MKSAP Bleeding Disorders

- related: Hemeonc

- tags: #hemeonc

Normal Hemostasis

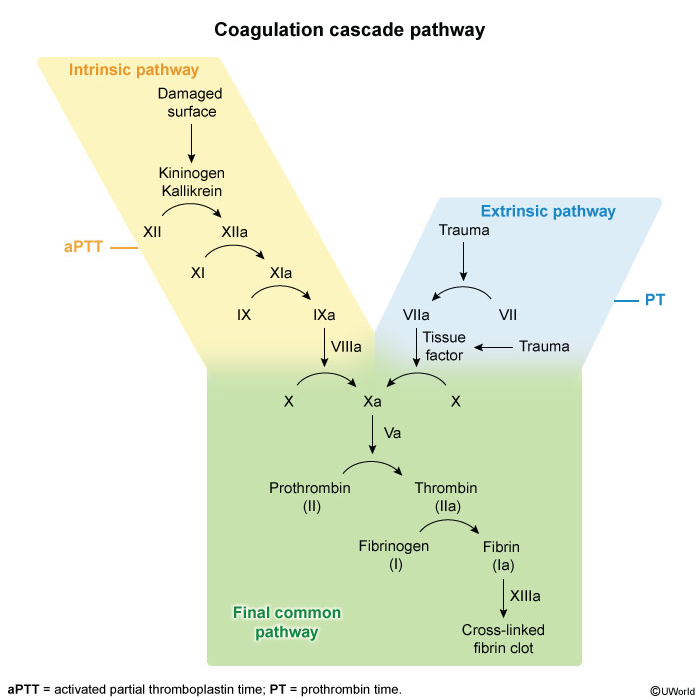

Hemostasis is the process by which bleeding is controlled through a complex network of prothrombotic and fibrinolytic activity. Clot generation occurs on phospholipid membranes through the activation of procoagulant factors (Figure 17). Traditionally, the process was described as a waterfall coagulation cascade (Figure 18), which is still used to understand screening tests and the factors that influence them.

Primary hemostasis describes the interaction between platelets, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and the vessel wall (see Platelet Disorders for platelet activation and vWF activity). Secondary hemostasis refers to the activation of coagulation factors that eventually lead to fibrin clot formation. Clots are then degraded through fibrinolysis.

Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Bleeding Disorders

Patients with bleeding disorders present with symptoms of easy bruising, bleeding gums, menorrhagia, gastrointestinal bleeding, or postoperative bleeding. The clinical history provides guidance regarding how to proceed in the evaluation, with attention paid to history of tooth extraction, menstrual bleeding, minor and major surgical procedures, and family history of bleeding. Medication use and exposure to alcohol or recreational drugs must be documented. The physical examination focuses on finding evidence of petechiae, ecchymoses, deep tissue hematomas, or joint effusions.

Laboratory tests used to measure hemostasis are the prothrombin time (PT) and the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). The PT, expressed as the INR, is more sensitive to the effects of the vitamin K–dependent factors (II, VII, and X), whereas the aPTT is a more sensitive measurement of factors VIII, IX, XI, and XII. The thrombin time measures fibrinogen convergence to fibrin clot, and the Platelet Function Analyzer-100 (PFA-100®) measures platelet function. Specialized tests include mixing studies to evaluate inhibitors, specific factor level assays, and tests for fibrin degradation products and D-dimers.

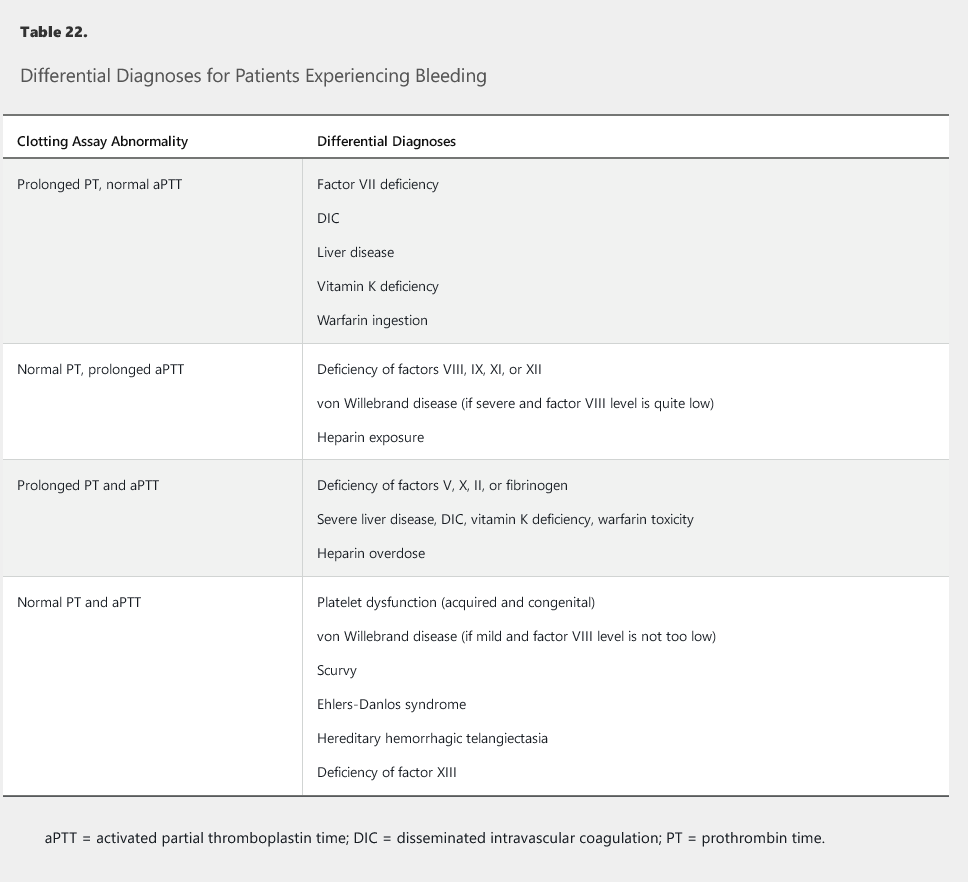

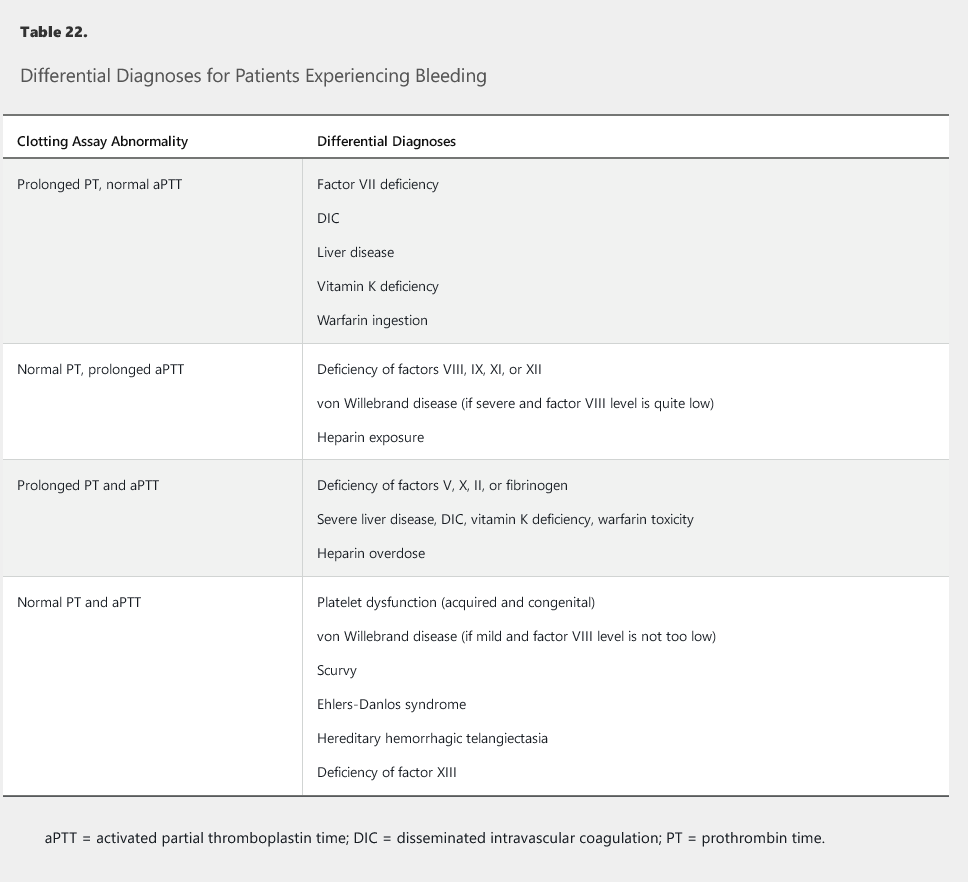

Differential diagnoses for patients experiencing bleeding and who have abnormal findings on specific clotting assays are outlined in Table 22.

Congenital Bleeding Disorders

Hemophilia A and B and Other Factor Deficiencies

Hemophilia A and B (deficiency of factors VIII and IX, respectively) are X-linked hereditary bleeding disorders primarily found in male patients. Daughters of men with hemophilia are obligate carriers. Hemophilia A is more common than hemophilia B, but both are rare. They present in a similar fashion, with spontaneous hemarthrosis or bleeding into deep muscles or with excessive or delayed bleeding after trauma. Small cuts do not usually bleed excessively, but patients experience mucocutaneous bleeding. The hemophilias are classified as mild, moderate, or severe according to the circulating factor levels (mild, 5%-40%; moderate, 1%-5%; severe, <1%). Patients with mild disease may not present until adulthood.

Diagnosis requires a prolonged aPTT (that corrects in mixing studies) and a normal PT and complete blood count. Assay of individual factors (VIII and IX) confirms the diagnosis. In hemophilia A, vWF must be measured to rule out type 3 von Willebrand disease (see next section).

Arthropathy of the knees, ankles, and elbows occurs as a late sequela in 50% of patients as a result of recurrent hemarthroses. Inhibitors to infused factors (see Management) develop in up to 25% of patients with hemophilia A, and 3% to 5% of patients with hemophilia B.

Managing bleeding in hemophilia A and B requires using virally inactivated factor concentrates (eliminating the historical risk of hepatitis and HIV). Patients with mild hemophilia A can be treated with desmopressin, which stimulates the release of preformed factor VIII from endothelial cells. Antifibrinolytic agents (such as ε-aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid) are useful in controlling bleeding from dental procedures.

Factor XI deficiency (also known as hemophilia C) is a rare autosomal hereditary disorder seen predominantly in persons of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. Bleeding symptoms are variable and cannot be predicted by the level of factor XI alone. Asymptomatic patients do not require intervention (for example, before surgery); symptomatic patients require plasma infusions for bleeding episodes and surgical procedures.

Von Willebrand Disease

Von Willebrand disease (vWD), the most common hereditary bleeding disorder, is caused by either deficiency or ineffectiveness of vWF. vWF promotes platelet adhesion and functions as a protective carrier protein for factor VIII, so a mild secondary decrease in factor VIII levels occurs. vWF deficiency leads to mucocutaneous bleeding symptoms that mimic thrombocytopenia.

Hereditary vWD is subclassified into three broad groups (Table 23), with type 1 being the most common. Patients become symptomatic when vWF levels decrease to less than 30%. Clinical features influence vWF levels, including type O blood (decreased levels) and pregnancy or oral contraceptive use (increased levels). Although the aPTT may be prolonged or normal, a prolonged closure time on the PFA-100® would suggest vWD, making this a useful initial evaluation tool. The diagnosis is confirmed by finding a reduction in von Willebrand antigen (quantitative analysis) and reduced vWF ristocetin cofactor activity (a measurement of the functional affect) (see Table 23).

Management of vWD depends on the severity of bleeding, the type of vWD, and the clinical setting. Desmopressin is effective in type 1 vWD, releasing preformed vWF and factor VIII from endothelial cells. It can be given intravenously before a surgical procedure or intranasally as needed in the outpatient setting. Patients with rare type 2B vWD should not receive desmopressin because it induces platelet aggregation, which can cause secondary thrombocytopenia in these patients. Desmopressin is ineffective in patients with type 3 vWD. vWF concentrates are the preferred treatment for these two subgroups; cryoprecipitate is no longer used because virally inactivated vWF concentrates are safer and more effective. Antifibrinolytic therapy (ε-aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid) is useful after surgical procedures to protect against delayed bleeding and can be used to treat menorrhagia.

Acquired Bleeding Disorders

Coagulopathy of Liver Disease

Bleeding in patients with liver disease results from one of many interrelated hemostatic aberrations. The liver is the site of production for procoagulant and fibrinolytic factors. Liver disease is associated with bleeding and thrombosis, but only bleeding manifestations will be discussed here.

Liver disease can result in factor deficiency, hyperfibrinolysis, and mild to moderate thrombocytopenia, leading to PT prolongation, INR elevation, and aPTT prolongation. Distinguishing between liver disease and disseminated intravascular coagulation may be challenging. Measuring factor VIII levels provides a theoretical means of separating the two disorders. Factor VIII is not produced in the hepatocytes, is often elevated in liver disease, but is usually consumed in intravascular coagulation. Additionally, a stable platelet count with mildly elevated D-dimer level suggests liver disease, especially if clinical findings of portal hypertension, consistent with that diagnosis, are present. Patients often have components of both liver disease and disseminated intravascular coagulation, and management rarely differs based on distinguishing the two disorders.

Asymptomatic patients do not require treatment, but vitamin K supplementation should be considered if the INR is elevated. Patients experiencing bleeding may require blood product replacement, with cryoprecipitate to increase fibrinogen levels to greater than 100 mg/dL (1 g/L) and platelet transfusions to maintain a platelet count greater than 50,000/µL (50 × 109/L). Correction of modest thrombocytopenia (platelet count >75,000/µL [75 × 109/L]) or coagulopathy (INR <2) is unnecessary in patients with liver disease who are undergoing paracentesis, thoracentesis, or routine upper endoscopy. Thrombopoietin agonists such as avatrombopag are alternatives to platelet transfusion but require approximately 10 days to raise the platelet count to reduce the risk of procedure-related bleeding. Fresh frozen plasma has be given for INRs greater than 2, but the short half-life of plasma components and risk of volume overload limit the effectiveness of plasma administration. Prothrombin complex concentrates are costly and associated with thrombotic complications; they should not be routinely used in managing the coagulopathy of liver disease. Accelerated fibrinolysis also contributes to bleeding, but no laboratory tests reliably measure this condition. Viscoelastic testing may be useful, although the predictive value in documenting accelerated fibrinolysis is debated and the test is not widely available. Antifibrinolytic agents are useful in treating hyperfibrinolysis and should be considered when persistent oozing from mucous membranes or delayed bleeding from procedure sites occurs in the absence of or despite correction of overt coagulopathy.

Vitamin K Deficiency

Although vitamin K is found in green vegetables, a significant proportion of the daily requirement comes from gut microflora (which may be destroyed by antibiotics); absorption requires biliary and pancreatic function because vitamin K is fat soluble. It acts as a cofactor for carboxylation and activation of certain coagulation factors (see Table 22), as well as for the endogenous anticoagulants, protein C, and protein S. Patients who cannot take anything by mouth, who have poor oral intake while taking long courses of antibiotics, and who have fat malabsorption are especially at risk for vitamin K deficiency. Vitamin K supplements safely and effectively correct the deficiency, so this diagnosis should always be considered when evaluating a patient with a prolonged PT. The response to supplementation occurs within hours because vitamin K acts by converting precursor proteins synthesized in the liver into active factors. Vitamin K can be administered orally for patients who are able to eat. Critically ill patients or those unable to take anything by mouth should receive vitamin K by slow intravenous infusion. Subcutaneous vitamin K is not reliably absorbed and is unlikely to be safer than intravenous vitamin K.

Acquired von Willebrand Disease

Acquired vWD occurs in conditions of high circulatory shear stress (valvular heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, circulatory assist devices, and extracorporeal membrane-oxygenation systems) caused by excessive degradation of high-molecular-weight von Willebrand multimers by the proteolytic enzyme ADAMTS13. Affected patients develop bleeding conditions similar to those in hereditary vWD. The prevalence of this disorder is likely to increase as more patients with severe cardiomyopathy are managed with left ventricular assist devices. These patients are routinely managed with warfarin and antiplatelet agents and have a significant incidence of gastrointestinal or other bleeding problems. Desmopressin and vWF concentrates have been used in management.

Acquired Hemophilia

Acquired hemophilia results from an autoantibody directed against factor VIII. Patients present with bleeding symptoms that mimic hereditary hemophilia A. Approximately half of all cases are associated with pregnancy and the postpartum state, malignancy, and other autoimmune disorders, as well as with medications.

Laboratory evaluation shows a normal platelet count and PT with a prolonged aPTT. Mixing studies do not correct the aPTT. Factor analysis shows a low factor VIII level; an inhibitor can be quantified with the Bethesda assay. One Bethesda unit is defined as the reciprocal of the dilution of patient plasma that results in 50% inactivation.

Factor VIII concentrates do not correct the problem. Management of acute bleeding requires plasma derivatives or recombinant coagulation factors that bypass the inhibited factor, such as activated prothrombin complex concentrates or recombinant activated factor VII. Recombinant porcine factor VIII provides more effective hemostasis, but it may be limited in availability. Immunosuppression, using corticosteroids, usually combined with rituximab or cyclophosphamide, is required to eliminate the autoantibody and prevent continued production of inhibitors.

Acquired hemophilia A is just one example of an autoimmune factor deficiency. Acquired inhibitors can occur against any factor and should be considered whenever a patient presents with a new bleeding diathesis and an unexpectedly low factor level.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation results from the simultaneous stimulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis. It is associated with severe sepsis, usually with septic shock; with disseminated malignancy, most classically with mucin-secreting pancreatic adenocarcinoma; and in pregnancy with various severe complications, including sepsis, placental abruption, and eclampsia. Patients with life-threatening illnesses characterized by systemic immune response syndrome with hypotension and multiorgan dysfunction are also at risk. The initial pathogenesis involves widespread endothelial injury and circulating procoagulants that lead to disseminated microvascular thrombi, with consumption of platelets and clotting factors, and erythrocyte shearing injury leading to hemolysis. Fibrinolysis is accelerated, resulting in dissolution of the microvascular thrombus, usually before thrombotic complications are noted. These factors leave the patient vulnerable to bleeding from thrombocytopenia, clotting factor depletion, and fibrinolysis. Classic laboratory findings include thrombocytopenia, prolonged aPTT and PT, elevated INR, hypofibrinogenemia, and elevated D-dimer levels, although laboratory features are unpredictable from patient to patient. Management is directed primarily at the inciting cause of disseminated intravascular coagulation and supported with platelet transfusions, cryoprecipitate, and fresh frozen plasma as needed.