Mitral Stenosis

Mitral stenosis is narrowing of the mitral valve due to calcification or valvular damage that results in an increased pressure gradient between the left atrium and left ventricle.

Mitral stenosis results in increased left atrial pressures which are eventually transmitted to the pulmonary venous circuit.

Almost all cases of mitral stenosis are secondary to rheumatic heart disease, an autoimmune condition which results in scarring and narrowing of the valve with eventual fusion of the commissures. This is sometimes called a “fish mouth” valve.

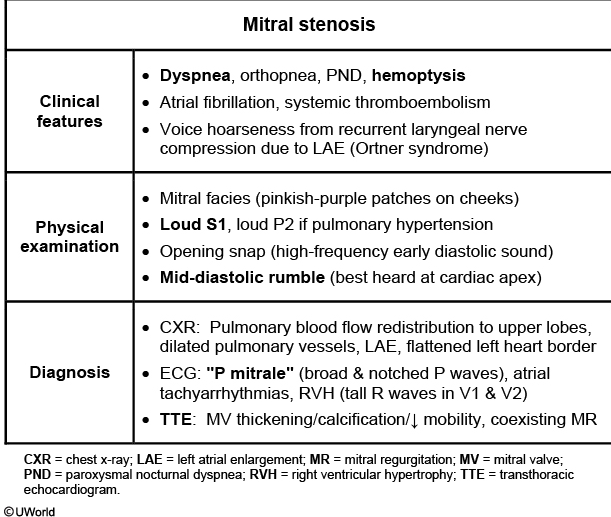

Symptoms and PE

Backup behind the stenotic mitral valve eventually involves the pulmonary venous vasculature, leading to **exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, **and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

Hemoptysis due to mitral stenosis can occur if the increased pulmonary circuit pressures rupture small pulmonary vessels, spilling blood into the alveoli.

Symptoms are exacerbated by increased cardiac demand.

On auscultation a low-pitched diastolic rumble following an opening snap just after the second heart sound is heard best at the fourth intercostal space, midclavicular line, with the patient in left lateral decubitus position. The murmur is often followed by a loud S1.

The time between the opening snap and the second heart sound decreases as the stenosis becomes more severe. Patients may have a loud first heart sound by comparison.

Diagnosis

Chest X-ray will demonstrate an enlarged left atrium with straightening of the left heart border, pulmonary congestion and elevation of the mainstem bronchus due to mass effect of the enlarged atrium. Lateral chest x-ray projection can reveal posterior displacement and impingement of the esophagus.

Echocardiography is necessary to confirm and stage disease

- Pressure gradient

- Valve area

- Valve score (0-16) based on leaflet mobility and thickening, subvalvular thickening, and calcification

Mitral stenosis may cause right-sided heart failure or stroke.

Thromboembolic stroke secondary to mitral stenosis may occur if the dilated atrium causes atrial fibrillation, leading to stagnant blood that forms a mural clot (often in the left atrial appendage).

Right sided heart failure can result from mitral stenosis when the pressure backup behind the stenotic valve extends into the pulmonary circuit and causes the pulmonary vasculature to constrict, leading to pulmonary hypertension.

Treatment

Initial management of mitral stenosis involves the use of medications to reduce intravascular volume with the goal of reducing pulmonary vascular congestion.

Loop diuretics and salt restriction are used to relieve symptoms of pulmonary congestion, and β-blockers may help relieve dyspnea. Anticoagulation with warfarin is indicated for patients with atrial fibrillation, atrial thrombus, or a previous embolic event.

Surgical management is indicated for severe disease:

- Heart failure symptoms with mitral valve area (MVA) <1.5cm2

- Heart failure symptoms with MVA >1.5 but increased PASP/PCWP

- Change in pressure gradient across MV with exercise

- Asymptomatic patients with MVA<1.5 and pulmonary HTN

Options for surgery include percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty (balloon open the valve) or (when contraindicated) open commissurotomy (open surgery) and mitral valve replacement.

Mitral stenosis is no longer considered a high risk heart condition which requires antibiotic prophylaxis for things like dental procedures. An exception to this would be if a patient with mitral stenosis has a history of infective endocarditis.

This patient's presentation suggests likely mitral stenosis (MS) due to rheumatic heart disease. There is often a latency period of 10-20 years between the initial episode of symptomatic MS, with most patients manifesting during the 4th or 5th decade of life.

Common symptoms include dyspnea (70% of patients), fatigue, atrial fibrillation, and thromboembolism (eg, stroke). Hemoptysis (from pulmonary edema or pulmonary apoplexy) and hoarseness (due to compression of recurrent laryngeal nerve by enlarged left atrium) may occur. Pregnant women with MS are at risk for atrial fibrillation and pulmonary edema due to physiologic hypervolemia and increased left atrial and pulmonary venous pressure. Advanced disease may lead to right-sided heart failure (eg, edema, pleural effusions, hepatic congestion). Cardiac auscultation may show the classic MS murmur, a low-pitched diastolic rumble most prominent at the apex. Other findings include loud 1st heart sound (S1), loud pulmonic (P2) component of second heart sound (due to pulmonary hypertension), and normal apical impulse.

tation and typical demographics; it is further confirmed by classic findings from physical examination and diagnostic evaluation.