Infectious Arthritis

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

Infectious arthritis typically presents with pain, swelling, warmth, and erythema of the affected joint, accompanied by fever and constitutional symptoms. Knee infection is common, but any joint may be affected. Previously damaged joints are at increased risk for involvement. Monoarthritis or new inflammation of a single joint in a patient with well-controlled inflammatory arthritis should prompt evaluation for infection.

Physical examination commonly shows functional loss of both active and passive range of motion in addition to signs of inflammation. Skin examination can reveal signs suggesting gonococcal infection (pustular skin lesions) or portals of entry (scratches, bites, or thorns).

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

In patients with suspected infectious arthritis, the most important diagnostic procedure is expeditious arthrocentesis. The synovial fluid should be sent for Gram stain, culture (bacterial and, when indicated, mycobacterial and/or fungal), leukocyte count, and crystal analysis. Synovial fluid levels of glucose, lactate dehydrogenase, and total protein do not aid in diagnosis and should not be obtained. Depending upon the clinical picture, the fluid may be sent for polymerase chain reaction to detect Mycobacteria or Borrelia burgdorferi DNA.

Bacterially infected synovial fluid is cloudy and less viscous than that seen in noninflammatory arthritis. Elevated synovial fluid leukocyte counts are typically greater than 50,000/µL (50 × 109/L) and often exceed 100,000/µL (100 × 109/L), with a polymorphonuclear cell predominance. Such high leukocyte counts may occur in other conditions (for example, crystal arthropathies) but should be presumed infectious until proven otherwise. Notably, the presence of crystals does not exclude the possibility of co-infection. Patients with gonococcal, mycobacterial, or fungal infections, injection drug users, or those who are immunocompromised may have lower synovial fluid leukocyte counts. A positive Gram stain for bacteria should be considered definitive, but the sensitivity of the test is inadequate for a negative result to rule out infection when suspicion is high. Synovial fluid cultures are usually positive in bacterial infections unless antibiotics were administered prior to arthrocentesis. The peripheral blood leukocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein are often elevated; however, normal levels do not exclude the diagnosis, and elevated levels may occur in inflammatory arthritis and other conditions.

Blood cultures should always be drawn before antibiotic administration. When gonococcal arthritis is suspected, urogenital, rectal, and pharyngeal specimens should also be obtained for nucleic acid amplification testing.

Plain radiographs are usually normal early in the course of the infection, but baseline films are helpful to identify other diseases or contiguous osteomyelitis. Later radiographs (weeks to months) often show nonspecific changes. In advanced infection, periosteal reaction, marginal or central erosions, and subchondral bone destruction may be seen. Bony ankylosis is a late sequel. In joints that are difficult to evaluate clinically or have complex anatomic structures, ultrasonography, CT, and MRI can delineate the extent of the effusion and identify early bony changes.

Causes

Infection with Gram-Positive Organisms

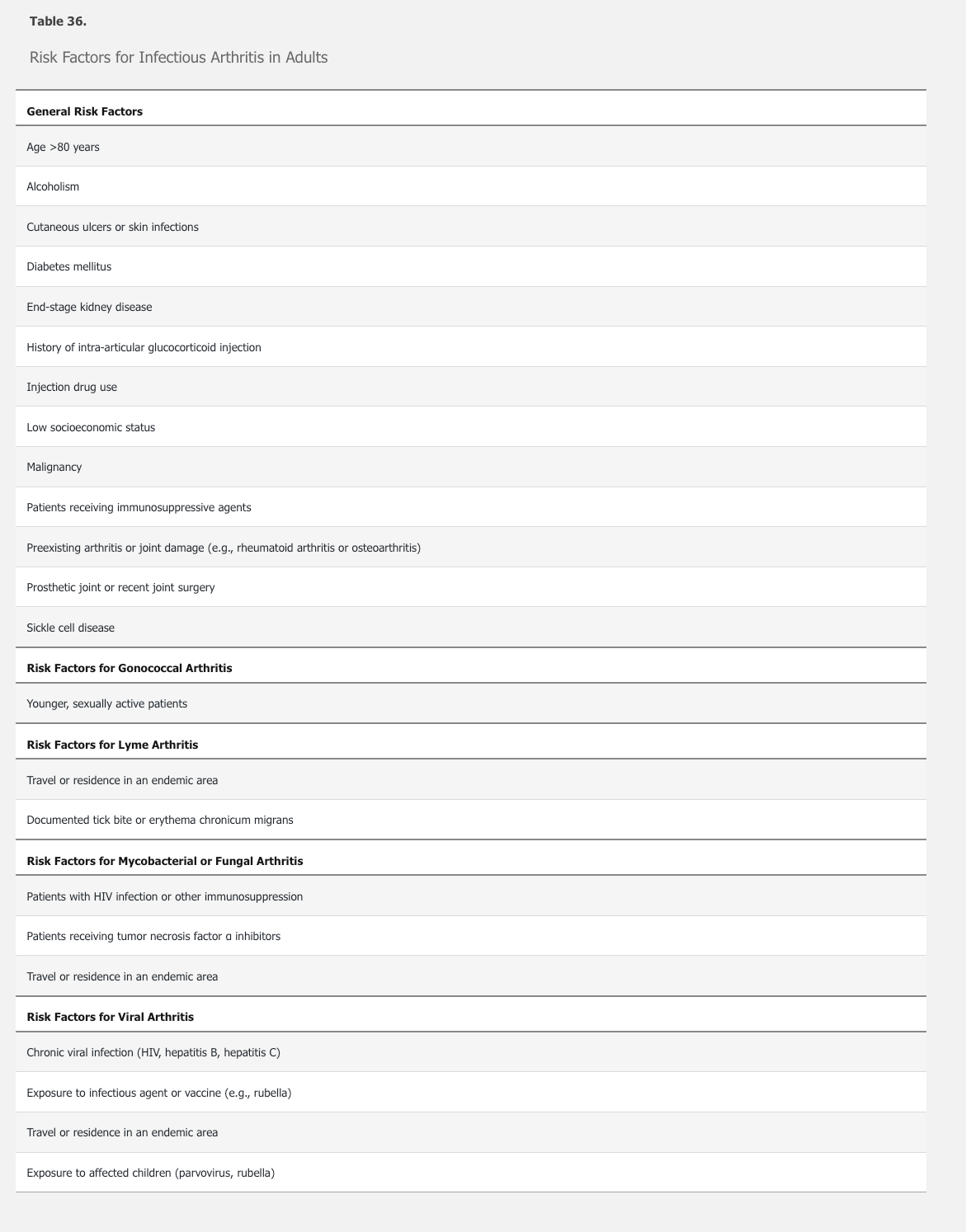

Bacterial arthritis is a medical emergency requiring immediate diagnosis and treatment. Risk factors include an immunocompromised state (including diabetes mellitus), injection drug use, joint surgery, and having a prosthetic joint. A recent “dirty” skin break may be a contributing factor. Infections occur very rarely after invasive procedures such as arthrocentesis or joint injection (Table 36). Most joint infections are monoarticular and derive from hematogenous seeding of synovium. Polyarticular infectious arthritis may occur in injection drug users, those with systemic inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, and in patients with overwhelming sepsis.

Approximately 75% of adult nongonococcal infectious arthritis is caused by gram-positive cocci, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most frequent microorganism in both native and prosthetic joints. Staphylococcus epidermidis infections occur more commonly in prosthetic than in native joints.

Infection with Gram-Negative Organisms

Disseminated Gonococcal Infection

Neisseria gonorrhoeae most typically occurs in younger, sexually active individuals. Disseminated infection occurs in 1% to 3% of patients infected with N. gonorrhoeae, with arthritis a common feature.

Disseminated gonococcal infection may present in one of two ways, although there may be overlap. The first is the arthritis-dermatitis syndrome, a triad of tenosynovitis, dermatitis (usually painless pustular or vesiculopustular lesions) (Figure 26), and polyarthralgia without frank arthritis. Fever, chills, and malaise are common. Inflammation of multiple tendons of the wrists, fingers, ankles, and toes distinguishes this syndrome from other forms of infectious arthritis. The second presentation is a purulent arthritis, usually without associated skin lesions or fever. Patients present with acute onset of mono- or oligoarthritis; the knees, wrists, and ankles are most commonly involved.

Patients with the arthritis-dermatitis syndrome are more likely to have positive blood cultures, whereas those with purulent arthritis are more likely to have positive synovial fluid cultures. Nucleic acid amplification testing should also be obtained on samples from genital, rectal, and pharyngeal sites.

Nongonococcal Gram-Negative Organisms

Aerobic gram-negative bacilli are the predominant cause of nongonococcal gram-negative joint infections. Predisposing factors include injection drug use, advanced age, and an immunocompromised state. Pseudomonas aeruginosa can be seen in infection related to injection drug use. Patients with sickle cell anemia may become infected with Salmonella. Gram-negative anaerobes account for only 5% to 7% of bacterial arthritis cases, most commonly in prosthetic joint infections and/or immunocompromised hosts.

Lyme Arthritis

Although arthralgia and myalgia often occur at the earlier stages of Lyme disease, Lyme arthritis is a late-stage manifestation. It is typically monoarticular or oligoarticular, most commonly in the knee. It should be suspected in patients who may have had untreated or incompletely treated Lyme disease, although not all patients will have a history compatible with prior Lyme disease. All patients with Lyme arthritis, however, should have positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot serologies; this is the major means of establishing the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis. Additionally, B. burgdorferi DNA can be detected by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The most common musculoskeletal manifestation of tuberculosis is vertebral osteomyelitis (Pott's disease), usually resulting from the hematogenous spread of Mycobacterium tuberculosis into the cancellous bone tissue of the vertebral bodies. Patients usually have a primary pulmonary focus or extrapulmonary foci such as the lymph nodes. Predisposing factors for skeletal tuberculosis include previous tuberculosis infection, malnutrition, alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, and HIV infection. The onset of symptoms is commonly insidious, and disease progression is slow, sometimes resulting in delayed diagnosis. The lower thoracic spine is the most frequently involved segment; common symptoms are back pain, fever, weight loss, and neurologic abnormalities. Paraplegia is the most devastating complication. Diagnosis is suggested by typical clinical presentation, along with evidence of past exposure to tuberculosis or concomitant visceral tuberculosis, and findings on neuroimaging modalities. Bone tissue or abscess samples from needle or surgical biopsy stained for acid-fast bacilli and/or positive cultures are most helpful in diagnosis.

Middle aged immigrant with weight loss, upper back pain, decreased sensation, granuloma on CXR, vertebral body collapse

Peripheral arthritis may also occur and typically presents with chronic pain in a single weight-bearing joint such as the knee, with only limited swelling. Concurrent pulmonary tuberculosis is present in a minority of these patients. Musculoskeletal tuberculosis infections are chronic and indolent; laboratory indicators of inflammation may be normal. Synovial fluid shows only nonspecific inflammation, and radiographic abnormalities may be delayed. Synovial biopsy is usually necessary for diagnosis because the yield of synovial fluid smear and culture is less than 50%.

Fungal Infections

Fungi are uncommon but important causes of bone and joint infections. Risk factors include immunosuppression and exposure to the fungi in endemic areas. Travel and immigration have broadened the risk of some fungal infections to non-endemic areas. Fungal joint infection may be indolent and more difficult to diagnose than other bone and joint infections. Fungal causes of osteomyelitis and arthritis include coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, candidiasis, and sporotrichosis. Fungal arthritis is usually a result of hematogenous dissemination but can occur after direct inoculation of the joint. Diagnosis of some fungal infections (for example, blastomycosis and sporotrichosis) can be made by synovial fluid examination and culture, whereas serologic testing and synovial biopsy may be needed for other organisms (such as Coccidioides). Synovial fluid leukocyte counts vary.

Viral Infections

HIV

HIV infection is associated with several musculoskeletal disorders, including painful articular syndrome, HIV-associated arthritis, reactive arthritis, infectious arthritis, and diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome (DILS). Painful articular syndrome consists of bone and joint pain, especially in the lower extremities in an asymmetric pattern, lasting less than 24 hours. HIV-associated arthritis is a nondestructive arthritis that involves joints of the lower extremity in an oligoarticular pattern and usually lasts less than 6 weeks. Reactive arthritis is the primary form of spondyloarthritis seen in patients with HIV infection and is likely due to a response to other sexually transmitted or enteric infections, rather than the HIV itself. Reactive arthritis in HIV may take a chronic relapsing course and may be accompanied by enthesopathy and mucocutaneous manifestations. Psoriatic arthritis is not more common but is often more severe in patients with HIV infection, with disabling enthesitis and joint erosion as well as axial involvement including sacroiliitis. DILS is a rare condition that resembles Sjögren syndrome but with CD8 rather than CD4 cell infiltration.

Hepatitis

Hepatitis B virus infection causes a self-limited arthritis in up to 25% of infected patients during a prodromal stage prior to the onset of jaundice. Joint involvement can be sudden and severe, with a pattern that is usually symmetric, but can be migratory or additive. Hand and knee joints are most often affected; wrists, ankles, elbows, shoulders, and other large joints may be involved as well. Morning stiffness is common. Fusiform swelling of the small joints of the hand may be found on physical examination. Patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection may have recurrent but self-limited polyarthralgia or polyarthritis; it is not known to progress or cause joint damage. Both hepatitis B and C virus infection may be accompanied by the presence of rheumatoid factor, which can cause diagnostic confusion.

Acute hepatitis C virus infection can cause acute-onset polyarthritis, including the small hand joints, wrists, shoulders, knees, and hips. One third of patients have an oligoarthritis. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection is often associated with circulating immune complexes, which may produce the clinical syndrome of mixed essential cryoglobulinemia (arthritis, glomerulonephritis, and vasculitis).

Parvovirus B19

Up to 60% of adults with parvovirus B19 experience arthritis. It often presents acutely, is symmetric and polyarticular, and typically involves the proximal small joints of the hands. Parvovirus B19 arthritis should be suspected when appropriate clinical features are present in someone who has exposure to children, such as teachers and caregivers. Acute parvovirus infection is diagnosed by detecting anti-parvovirus IgM antibodies in the serum. Anti-parvovirus IgG antibodies are highly prevalent in the general population and indicate prior infection. Joint symptoms may persist for weeks to months.

Rubella

Arthritis is uncommon in childhood rubella infection, but up to 60% of adults with rubella develop joint symptoms, mainly arthralgia. Joint involvement is usually symmetric and migratory, with resolution of most symptoms within 2 weeks. The small joints of the hands, wrists, elbows, ankles, and knees are most commonly affected. Tenosynovitis and carpal tunnel syndrome also occur. The pathogenesis of rubella arthritis is thought to be due to immune complexes and/or persistence of the virus in synovial cells or joint macrophages. Diagnosis is usually made by detection of IgM antirubella antibodies; the virus may also be cultured from the nasopharynx or joint tissues. Joint fluid findings are inflammatory.

Mosquito-Borne Viruses

Zika, dengue, and chikungunya viruses are transmitted by Aedes mosquitos in tropical areas. Zika also can be vertically and sexually transmitted, and localized transmission in the southern United States is now reported. All of these viruses can cause musculoskeletal symptoms in addition to fever, rash, and headache. In chikungunya, arthritis is a predominant feature; patients may experience synovial thickening and tenosynovitis, often involving the fingers and wrists. Zika may also manifest with a symmetric polyarthritis, whereas dengue tends to produce more arthralgia. The musculoskeletal symptoms of Zika and dengue tend to subside within a couple of weeks, whereas those of chikungunya usually continue longer, resembling rheumatoid arthritis (without rheumatoid factor or anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies) in some cases. Diagnosis of these mosquito-borne diseases is based on clinical features and serologic testing. Polymerase chain reaction testing on blood samples is also available.

Prosthetic Joint Infections

Bacterial infection complicates 1% to 3% of total knee and hip replacements; higher rates are seen in immunocompromised patients and those with rheumatoid arthritis. Infection with gram-positive organisms such as S. aureus is most common. Prosthetic joint infections are divided into early onset (<3 months after placement), delayed (3 to 24 months postsurgery), and late onset (>24 months after placement). Early and delayed infections are usually related to surgical contamination at the time of the implantation, whereas late infections result from hematogenous seeding of the joint. Early and late prosthetic joint infections typically present with pain, warmth, effusion, and fever. Peripheral leukocyte count and inflammatory markers are usually elevated. Delayed infections, however, may be more difficult to recognize because symptoms are less severe, and they are often caused by less virulent microorganisms such as coagulase-negative staphylococci and other skin organisms.

Management

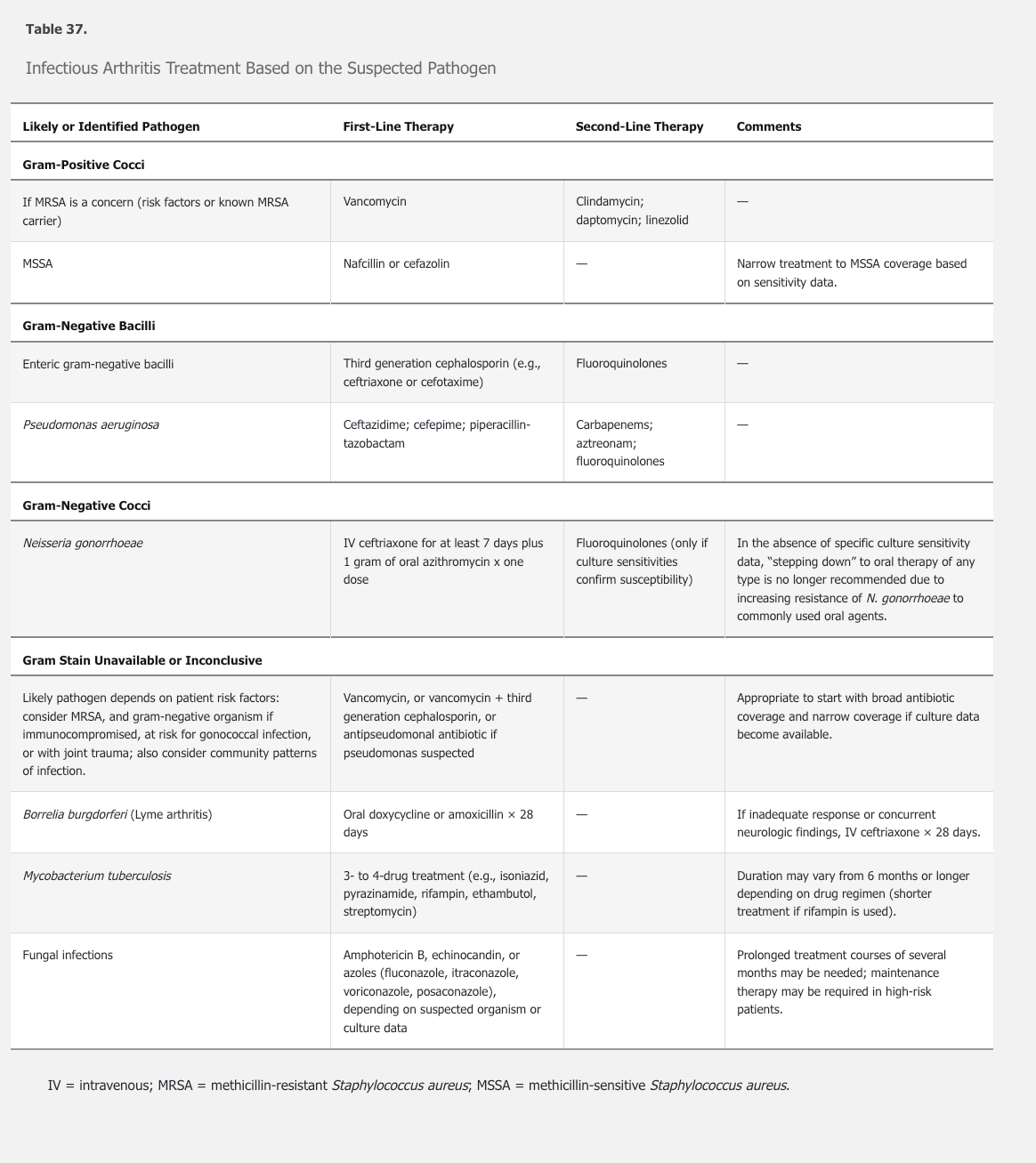

In patients with suspected infectious arthritis, blood and synovial cultures must be obtained before treatment, but empiric antibiotic therapy should be started while awaiting culture results (Table 37). In suspected bacterial arthritis, the initial antimicrobial coverage should be broad and account for host factors such as immunosuppression as well as likely causative microorganisms and regional antibiotic sensitivity data. Antibiotics should initially be given parenterally. Given the high prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus, vancomycin is often initially used to cover gram-positive cocci. The duration of treatment depends on the causative organism and patient response, but usually lasts 2 to 4 weeks.

An infected joint must also be adequately drained. Needle aspiration is an acceptable approach and should be performed regularly (usually daily) as long as there is an effusion. Ultrasound guidance may improve the ability to fully drain the joint. Surgical drainage is an equally good alternative and is more immediately definitive. Additionally, surgical drainage is required for joints that are not easily accessible for needle aspiration (for example, sternoclavicular, sternomanubrial, shoulder, and hip joints), if there is evidence of soft-tissue extension of infection, or if the clinical response to antimicrobial therapy is inadequate. The goal of surgery is to remove all purulent material and nonviable tissue and, in some cases, to perform synovial biopsy or synovectomy.

Antibiotic treatment is recommended for all patients with Lyme arthritis. Approximately 90% of patients will respond to a 28-day course of oral doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime axetil. Patients with incomplete responses may need treatment with a second course or a more aggressive drug regimen, usually intravenous ceftriaxone. Treatment beyond 1 month of ceftriaxone offers no benefit and should not be employed. Antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis occurs in ≤10% of patients, probably represents a progression to sterile autoimmune arthritis, and responds to synovectomy or treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs such as hydroxychloroquine or methotrexate.

Mycobacterial joint infections require at least 6 to 9 months of therapy. Treatment of arthritis associated with viral infections is largely supportive, although specific viral therapy is appropriate for HIV and hepatitis C infection; immunosuppressive therapy with glucocorticoids and rituximab may be needed in refractory hepatitis C–related disease or severe mixed cryoglobulinemia.

Treatment of prosthetic joint infections is challenging and requires early surgical consultation. Orthopedic implants serve as a nidus for microorganisms, and the avascularity of the infected hardware limits antibiotic penetrance. Many patients require removal of the orthopedic device as part of a two-stage procedure, with reimplantation of a new device after an appropriate course of intravenous antibiotics.