Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Epidemiology

Tuberculosis is one of the oldest and most prevalent infectious diseases in the world. It remains one of the most common causes of death from an infectious disease worldwide. Although rates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection remain relatively low in North America, approximately one third of the world's population is infected with the bacteria. As of 2015, approximately 10 million new cases are reported each year throughout the world, and approximately 2 million deaths are documented each year, including 360,000 in persons infected with HIV. More than 60% of infections are reported from Southeast Asia, India, China, Micronesia, Russia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) accounts for 3.3% of new infections and 20% of relapsed infections. Extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis now accounts for approximately 10% of all MDR-TB infections worldwide. In 2015, 9557 tuberculosis infections were reported in the United States (3.0 per 100,000 persons). Most infections in the United States occur in foreign-born persons; however, other persons at high risk include those with alcoholism, urban poor, homeless persons, injection drug users, prison inmates, persons living in shelters, HIV-positive persons, and older adults.

Despite great strides worldwide in controlling M. tuberculosis, it remains a major global health concern. The burden of disease throughout the world and rapid travel from country to country ensures a steady stream of active tuberculosis cases in the United States.

Pathophysiology

Humans are the only known reservoir for M. tuberculosis, which is most commonly transmitted from person to person by aerosolized droplets. Although the droplets dry rapidly, the smallest droplets may remain suspended in the air for several hours. Persons who have visible acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on microscopy are the most likely to transmit infection. The most contagious patients are those with cavitary or laryngeal tuberculosis and those whose sputum contains a high bacterial load. After deposition in the respiratory tract, tubercular bacilli are ingested by alveolar macrophages that initiate an immunologic cascade eventually resulting in the development of classic caseating granulomas.

Most persons (>90%) who become infected with M. tuberculosis remain asymptomatic and develop latent tuberculosis. The risk of developing disease after infection depends primarily on endogenous factors such as the person's innate immune system, nonimmunologic defenses (alveolar macrophages, phagosome formation, phagocytosis), and the function of cell-mediated immunity. Specific risk factors for developing active tuberculosis among infected persons are shown in Table 20. The risk for developing active infection is approximately 5% in the first 2 years after infection and then 5% for the remainder of their life, assuming no cause of immunosuppression is present (see Table 20).

Clinical Manifestations

Tuberculosis is classified as pulmonary, extrapulmonary, or both; the two main forms are primary and secondary tuberculosis. Primary tuberculosis occurs soon after the initial infection, most frequently in children and immunosuppressed persons. Often, the lesions heal spontaneously. Secondary or reactivation tuberculosis results from endogenous reactivation of a latent infection. Most cases of active tuberculosis are caused by reactivation of latent tuberculosis in the setting of immunosuppression. Seventy-five percent of secondary infections are pulmonary, except in those infected with HIV, in whom two thirds of patients have pulmonary and extrapulmonary infection.

Frequent manifestations include fever, weight loss, productive cough (occasionally blood tinged), anorexia, malaise, and pleuritic chest pain. Patients may have a normal lung examination or have crackles, rhonchi, or dullness to percussion. Hemoptysis occurs in 10% to 20% of patients with positive AFB smear results. In immunosuppressed patients, the infection may also disseminate into the bloodstream, producing miliary (disseminated) tuberculosis, which can result in a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, septic shock, and ultimately death if not diagnosed and treated early. Additionally, patients with disseminated infection may present with atypical clinical manifestations and chest radiographs. Extrapulmonary disease may be the result of hematogenous dissemination, can be seen in up to 30% of patients with active tuberculosis, and may involve almost any organ or organ system, including the pleura, lymph nodes, central nervous system, skeletal system, pericardium, larynx, peritoneum, and genitourinary system.

Diagnosis

The key to the diagnosis of tuberculosis is a high index of suspicion in patients at high risk.

Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis Infection

The goal of diagnosing latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) is to identify and treat persons at increased risk for reactivation tuberculosis. Testing methods include interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) performed on a blood sample or tuberculin skin testing (TST). LTBI is diagnosed when an asymptomatic patient has a positive TST result or an IGRA with no clinical or radiographic manifestations of active tuberculosis.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends performing an IGRA rather than a TST in persons 5 years or older who are likely to have M. tuberculosis infection, have a low or intermediate risk of disease progression, have a history of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination, or are unlikely to return to have their TST result interpreted. IGRAs are in vitro assays that measure T-cell release of interferon-γ in response to stimulation with highly tuberculosis-specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 (QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube and T-SPOT TB test). IGRAs are more specific than TST because they have less cross-reactivity resulting from BCG vaccination and sensitization by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Although not used to diagnose active tuberculosis, IGRAs appear to be at least as sensitive as the TST in patients with active tuberculosis.

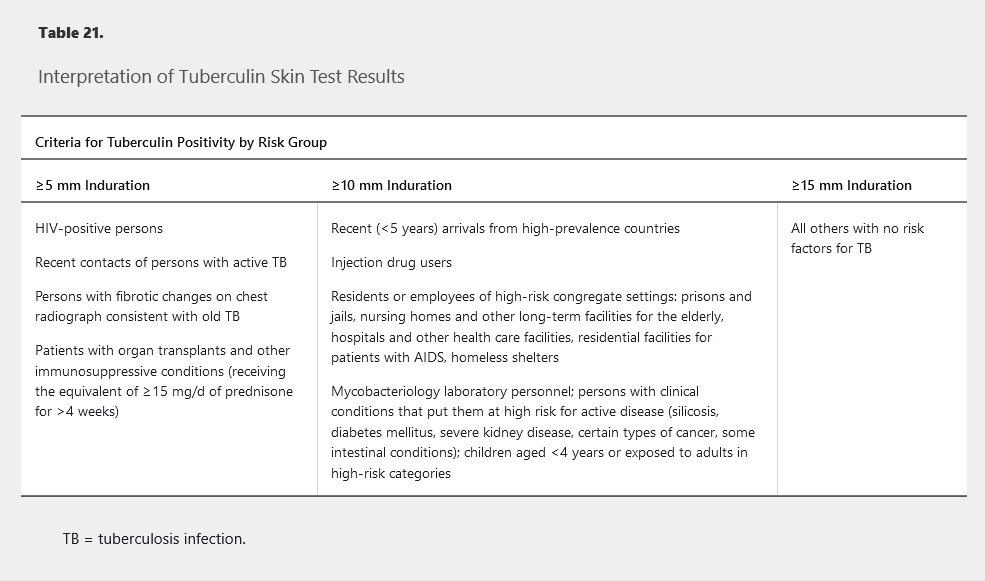

TST has become the alternative diagnostic test if IGRA is not feasible or available. The purified protein derivative is injected intradermally and interpreted after 48 to 72 hours by measuring the transverse diameter of induration, not erythema. A positive result indicates delayed-type hypersensitivity response. The criteria for a positive TST result are based on the patient's risk factors for tuberculosis (Table 21). A false-negative TST result may occur in patients with recent tuberculosis infection, overwhelming active tuberculosis infection, recent viral infections, or severe immunocompromise (AIDS) and in those younger than 6 years. Patients with remote exposure to M. tuberculosis may initially have a negative TST result that can become positive several weeks later after a second TST, known as the “booster effect.” The second test is recommended in health care workers 7 to 21 days after initial testing and should be performed on the opposite forearm; it is not required if IGRA is used. IGRAs are recommended in nearly all clinical settings in which TST is recommended; one exception is children younger than 5 years, for whom experts recommend both tests to increase specificity.

Diagnosis of Active Tuberculosis Infection

The CDC recommends AFB smear microscopy in all patients suspected of having active pulmonary tuberculosis. In vitro fluorescence microscopy of sputum is the preferred methodology. Testing three specimens is highly recommended because false-negative results from a single specimen are not uncommon. However, false-positive results are also not uncommon, thus a positive smear result requires mycobacterial culture confirmation. At least 3 mL of sputum should be submitted, although 5 to 10 mL is preferred. Serial specimens must be obtained at least 8 hours apart, and one must be an early morning specimen. Sputum induction is preferable to bronchoscopy as the sample methodology because of its greater sensitivity in patients who are unable to expectorate sputum.

The gold standard for diagnosis of active M. tuberculosis infection remains the mycobacterial culture. Whether AFB staining results are positive or negative, liquid and solid cultures should be performed for every specimen obtained. Liquid culture allows for faster growth and more rapid identification of organisms (2-4 weeks).

When a sputum smear result is positive for AFB, nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is highly recommended to verify the organism. The positive predictive value of a NAAT on a smear-positive sputum sample is 95%. In patients with an intermediate to high level of suspicion for active disease who have a negative smear, the NAAT result will be positive in 65% of cases. If available, a NAAT assay that also detects for rifampin resistance is recommended for timely detection of rifampin resistance. Although the NAAT assays are quick and sensitive, mycobacterial cultures are still recommended for performance of in vitro susceptibilities to all antimicrobial agents. It is important to note that a negative NAAT result cannot be used to exclude pulmonary tuberculosis; NAAT can rapidly confirm the presence of M. tuberculosis in 50% to 80% of AFB smear-negative, culture-positive specimens. Moreover, NAAT can facilitate earlier decision making regarding whether to initiate tuberculosis therapy.

If signs of extrapulmonary infection are present, samples from those areas should be obtained and sent for AFB stain, mycobacterial culture, and histopathology. Histopathology may be beneficial by demonstrating caseating granulomas, which are suggestive for but not exclusive to or diagnostic of tuberculosis. In disseminated tuberculosis, blood cultures for mycobacteria using isolator methodology are helpful.

Radiographic Procedures

The classic radiographic finding in pulmonary tuberculosis is that of upper lobe disease with air space disease and cavities. However, any radiographic pattern can be seen, from a “normal chest radiograph” or a solitary pulmonary nodule to diffuse alveolar infiltrates with acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Management

The primary goals of therapy include preventing additional morbidity, preventing mortality, and disrupting transmission of M. tuberculosis by eradicating the infection. When suitable antimicrobial therapy is administered and taken appropriately, clinical trials demonstrate clinical and microbiologic cure rates of approximately 95%. Therapy depends on several factors, including the classification of infection (latent versus active), pulmonary versus extrapulmonary infection, and patient adherence.

Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis

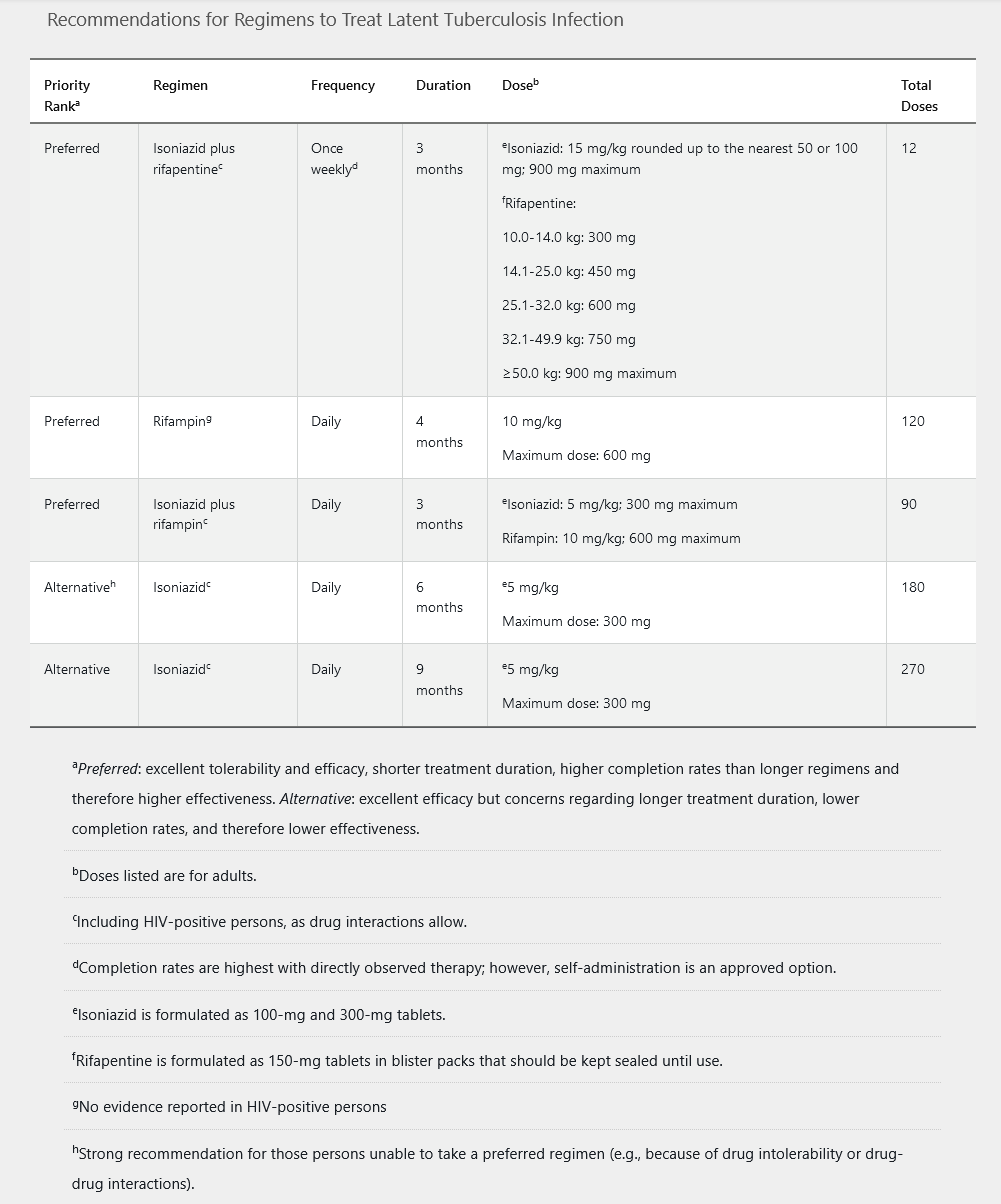

Patients who have a positive IGRA or a positive TST result should be evaluated for active disease with a full medical history, physical examination, and chest radiography. If no sign of active infection is present, all patients should be offered treatment for LTBI. CDC guidelines include five different treatment regimens (Table 22). Pyridoxine is recommended in patients who will receive isoniazid and are at risk for peripheral neuropathy (diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, malnutrition, HIV, and alcoholism). Baseline and monthly monitoring of liver chemistry tests are not routinely required unless patients are at risk for hepatotoxicity (HIV infection, chronic hepatitis B or C, alcohol abuse, pregnancy, concurrent hepatotoxic drugs, or underlying liver disease).

In pregnant women with LTBI, a 6- to 9-month regimen of isoniazid plus pyridoxine may be offered; however, some experts prefer to defer therapy until after delivery, unless the patient is at high risk of developing active infection owing to immunocompromise, including HIV infection.

Treatment of Active Tuberculosis

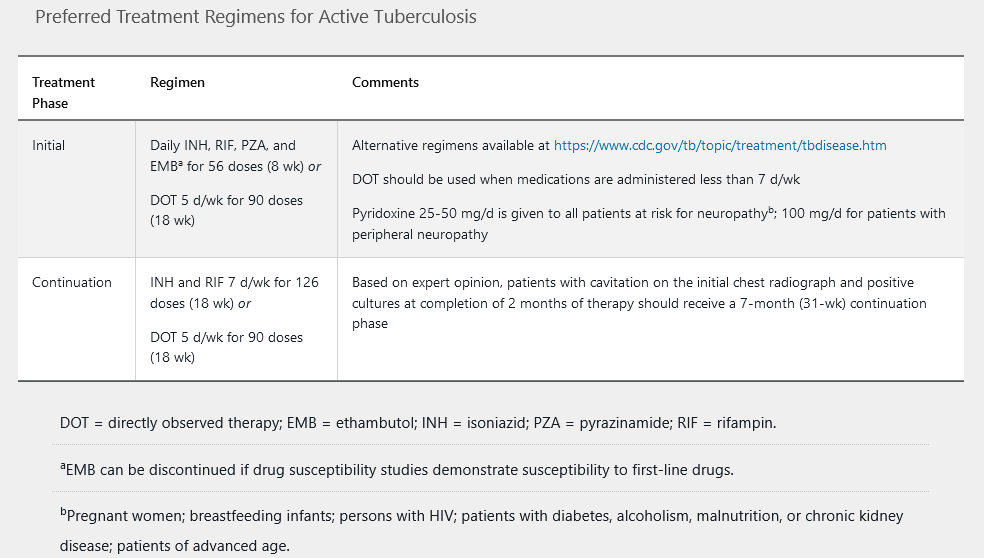

When active tuberculosis is verified, in vitro susceptibility testing of the initial isolate should be done for the first-line agents (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol). This becomes increasingly important because of the advent of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. If rifampin resistance has been detected during NAAT assessment, in vitro susceptibilities to first-line and second-line agents should be performed (Table 23).

The American Thoracic Society/CDC guidelines published in 2016 recommend 6 to 9 months of treatment in patients with drug-susceptible active tuberculosis. A four-drug regimen is given daily for 2 months, followed by a continuation phase of isoniazid plus rifampin daily, usually for 4 months (Table 24).

Directly observed therapy, generally through the local health department, is recommended for the treatment of active tuberculosis. Sputum specimens should be evaluated at 1- and 2-month intervals to assess for efficacy. In addition, clinical assessment and laboratory testing (complete blood count, liver chemistry testing, hepatitis serology) should be performed before initiating therapy.

It is essential to advise the patient of the possible adverse effect profiles of the various medications (see Table 23). In several studies, approximately 15% to 25% of patients receiving the four-drug regimen experienced some type of adverse effect. Most adverse effects are mild, and therapy may be continued; up to 15% are severe enough that therapy must be discontinued temporarily. If a hypersensitivity reaction is observed, then all four drugs should be discontinued and rechallenged sequentially to determine the cause.

Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

M. tuberculosis resistance to individual drugs arises by spontaneous point mutations. Depending on the resistance, the regimen must be altered in consultation with an expert. Only regimens including drugs to which the patient's M. tuberculosis isolate has a documented or high likelihood of susceptibility should be used. Drugs known to be ineffective based on in vitro growth or molecular resistance should not be used. In those with isoniazid- and rifampin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), at least a five-drug regimen should be provided for 5 to 7 months after culture conversion, followed by a four-drug regimen for a total treatment duration of 15 to 21 months (see Table 23).

Tuberculosis in patients with HIV infection may be complicated by immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Although the general recommendations for treatment are the same, antiretroviral therapy should be initiated within 2 weeks for patients with a CD4 cell count less than 50/µL and by 8 to 12 weeks for those with CD4 cell counts of 50/µL or more. An exception is HIV-positive patients with tuberculous meningitis, in whom antiretroviral therapy should not be initiated during the first 8 weeks of tuberculosis therapy regardless of the CD4 cell count to avoid increased morbidity because of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonist and Tuberculosis

Patients being treated with a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (such as infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, or certolizumab) have been reported to have an increased risk of reactivation to active infection or death from disseminated disease. It is recommended that these patients be evaluated for active or latent tuberculosis by performing chest radiography and simultaneous TST or IGRA. All patients should receive treatment for LTBI if identified, although LTBI treatment does not completely eliminate risk for active mycobacterial infection in this population.

Prevention

From the public health perspective, the best way to prevent tuberculosis is to diagnose, isolate, and treat infection rapidly until patients are considered noncontagious and the disease is cured. In the hospital, this means having a high index of suspicion for M. tuberculosis in high-risk groups and initiating immediate airborne isolation in negative pressure rooms (airborne infection isolation rooms) until the diagnosis can be excluded.

Recent CDC guidelines recommend criteria to determine that a patient is no longer contagious and a possible public health threat. These include appropriate antimicrobial therapy for at least 2 weeks, clinical improvement of signs and symptoms, and three negative sputum smears collected at least 8 hours apart, with one being an early-morning specimen. Patients with negative smear results are less contagious, although they may still have tuberculosis.

The BCG vaccination is a live-attenuated vaccine derived from an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis. It has been in use for more than 90 years throughout the world, although it is not routinely used in the United States. It is recommended for use at birth in countries with high rates of M. tuberculosis. In several international studies, the BCG vaccine has been shown to be effective in preventing severe infection, including meningitis in children. However, the efficacy in adults has not been established. CDC guidelines do not recommend the vaccine in the United States; however, the World Health Organization still recommends its use in high-prevalence areas.