MKSAP Transfusion Medicine

- related: Hemeonc

- tags: #hemeonc

Clinical trials supporting the benefits of a more cautious transfusion strategy have dramatically changed transfusion practice. For elective transfusions, ABO and Rh matching based on a properly labeled blood specimen remains the cornerstone of safe transfusion. Approximately 5% to 10% of hospitalized patients have evidence of erythrocyte alloimmunization from previous transfusions, pregnancy, or organ transplantation. These antibodies to non-ABO blood group antigens pose a risk for delayed (as opposed to acute) hemolytic transfusion reaction. Other noninfectious risks of transfusion, such as transfusion-associated circulatory overload, are now better recognized. Although the traditionally feared infectious risks of transfusion, hepatitis C virus and HIV, are now quite rare, transfusions are linked to an evolving spectrum of emerging infectious diseases, such as Zika virus.

Blood Donor Screening

Blood donor screening comprises questions to establish the general health of the donor and exclude high-risk behaviors or potential exposures that increase the risk of transfusion-transmitted infection, followed by selected laboratory testing. The hemoglobin level cutoff is 12.5 g/dL (125 g/L) for women, which excludes a small proportion of otherwise healthy women from donating. Most platelets transfused in the United States are collected from donors by apheresis, which increases platelet yield but is a more time-consuming procedure than whole blood donation. Laboratory testing of whole blood and platelet donations includes screening for hepatitis B and C viruses, HIV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus I/II, and West Nile virus; serologic testing for syphilis; and, in select regions of the country, testing for antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi (agent for Chagas disease), Babesia, and most recently, Zika virus. Platelet components are also screened for bacterial contamination before being released for transfusion.

Blood Group Antigens, Pretransfusion Compatibility Testing, and the Direct Antiglobulin Test

A “type and screen” comprises ABO/Rh blood group determination and a screening test for unexpected (non-ABO) antibodies. A “type and cross” uses patient plasma or serum to crossmatch against a representative sample from a donor erythrocyte unit for transfusion. For procedures in which blood transfusion is not invariably needed, a type and screen showing no unexpected antibodies eliminates the need for specific crossmatching; blood can be quickly crossmatched when and if the decision to transfuse is made. Rh-positive persons can receive Rh-positive or Rh-negative blood. Rh-negative persons should receive only Rh-negative blood, except in circumstances of massive transfusion (such as gastrointestinal bleeding or traumatic hemorrhage), when Rh-positive blood can be given to preserve the inventory of scarcer Rh-negative units. Rh-positive blood should never be given to persons already sensitized to Rh antigens or to Rh-negative women of childbearing potential because exposure increases their risk for subsequent pregnancies affected by hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Plasma requires ABO but not Rh matching; platelets, with some exceptions, are not ABO or Rh matched.

A direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test is performed to look for IgG or complement coating a patient's erythrocytes and is part of the investigation for suspected hemolytic transfusion reactions (acute or delayed), autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and hemolytic disease of the newborn.

Blood Components

Packed Red Blood Cells

Packed red blood cells (PRBCs), which contain a small amount of residual plasma, are suspended in anticoagulant-preservative solution at a hematocrit level of 55% to 65%. Transfusion of one unit of PRBCs to an average-sized nonbleeding adult raises the hematocrit level by 3% and the hemoglobin level by 1 g/dL (10 g/L). Erythrocyte transfusion to patients with anemia increases oxygen-carrying capacity; the threshold for transfusion varies according to the chronicity of the anemia and the patient's comorbidities.

Plasma

Plasma contains coagulation factors, albumin, immunoglobulins, and other plasma proteins. Plasma transfusion is indicated to restore coagulation factors for which specific factor concentrates are not available or in the setting of multiple acquired deficiencies, as in disseminated intravascular coagulation. If frozen within 6 hours of collection, the product is called “fresh frozen plasma” and has a shelf life of 1 year at −20 °C (−4 °F), or 24 hours after it is thawed at 37 °C (98.6 °F). Thawed fresh frozen plasma can be relabeled as thawed plasma, extending its shelf life to 5 days of storage. Although thawed plasma has lower levels of labile factors, such as factors V and VIII, the difference is not clinically significant in most transfusion situations, particularly because factor VIII is an acute phase reactant.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate is the small fraction of plasma that precipitates when fresh frozen plasma is thawed at 1 to 4 °C (33.8-39.2 °F). It contains mostly fibrinogen and factor VIII and is most often used in conditions associated with hypofibrinogenemia, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation. It is also sometimes used empirically in uremic bleeding, but the mechanism of action is poorly understood. For adult patients who require fibrinogen replacement, multiple (8-10) units of cryoprecipitate (from 8-10 donors) must be pooled together.

Platelets

A unit of platelets is suspended in plasma and has a short shelf life of 5 days at 20 to 24 °C (68-75.2 °F). Platelets can be made from a whole blood donation (a platelet concentrate) or collected by apheresis. A bag of apheresis platelets provides a platelet dose equivalent to 4 to 6 units of platelet concentrate and raises the platelet count of an average-sized adult by 20,000 to 25,000/µL (20-25 × 109/L) (for example, from a platelet count of 10,000/µL to 30,000/µL). Platelets are not generally indicated in patients with thrombocytopenia in the absence of trauma, surgery, or bleeding until the platelet count decreases to less than 10,000 to 20,000/µL (10-20 × 109/L); the lower platelet count is more applicable to patients with chronic thrombocytopenia who are otherwise stable. The transfusion threshold for patients with bleeding, trauma, or both, is approximately 50,000/µL (50 × 109/L).

PRBCs and platelet components can be modified through processes such as leukoreduction, irradiation, and washing, which are indicated in special transfusion circumstances (Table 24).

Plasma Derivatives

Plasma pooled together from thousands of donors is fractionated into derivatives such as albumin (used for oncotic pressure in hypotensive patients or after large volume paracentesis cirrhotic patients), intravenous immune globulin (for patients who have humoral immunodeficiencies), Rh immune globulins (for Rh-negative pregnant women to prevent sensitization from an Rh-positive fetus), or coagulation factor concentrates (such as factor VIII concentrate for von Willebrand disease) (Table 25). Plasma derivatives are processed to reduce the risk of infectious disease transmission. Recombinant factor concentrates (not containing any donor plasma) have become the standard of care for younger patients with hemophilia A and B (factor VIII and IX deficiency, respectively).

Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), specifically the newer generation of four-factor PCC, which contains factors II, VII, IX, and X, are the preferred product for patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding while taking warfarin anticoagulation. Previously, plasma transfusion with or without vitamin K supplementation was used with the attendant risks of volume overload and allergic reactions. Inappropriate use of PCCs carries a thrombotic risk, so they should not be used in patients who have elevated INRs from warfarin without life-threatening bleeding or before elective invasive procedures in patients receiving anticoagulation or patients with chronic liver disease. A recent multicenter trial demonstrated the safety and efficacy of PCCs compared with plasma transfusion in patients requiring urgent surgical interventions. PCCs contain residual heparin and are contraindicated in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Blood Management

Patient-centered blood management uses allogeneic blood components to achieve a clinically relevant goal rather than to correct an abnormal laboratory finding; identifies and corrects specific causes of anemia that eliminate the need for transfusion; and reduces iatrogenic blood loss by eliminating unnecessary phlebotomy for routine laboratory testing.

In the previous 2 decades, several large, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the safety of a restrictive transfusion threshold (hemoglobin level <7-8 g/dL [70-80 g/L]) compared with a more liberal threshold (hemoglobin level <9-10 g/dL [90-100 g/L]) in common clinical settings in which blood is transfused, such as in critically ill patients in the ICU, patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, and older adult patients after hip fracture surgery. With the exception of the “TITRe” trial in cardiac surgery, all the trials found that a restrictive transfusion threshold produced equivalent, and in some cases superior, outcomes, such as in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Incorporating restrictive transfusion guidelines in computerized physician order entry pathways increases adherence to these thresholds. Although a restrictive transfusion threshold has proven beneficial in many clinical scenarios, emergent transfusion at more liberal transfusion thresholds will remain important in specific instances, such as in patients with anemia and acute coronary syndrome or acute stroke and patients who are actively bleeding and hemodynamically unstable.

Transfusion Complications

Transfusion reactions occur in approximately 1% of transfusions. They are best classified according to the main presenting symptoms, such as fever and chills, respiratory distress, and allergic manifestations. Although fatal reactions are rare (incidence of 1:200,000-400,000 units), the leading causes are hemolysis, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and transfusion-associated circulatory overload.

Hemolytic Reactions

Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions

Acute hemolytic transfusion reactions result from clerical errors at the time of specimen collection or blood administration. Electronic barcode systems that print a specimen label from the patient's wristband on demand or verify patient-unit compatibility at the time of bedside transfusion reduce such errors but are not yet widely adopted. Patient and specimen identification can be particularly problematic in high turnover areas such as the emergency department or in mass-casualty incidents. Patients develop fever and flank pain and appear anxious and distressed. Hypotension and diffuse bleeding may be signs that acute hemolysis has triggered disseminated intravascular coagulation. Hemoglobinuria and hemoglobinemia may be noted. Platelets, because of their short shelf life, are administered in adult transfusion practice without regard to ABO compatibility, and, rarely, high-titer ABO antibodies in the plasma of group O platelets may mediate less extensive hemolytic transfusion reactions, which are more subtle and harder to recognize, such as an unexplained drop in hematocrit level or a newly positive direct antiglobulin test result. The most important step in managing signs or symptoms consistent with an acute hemolytic transfusion reaction is to stop the transfusion; outcomes worsen as more incompatible blood is transfused. Clerical review and blood bank notification should follow. Laboratory tests include the direct antiglobulin test, haptoglobin and plasma free hemoglobin measurements, and urinalysis to assess hemoglobinuria. Volume expansion and supportive care for associated complications (disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute kidney injury) are required.

Delayed Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction

Antibodies to non-ABO blood group antigens (so-called “minor” antigens) develop in some persons after transfusion or pregnancy but may be not be detectable when subsequent transfusion is needed years later. When re-exposed to transfused cells with the same antigen, an anamnestic antibody response leads to delayed hemolysis of the transfused antigen-positive erythrocytes, typically 7 to 14 days after the transfusion. The causative association between a hematocrit level decrease, often accompanied by low-grade fever, and a transfusion 1 to 2 weeks beforehand is not always appreciated, particularly in postoperative patients or patients discharged from the hospital. Investigation of a suspected delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction should include a direct antiglobulin test (and blood bank notification) and evaluation of markers of hemolysis, such as lactate dehydrogenase and bilirubin levels and reticulocyte count. Patients should be informed regarding their alloimmunization status so they can communicate this information to other health care providers for subsequent surgery or other care. Some jurisdictions outside the United States have transfusion “antibody registries” for this purpose.

Nonhemolytic Transfusion Reactions

Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is an underrecognized problem and may be the most common serious complication of blood transfusion, affecting 1% to 8% of transfusion recipients. Risk factors include older age, pre-existing cardiovascular or kidney disease, and rapid administration rate. Signs and symptoms include respiratory distress within 6 hours of transfusion, positive fluid balance, elevated central venous pressure, elevated B-type natriuretic peptide, and compatible radiographic findings of pulmonary edema. Therapy consists of diuretics and a slower rate of blood administration.

Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury

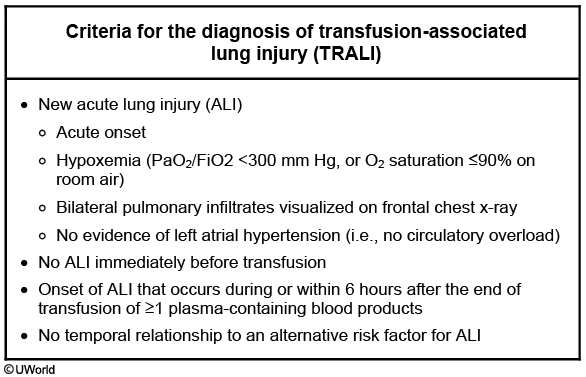

Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) is defined as noncardiogenic pulmonary edema that occurs within 6 hours of transfusion. These patients are more likely to present with fever and hypotension and less likely to have overt signs of volume overload as in patients with TACO. Radiographic findings usually suggest a noncardiac pulmonary edema or adult respiratory distress syndrome but may resemble those seen in TACO. Most cases of TRALI occur because of HLA or neutrophil-specific antibodies in multiparous donors that bind to and activate recipient leukocytes in the pulmonary vasculature. The incidence of this complication has been significantly reduced by screening donors for these antibodies.

Patients with TRALI usually present with sudden onset dyspnea, hypoxemia, and pulmonary infiltrates during or within 6 hours of any blood product transfusion (in the absence of circulatory overload). Chest x-ray shows bilateral patchy alveolar infiltrates consistent with ARDS. Importantly, TRALI diagnosis requires that patients not have preexisting ALI or other established ALI risk factors (e.g., septic shock, pneumonia, inhalation injury, etc.).

Management is supportive and includes supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilatory support as needed, and vasopressors for hypotension. This management is analogous to that used for other causes of adult respiratory distress syndrome, although the prognosis is better and the recovery quicker. TRALI is unlikely to recur in subsequent transfusions for individual patients.

Febrile Nonhemolytic Transfusion Reaction

Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction (FNHTR) is common, occurring in about 1% of transfusion episodes, and is mediated by proinflammatory cytokines elaborated by donor leukocytes during storage. Symptoms encompass a temperature increase of 1 °C (1.8 °F) to greater than 38 °C (100.4 °F) within 4 hours of transfusion or chills and rigors even in the absence of a fever. The differential diagnosis of fever occurring in association with transfusion includes hemolysis and septic transfusion reaction. Investigation consists of a direct antiglobulin test, visual inspection of patient plasma for hemolysis, and a clerical check and, if warranted, obtaining a blood bag culture and blood cultures from the patient. Although antipyretics are appropriate as therapy, no studies have shown that they prevent FNHTR, so routine prophylaxis with antipyretics is not warranted. Prestorage leukocyte reduction of whole blood by filtration at the blood center or at the time of platelet apheresis collection can prevent FNHTR.

Infectious Complications

Bacterial contamination of blood components occurs from inadequate cleansing of the donor's skin before phlebotomy or from occult (asymptomatic) bacteremia in the blood donor. Platelet components are screened for bacterial contamination before release for transfusion, but residual risk remains, typically for gram-positive organisms that are part of skin flora. Erythrocyte components, when contaminated, tend to contain gram-negative organisms such as Yersinia, which thrive in a cold and iron-rich environment. Infectious complications include the transmission of agents not routinely tested for, such as Babesia. The clinical features may include fever with or without hypotension.

Allergic Reactions and Anaphylaxis

Mild allergic reactions with pruritus and urticaria occur in 1% to 5% of recipients, during or after the transfusion of plasma-rich components (including platelets). If symptoms resolve after the administration of antihistamines, transfusion can be restarted with the same unit under close observation. The transfusion must be discontinued if symptoms recur or progress beyond urticaria. No evidence supports the routine use of antihistamine or glucocorticoid prophylaxis in patients with previous mild allergic transfusion reactions.

Anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions are rare. Manifestations include angioedema, stridor, abdominal symptoms, and hypotension. In addition to antihistamines (H1 and H2 blockers), patients may require bronchodilators, fluid resuscitation, and epinephrine. Investigation of possible underlying protein deficiency (IgA or haptoglobin) should be undertaken in a patient with an anaphylactic transfusion reaction. The documentation of severe IgA deficiency with anti-IgA antibodies necessitates the future use of washed cellular blood components or plasma components from IgA-deficient donors.

Transfusion-Associated Graft-versus-Host Disease

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease is a rare but fatal complication in which donor lymphocytes in a cellular blood product (erythrocytes or platelets) engraft in an immunocompromised recipient and cause toxic effects in the bone marrow, skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Patients at risk include those receiving chemotherapy for autoimmune disorders or malignancy, recipients of blood components from first-degree relatives, and premature infants. Prevention involves γ irradiation of cellular blood components intended for recipients at risk. Patients who have undergone stem cell transplantation typically require irradiated blood components indefinitely; this should be communicated from the transplant center at the time of discharge from the transplant program.

Transfusion in Special Circumstances

Massive transfusion refers to the transfusion of one total blood volume, which is equivalent to 8 to 10 units of blood, within a 24-hour period. Conditions requiring massive transfusion include trauma, ruptured aortic aneurysm, and severe gastrointestinal bleeding. When whole blood is lost and replaced with crystalloid and PRBCs, a dilutional coagulopathy develops that is often exacerbated by hypothermia, acidosis, and liver injury as well as concomitant disseminated intravascular coagulation. Contemporary practice is to transfuse plasma and platelets concurrently with PRBCs to avert the development of dilutional coagulopathy. During resuscitation, patients must be monitored for electrolyte disturbances such as hypocalcemia (because the citrate in the anticoagulant used for all blood components binds free calcium, which lowers the serum calcium concentration), hyperkalemia or hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis (from citrate metabolism).

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia presents a unique transfusion challenge. Warm reactive autoantibodies are usually polyclonal IgG antibodies directed against erythrocytes (the patient's own, reagent, and donor erythrocytes). The clinical significance of warm autoantibodies derives from their hemolytic potential and their interference with routine pretransfusion compatibility testing, specifically the detection of alloantibodies and the provision of crossmatch-compatible blood. The urgency of the transfusion, particularly the presence of acute cardiopulmonary or central nervous system symptoms, must be considered along with the risk for hidden alloantibodies, which are rare in patients without previous pregnancy or transfusion. Transfused units should be matched for ABO and Rh. Care of these patients should be closely coordinated between the hospitalist, hematologist, and blood bank specialist.

Therapeutic Apheresis

Apheresis procedures use an automated blood cell separator to collect whole blood, separate it into the plasma and cellular components, remove the component contributing to disease, and return the other blood components to the patient combined with replacement fluids. Plasmapheresis for patients suspected of having Guillain-Barré syndrome is a classic example. Crystalloid and colloid fluids are used for replacement, and plasma components are typically avoided. Therapy for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is more appropriately characterized as plasma exchange because fresh frozen plasma is provided as the replacement fluid. The same cell separators can be used to perform plateletpheresis, erythrocyte exchange transfusion, and other procedures in patients with specific indications (Table 26).