Health Care–Associated Infections

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Epidemiology

Health care–associated infections (HCAI) have been linked to indwelling medical devices, prosthetic devices and materials, surgery, invasive procedures, transmission of organisms between patients and health care personnel, and environmental factors. Four percent of hospitalized patients acquire at least one HCAI, costing the U.S. health care system an estimated $28 billion to $45 billion annually. HCAIs include pneumonia and surgical site infections (21.8% each), gastrointestinal infections (17.1%), urinary tract infections (12.9%; 67.7% associated with catheters), and primary bloodstream infection (9.9%; 84% associated with central venous catheters).

Elimination of HCAIs remains important for the U.S. health care system. Sixty-five percent to 70% of catheter-associated bloodstream and urinary tract infections and 55% of ventilator-associated pneumonias and surgical site infections are preventable. Progress toward elimination varies by type of infection. Central line–associated bloodstream infections decreased by 50% and surgical site infections by 17% between 2008 and 2014; rates of catheter-associated urinary tract infections showed little change between 2009 and 2014.

Prevention

Hand hygiene is the foundation of infection prevention, but adherence has been reported as less than 50%. Most facilities have improved in the last decade, with some facilities showing sustained improvement to 90% adherence. Hand hygiene should be performed at least before and after every patient contact. The World Health Organization's five key hand hygiene moments are commonly used to define hand hygiene opportunities: before touching a patient, before clean or aseptic procedures, after body fluid exposure risk, after touching a patient, and after touching patient surroundings. Hand hygiene should include all surfaces of the hands up to the wrists, between fingers, and the fingertips. Alcohol-based hand rubs are generally preferred to soap and water hand disinfection, except when hands are visibly soiled, when personnel come in direct contact with blood or body fluids, or after contact with a patient with Clostridium difficile infection or his or her environment.

Standard precautions should be practiced for every patient to protect health care personnel from exposure to bloodborne pathogens. Blood and all body fluids except sweat are potentially infectious, regardless of the patient's presumed or known infection status. Personal protective equipment (gloves, gown, mask, and eye protection) are barriers protecting health care personnel from exposure to blood and body fluids. Protective equipment should be removed in the following order: 1) gloves, careful not to contaminate hands; 2) goggles/face shields; 3) gown, pull away from neck and shoulders, turn inside out to discard; 4) mask/respirator by grasping bottom then top ties/elastic. This process should be followed by hand hygiene. Transmission-based precautions (airborne, contact, droplet) are performed in addition to standard precautions to prevent transmission of epidemiologically significant organisms (Table 55).

Additional preventive measures include careful and judicious device use, safe injection practices (one needle, one syringe, only one time), aseptic technique for invasive procedures and surgery, and a clean environment and patient equipment. HCAI prevention “bundles” comprise three to five evidence-based processes of care that, when performed together, consistently have a greater impact on decreasing HCAIs than individual components performed inconsistently.

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are the most common device-associated HCAI, and 17% to 69% may be preventable. Urinary catheters are used in 15% to 25% of hospitalized patients in the United States, compelling efforts to establish appropriateness criteria for catheter use. Adverse outcomes related to CAUTI include pyelonephritis, perinephric abscess, and bacteremia (<5%). Escherichia coli is the most common CAUTI pathogen, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae/Klebsiella oxytoca, Candida species, and Enterococcus species; antibiotic resistance among these pathogens is increasing.

Duration of catheterization is the primary modifiable risk factor for CAUTI; each day of catheterization increases the risk of CAUTI. Nonadherence to aseptic technique (for example, opening a closed system) and insertion by a less experienced operator also increase the risk. Other risk factors for CAUTI include female sex, age older than 50 years, diabetes mellitus, severe or nonsurgical underlying illness, and serum creatinine level greater than 2.0 mg/dL (176.8 µmol/L). Appropriate indications for indwelling urinary catheters are listed in Table 56. Management of urinary incontinence using external catheters is preferred when feasible. Provision of care in the ICU is not itself an indication for a catheter.

Diagnosis

Patients with an indwelling urethral or suprapubic catheter (or catheter removed in the 48 hours before symptom onset) or using intermittent catheterization who have signs and symptoms compatible with urinary tract infection (UTI; see Urinary Tract Infections for information), no other identifiable infection source, and ≥103 colony-forming units/mL of one or more bacterial species in a urine specimen are diagnosed with a CAUTI. Catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria (≥103 colony-forming units/mL without urinary tract signs or symptoms) is common and generally does not require treatment.

Treatment

A urinalysis and urine culture should always be obtained before initiating antimicrobial treatment to determine if antimicrobial resistance is present and to guide definitive therapy. CAUTI management includes removing the urinary catheter (and only replacing if still needed). Removal is strongly recommended for catheters in place for 2 or more weeks because biofilm on the catheter makes it difficult to eradicate bacteriuria or funguria and may lead to antimicrobial resistance. Therapy should always be adjusted to the narrowest coverage spectrum possible based on culture results. Treatment is given for 7 days if symptoms resolve promptly and longer (10-14 days) for patients with delayed response. Candiduria in a patient with a catheter almost always represents colonization and rarely requires treatment. Candida CAUTI is considered when significant candiduria persists despite catheter removal or replacement and the patient is symptomatic. CAUTIs caused by Candida species requiring treatment should be treated for 14 days.

Prevention

Key prevention strategies include appropriately limiting urinary catheter use (see Table 56) and considering other options associated with lower infection risk (intermittent straight catheterization, external catheters) when urine collection is necessary (Table 57). Most studies have not shown definitive benefit of antimicrobial- or antiseptic-coated catheters for short- (<14 days) or long-term catheterization; these catheters are more expensive and, in some cases (such as nitrofurazone-coated catheters), cause more patient discomfort.

Surgical Site Infections

Surgical site infections (SSIs) account for 23% of HCAIs. The overall risk of developing an SSI after surgery is 1.9%. Wound class affects the risk of infection, with clean wounds having less than a 2% risk of infection, clean contaminated wounds having less than a 10% risk, and contaminated wounds having a 20% risk. Most infections occur within 30 days after surgery or within 90 days after surgery with implants; however, infections can manifest beyond these ranges. Risk factors include patient-related, procedure-related, and postoperative factors (Table 58). The patient's skin and gastrointestinal or female genital tracts are major sources of organisms causing infection, depending on the type of surgery. The time during which the surgical site is open represents the period of greatest risk. Common SSI pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus (23%), coagulase-negative staphylococci (17%), enterococci (7%), Escherichia coli (5%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5%). Exogenous sources of organisms (surgical personnel, surgical instruments, environment) are less common causes of SSIs, usually identified when a cluster of infections is present.

S. aureus is the most common pathogen (23%) associated with surgical site infections (SSIs). SSIs after coronary artery bypass graft surgery can be serious and devastating, with mediastinitis related to S. aureus of particular concern. The 2016 World Health Organization guidelines recommend that patients known to be nasal carriers of S. aureus who are scheduled to undergo cardiothoracic or orthopedic surgery should have preoperative decolonization (mupirocin ointment for 5 days with or without chlorhexidine gluconate body wash) to decrease the risk of developing S. aureus–related SSI.

Diagnosis

Clinical signs and symptoms vary by site and type of infection as well as by implicated organism (for example, some are more likely to cause purulence). Inflammatory changes at the surgical site (pain or tenderness, warmth, swelling, erythema) and purulent drainage suggest a superficial incisional infection. Deep incisional SSIs have more extensive tenderness expanding outside the area of erythema and more systemic signs, such as fever and leukocytosis. Wound dehiscence suggests a deep incisional SSI unless the wound or drainage is culture negative. Organ and deep-space SSIs are associated with more systemic signs and local symptoms related to a deep abscess or infected fluid collection. In cases of suspected organ or deep-space SSIs, CT is helpful to localize the infection and determine the best approach to drainage of the fluid or abscess for culture and treatment. When an SSI is suspected, drainage, purulent fluid, and infected tissue should be obtained for culture. Deep-tissue or wound cultures are preferable to superficial wound swab cultures that are likely to reflect skin or wound colonization and not necessarily yield the causative pathogen.

Treatment

SSI treatment requires debridement of necrotic tissue, drainage of abscesses or infected fluid, and specific antimicrobial therapy for organ or deep-space and deep incisional infections. Repeat debridement or drainage may be required to control and resolve the infection even with appropriate antimicrobial therapy. When an SSI involves an implant, removal of the implant is preferred, followed by a prolonged course of antibiotics (6-8 weeks). Superficial incisional infections can usually be managed with oral antibiotics without tissue debridement. The choice of antimicrobial agent is guided by culture results; duration of treatment varies by anatomic site and by depth of infection.

Prevention

Prevention is divided into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures (see Table 58). Modifiable host factors should be optimized before surgery. If antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated, select the correct agent, dose, and time for administration (60 minutes before incision, 2 hours before incision for vancomycin or fluoroquinolones), and redose during surgery based on surgery duration and antibiotic half-life. Continuing antibiotics postoperatively does not decrease SSI incidence, even in cases of intraoperative spillage of gastrointestinal contents or presence of wound drains.

Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections

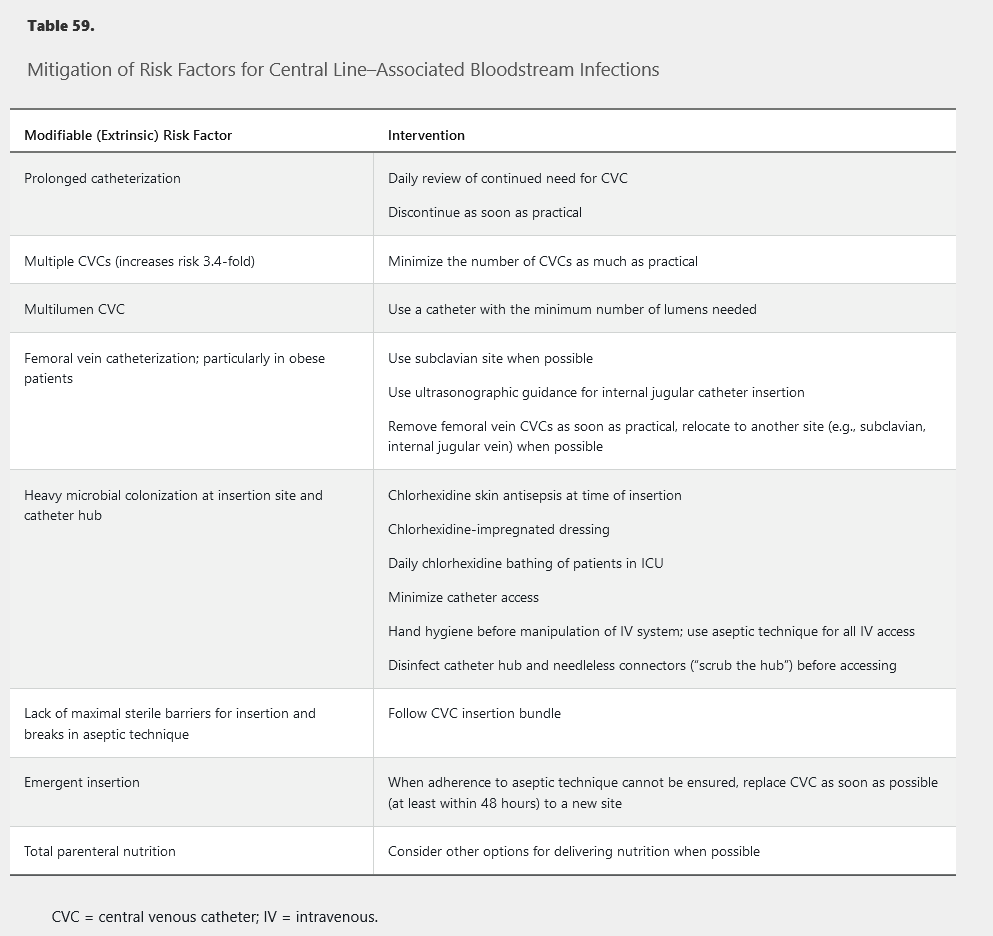

Central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), associated with all types of central venous catheters (CVCs), are the most preventable HCAI. In the United States, CVC rates are 55% in ICU patients and 24% in non-ICU patients. Pathogens associated with CLABSIs include coagulase-negative staphylococci (20.5%), S. aureus (12.3%), Enterococcus faecalis (8.8%), non-albicans Candida species (8.1%), Klebsiella pneumoniae or oxytoca (7.9%), Enterococcus faecium (7%), and Candida albicans (6.5%). Antimicrobial resistance is a problem for many of these pathogens. CLABSI risk factors include prolonged hospitalization before catheterization, neutropenia, and reduced nurse-to-patient ratio in the ICU. Additional risk factors (modifiable) are shown in Table 59.

Diagnosis

CLABSI is suspected when a patient with a CVC has bacteremia not resulting from infection at another site. Two sets of peripheral blood cultures (20 mL blood/set) should be obtained from different sites before starting antibiotics. Blood cultures drawn directly from CVCs have a higher rate of false positivity and should be avoided; they may falsely identify a CLABSI and lead to unnecessary antibiotic therapy.

Treatment

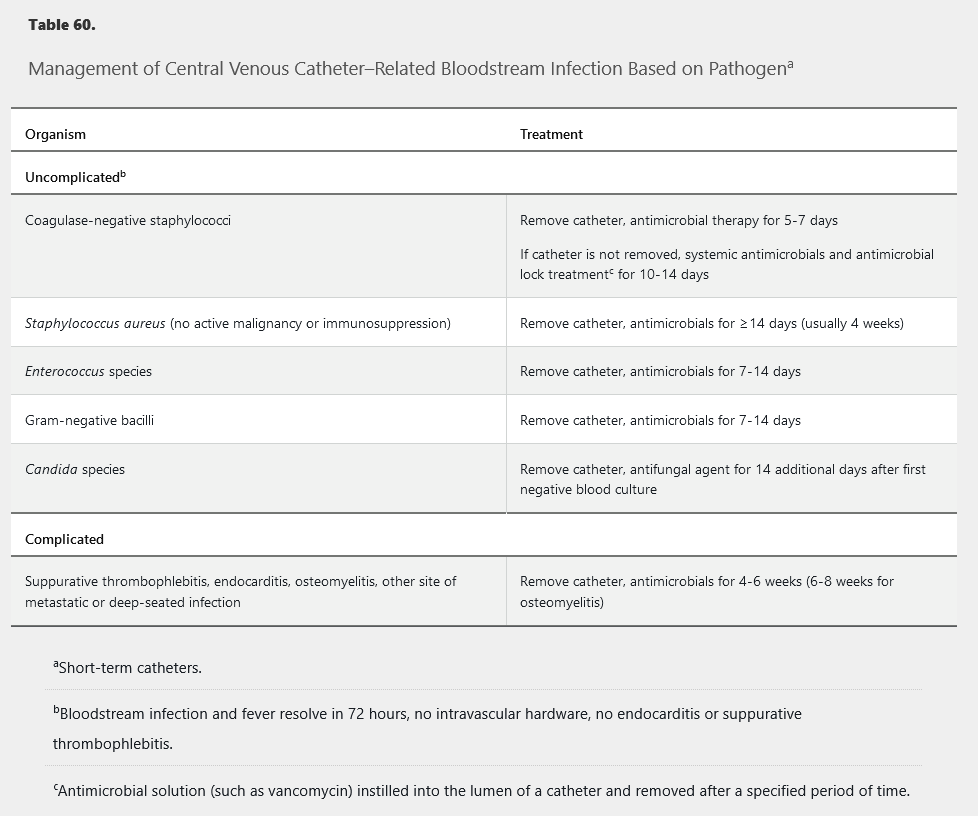

Infected CVCs should be removed. CVC removal is particularly important for S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Candida species infections. The duration of therapy for most cases of uncomplicated non–S. aureus CLABSI is 7 to 14 days (Table 60). S. aureus CLABSI is usually treated for at least 4 weeks; however, shorter-term therapy may be considered in select patients who have immediate catheter removal with resolution of fever and bacteremia within 72 hours of starting appropriate therapy and who have no implanted prosthetic devices, no evidence of endocarditis by echocardiography (preferably transesophageal), no evidence of suppurative thrombophlebitis, no evidence of metastatic infection, and neither diabetes mellitus nor immunosuppression. Bacteremia clearance should be confirmed with follow-up blood cultures. If bacteremia persists after CVC removal and appropriate antimicrobial therapy, evaluation for a deeper source of infection, including endocarditis, should be performed. All patients with candidemia should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist to rule out the presence of candida endophthalmitis within 1 to 2 weeks.

Prevention

CVCs should be inserted only by experienced personnel using the insertion bundle of hand hygiene, chlorhexidine skin antisepsis of the insertion site using recommended application methods and contact time, maximal barrier precautions (mask, cap, gown, sterile gloves, large sterile drape covering patient), and optimal catheter site selection (subclavian site preferred, avoid femoral site). See Table 59 for further modifiable factors to prevent CLABSI. Insertion bundles, checklists, and staff education have significantly reduced CLABSIs. If CLABSI rates remain high despite adherence to these strategies, patient chlorhexidine bathing and antimicrobial-impregnated catheters (silver-sulfadiazine–chlorhexidine, minocycline-rifampin) may be considered. Routine CVC exchange or replacement or administration of systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis at time of insertion or during CVC use should be avoided.

Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia

S. aureus is a leading cause of hospital-acquired bacteremia. Endocarditis and vertebral osteomyelitis are two important complications of S. aureus bacteremia, although they are less likely when the infection is hospital acquired. The source of bacteremia and possible metastatic infection should be determined, starting with a detailed history and examination. All patients should undergo evaluation for endocarditis with echocardiography, preferably transesophageal. Source control with removal or drainage of any focus of infection is important for treatment success. Blood cultures should be repeated every 2 to 4 days until results are negative to document clearance.

Bacteremia caused by methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) should be treated with a penicillinase-resistant semisynthetic penicillin (such as oxacillin) or first-generation cephalosporin (such as cefazolin) at maximal doses. Vancomycin should be avoided in patients with MSSA who are not allergic to β-lactam antibiotics. Vancomycin is associated with higher rates of relapse and microbiologic failure in the treatment of MSSA bacteremia.

For methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) bacteremia, vancomycin and daptomycin are the preferred antibiotics. Based on efficacy and safety data, vancomycin trough monitoring is no longer recommended and should be replaced with the 24-hour time-concentration area under the curve (AUC) guided dosing. AUC-guided dosing requires pharmacist consultation and an AUC calculator. Patients with concomitant S. aureus pneumonia should not receive daptomycin because it is inactivated by surfactant. The clinical and microbiologic response (clearance of bacteremia) determines whether to continue vancomycin or change to daptomycin when the MRSA isolate has a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration of ≤2 µg/mL. Persistent bacteremia may be the result of slow bactericidal activity of vancomycin, inadequate dosing, poor tissue penetration, or inadequate source control. Higher-dose daptomycin (8-10 mg/kg/d) is sometimes used if bacteremia persists despite adequate source control. Vancomycin should not be used when the isolate has a minimum inhibitory concentration greater than 2 µg/mL; daptomycin is an acceptable alternative if the isolate is susceptible. The median time to clearance of MRSA bacteremia is 7 to 9 days.

Bacteremia that persists beyond 72 hours of starting appropriate antibiotic treatment suggests a complicated S. aureus infection and requires additional evaluation and a longer course of antibiotics (4-6 weeks). Management of persistent MSSA and MRSA bacteremia also includes a thorough search for and removal of all foci of infection, including surgical debridement of infected wounds and abscess drainage. A new focus of infection may develop with persistent bacteremia and should always be considered in the evaluation of persistent bacteremia. Combination antimicrobial agents (for example, a β-lactam and aminoglycoside, vancomycin and rifampin) have not been shown to improve outcomes and should not be used.

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia and Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is pneumonia developing more than 48 hours after hospitalization. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is pneumonia developing 48 hours after endotracheal intubation; it occurs in 10% of patients undergoing ventilation. Half of patients with HAP develop serious complications, including respiratory failure, pleural effusion, septic shock, empyema, and kidney injury. Mechanical ventilation increases the risk of pneumonia 6-fold to 21-fold. HAP and VAP risk factors include age older than 70 years, recent abdominal or thoracic surgery, immunosuppression, and underlying chronic lung disease. Modifiable risk factors are listed in Table 61.

HAP and VAP are most commonly caused by bacteria, but viral and fungal pathogens should be considered in immunocompromised patients. The main risk factor for MRSA, antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas, or other antibiotic-resistant pathogens is intravenous antibiotic use within the past 90 days. Additional risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens associated with VAP are septic shock at the time of VAP, acute respiratory distress syndrome preceding VAP, 5 or more days of hospitalization before VAP, and acute kidney replacement therapy before VAP.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical, radiographic, and microbiologic findings. A new lung infiltrate on imaging plus clinical findings, including new-onset fever (temperature >38 °C, 100.4 °F), leukocytosis or leukopenia, purulent sputum, and decline in oxygenation, suggest pneumonia. Noninvasive sampling (endotracheal aspiration) with semiquantitative sputum cultures (heavy, moderate, light, and no growth) are suggested for diagnosing VAP. Clinical findings without radiographic support suggest tracheobronchitis, which does not require antibiotic treatment.

Treatment

Therapy for suspected HAP should be based on respiratory sample culture results; a specimen from the lower respiratory tract should be obtained before starting antimicrobial therapy. However, inability to obtain a specimen should not delay therapy initiation for VAP, and empiric antimicrobial therapy should be instituted for patients with VAP pending results of noninvasive sampling with semiquantitative cultures and based on local VAP antibiograms, if available.

Empiric VAP regimens should include coverage for S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli. An agent active against MRSA (vancomycin, linezolid) should be included for patients with MRSA risk factors or those in a unit with MRSA prevalence greater than 10% to 20% or unknown. Two antipseudomonal agents of different classes are recommended for empiric regimens only for patients with risk factors for resistance, with structural lung disease (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis), or in a unit with greater than 10% resistance to an agent being considered for monotherapy. Similar regimens are recommended for patients with HAP who are treated empirically. Antimicrobial coverage for oral anaerobes may be considered in patients with witnessed aspiration events or recent surgery. Cephalosporins should be avoided as monotherapy in settings where extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)–producing gram-negative organisms (such as Klebsiella pneumoniae) are prevalent; consider a carbapenem instead. VAP caused by gram-negative organisms sensitive only to aminoglycosides or colistin may be treated with a combination of systemic and aerosolized antibiotics.

Microbiologic results should be reviewed at 48 to 72 hours, and all patients should be re-evaluated for clinical improvement. Antimicrobial therapy should be de-escalated (to narrow-spectrum or oral therapy) based on microbiologic results and clinical stabilization or discontinued if the diagnosis of pneumonia is in doubt. Patients who do not improve within 72 hours of appropriate therapy should undergo investigation for infectious complications, an alternate diagnosis, or another site of infection. HAP and VAP should be treated for 7 days or less.

Prevention

Commonly used ventilator bundles include subglottic suctioning, peptic ulcer disease and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, and avoiding gastric overdistention. Use of ventilator bundles has been shown to decrease VAP rates by 71%. Additional interventions are listed in Table 61.

Hospital-Acquired Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Organisms

Antimicrobial resistance has been noted in nearly all bacterial pathogens. Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are most prevalent in health care settings (highest incidence in long-term acute care hospitals) but are also observed in the community. Seven of the 15 MDROs deemed urgent threats are predominantly health care associated. Nearly half of S. aureus HCAIs in the United States are methicillin resistant, 30% of enterococci are vancomycin resistant, 18% of Enterobacteriaceae produce ESBL and are resistant to all β-lactam antibiotics, 4% of Enterobacteriaceae are resistant to carbapenems, and 16% of P. aeruginosa and about half of Acinetobacter species are multidrug resistant. Clostridium difficile is not technically an MDRO, but it is a problematic pathogen in health care settings.

MDRO infections are difficult to treat, with mortality rates up to four times higher than infections caused by antibiotic-sensitive strains. Limiting transmission of MDROs in health care settings requires full adherence to hand hygiene protocols, contact precautions, and cleaning and disinfecting of the environment and patient care equipment. More than half of hospitalized patients receive antibiotics, a major risk for acquiring an antibiotic-resistant organism and C. difficile infection. Judicious use of antimicrobial agents is increasingly important to combat the rise of MDROs and emergence of untreatable infections.