Inflammatory Myopathies

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Overview

The inflammatory myopathies include polymyositis (PM), dermatomyositis (DM), immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), and inclusion body myositis (IBM). Although the pathogenesis of these disorders is disparate, they all include immune-mediated muscle inflammation and destruction.

Evaluation of the Patient with Muscle Pain or Weakness

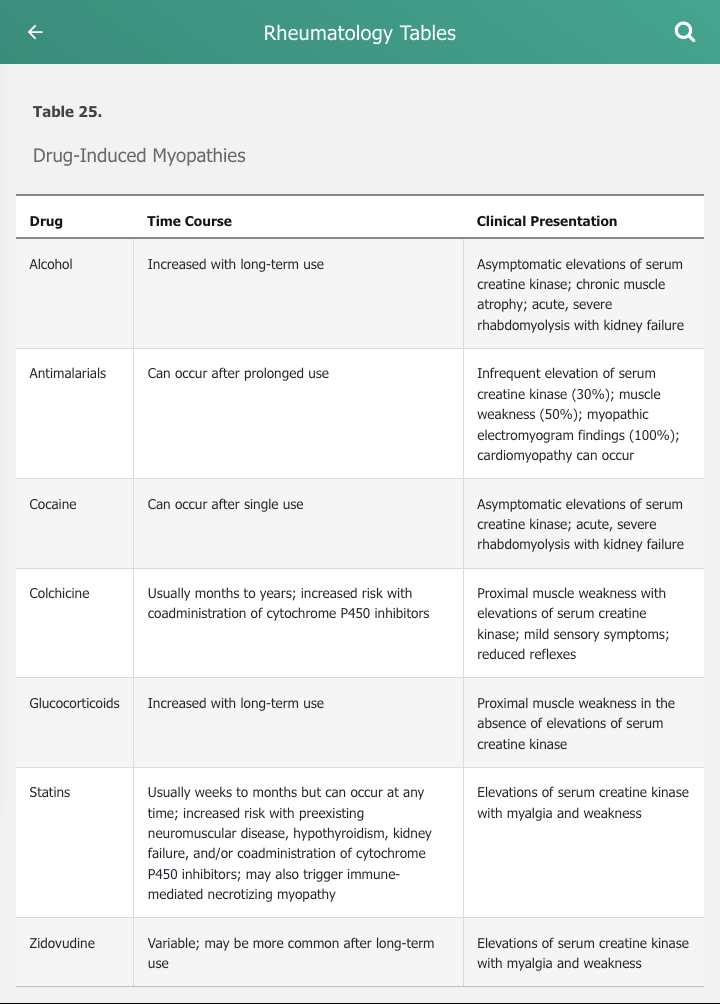

The differential diagnosis of muscle disease is broad and includes hereditary, environmental, infectious, and acquired muscle disease (Table 24). The inflammatory myopathies commonly present with symmetric proximal muscle weakness without substantial muscle pain or tenderness. Serum creatine kinase is almost universally elevated in the inflammatory myopathies and is a marker of muscle damage. The presence of pain or tenderness, however, should prompt considerations of other causes of myopathy. Muscle pain is more common with overexertion, muscle cramps, and injury. Muscle tenderness should prompt consideration of infectious, thyroid, or drug-induced myopathies. Medications and drugs are common causes of myopathy and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the inflammatory myopathies (Table 25).

Weakness is often caused by conditions other than myopathy. Cardiopulmonary disease, malignancy, depression, and deconditioning frequently lead to generalized weakness. Although uncommon, primary neurologic disorders such as spinal muscle atrophies, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis may cause weakness. These diseases are distinguished by involvement of muscle groups other than the proximal muscles, nerve involvement on electromyography (EMG), and a normal serum creatine kinase. Finally, the presence of exercise-induced weakness may point to a metabolic etiology rather than an inflammatory myopathy.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Myopathies

The annual incidence of inflammatory myopathies is between 2 and 10 cases per million. Two peaks of onset occur, with the first in childhood and the second in middle age. A female adult predominance is approximately 2:1 with the exception of IBM, which preferentially affects men.

Genetic factors contribute to the risk of inflammatory myopathies. The clearest association is with HLA DRB1*0301, but alleles vary in populations throughout the world. Except for IMNM, environmental factors have not been clearly implicated. Immune mechanisms that contribute include the presence of T lymphocytic infiltrates in muscle tissue and the expression of autoantibodies in many patients. T- and B-cell proliferation and activation, as well as increased cytokine and chemokine levels in muscle, also occur.

Polymyositis

Clinical Manifestations

Muscle Involvement

The symptoms of PM usually progress slowly over months, although a more rapid onset may occur. Progressive, symmetric, proximal muscle weakness is the classic and dominant feature. Activities such as arising from a chair, stair climbing, and lifting objects above shoulder height are typically affected. Neck flexors are also commonly involved. Muscle pain and tenderness, if present, are mild. Muscle atrophy is a late manifestation. Weakness of respiratory muscles may also occur.

Cardiopulmonary Involvement

Interstitial lung disease, most commonly nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis, occurs in about 10% of patients with PM. It is particularly prominent in the subset of patients with antisynthetase syndrome (also seen in association with dermatomyositis). In addition to interstitial lung disease and myositis, antisynthetase syndrome is characterized by the presence of Raynaud phenomenon, nonerosive arthritis, and mechanic's hands, a dermatologic manifestation characterized by rough, cracked, scaly skin along the lateral aspects of the digits and palms with horizontal lines resembling the weathered hands of a laborer (See MKSAP 18 Dermatology). It can occasionally present as rapidly progressive respiratory failure. Antisynthetase syndrome is associated with autoantibodies against anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, most commonly anti–Jo-1 antibodies.

Mechanic hands with hyperkeratotic, fissured skin on the palmar and lateral aspects of fingers seen in a patient with antisynthetase syndrome.

Mechanic hands with hyperkeratotic, fissured skin on the palmar and lateral aspects of fingers seen in a patient with antisynthetase syndrome.

Cardiac involvement includes conduction system abnormalities that can result in arrhythmias and sudden death. Pericarditis can occur, and pericardial tamponade has been reported. Patients are also at increased risk for myocardial infarction and heart failure, which represent an important cause of morbidity and mortality in PM.

Gastrointestinal Involvement

The striated muscle of the upper two thirds of the esophagus can be affected by PM, leading to dysphagia, dysmotility, and increased risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Dermatomyositis

Clinical Manifestations

In DM, muscle involvement is clinically similar to PM but is almost universally accompanied by a unique constellation of skin findings.

Cutaneous Involvement

Cutaneous involvement of DM can be virtually pathognomic and serve as an indicator of response to therapy (Table 26). Most typical is the Gottron rash (Gottron papules and Gottron sign), erythematous to violaceous areas over the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints (Figure 18). See MKSAP 18 Dermatology for more information.

Muscle Involvement

Similar to PM, the insidious onset of symmetric proximal muscle weakness is most common in DM. Some patients present initially with rash and develop weakness later.

A small percentage of patients may present with skin rash only and never develop muscle involvement (amyopathic DM). At least 6 months without evidence of muscle involvement is necessary before the diagnosis of amyopathic DM can be established.

Cardiopulmonary Involvement

Cardiopulmonary involvement is similar to that seen in PM, but interstitial lung disease is more common in DM (20%-25%). Arrhythmias, complete atrioventricular block, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pericarditis have been reported.

Gastrointestinal Involvement

Gastrointestinal involvement in DM resembles that in PM.

Immune-Mediated Necrotizing Myopathy

IMNM occurs in a small subset of patients with inflammatory myopathy who demonstrate prominent myonecrosis on biopsy without the inflammatory changes typical of the other inflammatory myopathies. An immune-mediated mechanism is suggested by the presence of antibodies to signal recognition particles (SRPs) or 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase. Although statin exposure may result in antibodies to HMG-CoA reductase and IMNM, most patients with statin-induced myopathies have processes other than IMNM (see Table 25).

A small number of patients taking statins develop immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), which can be easily confused with polymyositis. IMNM is thought to occur as a result of an immune response to HMGCR, the pharmacologic target of statins. IMNM can be a paraneoplastic phenomenon related to connective tissue disease, or drug related, most commonly statins. Statin use may initiate or worsen the syndrome. In patients taking statins, myositis may rapidly progress and persist despite drug discontinuation due to this abnormal immune response and is often associated with the production of anti-HMG Co-A reductase antibodies. The histologic finding of necrotic muscle fibers with only minimal inflammatory cells that do not invade the muscle fibers is characteristic of IMNM, and, given the patient's history of exposure to statins, a muscle biopsy and determination of anti-HMG CO-A reductase antibodies will most likely establish the diagnosis. The condition may respond to immunosuppressive therapy.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with IMNM experience severe, rapidly progressive weakness, very high serum creatine kinase levels, and few (if any) extramuscular manifestations.

Muscle Involvement

The characteristic symptom of IMNM is severe proximal muscle weakness, making it difficult to distinguish from PM and DM. Rapidity of onset may provide a clue. In patients with statin-triggered IMNM, the weakness may persist or progress even after statins are discontinued.

Other Organ Involvement

Cardiopulmonary involvement in IMNM is rare. Gastrointestinal involvement has not been reported.

Inclusion Body Myositis

IBM is a uniformly insidious condition and is usually easily distinguishable from PM, DM, and IMNM because of its very slow onset and pattern of muscle involvement.

Clinical Manifestations

Muscle Involvement

Patients typically report a history of preexisting weakness averaging 5 years. Although proximal muscle involvement is present, distal muscle involvement also occurs, distinguishing it from PM and DM. Muscle distribution is typically symmetric, but asymmetry may occur. On physical examination, muscle weakness and atrophy are often present in the hip flexors, quadriceps, finger flexors, and forearm flexors. Serum creatine kinase levels are elevated but are lower than levels seen in PM and DM.

Sporadic IBM is the most common muscle disease in elderly populations, is more common in men than women, and typically develops after age 50 years and does not appear to affect individuals younger than 45 years old. Serum creatine kinase levels are typically less than 10 to 12 times the upper limit of normal. Its insidious onset and distal muscle involvement help to distinguish IBM from the other inflammatory myopathies. The absence of rash helps to exclude dermatomyositis. Electromyogram may show myopathic, neurogenic, or mixed changes with both short and long duration motor unit potentials and spontaneous activity. Diagnosis of IBM is confirmed by muscle biopsy showing muscle fibers containing multiple rimmed vacuoles. Distinguishing IBM from polymyositis is important because IBM is usually not treated with immunosuppressive therapy and has an overall poor response to treatment.

Gastrointestinal Involvement

Up to half of patients with IBM have cricopharyngeal muscle involvement, leading to dysphagia and increased risk of aspiration.

Inflammatory Myopathies and Malignancy

There is an association between risk of malignancy and DM (3- to 12-fold that of age-matched populations) as well as, to a lesser extent, PM. IMNM may occasionally be a paraneoplastic syndrome, but IBM is not strongly associated with malignancy. The risk of malignancy is greatest in the 3 years following the diagnosis of DM or PM. Common associated cancers are ovarian, lung, pancreas, stomach, colon, and lymphoma. Age- and sex-appropriate cancer screening is indicated at the time of diagnosis of DM or PM. Many experts advocate CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, particularly in patients with DM.

Diagnosis

Muscle-Related Enzymes

Elevations of serum muscle enzymes are particularly useful in differentiating intrinsic muscle disease from neurologic causes of weakness. Elevated serum creatine kinase levels are the most sensitive serum indicator of muscle pathology, and levels parallel the severity of involvement. Aldolase can occasionally be elevated when serum creatine kinase levels are normal. Serum aminotransferases and serum lactate dehydrogenase may also be elevated but are nonspecific.

Autoantibodies

Various autoantibodies are used to help diagnose inflammatory myopathies. Some, such as antinuclear antibodies, lack specificity. Others, often termed myositis-specific antibodies, have more diagnostic and prognostic value (Table 27).

Imaging Studies

Although not required to diagnose inflammatory myopathies, MRI is potentially useful in identifying areas of muscle inflammation as an appropriate site for muscle biopsy. MRI is also helpful at identifying muscle atrophy; follow-up with MRI may provide a noninvasive technique to assess therapeutic efficacy.

Electromyography

EMG may show findings highly characteristic of active myositis, although no single finding is pathognomonic. The procedure, however, is invasive and uncomfortable. It may also be normal in the presence of active disease due to the patchy distribution of muscle inflammation (that is, sampling error).

Muscle Biopsy

Muscle biopsy is valuable in diagnosing inflammatory myopathies and for excluding metabolic myopathies, mitochondrial disease, and infection. In PM and DM, features include inflammatory cell infiltrates, muscle fiber necrosis, degeneration, and regeneration.

Muscle biopsy findings in IBM include mononuclear cell infiltrates with unique “rimmed” vacuoles without muscle cell necrosis; electron microscopy may show inclusion bodies.

Skin Biopsy

Skin biopsy is useful in diagnosing DM. Light microscopy findings include mild epidermal atrophy, vacuolar changes at the dermal-epidermal junction, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, and increased dermal mucin. However, these findings may be similar to those of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Diagnosis of amyopathic DM is made with skin biopsy confirmation of DM in the setting of at least 6 months of normal muscle strength, muscle enzymes, normal EMG, and, if performed, normal muscle biopsy.

Management

Glucocorticoids are the cornerstone of therapy for the inflammatory myopathies except for IBM. Prolonged exposure to high-dose glucocorticoids, particularly in the elderly, can be associated with the appearance of steroid-induced myopathy that may cause new proximal muscle weakness in a patient who had previously been improving; reduction in dose is appropriate management.

Distinguishing between glucocorticoid-induced myopathy and active inflammatory myopathy is important, particularly in older patients for whom long-term glucocorticoid side effects can be particularly debilitating. The history is suggestive of glucocorticoid myopathy when a patient has been started on high-dose glucocorticoids within a few months, has cushingoid features, and has normal serum creatine kinase levels. No single feature is diagnostic on electromyogram (EMG) or muscle biopsy.

Additional immunosuppressives are often required to control inflammation or to serve as glucocorticoid-sparing agents; methotrexate and azathioprine are most frequently used. DM and PM are most responsive to immunosuppression, although DM is more responsive than PM. For patients with statin-induced IMNM, statin discontinuation is mandatory but not sufficient, and immunosuppressive treatment is required. IBM usually does not respond to immunosuppression, and therapeutic trials should be undertaken only in selected patients and discontinued if benefit is not appreciated. Other immunosuppressives, including mycophenolate mofetil and rituximab, have been used in refractory DM, PM, and IMNM. Intravenous immunoglobulin may be a reasonable alternative in DM.

Physical therapy may help maintain muscle function and should be used in all patients.

Prognosis

The prognosis in DM/PM varies from near-complete resolution to severe, treatment-resistant disease with marked functional impairment and early mortality. Prolonged symptoms prior to treatment, greater weakness at presentation, extensive multisystem disease, and the co-occurrence of malignancy confer a poorer prognosis. The degree of serum creatine kinase elevation is not predictive of outcome. Myositis-specific antibodies may have prognostic value. Patients with anti–Jo-1 antibodies have worse outcomes (due to interstitial lung disease), whereas those with anti-Mi-2 antibodies often respond completely, despite a rapidly progressive course of DM.

Patients with IMNM frequently respond well to statin discontinuation (if appropriate) and immunosuppression.

Given the lack of effective treatment, patients with IBM typically demonstrate a slow and gradual loss of function, with progression to wheelchair dependence within 10 to 15 years.