IBS

- related: GI

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

IBS represents a heterogeneous group of functional bowel disorders defined by the presence of abdominal pain in association with defecation and/or a change in bowel habits. Abdominal pain may worsen or subside with defecation. The altered bowel habits may include constipation, diarrhea, or a mix of both types. Other commonly reported symptoms include abdominal bloating and abdominal distention. The exact cause of IBS remains unknown, and there are no all-encompassing pathophysiologic mechanisms to explain the symptoms. IBS is more common in women and adults younger than age 50 years, and is frequently seen in association with psychosocial disturbance. There are no specific anatomic or physiologic abnormalities, nor are there any reliable biomarkers to define IBS. The diagnosis of IBS requires symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain at least 1 day a week for a period of 3 months, along with at least two of the following three additional criteria: pain related to defecation, change in stool frequency, or change in stool consistency. IBS can then be further subtyped into IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C), IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with mixed bowel habits, or IBS unclassified.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of IBS is no longer one of exclusion; instead, the diagnosis can reliably be made by clinical criteria in the absence of alarm features. Therefore, evaluation for IBS relies on a comprehensive history and physical examination. Fecal calprotectin testing to assess for inflammatory bowel disease and testing for giardiasis and celiac disease should also be considered in patients with chronic diarrhea.

Management

Management of IBS includes lifestyle and dietary modifications, and reassurance that the disease is benign. The focus is control of symptoms. There is limited evidence to suggest that exercise, stress management, and correction of impaired sleep can alleviate the symptoms of IBS.

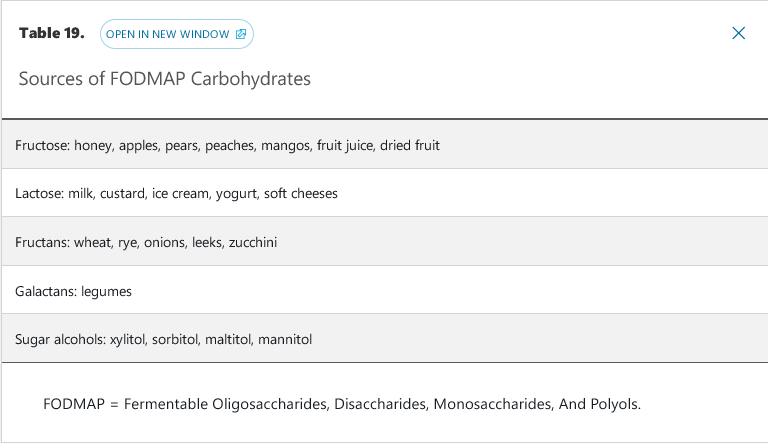

The most common dietary intervention is an increase in fiber, either through diet or use of fiber supplements. Water-soluble fiber supplements such as psyllium are more effective than insoluble dietary fiber such as bran. Dietary restrictions can include avoidance of trigger foods, gluten (in the absence of celiac disease), dairy products, and FODMAPs (see Table 19). Randomized trials have shown that a low-FODMAP diet alleviates symptoms in patients with IBS. When these initial measures fail to relieve symptoms, medications, typically directed at the primary symptoms of IBS such constipation, diarrhea, or abdominal pain, are employed. The evidence supporting the use of the various agents is variable, with few rigorous studies showing long-term effectiveness.

Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Predominant Constipation

Several peripherally acting medications have demonstrated efficacy and safety in the treatment of IBS-C (see Table 22). The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has given a strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence for the use of linaclotide, followed by a conditional recommendation for the use of lubiprostone based on moderate-quality evidence and a conditional recommendation for the use of polyethylene glycol based on low-quality evidence in the treatment of IBS-C. Probiotics have uncertain benefit and should be used in the context of a clinical trial.

Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Predominant Diarrhea

Prescription medications with FDA approval for the treatment of IBS–D include rifaximin, eluxadoline, and alosetron. A 14-day course of rifaximin has shown superiority to placebo in relieving the global symptoms, bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stools associated with IBS-D for up to 10 weeks after treatment. A retreatment study of patients with recurring IBS-D symptoms after an initial course of rifaximin showed that a second 14-day treatment of rifaximin was superior to placebo in relieving abdominal pain and improving stool frequency for 4 weeks after treatment.

Eluxadoline (combination of a µ-opioid receptor agonist and a δ-opioid receptor antagonist) was superior to placebo in the treatment of men and women with IBS-D for up to 26 weeks based on a composite response of decreased abdominal pain and improved stool consistency in two randomized trials. Use of eluxadoline is contraindicated in patients without a gallbladder and in those with known or suspected biliary obstruction, Sphincter of Oddi disease or dysfunction, ingestion of three or more alcoholic beverages a day, history of pancreatitis or structural disease of the pancreas, severe hepatic impairment, or history of severe constipation.

Alosetron (a selective 5-HT3 antagonist) has alleviated abdominal pain and the global symptoms of women with IBS-D in pooled data from several randomized trials. The AGA has given it a conditional recommendation for the treatment of women with IBS-D based on moderate-quality evidence. Due to the risk for severe constipation and ischemic colitis, prescribers must be enrolled in an FDA-mandated risk evaluation and mitigation strategy program in order to prescribe alosetron.

Other medications with clinical evidence for the treatment of IBS-D include loperamide, antispasmodics, and tricyclic antidepressants. The AGA has given a conditional recommendation for loperamide use in patients with IBS-D. Although loperamide has not demonstrated global relief of IBS-D symptoms, this recommendation is based on its ability to reduce stool frequency in other diarrheal conditions, as well as its low cost, favorable safety profile, and wide availability. Antispasmodics (for example, cimetropium-dicyclomine, peppermint oil, pinaverium, and trimebutine) decreased abdominal pain and global symptoms of IBS in a meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials. Although the overall quality of studies was low, the AGA gave a conditional recommendation for the use of antispasmodics in IBS-D. Based on data from several randomized trials, tricyclic antidepressants offer modest relief of the abdominal pain and global symptoms of IBS-D. The AGA has given a conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence for the use of tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of IBS-D.

Management of Patients with Indeterminate Abdominal Pain

When abdominal pain is the primary symptom and is unrelated to food intake and defecation, centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome (CAPS) should be considered. Abdominal pain is described as constant, nearly constant, or frequently recurring. The pain is not localized and may include extraintestinal symptoms such as musculoskeletal pain. It can be associated with impairment in activities of daily living and psychosocial issues. CAPS is a result of central sensitization with disinhibition of pain signals. Limited evaluation is needed in the setting of chronic pain meeting the diagnostic criteria for CAPS. Initial evaluation should include a detailed medical and psychosocial history, physical examination, and limited laboratory studies to exclude gastrointestinal bleeding and inflammation.

Successful treatment depends on the patient-physician relationship, and should focus on setting appropriate goals and expectations. A combination of pharmacologic and/or psychological therapies may be needed, including tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Four classes of psychotherapy have shown benefits in CAPS when combined with medical therapy: cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy, mindfulness- and acceptance-based therapy, and hypnotherapy.

Narcotic bowel syndrome, also known as opiate-induced gastrointestinal hyperalgesia, is characterized by the paradoxical increase in abdominal pain with increasing doses of narcotics despite clinical evidence showing improvement or stability of the underlying condition. Often these patients fear tapering off narcotics and believe the narcotics are “the only thing that helps.” The only treatment is complete detoxification and cessation of narcotic use, which requires a trusting patient-physician relationship and understanding of the pathophysiology of the pain. Enrollment in a supervised detoxification program is recommended.