Headache and Facial Pain

- related: Neurology

- tags: #neurology

Approach to the Patient with Headache

Formal classification of headache disorders identifies three headache subtypes: primary headaches, secondary headaches, and painful cranial neuralgias. Primary headaches, or those in which the symptoms are due to a specific headache disorder, are more commonly seen in practice and are defined by clinical criteria. Primary headache disorders include migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, and the other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Secondary headaches result from another underlying process and are defined by that causative disease process (Table 1); these headaches may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality and require early identification. Patients with serious secondary headaches typically have acute or subacute symptoms and a headache pattern that is progressive or unstable; suspicion of a secondary headache is heightened in the presence of the following clinical “red flags”:

First or worst headache

- Abrupt-onset or thunderclap attack

- Progression or fundamental change in headache pattern

- Neurologic deficit

- New headache in persons older than 50 years

- New headache in patients with malignancy, coagulopathy, immunosuppression, or pregnancy

- Headache triggered by position, exertion, sexual activity, or Valsalva maneuver

A detailed headache history (Table 2) is the most valuable clinical assessment tool in the evaluation of headaches. Neurologic examination with funduscopic testing is essential, and brain imaging is the most important diagnostic study. Brain MRI with contrast is indicated for some of the uncommon primary syndromes (such as trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias). For thunderclap headache, CT imaging of the head without contrast is most appropriate. For a new headache with optic disc edema, or headaches with clinical “red flags,” brain MRI with or without contrast or CT without contrast is usually appropriate. For chronic headaches with new or progressive features, brain MRI with contrast is appropriate. Stable headaches meeting criteria for most primary headaches usually do not require imaging. Additional testing is determined by differential diagnostic considerations and may include erythrocyte sedimentation rate determination, C-reactive protein measurement, lumbar puncture, serum chemistries, or toxicology screens. There is no indication for electroencephalography in the assessment of headache disorders.

Key Points

- Early identification of secondary headaches is essential because of their potentially significant morbidity and mortality; patients with serious secondary headaches typically have acute or subacute symptoms and a headache pattern that is progressive or unstable.

- Stable headaches meeting criteria for most primary headaches usually do not require imaging.

Secondary Headache

Thunderclap Headache

Related Questions

- Question 10

- Question 36

Thunderclap headache is defined as a severe attack of headache pain developing abruptly and reaching maximum intensity within 1 minute. Although occasionally of primary origin, thunderclap headache is a medical emergency that warrants immediate diagnostic evaluation. Noncontrast head CT should be performed without delay. Lumbar puncture with measurement of opening pressure, cell counts, and xanthochromia should be performed if the head CT is nondiagnostic. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI and noninvasive vascular imaging (magnetic resonance angiography [MRA] or CT angiography [CTA]) of cranial and cervical vessels should be performed in patients with a normal CT scan and normal results of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. Table 3 lists essential considerations in the differential diagnosis.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), the most common cause of thunderclap headache, is discovered in nearly 25% of affected patients. The headache associated with SAH may be described as the worst the patient has ever experienced, although the specificity of this finding is limited. Mortality is 50%, with an additional 25% of affected patients experiencing significant morbidity. In the presence of a normal neurologic examination, the following features increase the likelihood of a diagnosis of SAH: age 40 years or older, onset during exertion, witnessed loss of consciousness, or concomitant neck pain. Estimates vary widely, but many patients describe a past headache consistent with a sentinel leak within the previous 1 to 2 weeks; these leaks typically involve abrupt, severe, transient headaches that may be focal or global. Sensitivity of head CT is approximately 95% at 12 hours but decreases to 50% at 1 week. Lumbar puncture in SAH typically reveals a CSF erythrocyte count greater than 10,000/μL (10,000 × 106/L) and an elevation in protein level. CSF xanthochromia may take 4 hours or more to develop but is nearly 100% sensitive between 12 hours and 7 days. Urgent neurosurgical consultation is required.

Headache is the most common symptom and may be the only presenting manifestation with thrombosis of the intracranial veins and sinuses. The pain is typically of sudden onset and is unremitting. Clinical symptoms may be related to the resulting increase in intracranial pressure and include pain exacerbation with the Valsalva maneuver, pulsatile tinnitus, and diplopia. Nonspecific findings of increased intracranial pressure include papilledema, decreased mentation, and seizures. Abducens nerve (cranial nerve VI) palsy secondary to increased intracranial pressure may falsely indicate a focal lesion (falsely localizing abducens nerve palsy). Specific findings may help localize the thrombosis. Cavernous sinus thrombosis usually involves extension of dental or sinus bacterial infection and manifests as acute-onset headache, proptosis, periorbital edema, and ophthalmoplegia; this disorder requires immediate administration of antibiotics, often with surgical drainage. Other forms of cerebral venous thrombosis are not related to infection and often occur in the presence of hypercoagulable states, thrombophilia, pregnancy (and the puerperium), oral contraceptive use, or dehydration. Anticoagulation is recommended even in those patients with hemorrhagic parenchymal lesions. Treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin results in lower hospital mortality than treatment with unfractionated heparin. Anticoagulation with warfarin is generally continued for a minimum of 3 to 6 months. Extended anticoagulation should be considered in those with severe hypercoagulable states, myeloproliferative disorders, or recurrence and perhaps in those with idiopathic thrombosis.

Dissections of the cervical vessels (Figure 1) often present with acute pain in the head and neck, typically occur in younger patients, and may develop spontaneously or as a result of trauma, which may be minor. Risk factors include hypertension, migraine, polycystic kidney disease, and connective tissue disorders. Extracranial dissections are a common cause of stroke in persons younger than 50 years. Dissections of the carotid artery often present with orbital pain, partial Horner syndrome (ptosis and miosis only), and ipsilateral signs of cerebral or retinal ischemia. Those with dissections of the vertebral arteries may describe occipital and neck pain and posterior fossa symptoms, such as dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, and hemifield visual loss. Brain MRI may show a tapered arterial lumen or increased arterial diameter with an intramural hematoma. Noninvasive vessel imaging with MRA or CTA is typically sufficient. Comparative trials have not documented the superiority of anticoagulation in patients with dissections, and many are treated with aspirin.

Cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome is characterized by recurrent thunderclap headache (severe headache reach maximum intensity in 1 min) and multifocal constriction of intracranial vessels normalizing within 3 months of onset. Although subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is the most frequent cause of thunderclap headache, and some patients may experience an isolated sentinel leak before aneurysmal rupture, three episodes within 4 days would be highly unusual for SAH. Normal results of head CT scans and lumbar puncture (LP) effectively exclude SAH.

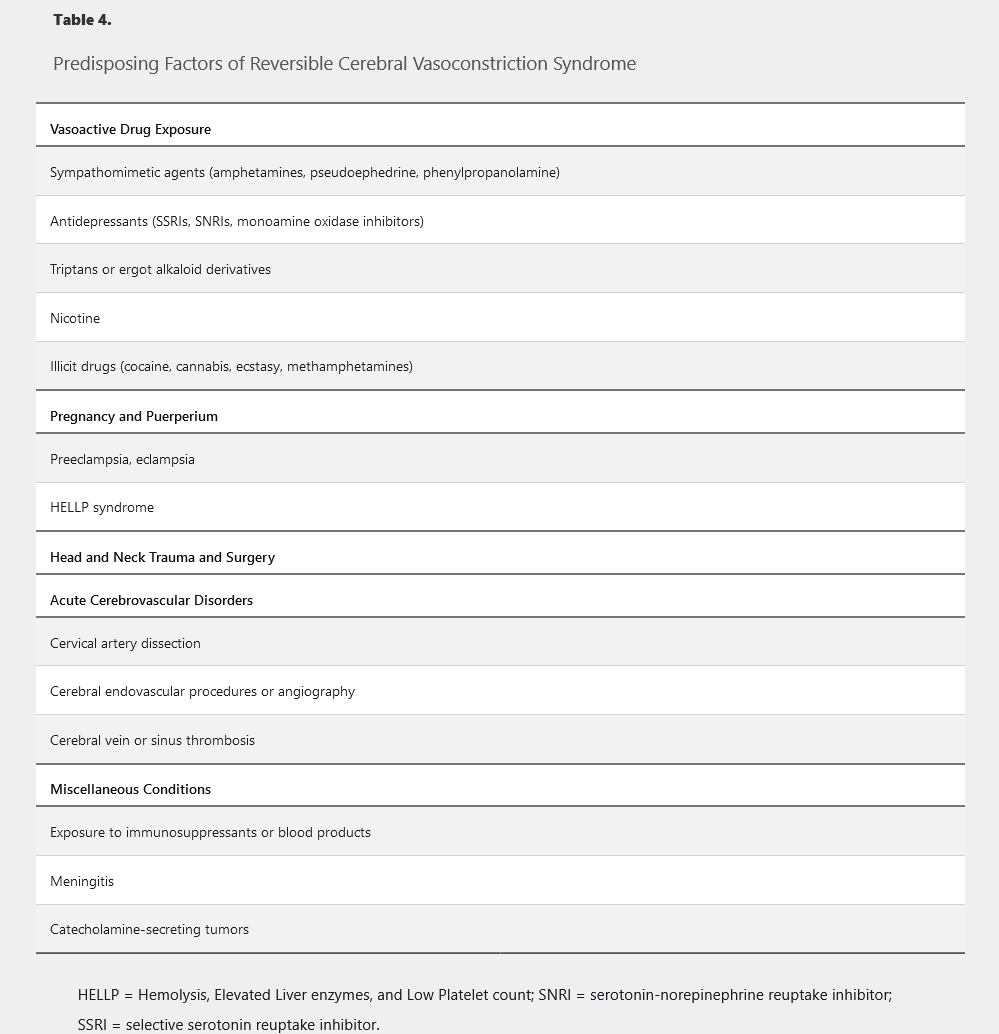

Predisposing factors are listed in Table 4. It is the second most frequent source of thunderclap headache. The headaches may be triggered by exertion, Valsalva maneuvers, emotion, or bathing. Focal deficits, encephalopathy, and seizures are seen in a minority of patients. Diagnostic evaluation should include noninvasive imaging of the brain and neck vessels with MRA or CTA and CSF analysis. Digital subtraction angiography has been associated with transient neurologic deficits and is typically avoided. Results of head CT and lumbar puncture are both typically normal. Brain MRI is more sensitive and may show areas of white matter edema primarily in the occipital and parietal lobes compatible with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Areas of ischemia or hemorrhage may be seen in the parenchyma, and a subdural or subarachnoid hemorrhage also may be found in some patients. Management begins with resolution of predisposing factors, avoidance of physical exertion, and management of blood pressure. Verapamil and nimodipine are the drugs of choice. Glucocorticoids may worsen the clinical course and should be avoided. Repeat MRA or CTA is necessary at 12 weeks to document resolution of vasospasm, at which time medication is tapered.

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Increased intracranial pressure in the absence of any vascular or space-occupying lesion is the hallmark of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) (also known as pseudotumor cerebri). Approximately 90% of affected persons are women of childbearing age with an elevated BMI. IIH is associated with the following conditions:

- Hypervitaminosis A

- Use of the tetracycline class of antibiotics

- Retinoic acid use

- Kidney failure

- Endocrine disorders (hypoparathyroidism, Addison disease)

- Use of estrogen and progesterone supplements and pregnancy

- Glucocorticoid use or withdrawal

Headaches, visual symptoms, and intracranial noises (pulsatile tinnitus) are the most common presenting symptoms of IIH. Head pain is nonspecific and may be similar to that of tension-type headache or migraine. Vision may be blurred, doubled, or periodically dim in brief episodes known as visual obscurations. Visual field testing is essential in the initial and follow-up evaluations of IIH. Although only 25% of patients may report visual symptoms, 90% have some abnormality on visual perimetry. Typical findings include blind spot enlargement and peripheral field reduction. Patients with atypical presentations (men older than 50 years, patients with normal BMIs) are less likely to report headaches and have a more benign visual prognosis.

Findings on neurologic examination include papilledema and, occasionally, ophthalmoplegia. Enhanced brain MRI with magnetic resonance venography may reveal widening of the optic nerve sheaths or flattening of the posterior optic globes but is otherwise unremarkable. An elevation in CSF opening pressure of greater than 250 mm H2O with normal CSF composition confirms the diagnosis.

Treatment of IIH is aimed primarily at preservation of vision. Patients with BMI elevation require introduction of a weight-loss program. Bariatric procedures have been shown to be helpful, when necessary. Acetazolamide is the drug of choice. Topiramate may be less effective but carries the potential added benefit of weight loss. Paresthesia, kidney stones, and taste perversion are possible adverse effects of both drugs. More immediate reduction in intracranial pressure may be accomplished through repeated lumbar punctures. Decompressive procedures, such as lumboperitoneal shunting or optic nerve fenestration, should be considered in patients with medically refractory IIH.

Key Points

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, which is suggested by the presence of headache, visual symptoms, and pulsatile tinnitus, occurs most commonly in women of child-bearing age who have an elevated BMI.

- Treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension is aimed primarily at preservation of vision; weight loss in patients who have an elevated BMI and acetazolamide are the treatments of choice.

Headaches from Intracranial Hypotension

Related Question

- Question 76

The most common source of intracranial hypotension is leakage of CSF after a lumbar puncture. The cardinal feature is a postural headache, typically worsening within 20 seconds of sitting or standing. Tinnitus, diplopia, neck pain, nausea, photophobia, and phonophobia are additional symptoms. Risk of developing symptoms may be reduced by using a small-caliber atraumatic needle but is unaffected by bed rest postprocedure. More than 50% of these headaches resolve spontaneously by day 4 postprocedure, and more than 75% by day 7. Persistent symptoms are treated with an autologous epidural blood patch (EBP), which causes resolution of symptoms in 80% to 90% of patients.

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension also classically presents with an orthostatic headache, but the interval between postural change and headache development is highly variable. When present for a period of weeks to months, the orthostatic component may fade completely. Associated symptoms are similar to those of post–dural-puncture headaches. Headache presentation may be thunderclap or subacute in nature. Diagnosis of intracranial hypotension can be confirmed by a CSF opening pressure of less than 60 mm H2O, but lumbar puncture may introduce another site of potential CSF leakage. Most clinicians rely on the contrast-enhanced brain-MRI finding of diffuse nonnodular pachymeningeal enhancement seen in nearly 80% of patients. Cerebellar tonsillar descent similar to that of a Chiari malformation, subdural fluid collections, decreased ventricular size, and engorgement of the pituitary gland are other common findings on MRI. Identification of the source of CSF leakage may be challenging. Most cases are empirically treated with lumbar EBP procedures. The success rate with “blind” patches is approximately 30%, and repeat procedures are commonly required. If two to three patches do not relieve the condition, attempts are made to further localize the site of CSF leakage using spinal CT myelography. Noncontrast spine MRI is a noninvasive alternative that also may show an extradural fluid collection at the site of the leak. Once identified, the site may be treated with targeted EBP or surgical repair. If no leak is identified, the studies can be repeated in 4 to 6 months.

Key Points

- The headache associated with intracranial hypotension caused by leakage of cerebrospinal fluid after a lumbar puncture is treated with an autologous epidural blood patch.

- The diagnosis of spontaneous intracranial hypotension is associated with the contrast-enhanced brain-MRI finding of diffuse nonnodular pachymeningeal enhancement in nearly 80% of patients.

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Related Question

- Question 87

Trigeminal neuralgia is the most common and most intense cranial neuralgia. Incidence increases with advanced age. Multiple sclerosis should be considered in those with onset before age 50 years. Pain is typically unilateral and localized to the maxillary and mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). The pains are brief, “shock-like,” or electric, lasting seconds to minutes. Paroxysms may be spontaneous or triggered by innocuous stimulation of the face. Refractory periods are common after a series of paroxysms. Ipsilateral autonomic features are rare. Neurologic examination is typically normal. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI detects nonvascular structural pathology (such as compressing and demyelinating causes) in 15% of patients. In the other 85%, brain MRA often identifies neurovascular contact between a loop of the superior cerebellar artery and the trigeminal nerve. Contact causing displacement or atrophy of the nerve has been associated with a greater likelihood of symptom development.

Management of trigeminal neuralgia begins with carbamazepine administration. Pain may resolve within a few days, although mild dizziness and drowsiness are common. Other adverse effects of the medication, including hyponatremia and agranulocytosis, are less common but necessitate intermittent monitoring. Alternative drugs are oxcarbazepine, baclofen, gabapentin, and lamotrigine. Approximately 30% of patients do not respond to trials of monotherapy or combined therapy. For those refractory to two-drug trials, surgical intervention should be considered. Nonsurgical options are effective in 50% of patients and include percutaneous radiofrequency coagulation, glycerol injection, or focused stereotactic (Gamma Knife) radiation. Posterior fossa microvascular decompression of the neurovascular contact zone is a more invasive and more effective option. It should be prioritized in those with low surgical risk.

Key Points

- Contrast-enhanced brain MRI detects nonvascular structural pathology in 15% of patients with trigeminal neuralgia, and brain magnetic resonance angiography often identifies neurovascular contact between a loop of the superior cerebellar artery and the trigeminal nerve in the other 85%.

- Initial management of trigeminal neuralgia is with carbamazepine; if medical therapy fails, focused stereotactic (Gamma Knife) radiation, glycerol injection, or posterior fossa microvascular decompression may be effective.

Medication-Induced Headache

Headache is a potential effect of medication exposure or withdrawal. Oral contraceptives, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, β-adrenergic agonists, and nitrates are among the most commonly implicated drugs; they may cause headache de novo or aggravate an existing primary headache disorder. Withdrawal from caffeine or antidepressants also frequently provokes headache. Medication overuse headache (MOH), previously called “rebound” headache, is a highly prevalent condition affecting 1% of adults. This clinical syndrome may result from overtreatment with acute medication in patients with underlying migraine or tension-type headache. Use of triptans, ergot alkaloids, opioids, or combination analgesics for 10 or more days per month or simple analgesics for 15 or more days per month constitutes medication overuse. Affected patients often report daily or near-daily headache that is refractory to numerous treatment options. MOH is more common in midlife, in women, and in those with high baseline headache frequency. In those with migraine, opioids are associated with a 44% increase and butalbital compounds with a 70% increase in the risk of headache progression. These medications should be avoided in patients with recurrent primary headache disorders. Management of MOH involves discontinuation of the overused medication and the introduction of appropriate preventive medication directed at the primary headache disorder.

Key Point

- Medication overuse headache can result from use of triptans, ergot alkaloids, opioids, or combination analgesic agents for 10 or more days per month or simple analgesic agents for 15 or more days per month; treatment includes discontinuation of the overused medication and use of appropriate preventive medication directed at the primary headache disorder.

Primary Headache

Migraine

Diagnosis

Related Question

- Question 71

The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD), third edition (beta version), recognizes several subtypes of migraine, including migraine without aura, migraine with aura, and chronic migraine. Each is characterized by episodes of disabling headache lasting hours to days. Accuracy of diagnosis and management is enhanced by the use of formal ICHD criteria, although the POUND mnemonic (Pulsatile quality of headache, One-day duration, Unilateral location, Nausea or vomiting, Disabling intensity) is a helpful means of recalling the symptoms typically associated with migraines. Because of the extensive phenotypic variation, nearly half of migraine presentations are misdiagnosed. Neck pain (75%) and “sinus” symptoms, such as tearing or nasal drainage (50%), are both more common than features felt to be characteristic of migraine, such as vomiting or aura. In the presence of a stable clinical pattern of migraine and a normal neurologic examination, brain imaging is not indicated.

Migraine without aura is the most prevalent migraine subtype (Table 5). Although clinicians often emphasize unilateral location or pulsatile characteristics, moderate to severe pain is the most sensitive feature, and worsening by routine physical activity is the most specific element among the pain criteria. Photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea are each reported by approximately 75% of patients with migraine without aura.

The diagnosis of migraine with aura is made after two discrete aura episodes have occurred (Table 6). Aura may occur in 20% to 30% of patients with migraine. It frequently precedes pain but may occur during or without head discomfort. Aura symptoms involve positive and negative neurologic phenomena developing gradually and evolving over a period of 5 to 60 minutes. Resolution is gradual and complete. ICHD criteria recognize a number of aura subtypes. Typical aura involves any combination of homonymous visual, hemisensory, or language symptoms. Brainstem aura is defined by the presence of two of the following brainstem symptoms: dysarthria, vertigo, tinnitus, hypacusis, diplopia, ataxia, or decreased level of consciousness. Hemiplegic aura comprises any aura involving motor weakness. Both hemiplegic and brainstem auras are listed as contraindications for triptan use. Retinal aura involves monocular visual compromise. These auras need to be distinguished from ocular pathologies, such as retinal ischemia or detachment. Given an associated increased risk of stroke, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives should be avoided in women with migraine aura of all subtypes.

Chronic migraine is defined as headache for 15 or more days per month (Table 7). Transformation from acute to chronic migraine occurs in the general population at an annual rate of 3%. Older age, female sex, head trauma, major life changes or stressors, obesity, chronic pain, mood and anxiety disorders, and inadequate acute migraine management are risk factors. Acute migraine medication or caffeine overuse and exposure to nicotine may also raise the risk of or exacerbate chronic migraine; some patients with chronic migraine may have a secondary diagnosis of MOH. Patients with chronic migraine are more disabled and more likely to report migraine-related comorbidities (mood or anxiety disorders, sleep dysfunction, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia) than are those with episodic migraine.

Acute Migraine Management

Related Question

- Question 31

The acute treatment of migraine aims to eliminate pain and restore function. Goals of care involve freedom from pain, nausea, and sensory sensitivities within 1 to 2 hours and maintenance of such control through at least 24 hours. Because attack characteristics show significant inter-individual and intra-individual variability, different treatment options and strategies are required (Table 8). Guidelines recommend tailoring the treatments to the severity and symptomatology of the attack. Migraines awakening a patient from sleep or those associated with nausea and vomiting may require medication offered in parenteral or nasal formulations. Because consistency of response to any treatment rarely approaches 100%, most patients benefit from availability of two or more acute migraine therapies. Administration of medication at the time of mild pain has been shown to improve therapeutic outcomes when compared to treating moderate to severe headache; therefore, treatment should be started as early as possible in the disease course. Treatment should be limited to 10 days per month to avoid MOH.

Evidence-based guidelines recommend several simple and combination analgesic agents as first-line therapies for acute migraine. Acetaminophen has established efficacy only in migraine of mild to moderate intensity; data suggest the response may be enhanced by coadministration with metoclopramide. Aspirin administered alone or in combination with acetaminophen and caffeine also has established efficacy in acute migraine. The effectiveness of the NSAIDs ibuprofen, naproxen sodium, and diclofenac potassium is supported by strong evidence. Special formulations of these products have been shown to be more rapidly absorbed and effective than their standard tablet counterparts. These formulations include effervescent aspirin, solubilized ibuprofen, and diclofenac powder for oral solution.

Triptans are selective agonists at 5-hydroxytryptamine 1B and 1D receptors. They are migraine-specific agents with direct impact on trigeminovascular activation associated with migraine attacks. Triptans reverse intracranial vasodilation (1B) and provide neuronal inhibition at peripheral and central trigeminal nerve circuitry (1D). Guidelines recommend the use of triptans in patients with moderate to severe migraine who have not responded to NSAID therapy over a series of at least three migraine attacks. Current evidence suggests that all oral triptans possess nearly similar clinical efficacy. Orally dissolvable tablets are intestinally absorbed; their only advantage is use without the need to drink liquids. Nasal spray options may have more rapid onset, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract. Outcomes are similar to those of oral agents, but unpleasant taste, nasal congestion, or burning may be limiting factors. Subcutaneous sumatriptan provides the most rapid onset and achieves the highest response rates among all triptan agents and formulations. Local site reactions and more prominent “triptan” sensations characteristic of the class (flushing, chest or throat tightness, paresthesia) may be noted. Because of vasoconstricting properties, triptans are contraindicated in the presence of coronary, cerebral, or peripheral vascular disease; uncontrolled hypertension; or migraine with brainstem or hemiplegic auras. Lasmiditan, a highly selective 5-HT1F receptor agonist, and ubrogepant, a calcitonin-gene related peptide antagonist, lack vasoconstrictor properties for migraine are now approved for migraine headaches. Different formulations of one triptan may be used safely within the same day, but using a different triptan or an ergot alkaloid should be delayed by 24 hours. Despite labeling precautions, the concurrent use of triptans and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants is safe in most cases.

Other agents also are effective in the management of acute migraine. Ergot alkaloids have been used for years but have been largely replaced by triptans, which have preferable safety and tolerability profiles; parenteral and nasal formulations of dihydroergotamine are the most available and effective options among the ergot alkaloids. Dopamine D2 receptor antagonists (metoclopramide, prochlorperazine) are often used as adjuncts to analgesics or triptans. In addition to antiemetic properties, these agents can reduce migraine pain when delivered parenterally. Guidelines recommend avoiding the use of opioids and butalbital-containing compounds for acute migraine. In addition to the potential for dependence or addiction, use of these agents has been linked to an increased risk of transformation from episodic to chronic migraine. They should be used sparingly and only when more appropriate acute therapies are contraindicated.

Migraine with a duration lasting longer than 72 hours is known as status migrainosus. Many patients with this condition can be treated with several days of glucocorticoids. Severe cases of acute migraine or status migrainosus may require emergency department or inpatient management. The cornerstone of care in these settings is intravenous delivery of a dopamine antagonist. These are typically combined with intravenous diphenhydramine (to limit dystonic reactions), intravenous ketorolac, and hydration. Opioids may be associated with prolonged length of hospital stay and should be avoided. A more extended course of treatment involving repetitive intravenous dihydroergotamine with antiemetics over 2 to 3 days is very effective in the management of refractory status migrainosus.

Migraine Prevention

The goals of migraine prevention are the reduction of migraine frequency, intensity, and duration. None of the medications used for migraine prevention were designed for this specific purpose. The best agents may reduce migraine frequency by half in approximately half of the patients treated. Nonpharmacologic preventive measures are not only optimal but required. Trigger identification and avoidance are often helpful. Stress management techniques, such as relaxation therapy or biofeedback, have established efficacy. Regulation of sleep patterns, intake of small frequent meals, adequate hydration, and daily aerobic exercise are all extremely helpful. Regular work and school schedules should be encouraged. Stimulants (such as caffeine and nicotine) must be eliminated or limited. Diet should be modified to avoid additives or preservatives, such as monosodium glutamate and artificial sweeteners. There is good evidence to support the use of certain supplements, such as petasites (butterbur), magnesium, riboflavin, and feverfew.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis should be considered when the headache frequency reaches 5 days per month and almost always is initiated when the frequency exceeds 10 days per month. Data suggest preventive medication can reduce attack frequency and intensity, patient disability, and medical cost. Several weeks or months are often required before maximum benefit is achieved. Once a response occurs, the medications should be continued for a period of 6 to 12 months, at which point dose reduction or drug elimination may be considered. Evidence-based guidelines for pharmacologic prevention of episodic migraine have established Level A evidence supporting the use of five medications: three β-adrenergic blockers (propranolol, timolol, metoprolol) and two antiepileptic drugs (divalproex sodium and topiramate). Level B evidence is available for atenolol, two antidepressants (amitriptyline and venlafaxine), and several NSAIDs. No evidence supports the use of calcium channel blockers or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants in migraine prevention. Studies involving patients with chronic migraine are more limited, but efficacy in prevention has been shown with topiramate and onabotulinum toxin A. Migraine-specific biologic therapies have been developed and shown to be effective in the prevention of both episodic and chronic migraine. The monoclonal antibodies erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab target calcitonin gene–related peptide or its receptor. Guidelines recommend integrating these agents into prevention of episodic or chronic migraine after two or three adequate but unsuccessful trials of oral preventive medication. Treatment selection is informed by previous therapeutic trials, the presence of coexisting medical conditions, and patient preference.

Tension-Type Headache

The most prevalent primary headache condition, tension-type headache is defined by clinical criteria as a headache disorder that, unlike migraine, is mild to moderate in intensity and is not associated with nausea, severe sensory sensitivities, or neurologic symptoms (Table 9). Imaging is not indicated. Subclassification is based on monthly headache frequency: infrequent episodic (<1 day), frequent episodic (1-14 days), and chronic (15 or more days). Acetaminophen, aspirin, NSAIDs, and caffeine-containing compounds are effective acute treatments for tension-type headache. Amitriptyline and stress management techniques have modest benefit in prevention of tension-type headache, and some data support the use of acupuncture. Muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, opioids, and onabotulinum toxin A have no role in the management of tension-type headache.

Key Points

- Imaging is not indicated for tension-type headache.

- Acetaminophen, aspirin, NSAIDs, and caffeine-containing compounds are effective acute treatments for tension-type headache, but muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, opioids, and onabotulinum toxin A have no role in the management of tension-type headache.

Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias

Related Question

- Question 51

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are the most severe and stereotypic primary headache disorders. Pain is severe, localized to the periorbital or temporal areas, and associated with pronounced ipsilateral cranial autonomic features, such as nasal congestion or rhinorrhea and ptosis or miosis. The TACs, which include cluster headache, chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH), and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT), are differentiated by episode duration, frequency, and periodicity.

Cluster headache may last 15 to 180 minutes and recur one to eight times daily over a span of weeks to months; the shorter duration distinguishes cluster headache from migraine (Table 10). This headache is characterized by a cyclical nature in which periods of recurrent headache activity are interrupted by months to years of headache remission. Many of the attacks are nocturnal, and some may be provoked by alcohol ingestion. Episodes of CPH last 2 to 30 minutes and recur up to 40 times per day, whereas those of SUNCT last 1 to 600 seconds and may recur more than 100 times daily. SUNCT may be confused with trigeminal neuralgia, which is more likely mandibular or maxillary and lacks autonomic features. Unlike cluster headache, both CPH and SUNCT typically continue without periods of remission. Brain MRI should be performed initially to exclude structural lesions mimicking TACs.

Cluster headache has several acute and preventive options. Oxygen inhalation and subcutaneous sumatriptan are both effective in the treatment of attacks. A 2-week course of glucocorticoids may help reduce attack frequency at the onset of the cycle. Verapamil is the drug of choice for longer-term prevention of cluster headache. CPH is uniquely and universally responsive to indomethacin. Reports have suggested a small benefit from lamotrigine, but SUNCT are largely refractory to medical management.

Key Points

- Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias are the most severe and stereotypic primary headache disorders and include cluster headaches, chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing.

- Cluster headache is treated with oxygen inhalation and subcutaneous sumatriptan.

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania is universally responsive to indomethacin; short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing are largely refractory to medical management.

Other Primary Headache Syndromes

Related Question

- Question 64

Primary stabbing headaches (“ice-pick headaches”) are episodes of stabbing head pain lasting seconds and occurring in isolation or in series. There are no associated autonomic features. The location of pain is fixed in one third of patients and extratrigeminal in most patients. Those with migraine may be more likely to describe these attacks. Indomethacin can be helpful during cycles of more frequent attacks.

Cough headache develops abruptly with cough or Valsalva maneuvers and typically lasts seconds to minutes. Mild headache may continue for 1 to 2 hours. The severity of pain correlates with cough frequency. Advancing age and male sex may be risk factors. Brain MRI is indicated because secondary pathologies, most commonly a Chiari malformation, may be found in half of those affected. Indomethacin may reduce headache frequency during cycles of increased activity.