Neuro Oncology

- related: Neurology

- tags: #neurology

Approach to Intracranial Tumors

Both benign and malignant intracranial tumors can have devastating neurologic consequences because of the obvious space constraints within the skull and potential surgical inaccessibility (if in the thalamus or brainstem, for example). Presenting symptoms of intracranial tumors appear in Table 51. Intracranial tumors most often present with a slow, progressive course of neurologic symptoms. Acute symptoms typically occur when a tumor causes seizure or hemorrhage.

Headache is a common symptom, although the classic early morning headache is uncommon. Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) can cause the headache to increase with coughing, sneezing, straining, or the Valsalva maneuver. Elevated ICP also is associated with nausea, vomiting, blurry vision, papilledema, and an inability to abduct the eyes (bilateral abducens nerve [cranial nerve VI] palsy). Elevated ICP also can lead to life-threatening herniation, syncope, or cerebellar “fits” (episodic extension, flexion and stiffening of limbs; loss of consciousness; slowed or irregular respiration; and pupil dilation), which may be confused with seizures.

Head CT without contrast may be useful emergently to assess for hemorrhage or herniation but is not very sensitive for detecting the presence of a mass lesion, especially in the posterior fossa. Brain MRI is the preferred diagnostic modality; contrast administration improves diagnostic sensitivity. Management is determined by tumor location and pathology.

Key Point

- Head CT without contrast may be useful emergently to assess for hemorrhage or herniation, but brain MRI is the preferred diagnostic modality for the evaluation of intracranial tumors.

Metastatic Brain Tumors

Brain metastases are the most common intracranial tumors. The most likely sources are lung, breast, and kidney cancers and melanoma. Metastases can be solitary but are more often multiple. These metastases typically appear as ring-enhancing lesions on postcontrast MRIs, usually at the gray-white cortical junction. Survival is generally measured in weeks to months. Most brain metastases are treated with whole-brain or more targeted radiation (stereotactic radiosurgery). Resection may increase survival in younger patients with good baseline function and a single or limited number of metastases; it may also be considered when the underlying diagnosis is uncertain.

Carcinomatous meningitis is a rare diagnosis that requires a high index of suspicion to identify; presenting symptoms are variable and include headache, neurologic deficits, and altered mental status. MRI typically shows nodular meningeal enhancement. Patients with leukemia or lymphoma whose initial symptoms are cranial nerve deficits or radiculopathy may have evidence of nerve root enhancement on postcontrast MRI of the brain and/or spine. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis with cytology and often flow cytometry is required to make the diagnosis; because of limited sensitivity of CSF cytology, repeat lumbar puncture is sometimes needed to establish the diagnosis.

Key Points

- Brain metastases are the most common intracranial tumors that typically appear as ring-enhancing lesions on postcontrast MRIs at the gray-white cortical junction.

- Most brain metastases are treated with whole-brain or more targeted radiation (stereotactic radiosurgery), but resection of a single or limited number of intracranial metastases may increase survival in younger patients with good baseline function.

Primary Central Nervous System Tumors

Meningiomas

Meningioma is the most common primary type of central nervous system (CNS) tumor. Often found incidentally, meningiomas are benign dural-based tumors that typically show homogenous enhancement on postcontrast MRI. They have a smooth, rounded shape and often a “tail” that tracks along the dura outside the brain parenchyma (Figure 30). On noncontrast images, meningiomas may be hypointense or isointense and thus not readily seen. Because of their characteristic MRI appearance, many meningiomas are followed clinically, without resection or biopsy, unless they are accompanied by significant clinical deficits, drug-resistant seizures, severe headaches, or peritumoral edema.

Key Point

- Meningioma is the most common primary type of central nervous system tumor and has a characteristic MRI appearance; the tumor is resected only if accompanied by significant clinical deficits, drug-resistant seizures, severe headaches, or peritumoral edema.

Glioblastoma Multiforme

Glioblastoma multiforme (Figure 31) is the most common and most aggressive glioma subtype in adults. Previous exposure to medical therapeutic radiation is the only consistent risk factor for developing gliomas. There is no evidence that environmental electromagnetic fields, cell phones, or smoking increase tumor risk. Gliomas rarely metastasize, and routine evaluation of patients with glioblastoma multiforme with lumbar puncture or MRI of the spinal cord is not recommended unless dictated by focal findings.

An MRI typically shows a large, space-occupying lesion with central necrosis, mass effect, and surrounding edema. Lower-grade gliomas may not enhance. Treatment is usually resection, if possible, followed by radiation and chemotherapy. Temozolomide, nitrosoureas, and bevacizumab can be used. Prognosis is dependent on pathologic type; 5-year survival rates for glioblastoma multiforme are less than 10%, and survival is often measured in months. Prognosis is better in patients who are younger than 45 years, have an excellent functional status, have minimal residual tumor after resection, and receive chemotherapy and radiation after surgery.

Key Points

- Previous exposure to medical therapeutic radiation is the only consistent risk factor for developing gliomas, including glioblastoma multiforme.

- Prognosis in glioblastoma multiforme is better in patients who are younger than 45 years, have an excellent functional status, have minimal residual tumor after resection, and receive chemotherapy and radiation after surgery.

Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

Related Question

- Question 45

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) initially occurs without systemic or lymph node involvement. Its typical pathologic appearance is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Immunodeficiency is the most consistent risk factor, but PCNSL incidence is increasing in older, immunocompetent patients. On MRI, PCNSL appears as a single, well-demarcated, deep white matter (periventricular) lesion with minimal mass effect or edema. The radiologic appearance of PCNSL can be confused with inflammatory or demyelinating lesions.

PCNSL evaluation should include HIV testing, lumbar puncture (if not contraindicated because of elevated ICP), and ophthalmologic evaluation with vitreous fluid sampling. Lymphomatous cells in vitreous or CSF samples (from cytology and flow cytometry) can add to diagnostic sensitivity and may obviate the need for biopsy. Systemic staging should include bone marrow biopsy, testicular ultrasonography, and whole-body PET or CT. Empiric glucocorticoids should be avoided before biopsy because they can temporarily suppress lymphoma and prevent or delay a tissue diagnosis.

Surgery and typical chemotherapeutic regimens for systemic lymphoma are usually ineffective in PCNSL. High-dose intravenous (IV) methotrexate combined with rituximab is the mainstay of treatment and at times is followed by subsequent radiation. Intrathecal chemotherapy has not been prospectively studied. Despite being chemo- and radiosensitive, PCNSL typically has multiple recurrences and a generally poor prognosis.

Key Points

- Immunodeficiency is the most consistent risk factor for primary central nervous system lymphoma, but its incidence is increasing in older, immunocompetent patients.

- Empiric glucocorticoids should be avoided before biopsy because they can temporarily suppress lymphoma and prevent or delay a tissue diagnosis.

Medical Management of Complications of Central Nervous System Tumors

Seizures

Seizures are more common in low-grade than high-grade tumors. Tumors near the cortex, especially the temporal lobe or primary motor cortex, are especially associated with seizures. White matter and posterior fossa tumors, on the other hand, typically do not cause seizures. Gangliogliomas and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors provoke medication-resistant seizures in more than 90% of patients, and these tumors should be resected, if possible. Seizures may not be directly caused by the CNS tumor but rather by associated conditions or treatment, such as electrolyte disturbances, infection, chemotherapy, or paraneoplastic encephalitis.

In patients with CNS tumors not associated with seizures, prophylactic antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are not recommended, although they may be used for 1 week immediately postresection. In patients with seizures, older AEDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, valproic acid, carbamazepine) should be avoided because of drug interactions and adverse effects. Levetiracetam and lacosamide are the preferred AEDs because of their lack of drug interactions, IV availability, better tolerability, and rapid titration to a therapeutic dose. Unprovoked seizures occurring after resection typically require lifelong AED treatment.

Key Points

- Gangliogliomas and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors provoke medication-resistant seizures in more than 90% of patients; therefore, patients with these tumors should be referred for resection, if possible.

- In patients with central nervous system tumors not associated with seizures, prophylactic antiepileptic drugs are not recommended, although they may be used for 1 week immediately postresection.

Edema and Herniation

Related Question

- Question 69

Brain edema can lead to focal neurologic deficits, elevated ICP, or herniation. Brain herniation inevitably leads to death if unrecognized. It manifests as an abrupt decline in mental status, unreactive dilated pupils, and motor weakness with flexor or extensor posturing. Emergent treatment includes elevation of the head of the bed to 30 degrees, hyperventilation (usually with mechanical ventilation) to an arterial PCO2 of 20 to 25 mm Hg (2.7-3.3 kPa), infusion of either hypertonic saline or mannitol, and administration of glucocorticoids. These treatments can be life-saving and often are used as a bridge to emergent surgery. Among the glucocorticoids, dexamethasone is preferred because of its lack of mineralocorticoid effects. Antiangiogenic agents, such as bevacizumab, can be used as glucocorticoid-sparing agents but take weeks or months to have an effect. Both glucocorticoids and antiangiogenic agents may seal the blood-brain barrier and thus “hide” the previously contrast-enhancing residual tumor.

Key Points

- In patients with central nervous system tumors, brain herniation inevitably leads to death if unrecognized.

- Emergent treatment of brain herniation includes elevation of the head of the bed, hyperventilation, infusion of either hypertonic saline or mannitol, and administration of glucocorticoids.

Venous Thromboembolism

Related Question

- Question 26

Certain characteristics are associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with CNS tumors (Table 52). Despite the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, therapeutic anticoagulation is generally recommended in confirmed thromboembolic disease. Anticoagulation has historically been avoided in melanoma, choriocarcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, and renal carcinoma because of an assumed increased risk of hemorrhage. However, recent studies have not shown that anticoagulation increases hemorrhage risk in patients with these cancers. Besides the usual contraindications, anticoagulation should be avoided in patients with previous intracranial hemorrhage and a platelet count less than 50,000/μL (50 × 109/L). The presence of a CNS tumor is a contraindication for thrombolytic therapy in pulmonary embolism, although exceptions may be made for low-risk tumors, such as meningiomas. Although evidence does not support routine use of preanticoagulation neuroimaging to assess for hemorrhage, noncontrast head CT is the most cost-effective test in this situation.

Low-molecular-weight heparin is generally preferred over unfractionated heparin. Exceptions include kidney impairment and a higher hemorrhage risk when rapid reversal may be required. Inferior vena cava filters have considerably high rates of complications and should be reserved for patients with an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation. Warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin may be considered for long-term therapy, although medication interactions between warfarin and chemotherapy or AEDs are a concern. Evidence is insufficient to recommend the non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for patients with CNS tumors.

Prophylactic anticoagulation in combination with mechanical devices is recommended in hospitalized patients with CNS tumors as soon as possible after resection. Chronic outpatient prophylactic anticoagulation is not recommended.

Key Points

- Despite the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, therapeutic anticoagulation is generally recommended in confirmed venous thromboembolic disease.

- Prophylactic anticoagulation in combination with mechanical devices is recommended in hospitalized patients with central nervous system tumors as soon as possible after resection.

Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes

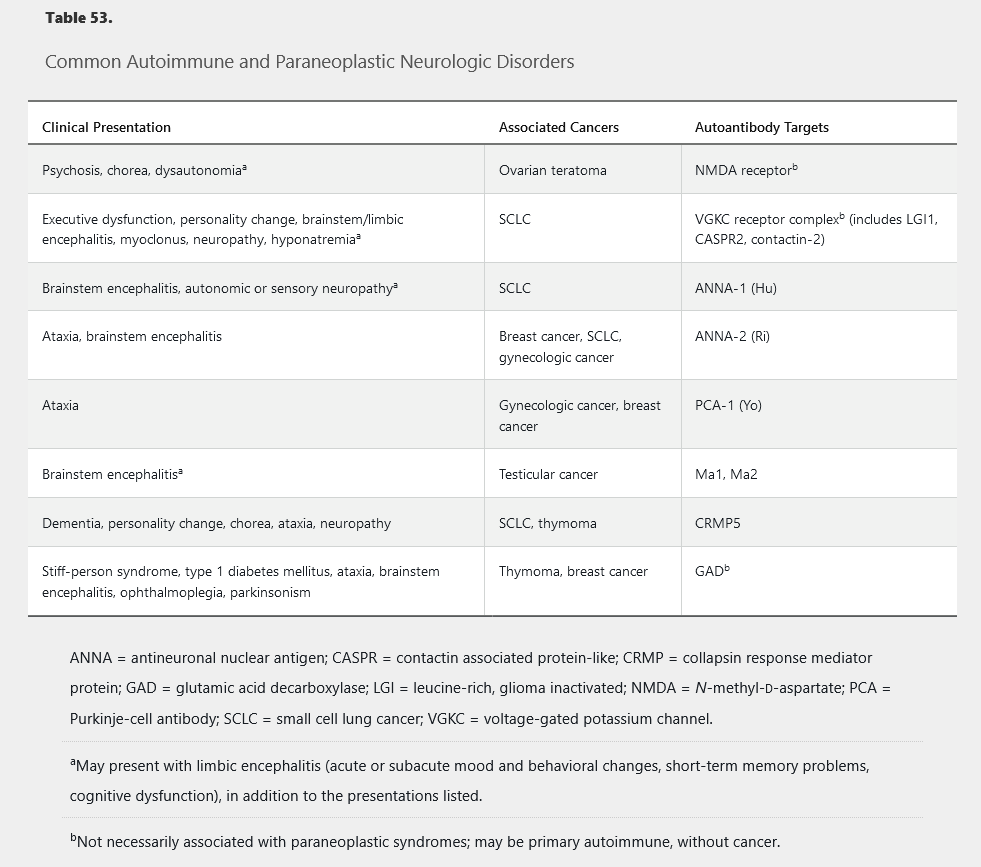

Antibody-mediated neurologic syndromes may occur as primary autoimmune or paraneoplastic disorders. Various syndromes have been described with different neurologic manifestations and findings on serum and CSF studies (Table 53). Suggestive symptoms include new-onset status epilepticus in a patient without epilepsy, acute psychosis in a healthy patient, acute movement disorder (ataxia, chorea, myoclonus, tremor), acute progressive peripheral neuropathy, and systemic signs of malignancy (severe anorexia, weight loss, lymphadenopathy).

Evaluation should include brain MRI with contrast, antibody testing of the blood and CSF, and imaging (full-body CT, body and brain PET, and ultrasonography, as appropriate) for tumor detection. Treating the symptoms directly is ineffective without appropriate tumor resection and immunotherapy. Even when the tumor is removed, immunotherapy may be needed. Acute management with IV immune globulin or IV methylprednisolone is often helpful. Chronic treatment with azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, or rituximab may be considered.