better outcomes than conservative management unless there is joint buckling, instability, or locking or a concomitant and symptomatic mechanical disorder.

In contrast, total joint replacement is a “curative” option for those who have failed conservative therapies, providing pain relief and functional improvement. Overall, long-term outcomes are excellent, although hardware loosening and late infection may occur.

Recent studies suggest that for morbidly obese patients with knee OA, bariatric surgery may result in significant improvement in pain and function even without further OA management.