Multiple Myeloma and Related Disorders

- related: Hemeonc

- tags: #hemeonc

Overview

B-cell maturation to plasma cells involves early antigen-independent and antigen-dependent phases. When humoral immunity is stimulated by an infection or inflammation, multiple clones of plasma cells are expanded. These plasma cell clones can produce immunoglobulins of different classes and specificity, giving the characteristic polyclonal spike seen on protein electrophoresis. In contrast, plasma cell dyscrasias (PCDs) or monoclonal gammopathies have clonal expansion of the plasma cell or lymphoplasmacytic cells, which produce the characteristic monoclonal spike (M spike) on protein electrophoresis. This monoclonal (M) protein can be a complete immunoglobulin, with a heavy chain (IgG, IgA, IgD, or IgM) complexed with a light chain (κ or λ), or free light chains (FLCs) without a heavy chain component. Various PCDs have been described (Table 6). Note that M spike denotes the presence of M protein, whereas IgM is the immunoglobulin M.

Evaluation for Monoclonal Gammopathies

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) occurs in approximately 3% of persons older than 50 years, and most remain asymptomatic without progression. It is a clonal premalignant disorder with low risk of conversion to other PCDs. Testing is typically restricted to patients with symptoms and signs of PCD (Table 7).

The M protein in PCDs can be detected by serum or urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP and UPEP). Occasionally, the M protein is not a full immunoglobulin but rather isolated light chains (κ or λ) that might be missed on protein electrophoresis. SPEP and UPEP can be good initial screening tests to identify and quantify the presence of an M spike, and the serum FLC assay is a sensitive test to identify and quantify FLCs in the serum. Neither SPEP nor UPEP can identify the subtype of immunoglobulin in the M spike, and both may miss small M proteins. Serum and urine immunofixation are more sensitive tests that can subtype the immunoglobulin and differentiate a monoclonal spike from a polyclonal spike. Polyclonal spikes are commonly found in infections, inflammatory processes, and chronic liver disease and do not usually require further hematologic evaluation. Serum FLC testing detects light chains that are not bound to heavy chains and helps quantify them. In inflammatory and infectious processes, κ and λ FLCs are increased, but the ratio remains normal because they increase proportionately. In patients with a PCD, the clonal plasma cells secrete one type of FLC, leading to an increase in the involved light chain and an abnormal FLC ratio. SPEP, serum immunofixation, and serum FLC testing are commonly used for the initial evaluation of PCDs.

Although MGUS and multiple myeloma are common causes of abnormal M proteins, other disorders can also produce an M spike (see Table 6), and patients should be evaluated for the signs and symptoms of these diseases (see Table 7). Tests considered during the evaluation of monoclonal gammopathies include complete blood count with differential; serum chemistries, including creatinine, calcium, and albumin levels; β2-microglobulin; SPEP; UPEP; serum and urine immunofixation; serum FLC tests; and quantitative immunoglobulins. Plain radiographs of the bones (skeletal surveys) are used to assess for the presence of lytic lesions. Skeletal surveys are used to assess for lytic lesions in multiple myeloma. Bone scans, which detect increased osteoblast activity in most bone metastases, may not detect the more purely lytic lesions in multiple myeloma and should not be used. In select patients, PET scans and MRI are required to accurately evaluate bone lesions.

Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy quantifies the percentage of plasma cells in the marrow and help classify the PCD. Cytogenetic evaluation of the bone marrow aspirate helps establish an accurate prognosis. Bone marrow testing can be deferred in patients with low-risk features, such as an IgG gammopathy measuring less than 1.5 g/dL, a normal serum FLC ratio, and no evidence of end-organ damage.

Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance

MGUS is characterized by an M protein level less than 3 g/dL (or less than 500 mg/24 h of urinary monoclonal FLCs), clonal plasma cells comprising less than 10% of the bone marrow cellularity, and the absence of related signs and symptoms of end-organ damage (Table 8). MGUS is diagnosed incidentally during evaluation for various signs and symptoms such as neuropathy, vasculitis, elevated protein, or end-organ damage.

The prevalence of MGUS increases with age and is noted in approximately 5% of persons older than 70 years. When an asymptomatic condition has a high prevalence rate and low risk of progression to symptomatic disease, it is important to provide an accurate prognosis and appropriate counseling and management. Non-IgM, IgM, and light-chain MGUS are the three types, based on type of M protein. Non-IgM MGUS can progress to multiple myeloma and, although less likely, to other PCDs at a rate of 1% per year. IgM MGUS has the potential to progress to Waldenström macroglobulinemia at a rate of 1.5% per year. Light-chain MGUS can progress to other PCDs at a rate of 0.3%. In addition to the type of M protein, factors that predict the risk of progression include the quantity of M protein and an abnormal serum FLC ratio (Table 9).

In addition to the risk of progression, patients with MGUS are at higher risk of osteoporosis and fracture of the axial skeleton, and bone mineral density testing should be considered. Treatment is not required at diagnosis. Patients commonly undergo follow-up for signs and symptoms of progression, initially at 6 months and then yearly, if stable.

Kidney disease in patients with monoclonal gammopathy has traditionally been linked to light-chain nephrotoxicity in those with multiple myeloma or amyloid infiltration in those with amyloidosis. More recent data suggest that some patients with features otherwise quite consistent with MGUS may, nonetheless, have significant kidney disease related to the abnormal immunoglobulin. If other, more likely causes of kidney injury are excluded (for example, diabetes or hypertension), these patients should be diagnosed with monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance and require aggressive myeloma-like therapy to prevent progressive and irreversible kidney injury.

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a clonal plasma cell neoplasm. MM can present as smoldering (asymptomatic) disease with risk of progression or as symptomatic disease, which requires immediate treatment to prevent complications. Smoldering MM has a higher clonal plasma cell burden than MGUS and a higher risk of transformation to MM requiring therapy.

Clinical Manifestations and Findings

MM requiring therapy can manifest with classic symptoms such as hypercalcemia, kidney disease, anemia, and bone disease (see CRAB criteria in Table 8). Other possible symptoms include fatigue, weight loss, neuropathy, and those arising from extramedullary plasmacytoma.

Normocytic anemia is a common finding in MM requiring therapy. Anemia is caused by bone marrow plasma cell infiltration and kidney disease. The peripheral blood smear may show rouleaux formation (Figure 5). Patients can also be immunosuppressed from leukopenia, impaired lymphocyte function, and hypogammaglobulinemia. Although patients with MM can have increased total immunoglobulin, normal immunoglobulins are usually reduced. Patients are at increased risk of respiratory infections, and chemotherapy for MM can further increase this risk.

Bone pain is a common symptom of MM. Osteoclast activation and osteoblast inactivation occur, leading to development of lytic lesions (Figure 6) and vertebral body compression fracture. This increased bone resorption leads to hypercalcemia. Patients with MM are prone to developing pathologic fractures with minimal or no trauma.

Kidney dysfunction with an elevated creatinine level or occult injury is seen in a significant proportion of patients. The two main causes of kidney disease are elevated FLCs causing cast nephropathy and hypercalcemia. Cast nephropathy, commonly termed myeloma kidney, is caused by deposition of FLCs in the distal tubules, leading to tubulointerstitial damage. Underlying cast nephropathy makes these patients especially vulnerable to additional kidney injury through dehydration, NSAID use, or exposure to radioiodine contrast. Other causes of kidney dysfunction in MM include immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis, cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis, and proximal tubulopathy.

Diagnosis and Prognosis

Diagnostic criteria for MM are listed in Table 8. Evaluating patients with suspected MM includes identification of the M protein, assessment for symptoms of MM, and determination of whether these symptoms are attributable to MM. Identification and quantification of the M protein are accomplished with SPEP, UPEP, and serum FLC testing (see previous section, Evaluation for Monoclonal Gammopathies). Bone marrow biopsy is performed to evaluate the plasma cell burden and to determine cytogenetics for risk stratification. All patients are evaluated for laboratory features of MM with complete blood count, serum creatinine and calcium levels, and skeletal surveys following the CRAB criteria outlined previously. Plain radiography can detect most bone lesions in MM, but in select patients with negative skeletal surveys and with bone symptoms, a CT or MRI is performed (whole-body MRI is preferred). PET-CT is routinely performed during the evaluation of a patient with plasmacytoma to assess the presence of additional occult extramedullary tumors.

Symptoms of organ dysfunction should not necessarily be attributed to the underlying PCD. Kidney biopsy is performed to document myeloma kidney when it is clinically difficult to differentiate kidney injury from another diagnosis, such as diabetic nephropathy. Evaluation for alternative causes of hypercalcemia and anemia should be completed, especially when the patient has low-risk disease.

Smoldering MM has a risk of conversion to MM requiring therapy of about 10% per year for the first 5 years. The risk of progression decreases after the first 5 years. This risk is not uniform; risk factors for progression include a high M protein level, a large burden of clonal plasma cells, and an abnormal serum FLC ratio (see Table 9). Patients with smoldering MM at imminent risk of progression in the next 2 years and therefore requiring immediate therapy include those with 60% or more plasma cells in the bone marrow, more than one focal bone lesion on MRI, or a serum FLC ratio of 0.01 or less or 100 or greater.

MM is staged based on serum markers such as β2-microglobulin and albumin. However, cytogenetics of the bone marrow more accurately predict prognosis and sometimes guide better treatment decisions.

Treatment

Patients with smoldering MM are usually monitored for progression to MM requiring therapy every 3 to 6 months without beginning treatment. Recent studies have shown improved survival with treatment of high-risk smoldering MM; however, defining these patients at high risk is somewhat controversial, and it is not routine practice to treat them. Bisphosphonates do not decrease the risk of progression in smoldering MM.

Treatment of MM requiring therapy has been revolutionized over the last few years with the advent of new treatment options, which have significantly improved survival (averaging almost 10 years from diagnosis). Patients are initially evaluated for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) eligibility. Autologous HSCT with high-dose melphalan is not curative in MM but does improve progression-free and overall survival. Patients eligible for transplant typically undergo induction therapy with multiagent chemotherapy followed by autologous HSCT and close observation or maintenance therapy. Induction chemotherapy involves various combinations of immunomodulatory drugs (lenalidomide or thalidomide), proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib), glucocorticoids (dexamethasone), and alkylating agents (melphalan or cyclophosphamide).

Treatment for MM is not curative, so all patients eventually present with relapsed or refractory disease. Several new drugs have been approved in this setting, including proteasome inhibitors (carfilzomib and ixazomib), the immunomodulatory drug pomalidomide, histone deacetylase inhibitors (panobinostat), and monoclonal antibodies (daratumumab and elotuzumab). These new agents are effective, and studies are under way evaluating them in the first-line setting.

Agents used to treat MM have unique side effects. Lenalidomide and pomalidomide carry a risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), and patients are considered for thromboprophylaxis. Bortezomib and thalidomide cause peripheral neuropathy. Bortezomib is associated with a high risk of herpes zoster reactivation; prophylactic therapy with acyclovir is recommended.

Pain is a dominant symptom in patients with MM requiring therapy, and many patients require treatment with opioids; NSAIDs can worsen kidney disease in these patients. Surgical stabilization of impending fracture is undertaken to prevent morbidity. Bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid and pamidronate) are used to prevent skeletal events. Zoledronic acid has also been shown to improve survival in MM requiring therapy. Patients taking bisphosphonates should be closely monitored for hypocalcemia and osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Nephrotoxic agents and contrast studies should be used judiciously in patients with MM and a risk of worsening kidney disease. Hypercalcemia is treated with hydration and bisphosphonates. Annual influenza vaccination (inactivated) should be administered to all patients with MM. Because of the immunocompromised state of MM, pneumococcal vaccination with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine should be administered in accordance with Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidelines (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine). Select patients with recurrent infections and hypogammaglobulinemia benefit from intravenous immune globulin infusions.

Immunoglobulin Light-Chain Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis refers to a varied group of disorders associated with extracellular deposition of low-molecular-weight proteins in a β-pleated sheet configuration. These are usually abnormal proteins that circulate in the blood and deposit in various organs. Various proteins have been implicated in amyloidosis (Table 10). All amyloid deposits have a characteristic apple-green birefringence under polarized light microscopy of the tissue with Congo red staining.

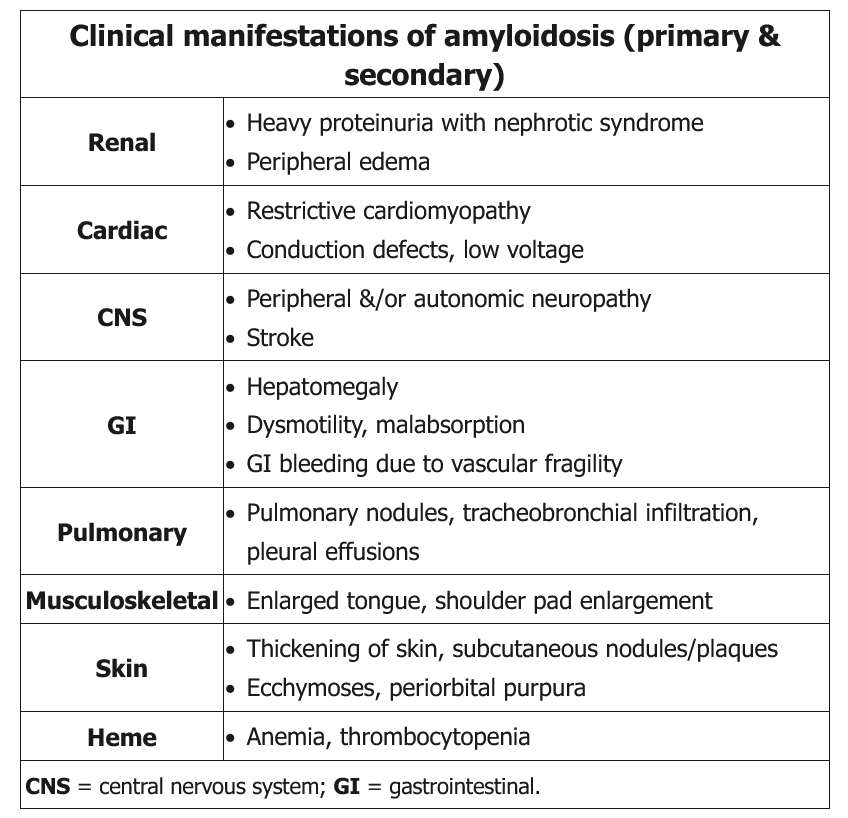

Light-chain amyloidosis (AL) is the most common type. It is a clonal plasma cell dyscrasia characterized by production of amyloidogenic λ or κ free light chains. These light chains can deposit in various organs, resulting in varying clinical presentations of the disease (Table 11, Figure 7). Diagnosis requires biopsy of the affected tissue that shows the characteristic pathological findings. To avoid invasive biopsy, fat pad or bone marrow biopsy is sometimes performed initially. After confirmation of the amyloid in the tissue, immunohistochemical staining can confirm the light-chain composition of the amyloid deposit or identify alternative components, such as transthyretin or amyloid A protein. Patients with AL amyloidosis should undergo analysis for clonal plasma cell dyscrasias with serum and urine protein electrophoresis, serum FLC testing, and bone marrow biopsy.

All patients are evaluated for extent of organ involvement. Cardiac involvement is common with AL amyloidosis, and evaluation with echocardiography, electrocardiography, B-type natriuretic peptide, and serum troponin T is commonly performed. Cardiac MRI is more sensitive than echocardiography and has a distinctive pattern. Kidney involvement usually manifests as nephrotic range proteinuria; 24-hour urine assessment of the protein assists diagnosis. Other organs that can be involved and their clinical features are listed in Table 11.

Prognosis of AL amyloidosis depends on the presence and extent of cardiac involvement; survival ranges from almost 8 years to only 6 months.

Treatment of AL amyloidosis starts with evaluating the patient for autologous HSCT. Eligibility for transplantation is based on age (younger than 70 years), performance status (independence completing activities of daily living), and the extent of organ involvement. Patients with advanced cardiac disease, stage 4 chronic kidney disease, or large effusions are generally not eligible for transplantation. Autologous HSCT has been shown to improve organ function and survival. Patients ineligible for transplant should receive treatment with melphalan- or bortezomib-based chemotherapy regimens. Supportive care to treat symptoms is necessary.

Waldenström Macroglobulinemia

Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) is an indolent B-cell lymphoma with clonal lymphoplasmacytic cells in the bone or lymph nodes that secrete clonal IgM in the blood. WM is differentiated from MGUS by the presence of more than 10% clonal lymphoplasmacytic cells in the bone marrow, greater than 3 g/dL of M protein, symptoms from the disease, or a combination of the three. As in multiple myeloma, patients with smoldering, asymptomatic WM can be observed without therapy.

Patients can present with classic “B symptoms” of drenching night sweats, fever, and weight loss and may have anemia and fatigue. Tissue infiltration leads to hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and kidney disease. Peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy is seen in 20% of patients and can be associated with antimyelin-associated glycoprotein. Increased serum viscosity from the circulating IgM can lead to hyperviscosity syndrome. Hyperviscosity syndrome can include diverse central nervous system symptoms, including headache, altered mental status, change in vision and hearing, nystagmus, and ataxia. Funduscopic evaluation may reveal dilated retinal veins, papilledema, and flame hemorrhages. Mucosal bleeding is related to platelet dysfunction and dysfibrinogenemia (prolonged thrombin time).

Other common findings include "sausage link" retinal veins, markedly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and rouleaux formation on peripheral blood smear.

Symptomatic hyperviscosity requires emergent treatment with plasmapheresis to remove excess IgM. Therapy to decrease IgM production is instituted simultaneously in patients with hyperviscosity symptoms and should be initiated in other patients with symptomatic WM. Rituximab, either as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy such as cyclophosphamide, bendamustine, and bortezomib, along with glucocorticoids, is commonly used. Recently, ibrutinib (a Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor) has been approved for treatment of WM.

Cryoglobulinemia

Cryoglobulinemia denotes the presence of clonal or polyclonal immunoglobulins that precipitate in the serum at temperatures less than 37 °C (98.6 °F) and dissolve with rewarming. Cold agglutinins, which are often confused with cryoglobulins, are antibodies against erythrocyte antigens that agglutinate erythrocytes in blood at temperatures less than 37 °C (98.6 °F) and can sometimes cause cold agglutinin autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Cryoglobulinemias are classified as types I, II, and III based on the composition of the cryoglobulins. Type I cryoglobulinemia involves a monoclonal immunoglobulin, usually IgM, and is associated with plasma cell dyscrasias. Types II and III are called mixed cryoglobulinemias; they are composed of a mixture of polyclonal IgG and monoclonal or polyclonal IgM. Mixed cryoglobulinemias are usually seen in association with infections such as hepatitis C, with connective disorders, and rarely with lymphoproliferative disorders.

Type I cryoglobulinemia is usually asymptomatic but can rarely cause symptoms of hyperviscosity and thrombosis. Patients can present with digital cyanosis, ulcers, Raynaud phenomenon, or gangrene. Patients with neurologic symptoms from the hyperviscosity are treated with emergent plasmapheresis, along with treatment of the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia to prevent production of cryoglobulins. Vasculitic symptoms, such as palpable purpura, glomerulonephritis, and neuropathy, are less common in type I (see MKSAP 18 Rheumatology for further information on mixed cryoglobulinemias).