Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

- related: ID

- tags: #id

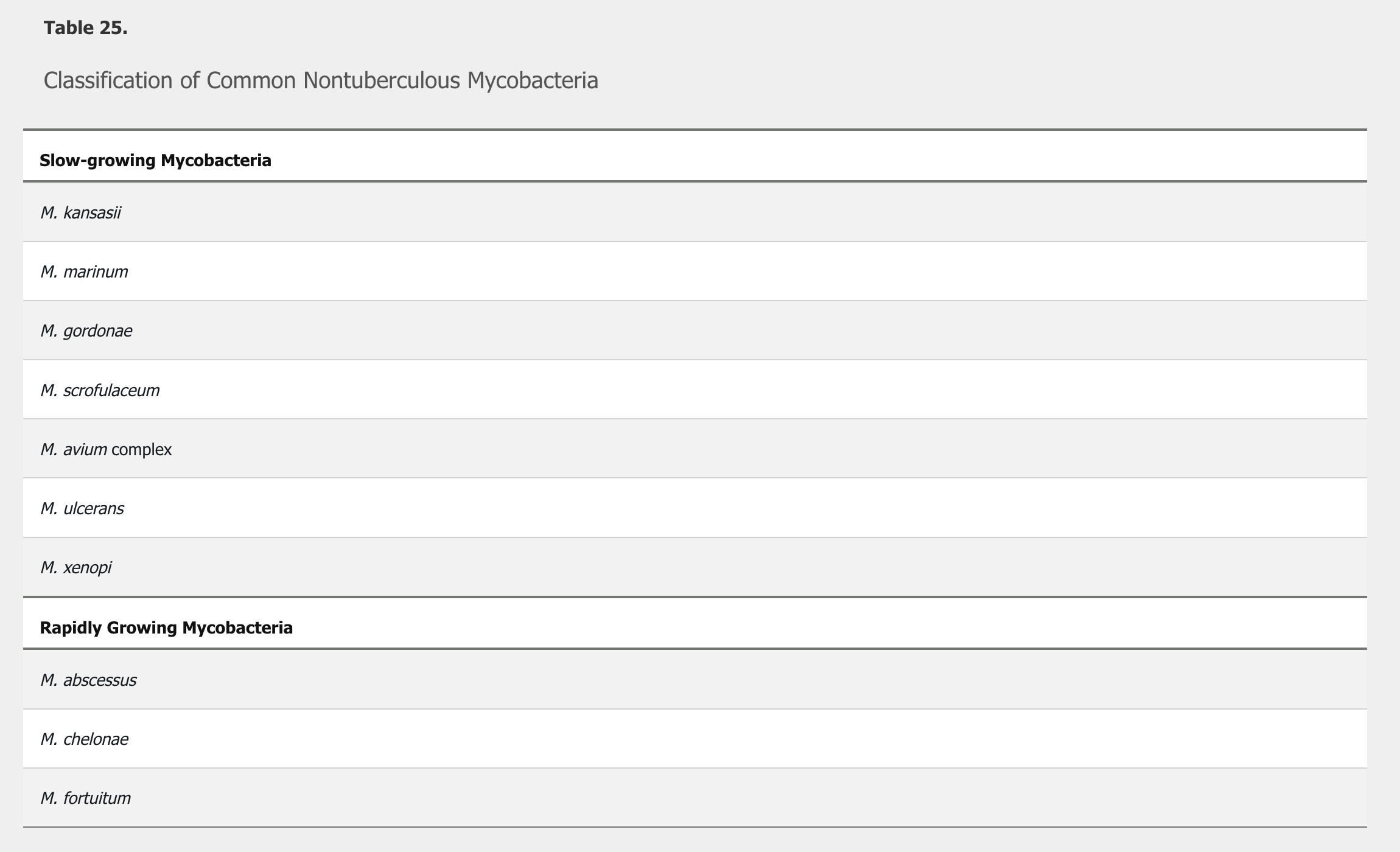

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) comprise species other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and Mycobacterium leprae. NTM are often divided into slow and rapid growers (Table 25). These organisms are found in surface water, soil, domestic and wild animals, milk, and food products. Additionally, they can be colonizers, particularly in the airways of persons with chronic lung disease. They can cause a spectrum of infections (Table 26).

Risk factors for NTM infections include immunocompromise, chronic lung disease, and postoperative status. Health care–associated Mycobacterium chimaera infections have been documented worldwide in association with heater-cooler units used during cardiac surgery.

NTM diagnosis is difficult because a positive culture result from a nonsterile site (such as the lung) without other evidence of disease may reflect colonization rather than infection. However, when recovered from a normally sterile site, active infection is very likely. Because antibiotic susceptibility of species vary, it is important to identify organisms to species level. American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines (updated in 2020) recommend fulfillment of clinical, radiologic, and microbiologic criteria to diagnose an NTM pulmonary infection. Treatment is recommended for patients meeting diagnostic criteria, especially if acid-fast sputum smears are positive and/or cavitary lung disease is present. Most NTM infections require treatment with two to four antimicrobials; ATS guidelines should be used to guide therapy.

Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection

Mycobacterium avium complex is the most common cause of chronic lung infection worldwide. Cavitary lung disease is seen classically in white, middle-aged, or older adult men, especially those with underlying lung disease, such as COPD, cystic fibrosis, or interstitial lung disease. Disseminated infection is seen predominantly in patients with HIV with CD4 cell counts less than 50/µL. The clinical presentation often consists of fever, night sweats, weight loss, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Mycobacterium kansasii

M. kansasii infection mimics pulmonary tuberculosis with cavitary lung disease. Predisposing conditions include underlying lung disease, alcoholism, cancer, and immunocompromised status.

Rapidly Growing Mycobacteria

Rapidly growing NTM have been implicated in NTM outbreaks. The most common rapidly growing mycobacterial species include M. abscessus, M. chelonae, and M. fortuitum. Of these, M. abscessus is most frequently identified and one of the most difficult to treat. These mycobacteria are associated with chronic, nonhealing ulcers unresponsive to appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy for typical skin and soft tissue infections.

Although M. fortuitum is not part of the differential diagnosis of acute wound infections, NTM should always be considered in chronic wounds, especially when conventional antimicrobial therapy has been ineffective. To diagnose an NTM infection, a deep biopsy of chronic wound tissue should be performed. The biopsy specimen should be sent for histopathology to stain for bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi, and a portion should be sent to the microbiology laboratory for similar stains and cultures.

Mycobacterium marinum

M. marinum is found worldwide in freshwater and saltwater aquatic environments, including swimming pools. Skin infections have typically been reported after skin trauma and contact with fish tanks (“fish tank granuloma”), fish, or shellfish. Hobbies and occupations predisposing to infection include aquatic sports enthusiasts, fishermen, seafood workers, and owners of fish tanks. The incubation period is usually less than 1 month, and the clinical course is often insidious. Infection usually manifests initially as a violaceous or erythematous papule or nodule that may ulcerate at the site of inoculation. Lesions may be solitary or multiple; occasionally, a sporotrichoid distribution along the lymphatic vessels may develop. The upper extremities, including the hands, fingers, or elbows, are commonly involved. Diagnosis is often delayed and is established by isolation of the organism from culture of a biopsy, aspirate, or drainage specimen. Granulomas may be present and provide evidence of potential mycobacterial infection.