Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- related: GI

- tags: #GI

Overview

In the United States, gastrointestinal bleeding is a common gastrointestinal cause of hospitalization. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is defined as bleeding from the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. The mortality rate for patients with UGIB varies from 2% to 10% but is usually due to other factors related to comorbid diseases. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) occurs from the colon or anorectum. It is less common, typically less severe, and has a lower mortality rate than UGIB. Small-bowel bleeding, formerly called obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, is bleeding that does not appear to originate from the upper or lower gastrointestinal tract; it is relatively uncommon.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

UGIB can present in various ways, including hematemesis, "coffee-ground" emesis, melena, or hematochezia. Hematemesis is vomiting of bright red blood or clots. Coffee-ground emesis is the vomiting of dark, digested blood. Melena is black, tarry stool with a distinctive odor. Hematochezia is the passage of fresh blood or clots from the rectum.

Causes

Common causes of UGIB include peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal varices, and Mallory-Weiss tear. Peptic ulcer disease is the most common cause (50%), with most gastroduodenal ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori or NSAID use. Erosive esophagitis is a common endoscopic finding but only rarely causes clinically important UGIB. Therefore, in a patient with UGIB and erosive esophagitis, alternative causes for the bleeding should be excluded.

Bleeding gastroesophageal varices typically occur in the distal esophagus or proximal stomach in individuals with advanced liver disease. Bleeding risk of varices is proportional to varix size.

A Mallory-Weiss tear consists of a mucosal disruption at the gastroesophageal junction and typically forms after repeated episodes of severe vomiting or retching.

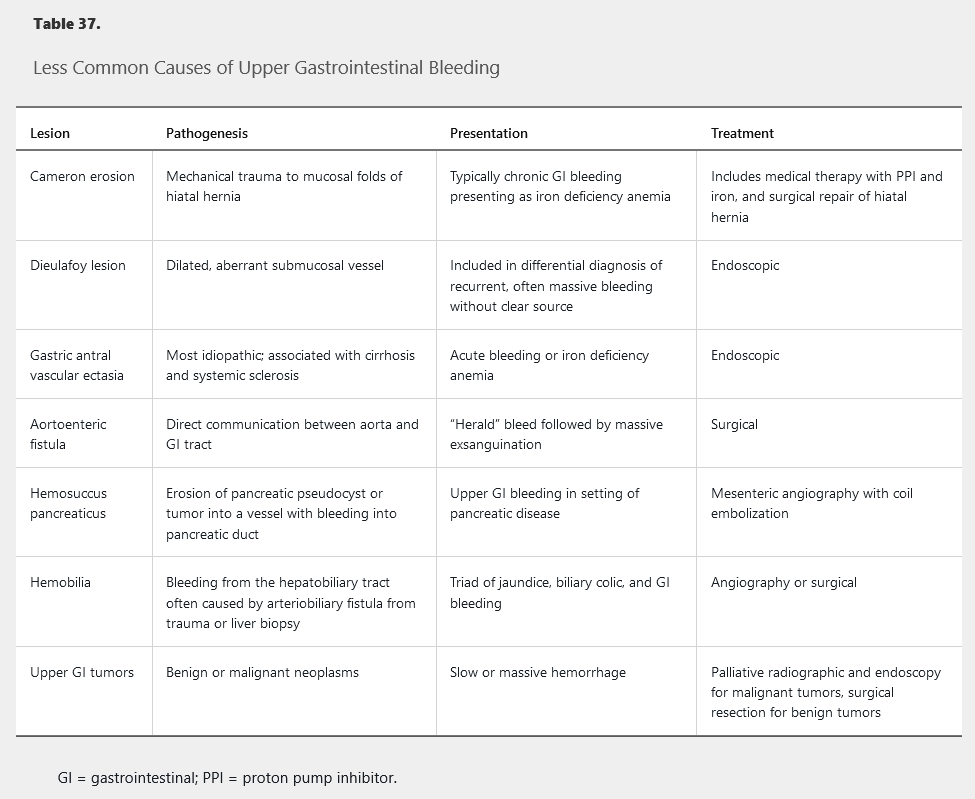

Less common causes of UGIB include Cameron erosions, Dieulafoy lesion, gastric antral vascular ectasia, aortoenteric fistula, hemosuccus pancreaticus, hemobilia, and upper gastrointestinal tumors (Table 37).

Evaluation

The initial step in the approach to UGIB is a risk assessment to determine the severity of UGIB. This risk assessment includes the measurement of vital signs and reviewing patient factors. Tachycardia (pulse rate >100/min), hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg), age older than 60 years, and major comorbid medical conditions are all associated with increased risk for rebleeding and death.

Findings of stigmata of chronic liver disease suggest a possible variceal source of bleeding.

Management

Patients with altered mental status, massive hematemesis, or an increased risk for aspiration should undergo endotracheal intubation. Hemoglobin levels should be measured. A restrictive transfusion strategy is recommended and initiated when the hemoglobin level is below 7 g/dL (70 g/L) in hemodynamically stable patients without preexisting cardiovascular disease. Patients with hypotension due to severe, ongoing UGIB and those with concomitant cardiovascular disease should be transfused before the hemoglobin level decreases below 7 g/dL (70 g/L) to prevent the decreases below 7 g/dL (70 g/L) that may occur with fluid resuscitation alone.

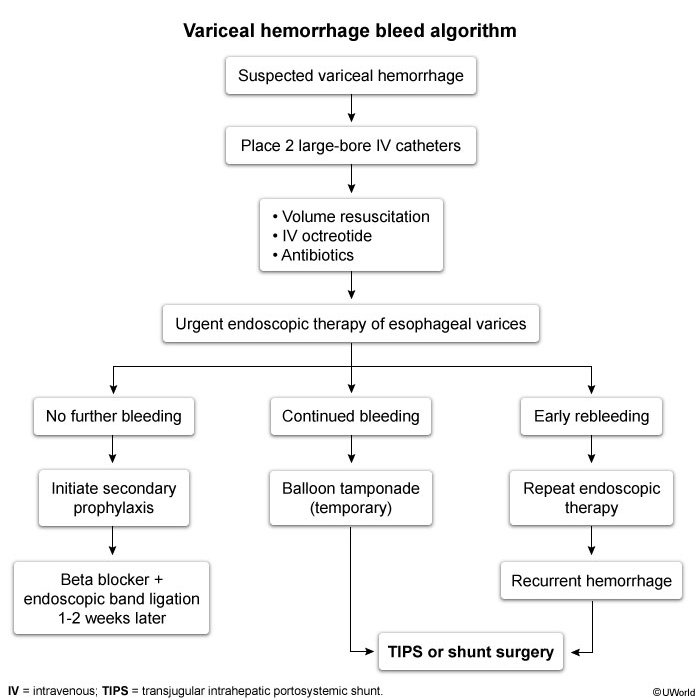

For variceal bleeding and other hemodynamically significant bleeding, resuscitative measures need to be initiated with the goal of hemodynamic stabilization. Two large-bore peripheral intravenous catheters (minimum 18 gauge) are required with initiation of crystalloid fluids, either normal saline or lactated Ringer solution, to maintain adequate blood pressure. See Disorders of the Liver for discussion of variceal bleeding, including prophylaxis.

Pre-Endoscopic Care

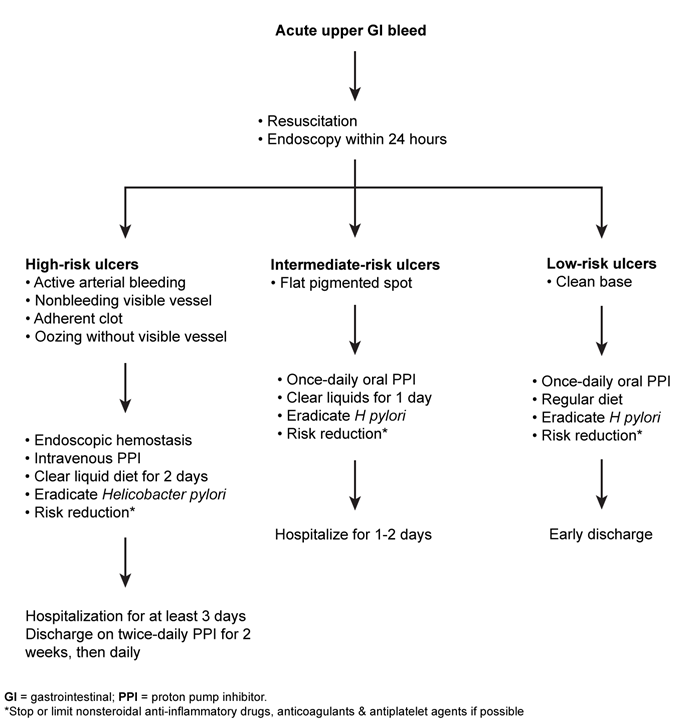

Intravenous proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy initiated before endoscopy decreases high-risk endoscopic stigmata seen (Figure 33 and Figure 34) but does not influence outcome. Octreotide and antibiotics (IV rocephin 1g q24 and then afterwards transition to cipro 500mg q12, 7 day course) should be initiated if variceal hemorrhage is suspected. Intravenous erythromycin given before endoscopy improves gastric visualization and decreases the need for repeat endoscopy, but it should be administered only when requested by the endoscopist, not routinely. Nasogastric tube lavage is not required, as it has shown no evidence of clinical benefit.

Patients with hemodynamic instability or active bleeding (hematemesis or recurrent large-volume hematochezia) should be admitted to an ICU for resuscitation. Other patients can be admitted to a regular hospital ward. Several decision rules and predictive models have been developed to identify patients who are at low risk for recurrent or life-threatening UGIB. The modified Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score is calculated using the blood urea nitrogen level, hemoglobin level, systolic blood pressure, and pulse rate. It predicts the need for clinical intervention, rebleeding, and mortality. Patients at low risk with a modified Glasgow-Blatchford score of 1 or less may be considered for early discharge or outpatient treatment.

Post-Endoscopic Care

Patients with low-risk stigmata (see Figure 35) can be fed within 24 hours of endoscopy, receive once-daily oral PPI therapy, and be discharged from the hospital. Patients with high-risk lesions and those with adherent clots requiring endoscopic treatment should receive intravenous PPI therapy for 72 hours to decrease risk for rebleeding and remain in the hospital for this interval. Twice-daily oral PPI therapy should continue for 2 weeks for high-risk lesions.

Ulcers with high-risk features for rebleeding (eg, active bleeding, adherent clot, visible vessel) typically require endoscopic treatment. Most rebleeding occurs in the first 72 hours, so patients should be monitored during this time while on high-dose intravenous PPI therapy. A clear liquid diet is advised as urgent interventions (eg, repeat endoscopy) may be needed if bleeding recurs. Stable patients may then be transitioned to a regular diet and oral PPI therapy and discharged. Routine "second-look" endoscopy has not been shown to be beneficial and is indicated only if there is rebleeding, poor visualization during the initial endoscopy (eg, due to blood/debris), or concern that initial endoscopic therapy was suboptimal.

When hemostasis is secure, antithrombotic agents can be restarted while continuing high-dose oral PPI therapy twice daily. Patients with idiopathic peptic ulcer disease, unrelated to NSAID use or Helicobacter pylori infection, should continue once-daily oral PPI therapy indefinitely because of the high risk for recurrent bleeding.

Endoscopic Evaluation and Treatment

Upper endoscopy is the primary diagnostic modality for evaluating UGIB. For patients hospitalized with UGIB, endoscopy should be performed within 24 hours of resuscitation; in those with rapid bleeding or suspected variceal hemorrhage, it should be done more emergently. The possibility of aortoenteric fistula should always be considered in patients who have had previous aortic graft surgery and who present with gastrointestinal bleeding because aortoenteric fistula is life-threatening, with a mortality rate of 50% even with surgical intervention. When there is a high degree of suspicion for an aortoenteric fistula, CT with intravenous contrast should be performed before endoscopy or other types of gastrointestinal evaluation.

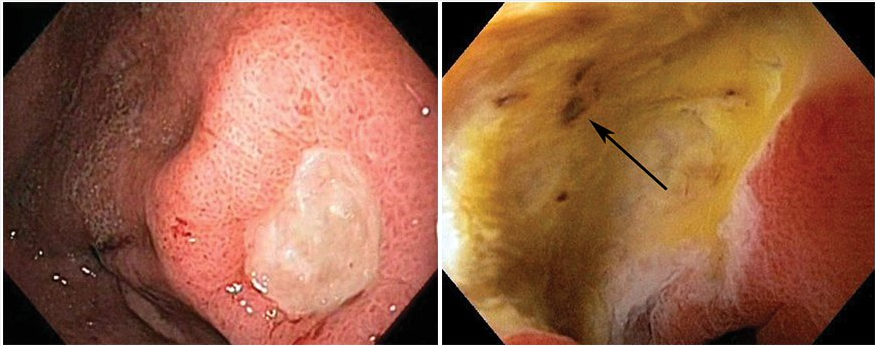

Endoscopy can determine the cause of bleeding and helps to risk-stratify the patient. Lesions at high risk for recurrent bleeding that require endoscopic treatment include: actively bleeding peptic ulcers, ulcers with nonbleeding visible vessels (see Figure 33), and ulcers with adherent clots (see Figure 34). An adherent clot should be irrigated with the intention of removing the clot; if clot removal is successful, treatment depends on the underlying lesion. Lesions at low risk for rebleeding (clean-based ulcers, ulcers with pigmented spots, and Mallory-Weiss tears) do not require endoscopic treatment (Figure 35). Endoscopic techniques include injection therapy, thermal devices, and endoclips. Most Mallory-Weiss tears (Figure 36) stop bleeding spontaneously. Endoscopic techniques such as injection therapy, thermal devices, and endoclips can be used for actively bleeding tears.

Ulcers at low risk for rebleeding, for which endoscopic therapy is not indicated. Left: Clean-based gastric ulcer with no blood vessels, pigmented spots/protuberances, or clots noted in the base. Right: Nonprotuberant pigmented spot (arrow) in a duodenal ulcer bed.

Ulcers at low risk for rebleeding, for which endoscopic therapy is not indicated. Left: Clean-based gastric ulcer with no blood vessels, pigmented spots/protuberances, or clots noted in the base. Right: Nonprotuberant pigmented spot (arrow) in a duodenal ulcer bed.

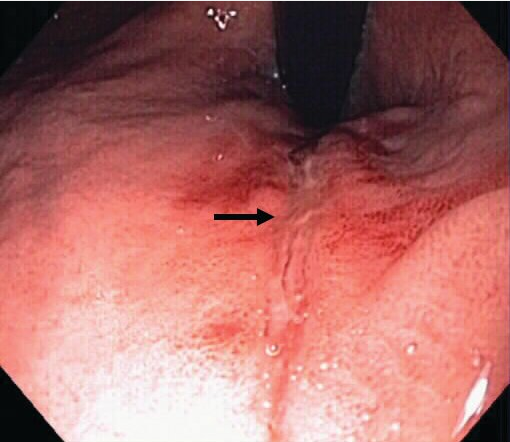

Mallory-Weiss tear. A superficial linear mucosal tear (arrow) seen on endoscopic retroflexion in the proximal stomach.

Mallory-Weiss tear. A superficial linear mucosal tear (arrow) seen on endoscopic retroflexion in the proximal stomach.

Aortoenteric Fistula

The patient presents with the classic “herald bleed” of aortoenteric fistula: a brisk bleed associated with hypotension that stops spontaneously and then is followed later by massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. An aortoenteric fistula is a communication between the aorta and the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly located in the distal duodenum, especially the third portion, because the duodenum is fixed and located just anterior to the aorta. The possibility of an aortoenteric fistula must be considered in a patient with previous aortic graft surgery who presents with gastrointestinal bleeding. It is a life-threatening condition, with a mortality rate of 50% even with surgical intervention. In this setting, the aortoenteric fistula is most commonly due to graft infection, and associated fever and leukocytosis occurs. When there is a high degree of suspicion for aortoenteric fistula, CT with intravenous contrast should be performed before other types of gastrointestinal evaluation because CT can be performed promptly and is noninvasive. CT can reveal evidence of graft infection, such as perigraft soft-tissue thickening or loss of tissue planes, and its reported sensitivity for aortoenteric fistula is 80% or greater.

Variceal Bleed

The initial therapy for acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage (Figure 37) is resuscitation in an ICU with the goal of maintaining hemodynamic stability and a hemoglobin of 7 g/dL (70 g/L). Overtransfusion can precipitate variceal rebleeding due to increased portal pressure.

The most effective approach for control of acute variceal hemorrhage is combined therapy with octreotide (somatostatin analog) and endoscopic therapy. Octreotide decreases splanchnic blood flow and lowers portal pressure; it should be initiated before endoscopic evaluation and continued for 3 to 5 days after variceal hemorrhage. Endoscopic variceal ligation within 12 hours of presentation is the endoscopic treatment of choice for hemostasis of active variceal hemorrhage, with a success rate of 90%. Subsequent endoscopy with further band ligation as needed to obliterate varices should be performed every 2 to 4 weeks.

Patients who develop variceal hemorrhage are at high risk for infection, such as pneumonia and urinary tract infection, and nearly 50% of patients with cirrhosis who are hospitalized with UGIB have a bacterial infection. Rates of rebleeding and death are reduced with prophylactic antibiotics (IV rocephin 1g q24 and then afterwards transition to cipro 500mg q12). Initiation of antibiotics at the time of hospitalization is recommended in all patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding, and antibiotic therapy should continue for 7 days after variceal hemorrhage, even in the absence of ascites.

Nonselective β-blocker therapy (propranolol, nadolol, or carvedilol) should be initiated in addition to endoscopic band ligation for secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage. The dosage of β-blockers should be increased as tolerated to obtain a resting pulse rate of 55 to 60/min.

For all causes of UGIB, endoscopic therapy should be repeated if bleeding recurs, but routine second-look endoscopy is not recommended. Interventional radiology or surgery is reserved for cases of rebleeding despite endoscopic treatment. For variceal bleeding, placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portocaval shunt is reserved for bleeding that is not controlled by drug and endoscopic therapy.

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Twenty percent of all cases of gastrointestinal bleeding originate in the colon or rectum. Most cases of LGIB stop spontaneously and have good outcomes; however, higher rates of morbidity and mortality are seen in older patients and in those with comorbid conditions. Patients with LGIB usually present with sudden onset of hematochezia (maroon or red blood per rectum). Occasionally, bleeding from the cecum or right colon may appear black and tarry, like melena. LGIB may present with additional symptoms of pain, diarrhea, or change in bowel movements.

Causes

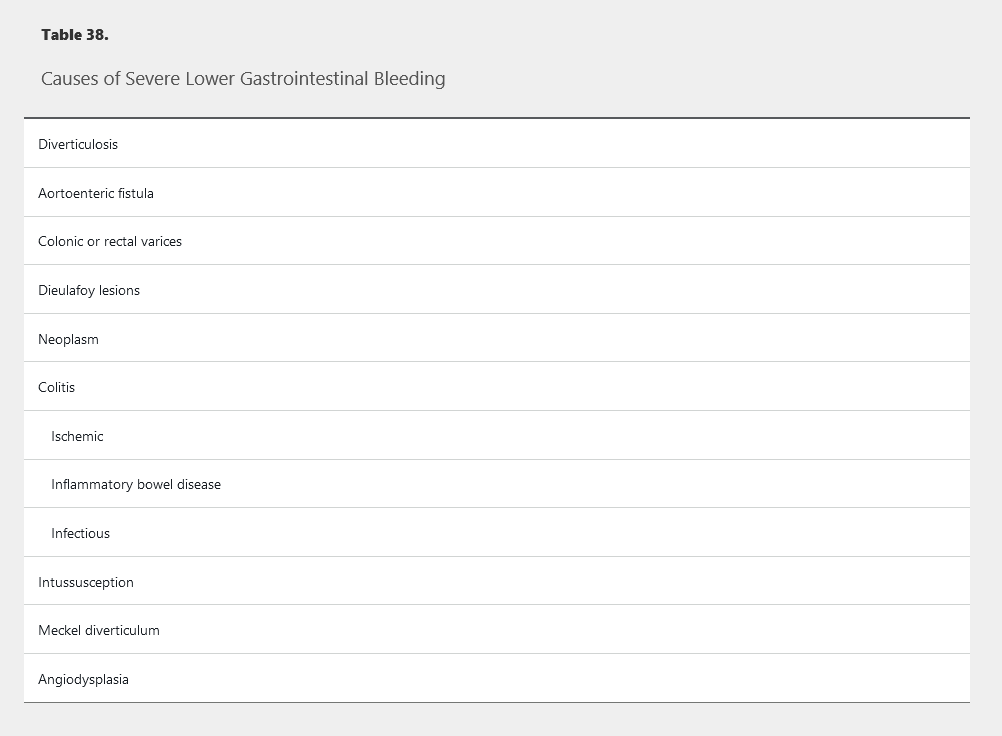

The most common cause of minor LGIB is hemorrhoidal bleeding. Hemorrhoidal bleeding is usually characterized by a small volume of bright red blood and does not cause hemodynamic instability or significant volume loss (see Disorders of the Small and Large Bowel for discussion of hemorrhoids). Causes of severe LGIB that may lead to clinical instability include diverticular bleeding, colonic angiodysplasia, postpolypectomy bleeding, Dieulafoy lesion, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, rectal varices, or malignancy (Table 38). Fifteen percent of patients with a presumed lower gastrointestinal source of bleeding are found to have an upper gastrointestinal source.

Diverticular bleeding is arterial, usually painless, occurs in the neck or dome of a diverticulum, and stops spontaneously in 75% of cases. In patients with diverticulosis, the risk for bleeding is estimated at 0.5 per 1000 person-years.

Angiodysplasia, also known as angiectasia or arteriovenous malformation, can occur throughout the colon but is most common in the right colon. Elderly patients and patients on anticoagulation therapy are at highest risk.

Postpolypectomy bleeding can occur immediately after polyp removal or days or weeks later. Risk is increased in patients with polyps larger than 2 cm in size, with polyps located in the right colon, and with resumption of antithrombotic therapy.

Patients with acute mesenteric ischemia usually present with severe abdominal pain, often out of proportion to physical findings. Diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hematochezia can occur with inflammatory bowel disease and infectious colitis. LGIB from a colon malignancy may be painless or associated with obstructive symptoms. Patients with cardiac disease, such as valve dysfunction or dilated cardiomyopathy, are at risk for acquired von Willebrand disease and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Evaluation

An initial patient assessment and hemodynamic resuscitation should be performed simultaneously. The timing and quality of any previous colonoscopy should be assessed, as should whether or not polypectomy or biopsies were performed. The patient's medication history, especially use and dosing of antithrombotic agents, should be assessed, as well as personal history, risk factors for liver disease, other comorbidities, and recent illness.

Management

Resuscitation goals for patients with LGIB should be normalization of blood pressure and heart rate, as well as the transfusion of packed red blood cells if needed to maintain the hemoglobin level above 7 g/dL (70 g/L), with a threshold of 9 g/dL (90 g/L) in patients with massive bleeding, or when treatment may be delayed. Platelet transfusion to maintain counts above 50,000 cells/µL (50 × 109/L) is recommended in patients with active bleeding. The decision to discontinue or reverse anticoagulant agents should balance the risk of ongoing bleeding with the risk of thromboembolic events and often requires a multidisciplinary approach.

CT angiography (CTA) is the initial diagnostic test in patients who are hemodynamically unstable or have rapid ongoing bleeding. Upper endoscopy may be a reasonable first choice in patients at risk for a rapidly bleeding upper gastrointestinal source as a cause of hematochezia. If CTA does not show a source of bleeding in the unstable or rapidly bleeding patient, upper endoscopy should be performed immediately.

Among hemodynamically stable patients without evidence of rapid bleeding, colonoscopy is the first test of choice in patients with LGIB. It should be performed within 24 hours of presentation after adequate colon preparation in patients with significant bleeding. Colonoscopy identifies a source of LGIB in two thirds of patients.

Radiographic studies should be considered in patients with ongoing bleeding who do not respond to resuscitation, patients who cannot tolerate colonoscopy or colon preparation, or patients in whom a source of bleeding is not identified endoscopically. Techniques include CT angiography, angiography, and, less frequently, tagged red blood cell scintigraphy.

Catheter-based angiography with embolization should be performed as soon as possible if CTA shows active bleeding. Angiographic embolization is also frequently used to stop persistent or recurrent diverticular bleeding because endoscopic approaches are limited due to the typical location of the vessel inside a thin-walled diverticulum. Surgical consultation is usually reserved for patients who do not respond to endoscopic or radiographic measures.

The risk for rebleeding is highest in patients with diverticular bleeding (9% to 47%) and angiodysplasia bleeding (37% to 64%). For prevention of recurrent LGIB, nonaspirin NSAIDs should be avoided, particularly after diverticular or angiodysplasia bleeding. Decisions on continued use of antiplatelet or anticoagulants and timing of resuming therapy must balance the likelihood of rebleeding and thrombotic risk. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease should be discontinued and not restarted. In patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease, aspirin for secondary prevention should be discontinued only if necessary and be restarted as soon as possible after hemostasis is achieved.

Small-Bowel Bleeding

The term small-bowel bleeding is preferred to obscure gastrointestinal bleeding because in many clinical situations the cause of the bleeding can now be identified. Patients with small-bowel bleeding often have normal results on upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. Small-bowel bleeding can be characterized as overt or occult. In patients with visible bleeding (either melena or hematochezia), it is overt. In patients who present with anemia but no gross signs of bleeding, the bleeding is considered occult. It is estimated that 5% to 10% of gastrointestinal bleeding occurs between the ligament of Treitz and the ileocecal valve; this is also known as midgastrointestinal bleeding.

Causes

The likely underlying cause of small-bowel bleeding varies with patient age (Table 39). Patients younger than age 40 years are likely to have bleeding due to inflammatory bowel disease, Dieulafoy lesions, neoplasia (leiomyoma, carcinoid, lymphoma, or adenocarcinoma), Meckel diverticulum, or a polyposis syndrome. Patients older than age 40 years are likely to have bleeding due to angiodysplasia, Dieulafoy lesion, neoplasia, or NSAID-related ulcers. Angiodysplasia (Figure 38) is the most common cause of small-bowel bleeding. It is found in 40% of cases and is often seen in elderly patients. Rare causes of bleeding include Henoch-Schönlein purpura, small-bowel varices or portal hypertensive enteropathy, amyloidosis, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, hematobilia, aortoenteric fistula, and hemosuccus entericus.

Evaluation

Related Question

- Question 90

A detailed medical history and physical examination are needed to narrow the differential diagnosis to a small-bowel source. Patients should be asked about NSAID use to evaluate for NSAID-induced small-bowel ulcers, aortic aneurysm repair (which raises concern for an aortoenteric fistula), necrotizing pancreatitis (which causes hemosuccus pancreaticus), or liver damage (such as trauma, tumor, or recent biopsy causing hemobilia). The presence of skin lesions may help determine an underlying diagnosis, including mucocutaneous telangiectasia (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome [Figure 39]) or dermatitis herpetiformis (celiac disease).

If the bleeding source is not identified, but clinical suspicion suggests that the cause of the bleeding is discoverable by a conventional endoscopic examination, a second-look endoscopy or colonoscopy should be done. The diagnostic yield is up to 25% with this approach.

Angiography

Conventional angiography is a diagnostic and therapeutic test. However, it is limited to detecting bleeding at rates greater than 0.5 mL/min. Clinical predictors of successful angiography include hemodynamic instability and the need for transfusion of more than 5 units of blood. Potential complications of angiography include acute kidney injury, systemic embolism, hematoma, and vascular dissection or aneurysm.

CT angiography uses multiple phases of contrast enhancement, including arterial enhancement. It can identify bleeding at rates as low as 0.3 mL/min, but its usefulness is limited because the patient must have active bleeding to identify the location.

Technetium-Labeled Nuclear Scan

Technetium 99m–labeled red blood cell or sulfur colloid nuclear scans are able to detect bleeding rates between 0.1 to 0.4 mL/min. Their accuracy in identifying a source of bleeding varies, ranging from 24% to 91%, and they do not provide for therapeutic intervention. A nuclear scan is often done before angiography to confirm the presence of active bleeding. Follow-up studies after a positive scan can include repeat endoscopy or angiography, both of which can offer more accurate localization and therapy.

Wireless Capsule Endoscopy

Capsule endoscopy employs a wireless capsule camera (Figure 40) that is swallowed by the patient to take images of the small bowel. The images are transmitted to a radiofrequency receiver worn by the patient. Capsule endoscopy is the preferred test for evaluating stable patients for causes of small-bowel bleeding after normal results on upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. Capsule endoscopy is able to visualize the entire small bowel in up to 90% of cases, with a diagnostic yield as high as 83%. Limitations of capsule endoscopy include the inability for therapeutic intervention and difficulty with localization of the lesion. The primary complication is possibility of capsule retention due to obstruction or strictures. The capsule can be retrieved by deep enteroscopy or surgery.

If there is continued concern for bleeding from the small bowel, specialized types of enteroscopy may be considered, including push, spiral, and balloon enteroscopy. These techniques allow visualization beyond the ligament of Treitz for diagnosis and the opportunity for therapeutic intervention. In general, the rates of complications are low, but complications can include perforation and in the case of balloon enteroscopy, ileus and pancreatitis.

Small-Bowel Imaging

Endoscopy has replaced imaging for the initial evaluation of suspected bleeding from the small bowel.

Barium-based examinations are no longer recommended for the evaluation of small-bowel bleeding because of low diagnostic yields. CT enterography is beneficial in diagnosing small-bowel masses and has shown a diagnostic yield of 40% for bleeding. Due to insufficient data, MR enterography is not recommended for the evaluation of small-bowel bleeding. However, it can be considered in patients younger than age 40 years, and it offers lower exposure to radiation than CT.

Intraoperative Endoscopy

Intraoperative endoscopy occurring during laparotomy is often a last resort because it is the most invasive modality available. The diagnostic yield for small-bowel bleeding has been reported in the range of 58% to 88%; however, its use should be reserved for patients in whom all other diagnostic modalities have failed.

Management

After achieving hemodynamic stabilization, therapy is guided by the underlying source of bleeding. Vascular lesions (angiodysplasia) should be treated with electrocautery, argon plasma coagulation, injection therapy, mechanical hemostasis (hemoclips or banding), or a combination of these techniques. Medical therapy for vascular lesions may require a somatostatin analog, such as octreotide. Hormonal therapy no longer has a role in the medical management of small-bowel bleeding.

Tumors or masses require surgical intervention, and if massive bleeding is present, embolization of the bleeding vessel may be needed with the assistance of interventional radiology.

Anemia should be treated with blood transfusion acutely if needed and iron supplementation. If a causative agent is identified, such as an NSAID, the agent should be stopped. Patients with angiodysplasia in the setting of aortic stenosis (known as Heyde syndrome) benefit from valve replacement surgery. While not FDA approved, thalidomide, which inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor, has shown some benefit in decreasing bleeding in patients with vascular malformations of the gut.

Anticoagulation

Vitamin K and 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate should be administered to patients on anticoagulation with a supratherapeutic INR. The risk for continued bleeding on anticoagulation therapy should be weighed against the risk associated with stopping therapy. Furthermore, endoscopy should not be delayed for anticoagulation reversal. For patients with an INR in or slightly above the therapeutic range (up to 2.7), normalization of the INR does not reduce rebleeding risk but delays endoscopy and decreases the sensitivity of endoscopy to identify important prognostic indicators related to risk for rebleeding.

In patients receiving warfarin who have hemodynamically significant hemorrhage, warfarin should be discontinued and reversed with prothrombin complex concentrate and vitamin K.

In patients receiving non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, the anticoagulant should be discontinued on presentation, and, if significant hemorrhage is present, reversal with the appropriate reversal agent (idarucizumab or andexanet) should be considered.

Decisions regarding discontinuing antiplatelet therapy are based on whether the therapy is for primary or secondary prophylaxis. If aspirin is being taken for primary prophylaxis, then it should be discontinued because the risk for recurrent bleeding outweighs the benefit. Aspirin for secondary prophylaxis can be discontinued for 3 days but needs to be promptly resumed when hemostasis is secure. Decisions regarding discontinuing clopidogrel and other antiplatelet agents should be made in conjunction with a cardiologist.

Decisions about discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 receptor antagonist and aspirin in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome or coronary stent placement should be made in conjunction with a cardiologist. In patients with significant hemorrhage in whom a P2Y12 receptor antagonist must be discontinued, aspirin should be continued and the P2Y12 receptor antagonist restarted within 5 days.

When hemostasis is secure, antithrombotic agents can be restarted while continuing high-dose oral PPI therapy twice daily. In general, once endoscopic hemostasis has been achieved, anticoagulation should be reinitiated, and in most cases, this can be done on the same day as the procedure. After temporary discontinuation of warfarin, antithrombotic therapy should be reinitiated within 7 days of initial drug discontinuation to avoid an increased risk for a thromboembolic event.

The timing of resuming therapy with non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants depends on the risk profile, but generally resumption should occur within 7 days.

Re-anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin should be considered within 48 hours in patients at high thrombotic risk (that is, those with a mechanical prosthetic heart valve in mitral position, atrial fibrillation with prosthetic heart valve or mitral stenosis, or recent venous thromboembolism).