Lymphoid Malignancies

- related: Hemeonc

- tags: #hemeonc

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2018 83,180 new cases of lymphoma will be diagnosed in the United States. The lifetime risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma is 2.1%, whereas the lifetime risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma is considerably less. Although incidence has only slightly declined recently, death rates have decreased significantly owing to improvements in treatment. The incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma rises with increased age, whereas the incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma shows a bimodal age distribution, with an early peak in the second and third decades of life, then a decline, followed by a sustained increase with older age.

Although most of these cases seem sporadic, familial clustering can be seen, with an increased relative risk in first-degree relatives. Patients with both congenital and acquired immunosuppression (such as HIV infection, organ transplantation, or an inherited immunodeficiency) are at greater risk.

Various viral infections are also associated with increased risk. Epstein-Barr virus is associated with Burkitt lymphoma, seen in African pediatric patients, as well as some cases of Hodgkin lymphoma. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is associated with T-cell leukemias and lymphomas, endemic in Japan, West Africa, Central America, the southeastern United States, and the Caribbean. Hepatitis C virus is associated with an increased risk of lymphoma, particularly splenic marginal zone lymphoma. HIV infection is associated with an increased risk of principally B-cell lymphomas, typically with aggressive histology, more advanced stage, more B symptoms, and a higher risk of extranodal and central nervous system involvement. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) is associated not only with Kaposi sarcoma but also with primary effusion lymphoma.

Patients with autoimmune rheumatic disorders, such as Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis, have an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The strongest association is with Sjögren syndrome and extranodal marginal zone lymphomas.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Enlarged lymph nodes are the most common sign of lymphoma. There are many causes of lymphadenopathy, and in most patients, it is of benign origin (infectious or inflammatory). Palpable small and modest-sized cervical and inguinal lymph nodes may be noted in otherwise healthy adults and need not be evaluated further. This finding in young adults and of brief (less than 3 to 4 weeks) duration is likely to be benign. CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis can assess palpable lymph nodes not amenable to physical examination but generally should not be done in asymptomatic patients. When the size, distribution, or persistence of enlarged lymph nodes or systemic symptoms raises concern for lymphoma, a diagnosis is generally established based on lymph node biopsy. An excisional biopsy is often preferable to a core needle biopsy as it may better determine nodal architecture. Fine-needle aspiration cytology is generally inadequate to make a specific diagnosis, but it may show features suspicious for lymphoma, requiring a more definitive excisional biopsy or, conversely, may reveal findings consistent with inflammation that make lymphoma less likely. Flow cytometry on cytology can demonstrate B-cell or T-cell markers, as well as features consistent with monoclonality.

Although most patients with lymphoma present with lymph node involvement, presentation in extranodal sites is not uncommon.

Classifications, Staging, and Prognosis of Malignant Lymphoma

Malignant lymphoma represents a spectrum of disorders. Diagnosis and classification are established not just on standard histopathologic staining looking at cell type and nodal architecture but also on flow cytometry, various immunohistochemical stains, and cytogenetic and molecular genetic features. The classification systems are complex and have continued to evolve during the past decades. The most commonly recognized system is the World Health Organization update on the Revised European-American Lymphoma classification. Experienced hematopathologists are essential to obtaining proper classification. However, there can be significant discordance among experts and some overlap among tumor types.

Staging the anatomical extent of spread can be simplified through the Ann Arbor staging criteria (Figure 21).

Lymphomas are staged I to IV based on the number of sites of disease and the presence of extranodal involvement. Staging involves physical examination, CT scans, and PET scans in most patients. However, PET scans tend not to be sensitive for some very indolent lymphomas (such as small lymphocytic lymphoma and marginal zone lymphomas). Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy have typically been part of staging for many lymphomas, but the use of PET scans may obviate the need for bone marrow biopsies in many patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and large cell lymphoma as marrow involvement is rarely found if it is not suggested by PET.

Lymphoma stages are also designated A or B; A indicates no systemic symptoms are present, and B indicates the presence of one or more of the following: fever, drenching night sweats, or unexplained weight loss.

The prognosis of the lymphoma varies greatly depending on the subtype, stage, and comorbidities. Immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and molecular genetic classifications also commonly inform the prognosis. Prognostic indices have been reported and validated for most common types, including the International Prognostic Index for large cell lymphoma, the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index, and the Mantle cell lymphoma Prognostic Index.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas

Approximately 85% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas are B-cell derived and express surface immunoglobulin and B-cell markers, whereas 15% are T-cell derived.

Indolent B-Cell Lymphomas

The indolent lymphomas may be present for many years without symptoms and typically have a favorable response to various sequential therapies when needed, but all have a tendency for continued relapse.

Follicular Lymphoma

Follicular lymphomas demonstrate lymph node architecture with a follicular morphology. They arise from the germinal center B cells of the lymph node and are characterized by the presence of a t(14;18) translocation that causes an overexpression of the BCL2 oncogene. Follicular lymphomas are classified based on their dominant cell type: predominantly smaller cells (grade 1), a mixture of smaller and larger cells (grade 2), and predominantly large cells (grade 3). Grades 1 and 2 are commonly combined as the distinction between them is somewhat subjective. Grade 3 follicular lymphoma can be divided into 3A and 3B, with the latter composed of sheets of more uniform poorly differentiated cells. Grade 3A follicular lymphoma is more akin in behavior and treatment to grades 1 and 2, whereas 3B is treated more like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, although this is somewhat controversial.

Follicular lymphoma is the most common indolent B-cell lymphoma and accounts for approximately 30% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Many patients are not symptomatic at diagnosis and in some cases do not require therapy for many years. There is no clear evidence that early treatment leads to improved outcomes, so asymptomatic patients without bulky disease are usually observed. Some patients may undergo spontaneous, although generally transient, regression of disease.

Most patients with follicular lymphoma will present with stage III or IV disease. Single-agent rituximab is associated with high response rates and durable remissions. Combining rituximab with chemotherapy (such as the alkylating agent bendamustine) leads to remission in more than 90% of patients. The use of maintenance rituximab after induction of an initial remission is associated with prolonged duration of remission or relapse-free survival, but no clear improvement in overall survival. Patients with relapsing or refractory cases can be treated with various other approaches, including alternate chemotherapy regimens (such as rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [R-CHOP]), the anti-CD20 antibody obinutuzumab, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor idelalisib, radioimmunotherapy with ibritumomab tiuxetan, as well as autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

A minority of patients present with localized disease and can be approached with radiation therapy with curative intent rather than with systemic therapy. Whether systemic therapy, such as rituximab, with or without chemotherapy should be used in addition to or as an alternative to radiotherapy in patients with localized follicular (and other low-grade) lymphomas is controversial.

Histologic transformation, most typically to a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, occurs in approximately 30% of patients with follicular lymphomas and is associated with an aggressive course and poor prognosis. Transformation may be suggested by a change in the clinical pattern of disease with new systemic symptoms or rapid progression of a localized area of disease, a rise in serum lactate dehydrogenase, or markedly higher areas of standardized uptake values on PET scans. A new biopsy is required to establish that transformation has occurred.

Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is an extranodal marginal zone lymphoma. Gastric MALT lymphoma may be the best known, particularly given its common association with Helicobacter pylori infection. However, MALT lymphomas can arise in other sites such as the gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, orbits, skin, and lung and generally demonstrate indolent behavior and a low propensity for transformation. Repetitive immune stimulation, from underlying chronic infection or an autoimmune process, is likely to play a role in the pathogenesis of this tumor.

H. pylori–associated gastric MALT lymphoma should be treated with antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors initially. Other localized MALT lymphomas may be treated with radiation, to which they are quite sensitive. When systemic therapy is required, rituximab alone or in combination with chemotherapy is associated with high response rates.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is generally easy to diagnose because it manifests as an increase in absolute lymphocytes on complete blood count. The lymphocytes are predominantly small and mature appearing, although they may be fragile and form “smudge cells” on the peripheral smear. Flow cytometry using peripheral blood is essential in establishing the diagnosis and will reveal B-cell antigens (CD19, 20, and 23), coexpression of CD5 (normally a T-cell marker), and low levels of a monoclonal surface immunoglobulin. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are no longer necessary to diagnose and stage most patients with CLL.

Although less common, other lymphomas may present similarly to CLL in peripheral blood smears and must be distinguished by morphology, flow cytometry, and genetic studies. These other disorders include hairy cell leukemia, marginal and mantle zone lymphomas, T-cell lymphoma, and prolymphocytic leukemia.

CLL and small lymphocytic lymphoma represent the same disease, with the designation as leukemia or lymphoma based on the dominant clinical manifestation in either peripheral blood and marrow or nodal involvement, respectively. Both CLL and small lymphocytic lymphoma are treated the same. CLL is now grouped more with the lymphomas than with the leukemias in treatment centers.

CLL is typically an indolent disease, and many patients require no therapy for many years and sometimes decades. Prognosis can relate to clinical staging (Rai and Binet staging systems are based on the extent of cytopenias, organomegaly, and degree of nodal involvement) but also on cytogenetic and molecular genetic characteristics. The specific nature of the mutation can help indicate the prognosis.

The past decade has seen a rapid advance in the number and efficacy of active agents for CLL. Although these therapies are not curative, most patients can now achieve durable remissions once treatment is required. Treatment options available include alkylating agents (chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, bendamustine), purine nucleoside analogues (fludarabine, cladribine, pentostatin), monoclonal antibodies (rituximab, alemtuzumab, ofatumumab, obinutuzumab), and the phosphoinositide-3 kinase inhibitor idelalisib. There has been an increase in use of the Bruton kinase inhibitor ibrutinib, which is now approved for first-line therapy and active in a broad spectrum of patients, including those with 17p deletion. Venetoclax, a BCL2 inhibitor, is active in refractory cases, induces brisk apoptosis, and occasionally induces tumor lysis syndrome. Lenalidomide, an immune modulator approved for myeloma and myelodysplasia, is also active. Allogeneic HSCT is rarely performed in CLL but has been used in refractory cases in appropriate patients. Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has also been shown to be active in refractory cases. Older chemoimmunotherapy regimens, although quite active, may increasingly give way to targeted therapies.

Patients with CLL are prone to infection, in part related to commonly associated hypogammaglobulinemia. In patients with repeated infections and hypogammaglobulinemia, regular treatment with intravenous gamma globulin reduces infectious events. The infection risk increases in more advanced disease, a result of both impaired T-cell-mediated and B-cell-mediated immune response along with treatment-induced immunosuppression. Patients with CLL and small lymphocytic lymphoma may also develop autoimmune cytopenias such as immune thrombocytopenic purpura and autoimmune hemolytic anemias. Transformation to a large cell lymphoma (known as Richter transformation) occurs in about 5% of patients with CLL and small lymphocytic lymphoma and is generally associated with a poor prognosis and refractory disease.

Hairy Cell Leukemia

Like CLL, hairy cell leukemia is a low-grade B-cell disorder but with characteristic clinical, pathologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic changes. Patients typically present with cytopenias and splenomegaly; lymphadenopathy is typically absent. Circulating “hairy cells,” characterized by cytoplasmic projections, are often identified in the peripheral blood smear (Figure 22); when seen on bone marrow biopsy, these cells have a lacunar appearance. Classically, the bone marrow aspirate is a dry tap due to some degree of marrow fibrosis. Flow cytometry shows hairy cells positive for characteristic surface markers. In addition, the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation has been associated with hairy cell leukemia in most patients and represents not only a diagnostic marker but also a therapeutic target.

As with CLL and other low-grade lymphomas, some patients with hairy cell leukemia do not require immediate treatment if not symptomatic. However, the front-line therapy remains purine nucleoside agents, typically pentostatin or cladribine. These agents are highly active, and almost all patients respond, many with durable responses, with only one course of treatment. Relapses can be treated with the alternate purine nucleoside agent. Rituximab is also active in relapse. The selective BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib has also shown activity in relapsed patients.

Hairy cell leukemia variant is a distinct entity that typically presents with a high circulating leukocyte count, as opposed to the leukopenia seen in the classic form. These patients respond less well to cladribine and have shorter durations of response.

Aggressive B-Cell Lymphomas

The more aggressive lymphomas, such as diffuse large B-cell and Burkitt lymphoma, are more likely to present with systemic symptoms or signs of rapid tumor progression. Diagnosis should be promptly pursued because these patients have a greater potential for cure with therapy.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma represents approximately 30% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Although diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can be subdivided based on gene expression profiling (activated B-cell versus germinal center type), and although this subtyping may be associated with prognostic differences, there is no clear indication yet that the initial treatment approach should be altered based on the subtype. These patients often present with symptomatic enlarging lymphadenopathy in the neck or abdomen. Approximately 40% may have symptoms or signs of extranodal disease, and one third have systemic symptoms. Biopsy specimens show diffuse effacement of normal nodal architecture by large, atypical lymphoid cells with prominent nucleoli and basophilic cytoplasm. Flow cytometry reveals B-cell antigens, and most patients have monoclonal surface immunoglobulin. The B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) gene shows rearrangement or other mutations that lead to overexpression in most patients.

Sixty percent of patients have advanced (stage III or IV) disease at diagnosis, and standard therapy is R-CHOP. Consolidative radiation therapy may be given to sites of bulky disease. Residual masses, which are often benign, may remain after treatment. PET may help determine if these represent active disease or just scarring.

Patients with poor prognostic features, such as elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level, extensive tumor burden, and poor performance status, may receive more aggressive initial therapy. Those patients who present with localized disease can be treated with a shorter course of chemotherapy with consolidative radiation therapy. In addition to further standard chemotherapy, autologous HSCT and anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy may be used as salvage therapy in patients who relapse.

Primary mediastinal large cell lymphoma is a distinct clinical, morphologic, and genetic lymphoma, often presenting in younger patients. It putatively arises from thymic B cells. It has a female predilection, a tendency to present with bulky but localized disease, and a relatively high cure rate. It may have significant overlap histologically and genetically with nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma, and some cases may be difficult to classify as one or the other; these are called mediastinal gray-zone lymphomas.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphomas represent approximately 3% to 6% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Median age at diagnosis is 68 years, and there is a 3-to-1 male predominance. It is defined and presumably initiated by a t(11;14) translocation, which leads to constitutive overexpression of cyclin D1, a cell-cycle gene regulator. Patients can present with nodal or extranodal disease, and the disease is usually widely disseminated at diagnosis. Gastrointestinal involvement with several polyps (lymphomatoid polyposis) is well described, as is involvement of the peripheral blood and bone marrow.

Although mantle cell lymphoma is responsive to various conventional chemotherapy regimens and newer agents, it is associated with a predilection for continued relapse. There is no clear consensus on the optimal therapeutic approach, with treatments spanning a spectrum of least aggressive (lenalidomide or bendamustine plus rituximab) to more aggressive (R-CHOP with or without HSCT). A subset of patients with indolent disease may not require therapy for many years.

Burkitt Lymphoma

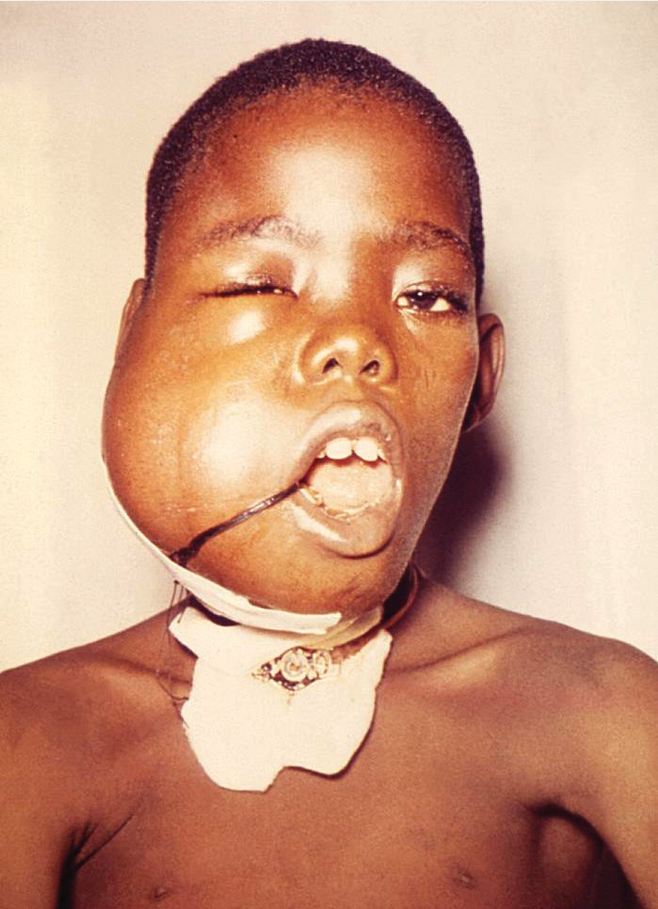

A relatively rare lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, is remarkable for its extremely rapid growth. The endemic form occurs primarily in Africa, is a common cause of childhood cancer, and is associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Patients may present with a large jaw mass (Figure 23). The sporadic form is more typically seen in the United States, occurs at a somewhat later age, and is more likely to present with abdominal or pelvic involvement. A third variety of Burkitt lymphoma is the immunodeficiency-associated form and occurs in HIV-infected patients. MYC gene activation is characteristic of this lymphoma. The serum lactate dehydrogenase level is typically high.

Early signs of the tumor lysis syndrome are often present in patients with Burkitt lymphoma even before treatment is initiated and should be anticipated because the tumor is quite chemosensitive. Various aggressive multiagent chemotherapy regimens with rituximab have been associated with high cure rates. These regimens are more intensive than standard lymphoma therapy and are associated with some risk of treatment-related mortality (for a more complete discussion, see Oncologic Emergencies and Urgencies). Treatment of occult central nervous system involvement is included in initial treatment regimens because of the risk for leptomeningeal involvement.

T-Cell Lymphomas

T-cell lymphomas represent approximately 10% to 15% of lymphomas in Western countries but are more common in Asia. They include various subtypes and are a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by distinct presentations and morphology. Diagnosis can be made on routine pathology and supplemented by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Monoclonality can be confirmed by findings of clonal rearrangements of the T-cell receptor genes detected by polymerase chain reaction. In general, T-cell lymphomas are more refractory to therapy than B-cell lymphomas. Although various new agents are available for treatment, studies are small and many responses are transient.

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome are the two major subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The skin findings in mycosis fungoides are quite heterogeneous, ranging from nonspecific macular-papular eruptions or plaques, to more defined skin tumors with ulceration, to diffuse erythroderma. There is often a preceding prodromal illness, or “premycotic” period, with milder skin disease that waxes and wanes or that may progress for months or even years without a definitive diagnosis; skin biopsies done during that interval are nonspecific. Pruritus is common and can be debilitating. Ultimately, as skin involvement becomes more extensive, the disease progresses to involve extracutaneous sites, including lymph nodes and organs, such as the lung, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Infections are more common as a function of underlying immunodeficiency and disruption of the protective barrier provided by healthy skin. The Sézary syndrome is a more aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in which diffuse erythroderma characterizes the skin involvement and malignant T cells circulate in the blood.

The staging of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is dependent on the extent of skin disease and involvement of lymph nodes and extranodal sites. Early stages of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are confined to the skin and managed with topical therapy, such as glucocorticoids, retinoids, or ultraviolet light therapy, that may be combined with interferon. Survival is greater than 10 years. More advanced disease is associated with a survival of less than 4 years and requires more aggressive skin treatment with electron beam radiation along with systemic chemotherapy. Patients with Sézary syndrome require systemic chemotherapy. Extracorporeal photopheresis uses psoralens, compounds that enter cells and sensitize them to injury after activation with ultraviolet light; this technique is also used in Sézary syndrome.

Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, is the most commonly diagnosed subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. It typically presents in older adults at an advanced stage, has a male predominance, and has a generally poor clinical outcome compared to B-cell lymphomas.

Various combination chemotherapy regimens have been used. The addition of etoposide to standard combination chemotherapy may provide some benefit as part of initial therapy. The use of chemotherapy designed for acute lymphoblastic leukemia or management with HSCT, both autologous and allogeneic, may benefit some patients, although there is controversy as to when and in whom these are best used. As with other T-cell lymphomas, newer chemotherapy agents such as pralatrexate and romidepsin yield responses in some patients with relapsed disease.

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma can present with nodal as well as extranodal disease, including skin, bone marrow, and bone. Patients commonly have B symptoms. Tumor cells are typically CD30 positive. An important prognostic and potentially therapeutic distinction is the presence or absence of a t(2;5) or variant ALK gene translocation and protein expression.

ALK-positive patients are younger (mean age at diagnosis is approximately 35 years) and have a much more favorable prognosis with conventional chemotherapy and may also respond to treatment with crizotinib, an oral targeted agent also active in lung cancer with ALK gene translocations.

Angioimmunoblastic T-Cell Lymphoma

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, initially termed angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy, was thought to be a disease of impaired immune regulation rather than a true malignancy; however, patients with this disease are now recognized to have clonal rearrangement of T-cell receptors consistent with a T-cell neoplasm. Patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma often present with systemic B symptoms, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and a skin rash. They commonly show polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level. Autoimmune manifestations (such as a Coombs-positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia) may be present. Although the lymphoma in some patients is responsive to glucocorticoids and conventional chemotherapy, it typically has a moderately aggressive clinical course and median survival of less than 2 years.

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

Lymphoblastic lymphoma is an aggressive lymphoma that can be of T- or B-cell origin. It is akin to and treated with protocols for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Presentation with a mediastinal mass, blood or bone marrow, and central nervous system involvement is typical.

Hodgkin Lymphoma

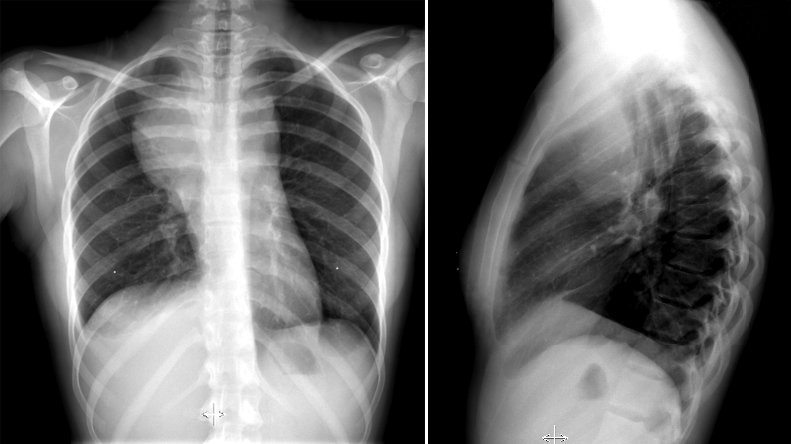

Hodgkin lymphoma represents approximately 10% of lymphomas and is curable in most, but not all, patients. It has a bimodal incidence, although it most commonly presents in young adults. Presentation with mediastinal, cervical, and supraclavicular involvement is particularly common for the nodular sclerosing subtype (Figure 24). Patients may also present with B symptoms, although that is more commonly seen in elderly patients with more advanced disease. Pruritus may also be a presenting symptom.

Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common lymphoma to involve the mediastinum, shown in this chest radiograph (left) as a mass that originates from the mediastinum, given the convex angles resulting from the mass impinging on the pleura. The lateral film (right) localizes the mass to the anterior mediastinum. Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common cause of anterior mediastinal masses in patients aged 20 to 30 years.

Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common lymphoma to involve the mediastinum, shown in this chest radiograph (left) as a mass that originates from the mediastinum, given the convex angles resulting from the mass impinging on the pleura. The lateral film (right) localizes the mass to the anterior mediastinum. Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common cause of anterior mediastinal masses in patients aged 20 to 30 years.

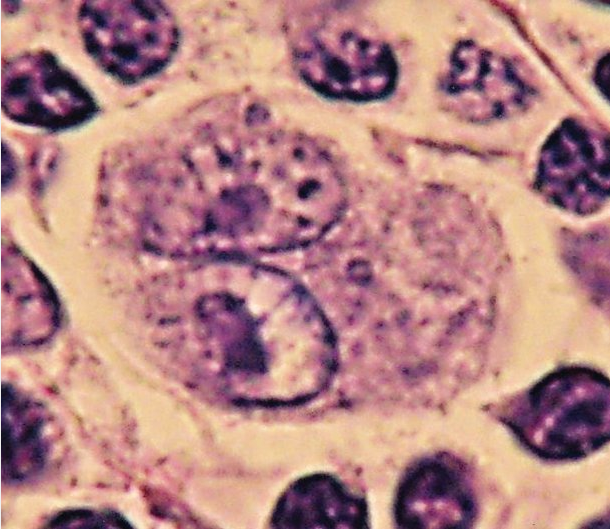

The diagnosis is established with a lymph node biopsy specimen showing Reed-Sternberg cells (Figure 25), malignant cells that originate from germinal center B cells and are seen in an inflammatory infiltrate. The number of Reed-Sternberg cells and variability in the composition of the infiltrate lead to pathologic subtypes, including nodular sclerosis, mixed cellularity, lymphocyte predominant, and lymphocyte depleted. Patients are staged by physical examination and PET-CT scan. Staging laparotomies, including diagnostic splenectomy, are no longer done. Routine bone marrow biopsy, in the absence of unexplained blood abnormalities, is not indicated.

Reed–Sternberg cells are large and either are multinucleated or have a bilobed nucleus (“owls eye” appearance) with prominent eosinophilic inclusion-like nucleoli. They can be seen with light microscopy in biopsies from individuals with Hodgkin lymphoma. They are usually derived from B lymphocytes. When seen against a sea of B cells, they give the tissue a “starry sky” or “moth-eaten” appearance. The absence of Reed–Sternberg cells has very high negative predictive value for Hodgkin disease.

Reed–Sternberg cells are large and either are multinucleated or have a bilobed nucleus (“owls eye” appearance) with prominent eosinophilic inclusion-like nucleoli. They can be seen with light microscopy in biopsies from individuals with Hodgkin lymphoma. They are usually derived from B lymphocytes. When seen against a sea of B cells, they give the tissue a “starry sky” or “moth-eaten” appearance. The absence of Reed–Sternberg cells has very high negative predictive value for Hodgkin disease.

More than 90% of patients present with “classic” Hodgkin lymphoma pathology and, even with early-stage disease, receive chemotherapy because this has been shown to result in higher cure rates. The doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) regimen is most commonly used in the United States. ABVD has replaced alkylating agent–based regimens such as mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone, in part because of higher rates of fertility preservation and a lower risk of secondary acute leukemia. For patients with early-stage, favorable disease, treatment can consist of short-course chemotherapy (as short as two cycles of ABVD) and involved field radiation. Chemotherapy alone (ABVD for four to six cycles) in patients with good response is also an option. For more advanced disease, chemotherapy alone is used. Although the regimen is usually well tolerated, up to 25% of patients may develop bleomycin-induced lung injury during treatment or within 6 months of its conclusion. A portion of those patients will have sustained exertional dyspnea associated with a decline in pulmonary function.

Complete response indicated by PET scan after two to three cycles of chemotherapy is a reliable prognostic indicator. Early repeat PET scan is an appropriate response-adapted strategy in Hodgkin lymphoma and may allow some patients with early-stage disease to forgo radiation therapy and thereby reduce the risks of late radiation side effects.

For patients with relapsed or refractory disease, salvage chemotherapy and autologous or allogeneic HSCT may provide curative options. Brentuximab vedotin (an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody conjugated with a peptide link to monomethyl auristatin E [MMAE]) is active in refractory disease and has also been used for consolidation after autologous HSCT. The programmed death 1 (PD-1) antibodies (pembrolizumab and nivolumab) are highly active in relapsed or refractory disease. The incorporation of these drugs in earlier treatment regimens is being studied.

Nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is distinct clinically and pathologically from classic Hodgkin lymphoma (nodular sclerosis, mixed cellularity, and lymphocyte depleted). It represents approximately 10% of Hodgkin lymphomas and is more likely to present with localized disease but is associated with a high rate of late relapse. Early-stage disease may be treated with radiation therapy alone. Single-agent rituximab or combined with chemotherapy may be used for more advanced or relapsed disease.