Infectious Gastrointestinal Syndromes

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Overview

Diarrhea, defined as three or more unformed stools daily or a quantity greater than 250 grams daily, is a major public health concern. Diarrhea lasting less than 14 days is considered acute, 14 to 30 days is persistent, and longer than 30 days is chronic. Acute infectious diarrheal presentations include acute gastroenteritis, with associated fever, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, tenesmus, and crampy abdominal pain. Chronic infectious diarrhea is most likely due to parasites. Not all diarrheal presentations are infectious, such as inflammatory bowel disease, endocrine disorders, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and medication-induced diarrhea.

Patients with mucoid or bloody diarrhea, fever, significant abdominal cramping, or suspected sepsis and those who are immunocompromised or require hospitalization should have diagnostic assessment of their stool to guide antimicrobial use. Additional areas of concern include symptoms that persist for longer than 1 week or outbreak settings where day-care participants, institutional residents, health care providers, or food handlers are involved. Increasingly more available, rapid multiplex molecular gastrointestinal assays that identify common bacterial, parasitic, and viral pathogens from a single stool sample are generally more sensitive than historical stool culture and microscopy with special stains. (Table 48). Isolates from culture, however, can provide antibiotic susceptibilities and strain-typing information in outbreak situations that are not available from culture-independent diagnostic assays.

Most healthy patients with watery diarrhea of less than 3 days' duration can be treated with supportive care and no antibiotic therapy or diagnostic assessment. When acute diarrhea is debilitating (moderate or severe) and associated with travel, antibiotic therapy with a fluoroquinolone, azithromycin, or rifaximin is recommended. If a patient has dysentery with visible mucus or blood in the stool and a temperature less than 37.8 °C (100 °F), then microbiologic assessment is recommended to guide therapy. When severe debilitating disease is present with temperatures of 38.4 °C (101.1 °F) or greater, microbiologic assessment should be considered, followed by empiric azithromycin treatment (see Table 48). Antimotility agents, such as loperamide, are discouraged in patients with inflammatory diarrhea (fever, abdominal pain, bloody stools) or _Clostridium difficile–_associated infection.

Campylobacter Infection

Campylobacter species–associated gastroenteritis is usually foodborne, often secondary to consumption of inadequately cooked poultry. The incubation period is several days, and symptoms typically include diarrhea (visibly bloody in <15% of patients), crampy abdominal pain, and fever. Stool culture can confirm the diagnosis, and blood cultures can identify extraintestinal disease. Diarrhea usually resolves spontaneously without antibiotics. Patients who have severe disease (bloody stools, bacteremia, high fever, or prolonged [>1 week] symptoms) or are immunocompromised should receive antibiotic therapy. When indicated, macrolide therapy is preferred empirically because of increasing fluoroquinolone resistance. Possible post–Campylobacter infection complications include irritable bowel syndrome, reactive arthritis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Shigella Infection

Shigella infection is more commonly spread from person to person than by consumption of contaminated food or water. Fewer than 100 bacteria can cause infection, and the incubation period is approximately 3 days. Patients typically present with crampy abdominal pain, tenesmus, small-volume bloody and/or mucoid diarrhea, high fever, and (possibly) vomiting. More serious complications include bacteremia, seizures, and intestinal obstruction and perforation. Potential postinfectious sequelae include hemolytic uremic syndrome, reactive arthritis, and irritable bowel syndrome. Routine stool culture or molecular testing will establish the diagnosis. Invasive disease in patients with severe infection can also be established with blood cultures. Treatment with antibiotic agents is recommended for those with severe illness (that is, those who require hospitalization, have invasive disease, or have complications of infection) and those who are immunocompromised. Public health officials may also recommend treatment when outbreaks occur. Antibiotic susceptibilities should be obtained to determine treatment because of increasing resistance rates against the quinolones.

Salmonella Infection

Salmonella infection can be typhoidal (serotypes Paratyphi or Typhi) or nontyphoidal. The typhoidal types cause enteric fever, a syndrome consisting of fever, abdominal pain, rash, hepatosplenomegaly, and relative bradycardia. This type of infection is uncommon in the United States, with most affected persons traveling to endemic areas and ingesting contaminated water or food. In contrast, nontyphoidal Salmonella serotypes are the most common bacterial cause of foodborne illness in the United States.

Nontyphoidal Salmonella infection usually results from ingesting fecally contaminated water or food of animal origin, including poultry, beef, eggs, and milk. Contact with infected animals (including pet reptiles, turtles, and snakes; farm animals; amphibians; and rodents) is a much less common mode of transmission. The incubation period is usually less than 3 days, and symptoms typically include crampy abdominal pain, fever, diarrhea (not usually visibly bloody), headache, nausea, and vomiting. Diagnosis can be made by stool culture or molecular testing. Illness is usually self-limited, although bacteremia with extraintestinal infection (involving vascular endothelium, joints, or meninges) may occur; Salmonella osteomyelitis also can occur and is classically associated with sickle cell disease. Severe invasive disease is more likely in infants, older adults, patients with cell-mediated immunodeficiency, and patients with hypochlorhydria. Reactive arthritis is a potential postinfection complication.

Most uncomplicated Salmonella infections in adults younger than 50 years resolve within 1 week and require only supportive care. Antibiotic agents are typically reserved for patients with more serious illness (including severe diarrhea requiring hospitalization, bacteremia, or high fever or sepsis) and those at high risk for severe complicated invasive disease (including infants, patients 50 years and older, or those with prosthetic materials, significant atherosclerotic disease, or immunocompromising conditions such as HIV infection. When empiric treatment is indicated, fluoroquinolones (such as levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin) are most likely to be effective, but azithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and amoxicillin also are potentially active agents. A fluoroquinolone, third-generation cephalosporin (such as ceftriaxone), or both are often initiated as empiric therapy for patients with severe disease requiring hospitalization. Local antibiotic susceptibilities of Salmonella should dictate choice of empiric therapy.

Escherichia coli Infection

Although Escherichia coli are normal inhabitants of the intestinal microbiome, some strains become enteropathogenic by using different mechanisms of infection (Table 49).

Enterotoxigenic E. coli infection (ETEC) is the most common cause of travelers' diarrhea. ETEC results from ingestion of water or food contaminated with stool and has an incubation period of 1 to 3 days. Enterotoxins cause watery diarrhea with associated abdominal cramping, nausea, and low-grade or no fever. Usually self-limiting, the illness resolves after approximately 4 days. Hydration and empiric antibiotic therapy with fluoroquinolones, azithromycin, or rifaximin are recommended in travelers with ETEC when symptoms restrict activities.

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strains, such as -0157:H7 and -0104:H4, produce a Shiga-like toxin that can cause hemorrhagic colitis. EHEC bacteria are found in cow intestines and are transmitted by ingestion of undercooked hamburgers or fecally contaminated food (such as spinach, lettuce, fruit, milk, and flour) and water; fecal-oral transmission through exposure to infected animals at petting zoos is also possible. The incubation period is 3 to 4 days, and patients typically have visibly bloody diarrhea, crampy abdominal pain, and no fever, the latter a distinguishing feature from other causes of bloody diarrhea. Alerting the laboratory about the symptoms is recommended so that appropriate media, antigen testing, and Shiga toxin assays can be performed. Hemolytic uremic syndrome is found in less than 10% of patients infected with EHEC and manifests as microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and kidney injury. Treatment of EHEC infection is primarily supportive; antibiotics and antimotility agents may increase the risk of developing hemolytic uremic syndrome and do not appear to shorten the duration of infection.

Yersinia Infection

Most diarrheal illness due to Yersinia species is caused by Yersinia enterocolitica, usually after ingestion of contaminated food, particularly undercooked pork. Patients with iron overload states, including hemochromatosis, are at increased risk for infection (including bacteremia) owing to the siderophilic characteristics of Yersinia species. The incubation period is approximately 5 days, and patients typically have fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea (possibly bloody), and (sometimes) nausea and emesis at presentation. The organism has tropism for lymphoid tissue (including tonsillar tissue and mesenteric lymph nodes), which results in pharyngitis or right lower-quadrant pain mimicking appendicitis. Postinfection complications include erythema nodosum and reactive arthritis. The diagnosis is confirmed by molecular testing of stool or by culture of stool, blood, a throat swab, or infected tissue; the testing laboratory should be alerted when Yersinia enterocolitica infection is suspected so that optimal media and enrichment conditions are applied. When treatment is indicated, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (first choice) or a fluoroquinolone (such as ciprofloxacin) or a third-generation cephalosporin is recommended.

Vibrio Infection

In the United States, Vibrio parahaemolyticus is the most common Vibrio species to cause gastrointestinal illness, usually after consumption of contaminated or undercooked oysters and other shellfish. The incubation period is approximately 1 day; infected patients typically report diarrhea (not commonly bloody), fever, nausea or emesis, and crampy abdominal pain at presentation. V. parahaemolyticus can cause septicemia in patients who have liver disease, which may lead to secondary necrotizing skin infections. Severe noninvasive gastrointestinal illness can be treated with doxycycline, although fluoroquinolones and macrolides also can be used. Patients with septicemia require more aggressive combination therapy, typically with doxycycline plus ceftriaxone.

Clostridium difficile Infection

Clostridium difficile is the leading cause of hospital-acquired infectious diarrhea and results from fecal-oral transmission. The number of these infections reported in the United States has increased significantly since the year 2000, owing in large part to the emergence of a hypervirulent strain. Risk factors for infection include exposure to antibiotic and chemotherapeutic agents, older age, presence of inflammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal surgery, and (possibly) gastric acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors. Antibiotic stewardship is paramount in reducing incidence of infection, and hand washing with soap and water is the gold standard for infection control; alcohol-based gels do not eliminate spores.

Asymptomatic colonization can occur; for those with pathologic infection, the incubation period can be as long as 6 weeks after perturbation of the intestinal flora with antibiotic agents. Community-acquired infections without previous exposure to health care settings, antibiotic agents, or both have been increasingly reported.

Clostridium difficile produces both an enterotoxin (toxin A) and a cytotoxin (toxin B) that are pathogenic. Symptomatic patients typically have watery diarrhea (rarely bloody), crampy abdominal pain, malaise, and sometimes nausea and fever. Abnormal laboratory study findings are nonspecific but can include leukocytosis, an elevated creatinine level, and hypoalbuminemia. Radiographic imaging, also nonspecific, may demonstrate colonic wall thickening, mucosal edema, fat stranding, and megacolon. Colonoscopy, although not a routine diagnostic modality, may visualize pseudomembranes associated with infection.

Diagnosis is usually established by testing unformed stools from persons not taking laxatives who have unexplained new-onset diarrhea occurring three or more times daily. Although highly specific and rapid, enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing for presence of toxin A or B lacks sensitivity. EIA testing for presence of glutamate dehydrogenase, an antigenic protein present in all C. difficile isolates, is quite sensitive but lacks specificity. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for C. difficile toxin genes is rapid, highly sensitive, and specific. If NAAT is not used as a stand-alone technique, then combining EIA tests for glutamate dehydrogenase plus toxin (discordant results require polymerase chain reaction testing for resolution) or NAAT plus toxin can be performed.

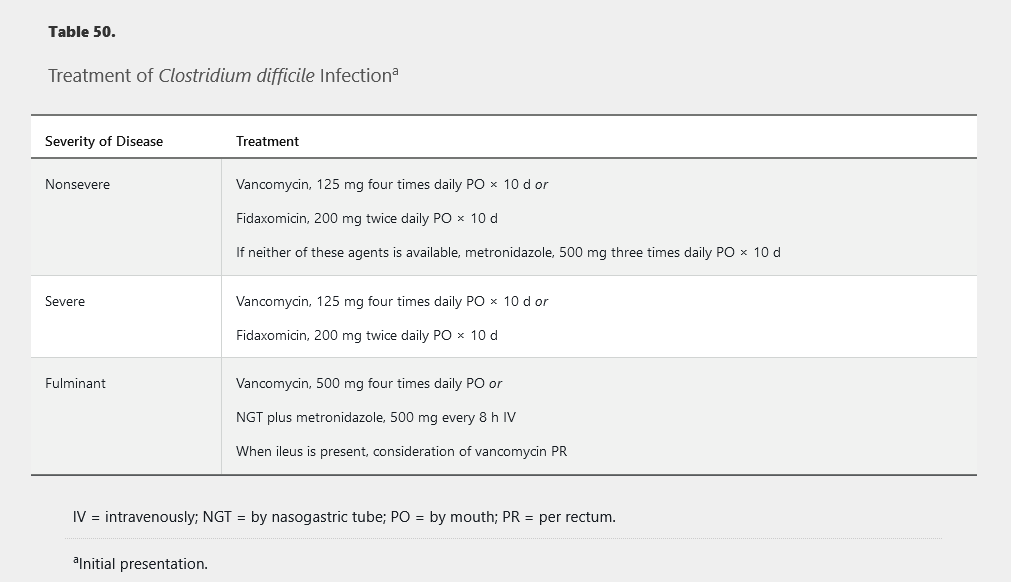

In all infected patients, the antibiotic agent associated with the infection should be stopped if possible. Treatment is otherwise dictated by severity of disease (Table 50). Severe disease is supported clinically by a leukocyte count of 15,000/µL (15 × 109/L) or greater or a serum creatinine level greater than 1.5 mg/dL (133 µmol/L). Oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin for 10 days is recommended. For nonsevere disease, defined as C. difficile infection that is neither severe nor fulminant, oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin for 10 days is recommended. If neither of these agents is available, oral metronidazole for 10 days can be used.

Fulminant disease is defined as severe C. difficile infection with associated shock, ileus, toxic megacolon, ICU admission, elevated serum lactate level, hypotension, altered mental status, or organ failure. Higher-dose oral or nasogastric vancomycin, intravenous metronidazole, and (possibly) vancomycin enema (when ileus is present) are recommended. Patients with fulminant disease warrant surgical evaluation.

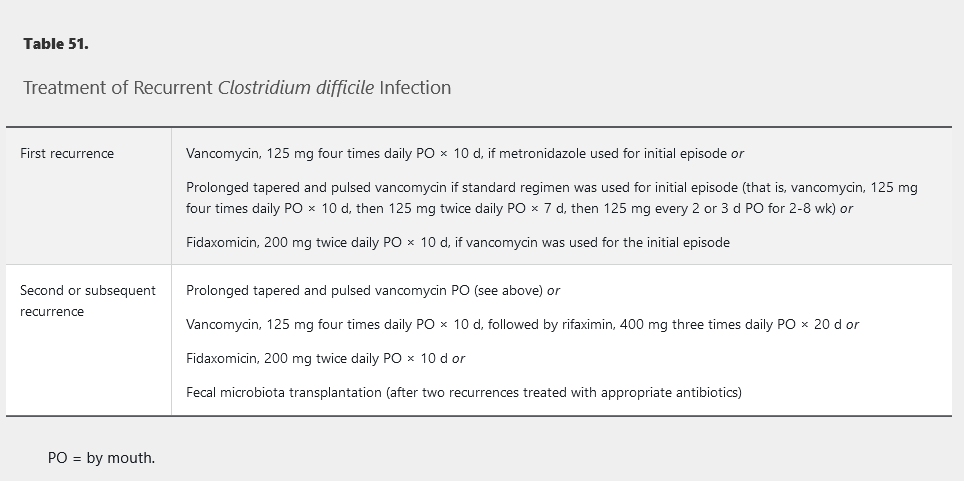

Recurrent infection is reported in as many as 25% of patients, and treatment recommendations are found in Table 51. Studies have shown that fecal microbiota transplantation is effective in the management of patients with multiple recurrences. Retesting stool for C. difficile after treatment for evidence of cure in patients who have no symptoms is not recommended.

Viral Gastroenteritis

Viruses are responsible for acute gastroenteritis in most patients. Rotavirus infects young children, and noroviruses, which are estimated to cause more than 50% of foodborne gastroenteritis in the United States, affect all ages. Norovirus outbreaks on cruise ships and in schools and other institutionalized settings are well documented. Transmission from person to person is primarily fecal-oral. Highly contagious infection can develop after ingestion of fewer than 100 viral particles. The incubation period is typically less than 2 days, and infected patients typically have watery diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and fever at presentation. Infection is usually self-limited and requires supportive care because of the lack of effective antiviral agents. Diagnostic molecular testing is available. Viral shedding persists for as long as 2 weeks after symptom resolution, which contributes to its high infectivity.

Parasitic Infection

Parasitic infection should be considered in patients with persistent or chronic diarrhea. Immunosuppressed persons are at increased risk for more chronic and severe infection.

Giardia lamblia Infection

Giardia lamblia is the most common parasitic pathogen in the United States. Cysts from infected animals are excreted in stool into reservoirs of natural fresh water, and subsequent ingestion of contaminated water (or food) can lead to human infection. Secondary spread from person to person via fecal-oral transmission is also possible because cysts may be excreted for many months. Persons at risk for infection include international outdoor travelers, children in day-care centers, immunocompromised hosts (particularly those with humoral immunodeficiency), and persons engaged in sexual activity that includes oral-anal contact. The incubation period ranges from 1 to 3 weeks. More than half of infected patients are asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients typically report watery diarrhea that is fatty and foul smelling, flatulence, bloating, nausea, and crampy abdominal pain; fever is uncommon. Symptoms can last for several weeks until spontaneously resolving; chronic infection may develop, particularly in persons with hypogammaglobulinemia. EIA and molecular testing of stool is more sensitive than stool microscopy for confirming the diagnosis. Treatment is recommended for symptomatic patients; metronidazole, tinidazole, or nitazoxanide can be used. Postinfection lactose intolerance is common and may be mistaken for recurrent or resistant Giardia infection.

Cryptosporidium Infection

Cryptosporidium species can infect humans and other mammals. Infection occurs through consumption of fecally contaminated water or food or through close person-to-person or animal-to-person transmission. Municipal water supplies and swimming pools can be a source of infection because the thick-walled oocysts are chlorine resistant and can evade filtration. This parasite is highly infectious; ingestion of fewer than 50 oocysts may result in infection. The incubation period is 7 days. Although some infected patients will be asymptomatic, symptomatic patients typically report watery diarrhea, crampy abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, malaise, fever, dehydration, and weight loss. Symptoms usually last less than 2 weeks before spontaneously resolving in immunocompetent hosts. Immunocompromised patients, in particular patients with AIDS, can develop serious and prolonged infection. Diagnosis can be established microscopically by visualization of oocysts with modified acid-fast staining, molecular testing, and enzyme or direct fluorescent immunoassay testing. Treatment for immunocompetent patients usually consists of supportive care. When antimicrobial agents are considered for severe or prolonged infection, nitazoxanide is recommended. In HIV-infected patients, antiretroviral therapy is most effective in resolving infection. Nitazoxanide also can be considered when supportive care does not result in symptom resolution.

Amebiasis

Entamoeba histolytica is the parasitic organism responsible for amebiasis. In the United States, most infections are diagnosed in travelers returning from visits to unsanitary tropical or developing countries, immigrants from these areas, persons in institutionalized settings, or those who practice oral-anal sex. Amebiasis is highly infectious, with ingestion of only a small number of infective cysts in contaminated water or food needed for infection. The incubation period is 2 to 4 weeks. Most infections are asymptomatic, but some patients develop diarrhea with visible blood, mucus, or both and associated abdominal pain, fever, and weight loss. Colonic perforation, peritonitis, and death may complicate more fulminant infections. Risk factors for severe infection in adults include immunodeficiency. Diagnosis can be established microscopically by visualization of cysts or trophozoites, immunoassay testing, molecular testing, and serologic antibody testing, although the latter technique does not distinguish current from remote infection. Treatment is recommended for all infected patients. In symptomatic patients, treatment with metronidazole or tinidazole is recommended initially for parasitic clearance followed by an intraluminal amebicide, such as paromomycin or diloxanide, for cyst clearance. In asymptomatic infections, an intraluminal agent for eradication of cysts is recommended.

Cyclospora Infection

Cyclospora infections are typically acquired after consumption of food or water that is fecally contaminated with Cyclospora oocysts. In the United States, most of these infections have been traced to imported fresh produce from tropical areas or have occurred in persons who have traveled to areas of endemicity. The incubation period is approximately 1 week. Infected patients typically report watery diarrhea, decreased appetite, weight loss, crampy abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, nausea, fatigue, and (sometimes) fever. Symptoms can last for several weeks and may be more pronounced in HIV-infected patients. Diagnosis is typically established microscopically by visualization of oocysts with modified acid-fast staining, microscopy with ultraviolet fluorescence, or molecular testing.

The recommended treatment is one double-strength tablet of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole taken orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states no effective alternative treatments have been identified for persons who are allergic to or cannot tolerate trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; observation and symptomatic care is recommended for those patients.