Labor in Pregnancy

First Stage

The first stage of labor begins with the onset of regular, painful contractions and ends at complete (10 cm) cervical dilation. The first stage consists of 2 phases:

- Latent phase: From beginning of regular contractions to 6 cm cervical dilation; characterized by slow cervical change.

- Active phase: From 6 cm to 10 cm (complete) cervical dilation; characterized by rapid (>1 cm/2 hr) cervical change. Active phase protraction is defined as cervical dilation ≤1 cm/2 hr.

The most common cause of labor protraction in the active phase is inadequate (hypotonic) uterine contractions. To be adequate, contractions typically have to occur every 2-3 minutes. This patient has had no cervical change over 2 hours and has inadequate contractions (every 4-6 minutes) in the active phase of labor (ie, cervix ≥6 cm). Patients with inadequate contractions require labor augmentation to increase contraction frequency and/or intensity after spontaneous labor has begun. Administration of oxytocin and an amniotomy (artificial rupture of membranes) are first-line treatments for labor protraction. Without adequate contractions, this patient is unlikely to have labor progression (Choice E).

Cesarean delivery is indicated for arrest of labor (ie, no cervical change in the active phase of labor for >4 hours with adequate contractions or >6 hours without adequate contractions). This patient does not yet meet the criteria for arrested labor.

Second Stage Labor

The second stage of labor begins at complete (10 cm) cervical dilation and ends with fetal delivery. The duration of the second stage is affected by parity and use of neuraxial anesthesia. However, the longer the duration of the second stage, the higher the risk for neonatal (eg, sepsis) and maternal (eg, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis) complications. An arrested second stage of labor occurs when there is no fetal descent (ie, no change in fetal station) after nulliparous patients push for >3 hours without an epidural (or >4 hours with an epidural). Second-stage labor arrest is most commonly caused by cephalopelvic disproportion, which is typically the result of fetal malposition (eg, occiput transverse position) or macrosomia. Management of second-stage labor arrest due to cephalopelvic disproportion is with cesarean delivery.

Increasing the oxytocin infusion rate is indicated for inadequate contractions; this patient has adequate contractions, based on a spontaneous progression to complete dilation. Given the adequate maternal effort, the lack of fetal descent (ie, high fetal station) is due to cephalopelvic disproportion and is unlikely to respond to maternal rest or increased oxytocin.

Operative vaginal delivery (eg, vacuum, forceps) is an option for second-stage labor arrest; however, it is contraindicated if cephalopelvic disproportion is suspected. In addition, a prerequisite for operative vaginal delivery is engagement of the fetal head (ie, fetal station >0).

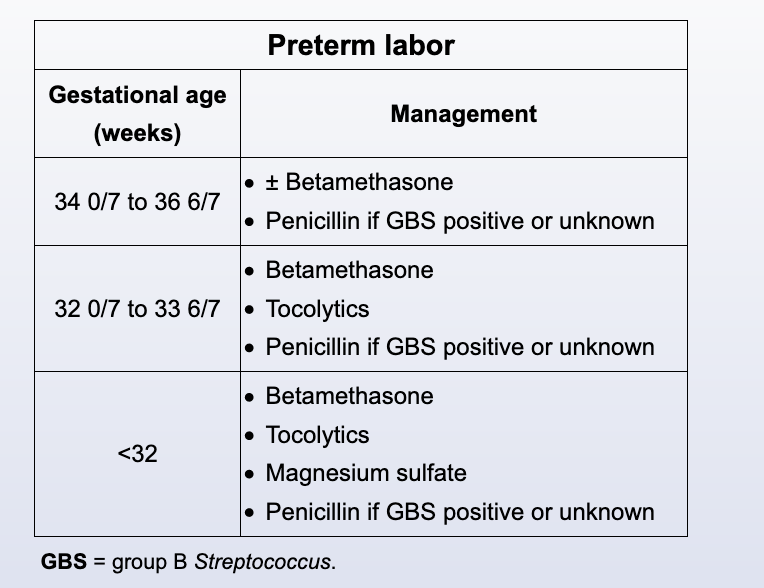

Preterm labor

This patient presents with preterm labor, defined as regular uterine contractions resulting in cervical change (eg, dilation) at <37 weeks gestation. The majority of cases of preterm labor are spontaneous; however, associated risk factors include a history of prior preterm labor, extremes of maternal age, uterine malformations (eg, leiomyoma), and multifetal gestation.

The management of preterm labor involves inhibition of uterine contractions (eg, tocolysis) for prolongation of the pregnancy to maximize fetal protection and development. Variations in management are dependent on gestational age; an earlier gestational age is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, thereby requiring more extensive intervention. Between 32 and 34 weeks gestation, management includes corticosteroids, tocolytics, and penicillin. Intramuscular betamethasone, a corticosteroid, is indicated at <37 weeks gestation as it decreases the risk of respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, and neonatal mortality. Tocolysis between 32 and 34 weeks gestation is with nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker. Penicillin is indicated in patients with either a positive or unknown Group B Streptococcus (GBS) rectovaginal culture to prevent neonatal infection. This patient has a recent negative GBS rectovaginal culture and does not require GBS prophylaxis with penicillin (Choice C).

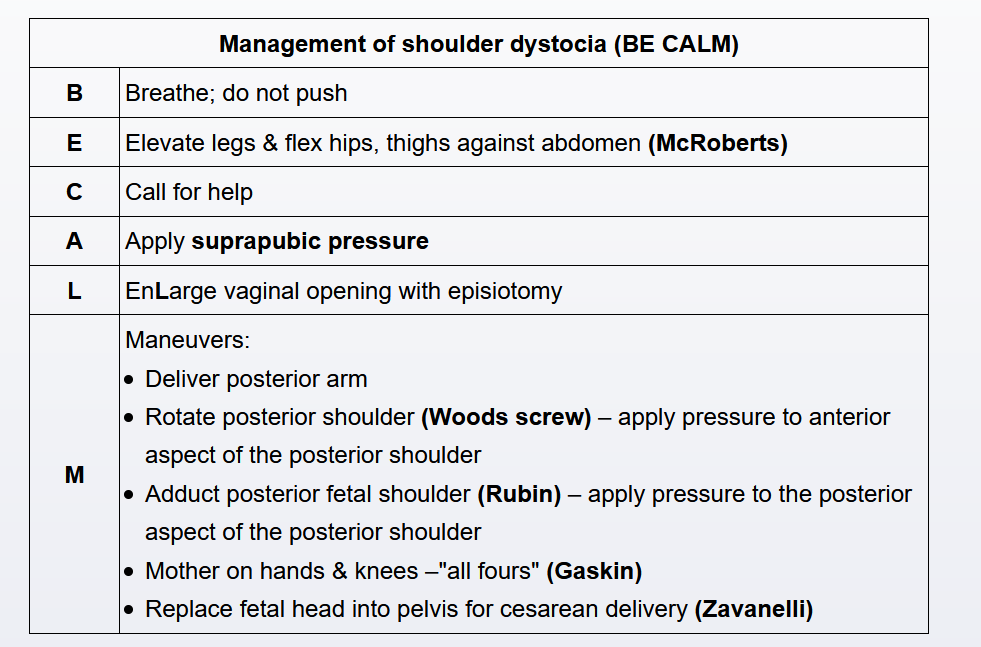

Shoulder Dystocia

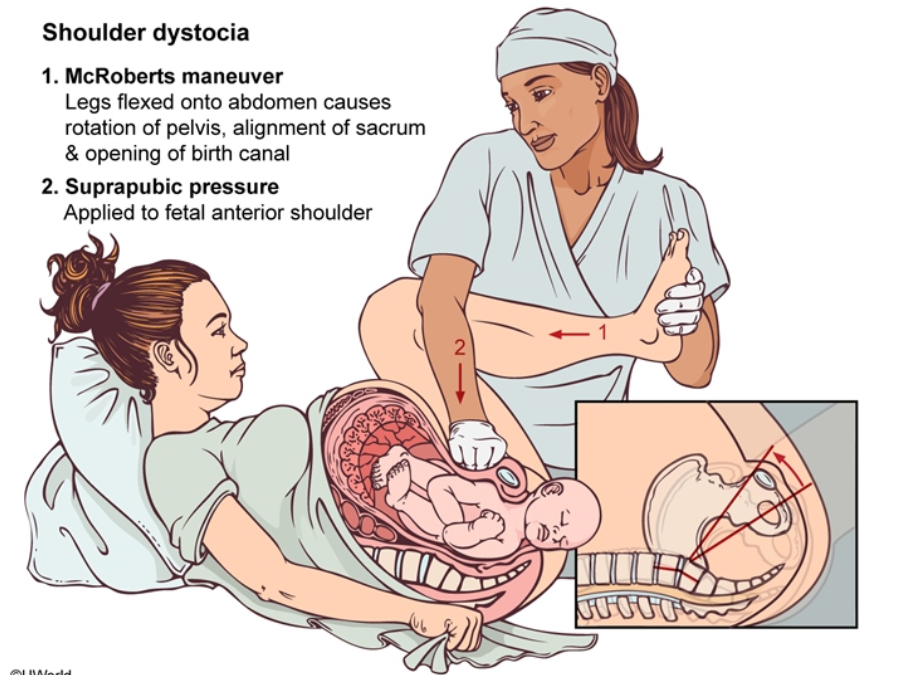

Shoulder dystocia occurs when the anterior fetal shoulder does not deliver with the usual obstetric maneuvers (eg, gentle downward traction). The typical presentation of shoulder dystocia is the retraction of the fetal head into the maternal perineum immediately after delivery ("turtle sign"). Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency associated with fetal risk for brachial plexus injury, clavicular or humeral fracture, hypoxic encephalopathy, and death. Maternal complications of shoulder dystocia include pelvic injury (eg, fourth-degree perineal laceration) and postpartum hemorrhage. Risk factors for a shoulder dystocia include prior shoulder dystocia, diabetes mellitus, maternal obesity, fetal macrosomia, post-term pregnancy, and operative vaginal delivery.

Shoulder dystocia is caused by impaction of the anterior fetal shoulder behind the maternal pubic symphysis. It is managed by the performance of maneuvers that work to disimpact the anterior shoulder. The first maneuver for shoulder dystocia is the McRoberts maneuver, during which the maternal hips are hyperflexed. This maneuver decreases obstruction through the bony pelvis by rotating the pubic symphysis cephalad and flattening the sacral promontory. The combination of McRoberts maneuver and suprapubic pressure frequently relieves the shoulder dystocia with no additional maneuvers required.

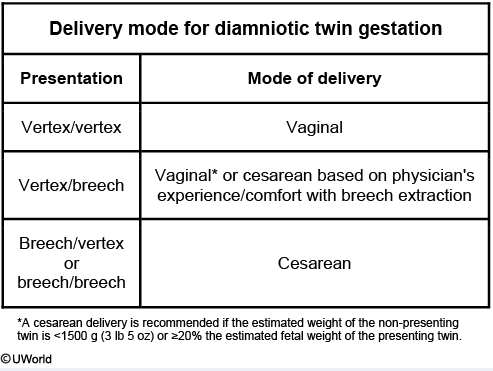

Twin delivery

The delivery of a second twin is associated with an increased risk of umbilical cord prolapse, abruptio placentae, malpresentation, and neonatal death. To minimize these risks, vaginal delivery of twin gestations is offered selectively. In patients with dichorionic/diamniotic twins, mode of delivery is dictated by fetal presentation. When dichorionic/diamniotic twins are in a vertex/vertex presentation, a vaginal delivery can be attempted.

After delivery of twin A (ie, the first twin), the cervix often constricts (ie, cervical dilation decreases) due to a lack of engagement (ie, high station) of twin B. The cervix typically returns to complete dilation quickly when the presenting part of twin B descends into the pelvis. After the delivery of twin A and prior to the descent of twin B, an ultrasound is used to reconfirm the presentation of twin B. If twin B still has a vertex presentation and a reassuring fetal heart rate tracing (ie, normal baseline, moderate variability, accelerations, no decelerations), twin B is expectantly managed.

Indications for cesarean delivery of twins include monoamnioticity, malpresentation of twin A, and a nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing of either twin during labor.

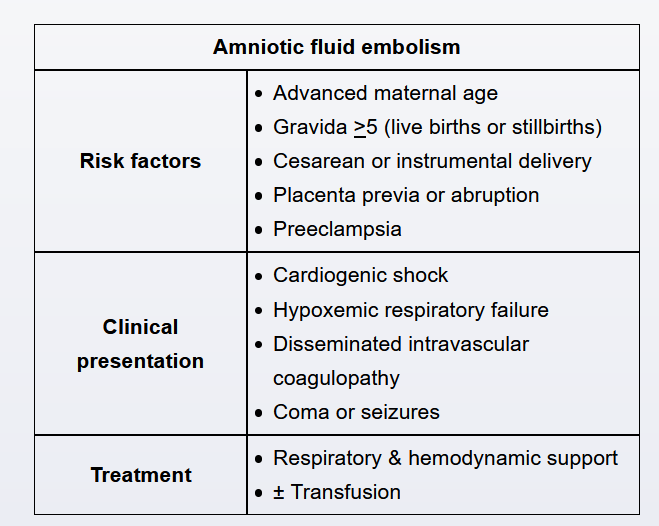

Amnionic fluid embolism

This patient has acute-onset hypoxemia, hypotension, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (eg, hematuria, hemorrhage), a presentation consistent with amniotic fluid embolism syndrome (AFES). AFES, a rare but catastrophic complication of pregnancy, typically occurs during labor or in the immediate postpartum period. Amniotic fluid enters the maternal circulation through the endocervical veins, the placental implantation site, or areas of uterine trauma (eg, cesarean incision site). The amniotic fluid triggers a massive anaphylactoid reaction that results in vasospasm, cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, respiratory failure, seizures, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Risk factors for AFES include cesarean/operative delivery, placenta previa, and abruptio placentae. Treatment is supportive, focused on correcting hypoxemia (eg, oxygen, intubation) and hypotension (eg, vasopressors, transfusion). AFES is associated with a high risk of maternal and neonatal mortality and, among survivors, a high risk of significant neurological sequelae.

FFN

Fetal fibronectin (FFN) in the cervicovaginal discharge of patients at <34 weeks gestation with preterm contractions correlates with a high risk for preterm delivery. However, blood can cause a false positive FFN test result and is not indicated in this patient due to the gestational age.

Big baby C section

To avoid these risks, it is recommended that diabetic patients with an ultrasound estimated fetal weight >4.5 kg (9.9 lb) undergo cesarean delivery at 39 weeks gestation.

Neuraxial analgesia

Pregnant women in active labor receive the most effective pain relief, with a low risk of adverse effects to the mother and fetus, from neuraxial analgesia. Contraindications to neuraxial analgesia in thrombocytopenic patients include severe thrombocytopenia (platelets <70,000/mm3) or rapidly dropping platelet count (often associated with preeclampsia with severe features). In these patients, there is an increased risk of spinal epidural hematoma. In this patient with a platelet count >100,000/mm3 and no evidence of platelet dysfunction (eg, bleeding, bruising), neuraxial analgesia can be administered safely.