Infections in Transplant Recipients

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Introduction

Despite improvements in immunosuppression and antimicrobial therapy, infection remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality after solid organ transplantation (SOT) and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Infection is the most common cause of death in the first year after SOT. Additionally, the interaction of the immune system and infection goes both ways; although immune suppression to prevent rejection increases risk of infection, infection also raises the risk of rejection.

The occurrence of SOT and HSCT procedures continues to increase, as do long-term survival rates owing to improved management of rejection and decreased complications. With more patients living longer after transplantation, awareness of principles involved in the recognition and prevention of infection in transplant recipients remains important for physicians who are not transplant specialists.

Antirejection Drugs in Transplant Recipients

Success after transplantation depends on modulating the immune system to prevent organ rejection in SOT and to minimize graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in allogeneic HSCT. Antirejection regimens involve multiple agents (Table 52) with different mechanisms of action, which are chosen to minimize overlapping toxicities. After SOT, an induction and maintenance strategy is applied; immunosuppression is most intensive in the early period after transplantation and often includes lymphocyte depletion therapy. Immunosuppression may require intensification later for episodes of rejection, and this may again increase the risk of infection.

Glucocorticoids have historically been the cornerstone of antirejection therapy, but steroid-sparing or minimizing regimens are increasingly being used to avoid the toxicities of long-term therapy. Tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or sirolimus are the cornerstones, usually with mycophenolate or, less commonly, azathioprine. Drug interactions are common with these agents, and many drugs can affect antirejection medication levels. Monitoring is important to balance adequate immunosuppression with toxicity.

Posttransplantation Infections

Timeline and Type of Transplant

Infection may occur at any time after transplantation, but periods of highest immunosuppression, usually within the first few months after transplantation, carry the highest likelihood. Risk for infection is also affected by pre-existing conditions (such as diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, or neutropenia) and by colonization with resistant organisms (such as Burkholderia in cystic fibrosis).

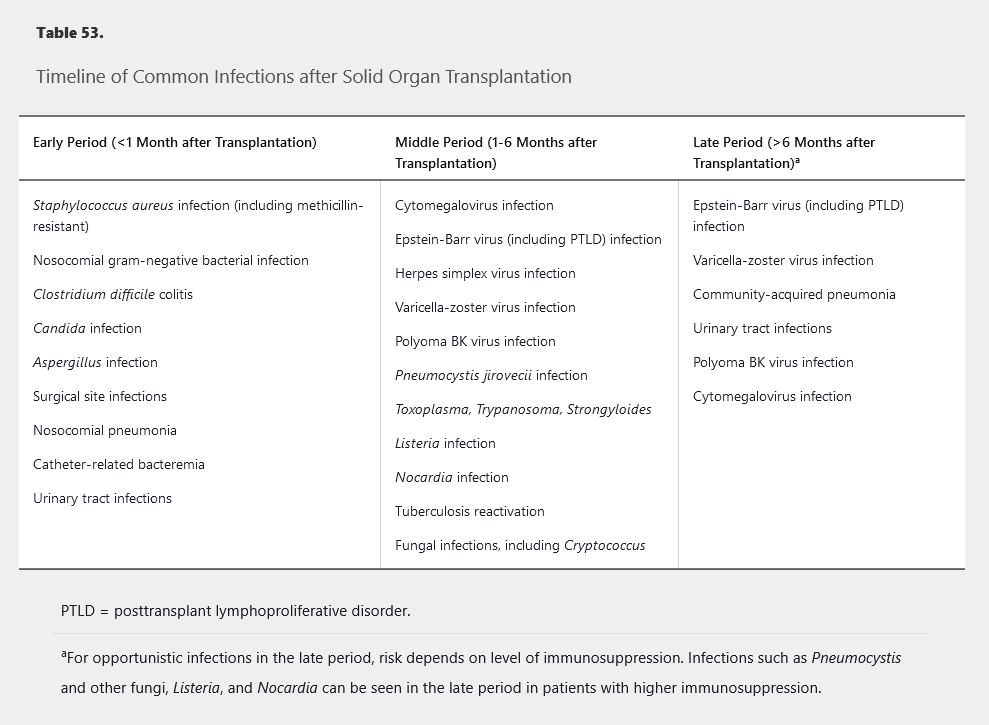

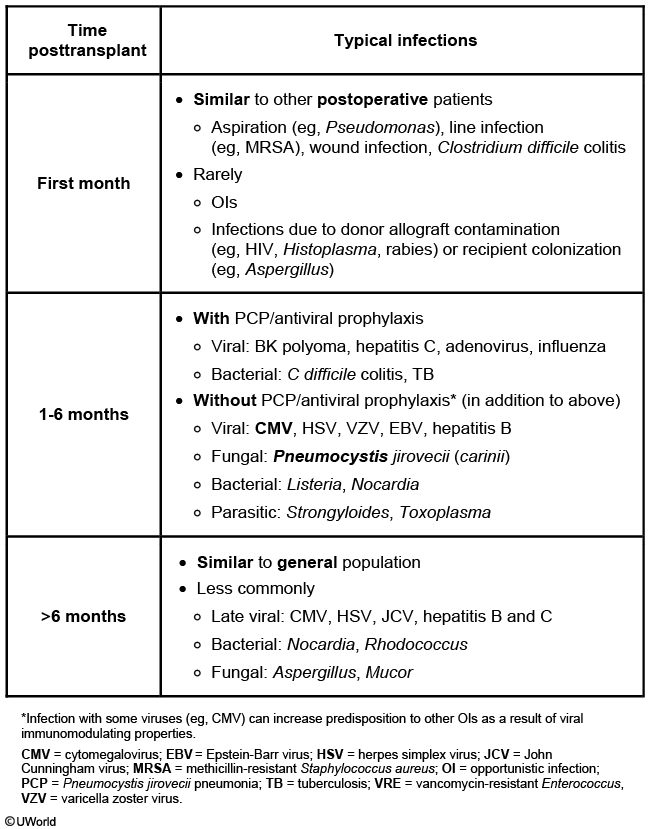

The risk of specific infections varies depending on the time frame after transplantation. Table 53 shows the typical timeline of risk for specific infections after SOT. However, the timeline restarts when treating episodes of rejection, and infection risk in the late period depends on the level of immunosuppression required. Knowledge of the risk timeline and effect of the immunosuppression level can be helpful in recognizing likely infections and in preventing infections through targeted prophylaxis. In the first month after SOT, infections are similar to those seen in other hospitalized postsurgical patients, including a risk of resistant bacteria, and most often involve the lungs, urinary tract, and surgical sites. The middle period usually encompasses the most intensive immunosuppression, with significant risk for viral (such as cytomegalovirus) and fungal (such as Pneumocystis) infections owing to defects in cell-mediated immunity. If immunosuppression can be de-escalated during the late period, risk for opportunistic infections decreases overall, but patients remain at risk for certain viral infections and have increased risk for community-acquired bacterial infections

Additional general considerations include the higher likelihood of infections to disseminate after transplantation and the subtle or atypical presentation of infection because of changed anatomy after transplantation. Immunosuppressive drugs may also contribute to altered presentation because of reduction in fever and other inflammatory responses making the usual signs and symptoms of infection less prominent. Noninfectious complications such as GVHD or malignancy may also be confused with infection. For some infections, the risk strongly depends on donor and recipient characteristics. Standard donor and recipient pretransplantation testing includes serologies for cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; varicella-zoster virus; HIV; hepatitis B, C, and E viruses; syphilis; toxoplasmosis; and Strongyloides, Leishmania, and Trypanosoma if from an endemic area and interferon-γ release assay for latent tuberculosis infection.

Additional general considerations include the higher likelihood of infections to disseminate after transplantation and the subtle or atypical presentation of infection because of changed anatomy after transplantation. Immunosuppressive drugs may also contribute to altered presentation because of reduction in fever and other inflammatory responses making the usual signs and symptoms of infection less prominent. Noninfectious complications such as GVHD or malignancy may also be confused with infection. For some infections, the risk strongly depends on donor and recipient characteristics. Standard donor and recipient pretransplantation testing includes serologies for cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; varicella-zoster virus; HIV; hepatitis B, C, and E viruses; syphilis; toxoplasmosis; and Strongyloides, Leishmania, and Trypanosoma if from an endemic area and interferon-γ release assay for latent tuberculosis infection.

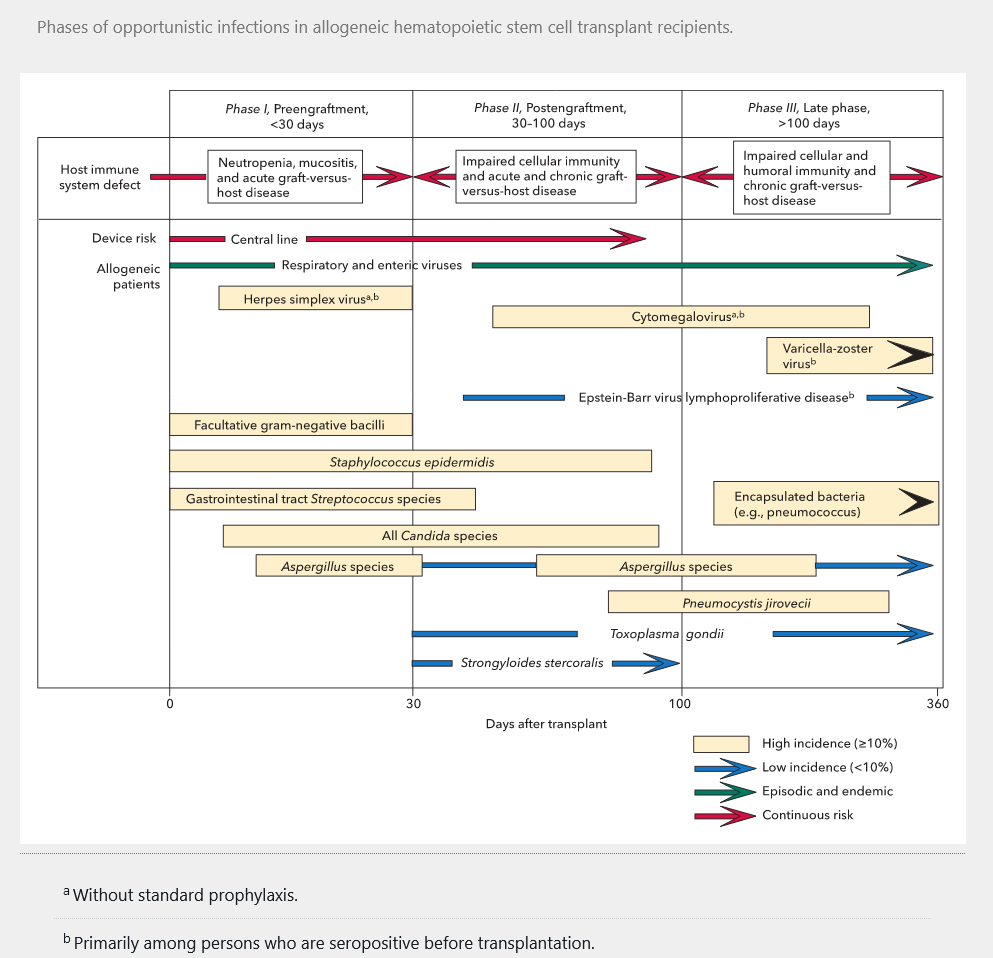

Risk after HSCT is much greater for allogeneic than autologous transplantation because of the myeloablative conditioning regimen. After allogeneic HSCT, patients undergo a prolonged period of intense neutropenia, putting them at risk for bacterial infections, Candida and mold infections, and herpes simplex and other virus reactivation. This is followed by a prolonged period of impaired cell-mediated and humoral immunity because of immunosuppression to reduce GVHD. Development of chronic GVHD can also increase risk for infections caused by immune system effects and breakdowns in mucosal and other barriers. Infections in this later period are similar to those in the later period after SOT. Figure 21 shows the timeline of risk for specific infection after allogeneic HSCT.

Specific Posttransplantation Infections

Viral Infections

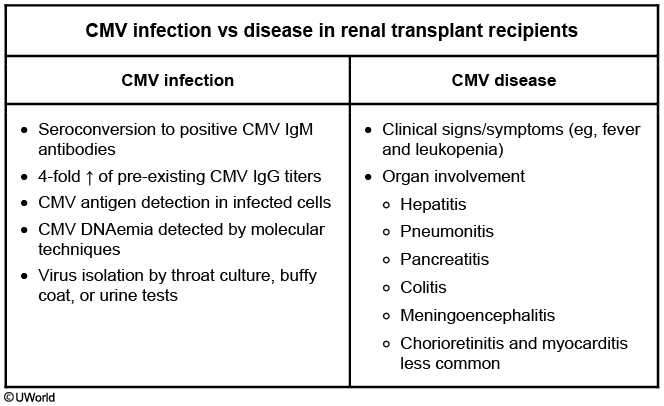

Cytomegalovirus is the most significant viral infection after transplantation, with risk for infection depending on donor and recipient serology. After SOT, the risk for cytomegalovirus is highest (>50%) for donor-positive/recipient-negative, intermediate (15%-20%) for recipient-positive, and lowest for donor-negative/recipient-negative transplantations. Risk is also significantly increased with use of lymphocyte-depleting agents. Comparatively, after allogeneic HSCT, the risk of cytomegalovirus is highest for donor-negative/recipient-positive transplantations. Cytomegalovirus is an immunomodulatory virus, and active cytomegalovirus infection after transplantation is associated with increased rates of rejection and GVHD, as well as increases in other opportunistic infections and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). Cytomegalovirus often presents as a nonspecific viral syndrome with fever and cytopenias. Specific organ disease owing to cytomegalovirus includes pneumonitis (more common in HSCT than SOT) (CMV pneumonia, nonspecific bilateral lung opacity, treat with ganciclovir, encephalitis, hepatitis, and other gastrointestinal sites. Although cytomegalovirus can cause disease anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, colitis is the most common gastrointestinal disease after SOT, whereas esophagitis is more common after HSCT. Definitive diagnosis of organ disease depends on demonstration of cytomegalovirus in biopsy, although presumptive diagnosis can be made based on cytomegalovirus viremia, demonstrated by quantitative nucleic acid amplification testing, in the appropriate clinical setting.

This patient most likely has cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease. CMV infection is defined as detection of CMV antibodies, antigen, DNA, or virus without significant clinical symptoms. CMV disease is usually associated with a rejection episode and increased immunosuppression. Patients typically develop a mononucleosis-like illness with low-grade fever, malaise, leukopenia, and some degree of organ involvement (eg, hepatitis, pancreatitis, colitis, meningoencephalitis, and pneumonitis). CMV eye disease is more common in HIV than organ transplant patients.

CMV disease is more common in CMV-positive donors and CMV-positive recipients. Several strains of cytomegalovirus do not confer cross-immunity. Recipients may have reactivation of existing virus or superinfection with a new donor viral strain. This patient was appropriately treated with valgancicyclovir (preferred prophylactic for CMV) for the first 3 months following transplantation but had organ rejection with a change in immunosuppression. Treatment usually involves immunosuppression reduction and antiviral therapy (eg, ganciclovir) for more severe disease. However, cyclosporine or tacrolimus is not discontinued unless there is life-threatening disease.

Epstein-Barr virus is most significant for its relationship to PTLD resulting from B-cell proliferation; PTLD should be suspected in any patient in the middle or late period presenting with lymphadenopathy or an extranodal mass, often with fever. PTLD risk is higher in patients with a history of pre-existing EBV infection treated with lymphocyte-depleting agents and in those receiving sirolimus and tacrolimus compared with those receiving mycophenolate and cyclosporine. PTLD can range from a benign monoclonal gammopathy to a malignant lymphoma. Treatment of PTLD involves rituximab and decreasing immunosuppression. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus is especially common after HSCT and can be reduced with acyclovir prophylaxis (if the patient is not already receiving an agent for cytomegalovirus). Patients with chronic hepatitis B can have flares of disease if not taking suppressive therapy. Polyoma BK virus can cause a nephropathy in the middle or late period after transplantation.

Bacterial Infections

Bacterial infections are common in the early period after SOT and during neutropenia after HSCT. These are often typical nosocomial infections, including resistant organisms such as methicillin-resistant staphylococci, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms. Clostridium difficile colitis is common, especially with the extensive antibiotic use that accompanies transplantation. Mycobacterium tuberculosis can reactivate with the immunosuppression of transplantation and may present with an atypical pattern on chest radiography or with extrapulmonary disease. Related to persistently low antibody levels, encapsulated organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae remain common even late after HSCT.

Fungal Infections

Fungal infections are most common in the middle period after SOT but may also occur late, especially in the setting of rejection or cytomegalovirus infection. The most common fungal infection without prophylaxis is Pneumocystis pneumonia, which is typically a more aggressive pneumonia in patients after transplantation than in those with AIDS. Cryptococcosis usually presents as subacute meningitis with fever, headache, mental status changes, and lymphocytic pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid, although skin and other organ involvement may also occur; cryptococcal antigen testing is key to diagnosis. Histoplasmosis may also occur in geographically endemic areas and is more likely to present with disseminated disease after transplantation. Mucocutaneous candidiasis is common after SOT and HSCT. Invasive Candida infections and candidemia can be seen, especially in the neutropenic phase after HSCT, as can aspergillosis and other invasive molds, such as Mucor. The risk for invasive fungal infection after HSCT is also increased in later periods by the use of immunosuppressive agents for GVHD. In SOT, pulmonary aspergillosis is most common after lung transplantation.

Protozoa and Helminths

Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan that can reactivate with immunosuppression after transplantation, usually causing encephalitis with fever, headache, and focal neurologic deficits and with multiple ring-enhancing brain lesions on imaging. Strongyloides can cause a hyperinfection syndrome with significant immunosuppression (especially glucocorticoid use), often with secondary pneumonia and gram-negative bacteremia. Reactivation of Trypanosoma or Leishmania can also occur after transplantation, if the recipient or donor were from an endemic area.

Prevention of Infections in Transplant Recipients

Prevention is preferred over treatment strategies for most common infections after transplantation because most opportunistic infections have devastating effects and the cost and toxicity of prophylaxis and immunization are relatively low. Recommended immunizations for SOT and HSCT are shown in Table 54. Most immunizations are safe in patients after transplantation except for live virus vaccines, which should be avoided after transplantation. Close contacts of transplant recipients can receive most routine live vaccines.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is one of the most important prophylactic medications used to prevent Pneumocystis and toxoplasmosis. The duration of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis is determined by the degree of immunosuppression but in most cases is 6 months to 1 year. Prophylaxis may extend longer if immunosuppression cannot be adequately reduced. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be continued lifelong in high-risk cardiac transplantation patients (donor +/recipient -).

Antifungal prophylaxis is indicated during the early months after HSCT and may need to be extended in the setting of GVHD. Coverage should include Candida and Aspergillus, typically with posaconazole or voriconazole.

Patients who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) usually experience a period of prolonged neutropenia after the pretransplant myeloablative conditioning regimen. This prolonged, severe neutropenia is a significant risk factor for invasive bacterial and fungal infections, and prophylaxis for both is indicated. The risk of invasive fungal infection remains elevated, however, even after recovery of neutrophils for the first few months after allogeneic HSCT and even later in the setting of graft-versus-host disease. Therefore, although this patient is doing well and her neutrophil count has recovered, antifungal prophylaxis should be provided in addition to continuing trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy.

Strategies to reduce the effects of cytomegalovirus remain important and include primary prophylaxis, usually with valganciclovir, or regular monitoring for active cytomegalovirus replication by quantitative nucleic acid amplification testing and institution of pre-emptive therapy based on results. Monitoring and pre-emptive therapy is more often used after HSCT, partially because of increased concerns for neutropenia as an adverse effect of prophylaxis and because prophylaxis was not found to be superior to pre-emptive therapy in a randomized controlled trial. The potential role of letermovir, a new antiviral agent without the hematologic toxicity of ganciclovir, is being studied for cytomegalovirus prophylaxis. For SOT, prophylaxis with valganciclovir is preferred for patients at high risk (donor-positive/recipient-negative, those receiving lymphocyte-depleting agents, lung transplants) and is usually given for at least 3 to 6 months.