Disorders of the Small and Large Bowel

- related: GI

- tags: #GI

Diarrhea

Classification

Diarrhea is a condition marked by passage of a greater number of less-formed stools than normal. The classification of diarrhea as acute or chronic is determined by duration of symptoms: acute diarrhea is defined by duration of less than 2 weeks, whereas chronic diarrhea is defined by duration of at least 4 weeks. Acute diarrhea is usually caused by infectious agents; chronic diarrhea is most commonly noninfectious.

Acute Diarrhea

Causes

Causes of acute diarrhea are primarily infectious, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites. These can be divided into noninvasive and invasive causes. Noninvasive causes lead to watery diarrhea; they include Clostridium difficile, viruses (such as norovirus and rotavirus), Escherichia coli, cholera, cryptosporidia, and Giardia lamblia. Invasive causes lead to dysentery or bloody diarrhea and include Campylobacter, hemorrhagic E. coli, Entamoeba histolytica, Shigella, and Salmonella. Persistent diarrhea (lasting between 14 and 30 days) is usually caused by a parasitic infection. For example, Giardia lamblia can begin as an acute infection but then become persistent or even chronic. See MKSAP 18 Infectious Disease for further discussion of infectious diarrhea.

Evaluation

Acute diarrhea may be accompanied by abdominal cramping, tenesmus, flatulence, fever, nausea, and vomiting. For all patients with acute diarrhea, evaluation of hydration status is important. Stool testing for infectious causes depends on many factors, including suspicion of disease outbreak, severity of symptoms, duration of symptoms (>7 days), and whether an individual is considered at increased risk for infectious diarrhea (such as a worker in day care, health care, or food preparation). For example, individuals with Giardia present with watery diarrhea that can be explosive and is associated with bloating due to malabsorption. A stool enzyme–linked immunosorbent assay is the best diagnostic test for Giardia infection.

Management

Fluid therapy is the mainstay of treatment for acute diarrhea. In patients with severe diarrhea or travelers with cholera-like diarrhea, balanced electrolyte rehydration solutions should be used. Confirmed infection with C. difficile should be treated with metronidazole, vancomycin, or other agents, depending on patient comorbidities and clinical severity (see MKSAP 18 Infectious Disease for discussion of C. difficile infection). Treatment of diarrhea in travelers includes bismuth and loperamide to relieve symptoms and consideration of empiric antibiotics if symptoms are moderate or severe.

Chronic Diarrhea

Causes

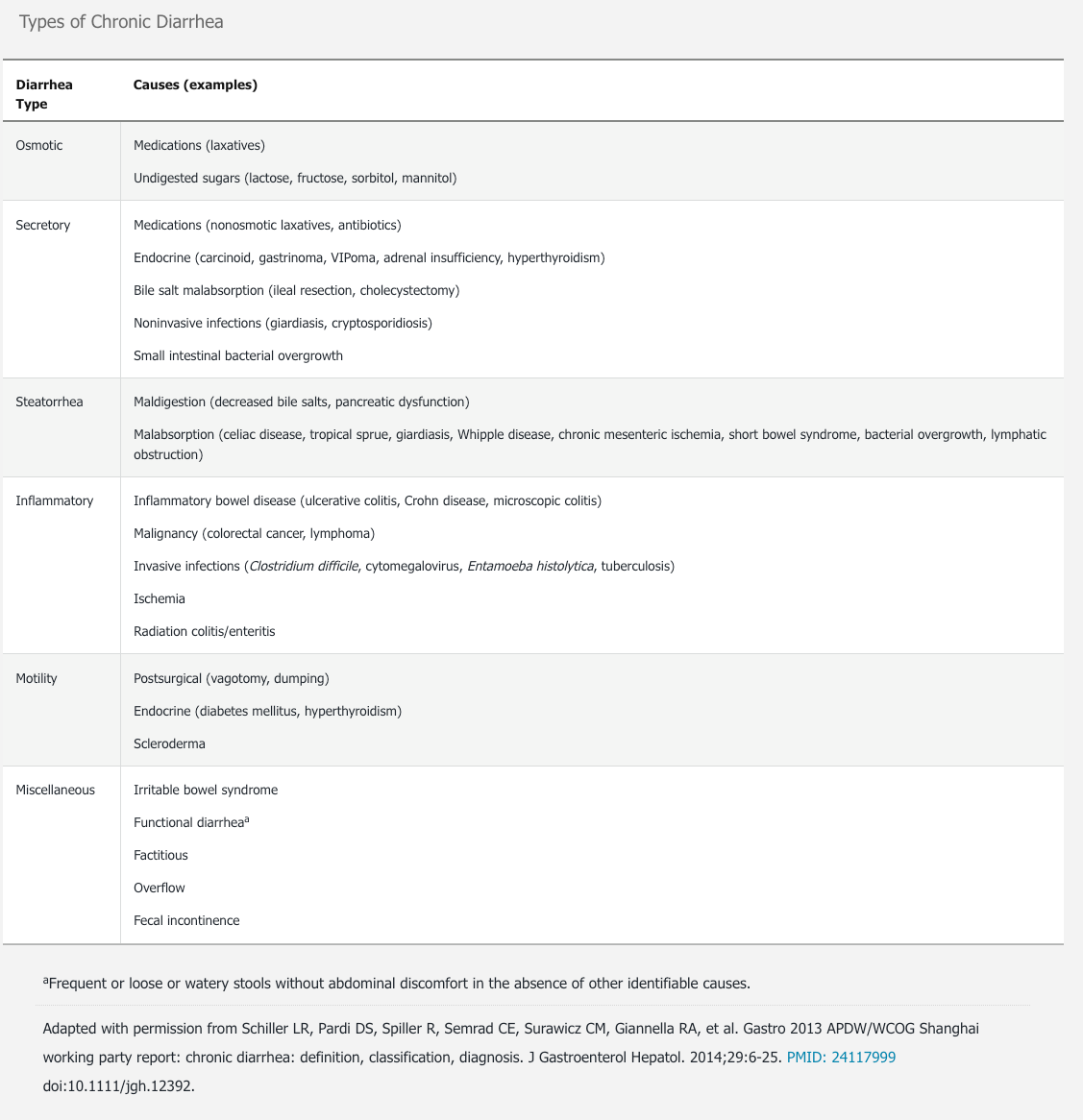

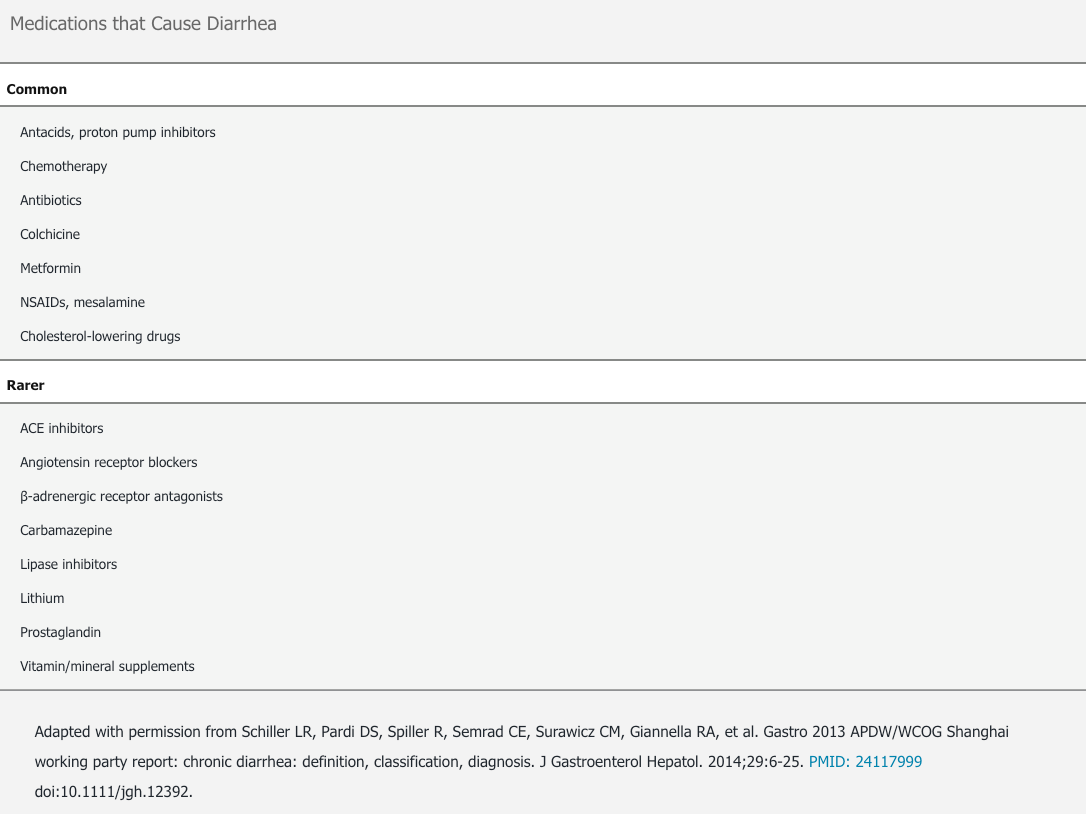

Chronic diarrhea can be grouped into six categories according to type of cause: (1) osmotic, (2) secretory, (3) steatorrhea, (4) inflammatory, (5) motility, and (6) miscellaneous (Table 17). These categories may overlap because some diseases have multiple mechanisms that cause diarrhea. The most common causes of chronic diarrhea are irritable bowel syndrome with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D) and functional causes. Medications are also an important cause of chronic diarrhea (Table 18).

Evaluation

The evaluation of chronic diarrhea includes a careful history and physical examination. Because IBS-D and functional causes are the most common causes, further diagnostic studies should be reserved for patients whose symptoms suggest another cause.

History and Physical Examination

The pattern of diarrhea can help determine the most likely diagnosis. Steatorrhea is often described as malodorous, greasy, or oily stools that float. The relation of symptoms to eating can also provide clues to the cause of diarrhea. Osmotic diarrhea occurs with eating and subsides with fasting, whereas secretory diarrhea does not subside with fasting. Information about specific dietary factors that commonly cause osmotic diarrhea, such as lactose, fructose, or artificial sweeteners (sorbitol) should be obtained. The patient should be asked about new medications (both prescription and nonprescription) and the timing of the initiation of medication in relation to the onset of diarrhea. Nocturnal symptoms are often related to inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Abdominal pain accompanying diarrhea suggests IBS-D, especially when a bowel movement relieves the pain. In evaluating chronic diarrhea, special attention should be given to features suggestive of malignancy, including rectal bleeding, weight loss, and age older than 50 years. Conditions such as IBS and microscopic colitis are more common in women than in men. IBS is most common in the third and fourth decades of life, whereas microscopic colitis is most common in the seventh and eighth decades.

Physical examination should assess for hydration and nutrition status, perineal disease suggestive of Crohn disease, and sphincter defects suggestive of fecal incontinence.

Additional Testing

The decision to do additional testing, including serologies, stool studies, imaging, and endoscopy, depends on the clinical scenario and likelihood of disease. Complete blood count, iron studies (including ferritin), thyroid-stimulating hormone level, fecal calprotectin, and testing for celiac disease and C. difficile infection may be considered.

Evaluation of the small intestine may include imaging with small-bowel radiography, CT enterography, or MR enterography to identify conditions that could lead to bacterial overgrowth, such as small intestinal diverticular disease, inflammation, or strictures. Upper endoscopy is indicated when small-bowel mucosal disease (such as celiac disease or chronic infection) is suspected. Capsule endoscopy can be used to visualize the small intestine but does not allow for sampling. Device-assisted enteroscopy (balloon or spiral overtubes) can be used in selected patients who require sampling of small-intestinal tissue based on abnormalities found on imaging or capsule endoscopy. The diagnostic yields for capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy are low in patients with chronic diarrhea and normal laboratory or imaging studies.

Colonoscopy is the primary diagnostic tool for evaluating causes of diarrhea related to the colon, such as IBD, microscopic colitis, chronic colonic infections, and malignancy. By definition, colon biopsies of the right and left colon are required to exclude microscopic colitis. Colonoscopy is especially important in patients with rectal bleeding and/or age older than 50 years.

In cases of chronic diarrhea without an underlying diagnosis, stool studies can help clarify the cause. Analysis of stool includes fecal weight, stool electrolytes, fecal pH, fat content, fecal calprotectin, and presence of blood and leukocytes. In watery stools, fecal electrolytes can be used to calculate the fecal osmotic gap:

290 – (2 × [stool sodium + stool potassium])

An osmotic gap of less than 50 mOsm/kg (50 mmol/kg) suggests secretory diarrhea, and a gap greater than 100 mOsm/kg (100 mmol/kg) suggests osmotic diarrhea.

The presence of blood or leukocytes in the stool suggests an inflammatory cause. A positive 72-hour stool collection for fecal fat confirms steatorrhea; a random fecal fat assessment may be helpful if a timed collection is not possible. A reduced fecal elastase level is useful in the evaluation of exocrine pancreatic function. When laxative abuse is suspected, a stool or urine laxative screen can aid in the diagnosis.

Additional testing may be warranted in immunocompromised patients (including HIV testing) and patients with secretory diarrhea. Patients found to have a small-bowel tumor in the setting of diarrhea should be considered for additional testing including radioimmunoassays for peptides and/or 24-hour urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid measurement for carcinoid tumors. Testing for carcinoid tumors should be limited to patients with chronic diarrhea and flushing.

Management

The management of chronic diarrhea is determined by its underlying cause. IBS-D and chronic diarrhea with a functional cause are treated with various medications aimed at slowing motility (loperamide), binding bile acids (cholestyramine), altering the gut microbiome (rifaximin), decreasing bowel contractions (eluxadoline), and modulating neurotransmitters (antidepressants).

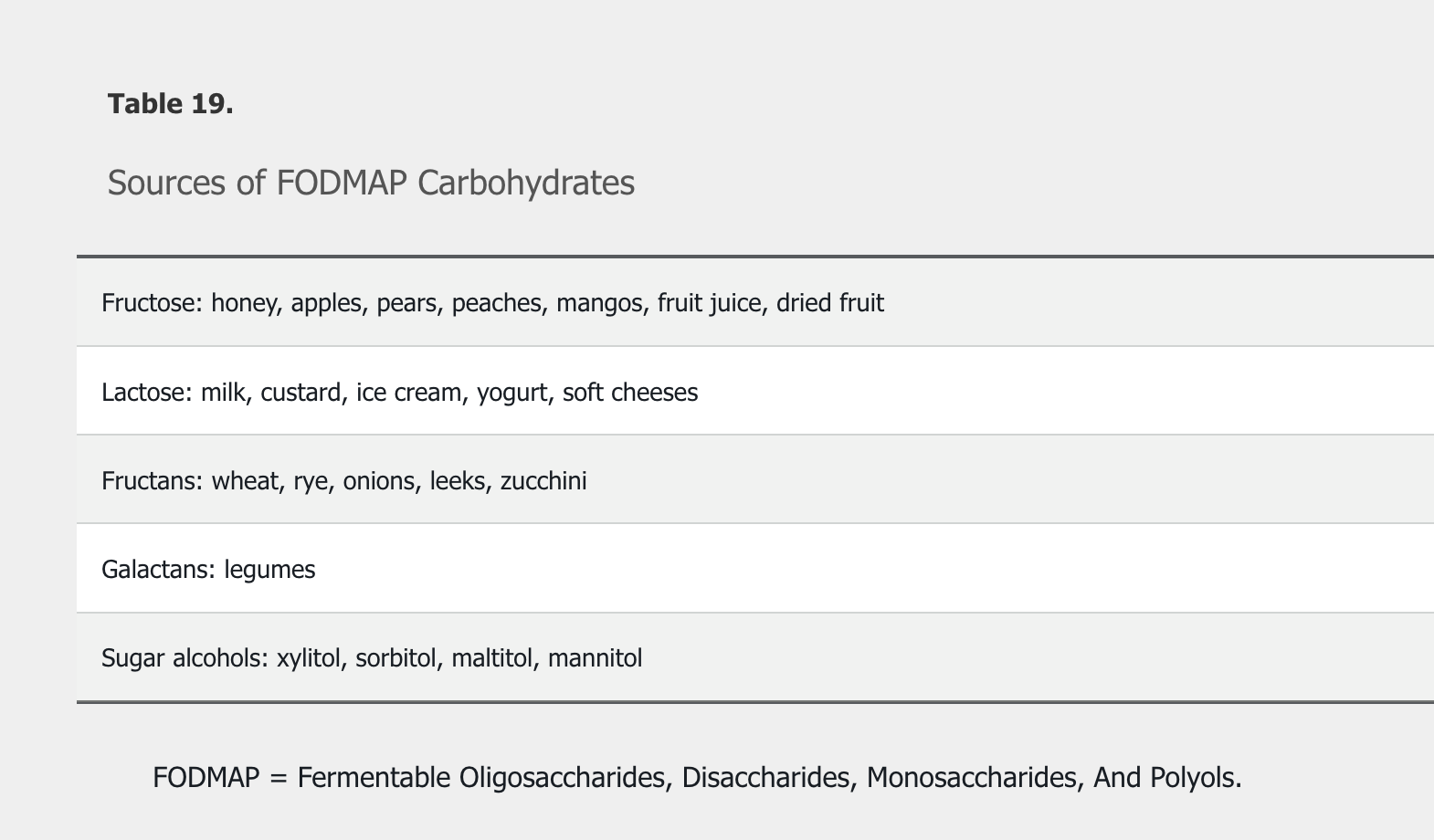

Treatment of osmotic diarrhea requires avoiding offending agents, such as following a low–Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, And Polyols (FODMAP) (Table 19) and lactose-free diet.

FODMAPs consist of short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed and rapidly fermented by gut bacteria, resulting in the production of gas and an increased osmotic fluid load within the gut lumen.

Treatment of secretory diarrhea is aimed at identification of the underlying cause as well as careful management of hydration. Repletion of fat-soluble vitamins is important in cases of fat malabsorption. Probiotics are not recommended for treatment of diarrhea.

Diarrhea induced by medications necessitates changing medications unless the benefits exceed the potential harms and the diarrhea is manageable from the standpoint of the patient.

Celiac Disease and Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity

Celiac disease is an immune-mediated disease that primarily affects the small intestine in response to dietary gluten. It is one of the most common causes of malabsorption, and only affects individuals who are genetically predisposed. The immune reaction leads to destruction of the small intestinal villi starting in the proximal duodenum. Although antibodies are produced as part of the immune reaction, they are not thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of celiac disease.

Testing

Testing should be pursued in patients with typical gastrointestinal symptoms or extraintestinal manifestations, and in those with increased risk (patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroid disease, or a first-degree family member with celiac disease). Gastrointestinal symptoms of celiac disease typically include chronic diarrhea, bloating, and weight loss, but may also include atypical symptoms, such as constipation and dyspepsia. Other manifestations include iron deficiency anemia, bone loss, abnormal liver aminotransferase levels, neurologic symptoms, and dermatitis herpetiformis (Figure 15). Patients may also be asymptomatic.

Dermatitis herpetiformis, a manifestation of celiac disease, is characterized by pruritic papules and transient, almost immediately excoriated blisters on the elbows, knees, and buttocks.

Dermatitis herpetiformis, a manifestation of celiac disease, is characterized by pruritic papules and transient, almost immediately excoriated blisters on the elbows, knees, and buttocks.

Ideally, testing for celiac disease should be done while the patient is on a gluten-containing diet. The best initial step is to test for IgA tissue transglutaminase antibodies. Because IgA deficiency is more common in patients with celiac disease, total IgA levels may also need to be measured. Testing for anti-deamidated gliadin peptide IgG antibodies and tissue transglutaminase IgG may also be used. Anti-endomysial antibodies are highly specific and can be helpful in making the diagnosis of celiac disease, but measurement with immunofluorescent microscopy is not reliable. The combination of tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies and anti-endomysial antibodies has a positive predictive value for celiac disease approaching 100%. Testing for anti-gliadin antibodies (IgA and IgG) should not be used because of low sensitivity and specificity. If clinical suspicion is high and initial testing is negative, additional testing should be pursued. Antibody testing is less reliable if the patient is on a gluten-free diet. In such patients, genetic testing for HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 should be considered; if those results are positive, a gluten challenge should be considered.

The vast majority of patients with celiac disease carry HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 genetic susceptibility; however, these genes can be found in up to 40% of the general population. Therefore, genetic testing can rule out disease but not confirm it. It may also be useful in patients in whom serologic testing was not completed at the time of diagnosis or when histologic changes are seen at biopsy but serologic test results are negative.

Diagnosis

A positive serologic test for celiac disease requires upper endoscopy with biopsies from the duodenum for confirmation of the disease. There are specific recommendations for the biopsy procedure to minimize false-negative results. Celiac disease is confirmed by the presence of increased intraepithelial lymphocytosis and villous blunting or atrophy of the duodenal villi. If biopsy results suggesting celiac disease are obtained before serologic testing, confirmatory serologic testing should be performed.

Management and Monitoring

Patients with a diagnosis of celiac disease should be educated about the gluten-free diet by a knowledgeable registered dietician. The treatment of celiac disease is lifelong avoidance of wheat, rye, and barley. Patients should be aware of gluten in medications and over-the-counter products. Dietary oats are generally safe in patients with celiac disease. Monitoring includes clinical assessment of symptoms and signs of celiac disease, assessment of dietary adherence, and confirmation of normalization of antibody levels. Antibody testing should be completed at 6 and 12 months after diagnosis and then annually to ensure response to therapy. Repeat upper endoscopy with biopsies should be considered for individuals with ongoing symptoms while adhering to a gluten-free diet, even if results of transglutaminase IgA testing are negative. Assessment of bone density and assessment for possible nutritional deficiencies (vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, folate) at the time of diagnosis should be considered to ensure adequate bone health.

Nonresponsive Celiac Disease

The most common cause of refractory celiac disease symptoms is gluten exposure. When a patient's symptoms do not resolve completely with adherence to a gluten-free diet, the accuracy of the original diagnosis of celiac disease should be reassessed. Other conditions that may account for ongoing symptoms include IBS, lactose or fructose intolerance, bacterial overgrowth, microscopic colitis, or IBD. Additional evaluation to exclude these as causes is critical before considering the patient to have refractory celiac disease.

A very small number of patients develop refractory celiac disease, in which small-intestinal inflammation persists despite adherence to a strict gluten-free diet. Individuals with refractory sprue are typically older than age 65 years and present with diarrhea, weight loss, dehydration, and nutritional deficiencies. In addition, some patients with refractory disease may have enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Possible medication-induced sprue, most commonly, olmesartan enteropathy, should be managed by discontinuing the offending medication. Patients with refractory celiac disease should be managed in a specialized celiac disease center.

In 2013, the FDA issued a warning that olmesartan medoxomil can cause intestinal symptoms known as sprue-like enteropathy and approved labeling changes to include this concern. The enteropathy may develop months to years after starting olmesartan. Drug-associated enteropathy can mimic refractory celiac disease with findings of villous atrophy and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes in the first part of the duodenum. The clinical presentation can include severe diarrhea, weight loss, and dehydration requiring hospitalization. Most of the reported cases of drug-associated enteropathy are caused by olmesartan, although other angiotensin-receptor blocking drugs have been implicated. In addition to adequate fluid resuscitation, the offending medication should be discontinued. In most cases of drug-associated enteropathy, symptoms and pathological changes resolve when the drug is stopped.

Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity

Nonceliac gluten sensitivity is defined by gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms that occur with gluten ingestion and subside with avoidance of gluten. By definition, celiac disease must be excluded. Because gluten-containing foods can also contain nonabsorbable carbohydrates, such as fructans, they can cause gastrointestinal symptoms due to osmotic mechanisms, as well as fermentation by colonic bacteria. Other than assessing symptom response after withdrawal of gluten, there is no diagnostic test for nonceliac gluten sensitivity.

Malabsorption

Short Bowel Syndrome

Short bowel syndrome is defined by a small-intestine length of less than 200 cm, with loss of absorptive area leading to maldigestion, malabsorption, and malnutrition. Surgery for strangulated bowel, Crohn disease, ischemia, trauma, and weight loss can all lead to short bowel syndrome.

Treatment depends on whether the patient has an intact ileocecal valve and colon or an ostomy. Patients with short bowel syndrome and an ostomy usually require parenteral nutrition and hydration. Those with extensive ileal resection should be tested and treated for vitamin B12 deficiency. Adjunctive therapies include antimotility and antisecretory drugs. Glucagon-like peptide 2 and its analog, teduglutide, are new pharmacologic agents for treatment of short bowel syndrome. Both have been evaluated in randomized trials and found to increase intestinal wet weight absorption and decrease parenteral fluid support in patients with short bowel syndrome.

Carbohydrate Malabsorption

Carbohydrates can be classified as monosaccharides (glucose, fructose), disaccharides (lactose, sucrose), oligosaccharides (maltodextrose), or polyols (sorbitol, mannitol). These short-chain carbohydrates are osmotically active and can lead to increased luminal water retention and gas production through colonic fermentation. These two actions can cause gastrointestinal symptoms, including gas, bloating, and diarrhea.

Lactose malabsorption is commonly due to loss of the brush border lactase enzyme in adulthood. Fructose malabsorption can also lead to gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating and diarrhea. Although both lactose and fructose breath tests are available, testing is often not required, as symptoms subside with exclusion of the sugar from the diet and recur with ingestion.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

IBD is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the gut that includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. In addition, microscopic colitis is considered a type of IBD with distinct clinical and pathologic features. The pathogenesis of IBD likely involves host genetic predisposition and abnormal immunologic responses to endogenous gut bacteria.

Risk Factors

The primary risk factor for development of IBD is family history, with a risk of approximately 10% for first-degree relatives of affected patients. Individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent have increased risk for IBD. Tobacco smoking increases the risk for Crohn disease and is protective for ulcerative colitis.

IBD has a bimodal age presentation, with an initial peak incidence in the second to fourth decades of life followed by a less prominent second peak in the seventh and eighth decades.

Clinical Manifestations

Ulcerative Colitis

The major symptoms of ulcerative colitis include diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, rectal bleeding, and tenesmus, with symptoms varying depending on the extent and severity of disease. Symptoms typically have a slow, insidious onset and often have been present for weeks or months by the time the patient seeks care, although ulcerative colitis may present acutely, mimicking infectious colitis.

Rectal inflammation (proctitis) causes frequent defecatory urges and passage of small liquid stools containing mucus and blood. Although bloody diarrhea is considered the hallmark presentation of ulcerative colitis, diarrhea is not always present. Patients with proctitis or proctosigmoiditis may have constipation. Abdominal pain is usually not a prominent symptom of ulcerative colitis; however, most patients with active disease experience vague lower-abdominal discomfort relieved with defecation. Physical examination in patients with mild or moderate ulcerative colitis is usually normal but may reveal mild lower-abdominal discomfort over the affected colonic segment. The presence of fever, nausea, vomiting, or severe abdominal pain indicates a severe attack or complication such as superimposed infection or toxic megacolon.

Crohn Disease

The clinical presentation of Crohn disease may be subtle and varies depending on the location and severity of inflammation along the gut axis as well as the presence of intestinal complications such as abscess, stricture, or fistula. Compared with ulcerative colitis, abdominal pain is a more common symptom of Crohn disease. The ileocecal area is the most common bowel segment affected by Crohn disease, and it often presents insidiously with mild diarrhea and abdominal cramping. Abdominal examination may reveal fullness or a tender mass in the right hypogastrium. Some patients present initially with a small-bowel obstruction caused by impaction of indigestible vegetables or fruit. Occasionally, the main presenting symptom is acute pain in the right lower quadrant, mimicking appendicitis. In patients with Crohn colitis, tenesmus is less common than in patients with ulcerative colitis because the rectum is often less inflamed than other colonic segments. Perianal disease is a common presentation of Crohn disease with anal fissures, ulcers, and stenosis.

Fistulae are a frequent manifestation of the transmural nature of Crohn disease and consist of abnormal connections between two epithelial surfaces (perianal, enteroenteric, enterocutaneous, rectovaginal, enterovesical). Drainage of fecal material from fistulae leads to symptoms such as passage of feces through the vagina (rectovaginal fistula). Intra-abdominal abscesses may form; the classic presentation is spiking fevers and focal abdominal tenderness, which may be masked by the use of glucocorticoids. Strictures represent long-standing inflammation and may occur in any segment of the gastrointestinal tract, although the terminal ileum is the most common site. Strictures may be secondary to fibrosis or severe inflammatory luminal narrowing. Patients with intestinal strictures often initially present with colicky postprandial abdominal pain and bloating that may progress to complete intestinal obstruction.

Table 20 summarizes the features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease.

Extraintestinal Manifestations

Inflammatory conditions involving extraintestinal structures, including the joints, eyes, liver, and skin, may occur in patients with IBD. These extraintestinal manifestations are categorized as either associated with active bowel disease or independent of bowel inflammation. Up to 30% of patients with IBD experience an extraintestinal manifestation at some time during the course of their disease; peripheral arthritis is the most common. See MKSAP 18 Rheumatology for discussion of IBD-related arthritis.

The two most common dermatologic extraintestinal manifestations are erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum. Erythema nodosum most commonly presents as single or multiple tender nodules on extensor surfaces of the lower extremities (Figure 16). Pyoderma gangrenosum typically presents as a papule that rapidly develops into an ulcer with undermined and violaceous borders (Figure 17). Both manifestations usually correspond to underlying IBD activity. See MKSAP 18 Dermatology for discussion of cutaneous manifestations of IBD.

Ocular extraintestinal manifestations of IBD include episcleritis and uveitis. Episcleritis is more common and consists of injection of the sclera and conjunctiva. It does not affect visual acuity and occurs in association with active bowel disease. Uveitis presents with headache, blurred vision, and photophobia. Uveitis is an ocular emergency requiring prompt referral to an ophthalmologist. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for discussion of episcleritis and uveitis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a major liver manifestation of IBD, occurring in 5% of patients. Patients most often present with isolated elevations in the serum alkaline phosphatase level. The liver disease is typically progressive and independent of the outcome of the IBD. See Disorders of the Liver for discussion of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of IBD relies on the integration of the clinical presentation, exclusion of infectious enteropathogens, endoscopic appearance, histologic assessment of mucosal biopsies, and radiologic features. IBD should be considered in any patient with chronic or bloody diarrhea. It is paramount to exclude infection, particularly with C. difficile and Shiga toxin–producing E. coli, by stool tests, especially in patients with acute onset of symptoms. Fecal calprotectin should be considered to help differentiate IBD from irritable bowel syndrome. Laboratory testing helps to assess disease activity. Common findings include anemia and hypoalbuminemia. Many patients develop iron deficiency anemia from chronic blood loss. Hematologic changes, such as thrombocytosis and leukocytosis, reflect active inflammatory disease. Persistently abnormal serum alkaline phosphatase levels should prompt further investigation for primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Endoscopy (either sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy) with biopsy is needed to help make the diagnosis of IBD. Colonoscopy is most commonly used to assess the extent and severity of disease. At presentation, 50% of patients with ulcerative colitis have disease limited to the rectum and sigmoid (proctosigmoiditis), 20% have left-sided disease (to the splenic flexure), and 30% present with pancolitis (to the cecum). Endoscopic findings range from decreased vascular pattern with erythema and edema in mild disease to large and deep ulcerations in severe disease. Histopathology characteristically shows features of chronic colitis with distorted and branching colonic crypts along with crypt abscesses.

Crohn disease has a different pattern of distribution from ulcerative colitis: 50% of patients have ileocolonic disease, 30% have isolated small bowel disease, and 20% have colonic disease. A minority of patients have isolated upper gastrointestinal tract or perianal disease in the absence of inflammation in the small bowel or colon. The earliest endoscopic findings of Crohn disease include aphthous ulcers, which can coalesce to form stellate ulcers, and a “cobblestone” mucosal appearance. A characteristic mucosal feature of Crohn disease is the so-called “skip lesion,” consisting of affected areas separated by normal mucosa. Granulomatous inflammation is characteristic of Crohn disease but uncommonly found on mucosal biopsies. Histopathology in small-intestinal Crohn disease will show chronic jejunitis or ileitis, and Crohn colitis will have histology similar to that in ulcerative colitis, with exception of granulomas.

Radiographic studies establish the location, extent, and severity of IBD. Patients with a severe attack of IBD require a plain abdominal radiograph to assess for a dilated colon (indicative of evolving toxic megacolon) or small-bowel obstruction (Figure 18). CT or MR enterography provides information about the location and severity of small bowel disease and the presence of complicating fistula, abscess, or stricture. Video capsule endoscopy is a highly sensitive modality for detection of small inflammatory lesions of the intestine, although it is not commonly required.

Treatment

The goals of therapy for IBD are to induce and maintain remission, and to prevent disease- and treatment-related complications. Four categories of drugs are used to treat IBD: 5-aminosalicylates, glucocorticoids, immunomodulators, and biologics. Stratification based on clinical severity is important in guiding IBD management. Currently, there are no validated or consensus definitions of mild, moderate, or severe IBD. For this synopsis, mild ulcerative colitis is defined as fewer than four to six bowels movements per day, mild to moderate rectal bleeding, absence of constitutional symptoms, and low overall inflammatory burden. Mild Crohn disease is characterized in patients who are ambulatory and are eating and drinking normally, with less than 10% weight loss and no disease-related complications, although patients may have diarrhea and abdominal pain. Patients with severe Crohn disease may be cachectic with significant weight loss and may have disease-related complications. These patients are often hospitalized. Patients with moderate disease fit in between the extremes.

Patients with IBD are at markedly increased risk for venous thromboembolism. The cause of thromboembolism is multifactorial and related to severity of disease, immobilization, and hospitalization. It is important that all hospitalized patients with IBD be given venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with subcutaneous heparin. Only in cases of massive gastrointestinal bleeding with severe anemia, tachycardia, and hypotension should nonpharmacologic prophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression of the lower extremities be used.

Pharmacotherapy

5-Aminosalicylates

5-Aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) are believed to have an anti-inflammatory mechanism of action. Unconjugated 5-ASA (mesalamine) is rapidly absorbed in the jejunum, allowing only 20% of the drug to reach the ileum and colon. Oral formulations of 5-ASA have been developed to reduce upper gastrointestinal absorption and enhance the delivery of the drug to the colon.

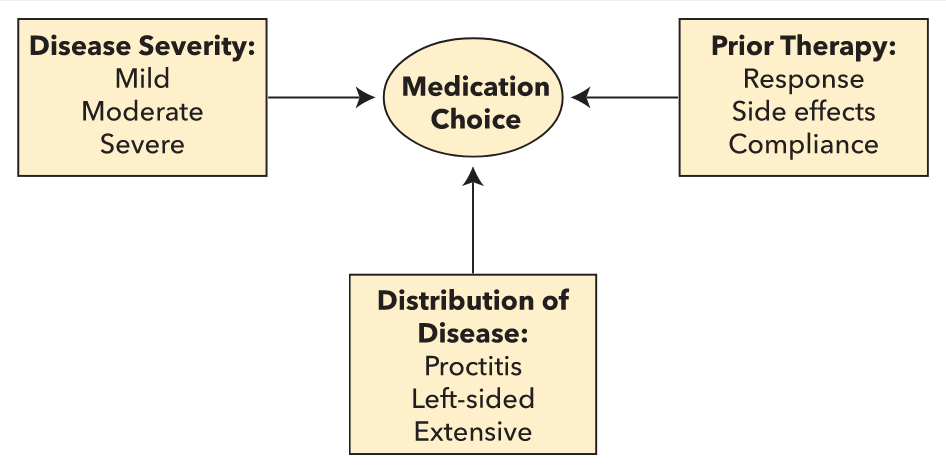

5-ASAs are the mainstay of treatment of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, with a dose-dependent response when used to induce disease remission. Three major factors need to be considered when choosing therapy for ulcerative colitis (Figure 19). Patients with proctitis or left-sided disease should receive topical therapy with 5-ASA suppositories or enemas. In mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, combined 5-ASA therapy (oral and topical) is superior for induction of remission compared with oral or topical therapies alone. Once remission is achieved, 5-ASAs are effective in maintaining it. 5-ASA compounds should not be used to maintain remission when biologic agents and/or immunomodulators were necessary to induce remission.

The main therapeutic 5-ASA agents are sulfasalazine, olsalazine, balsalazide, and delayed- and controlled-released mesalamine. Of the available agents, sulfasalazine has the most adverse effects, including fever, rash, nausea, vomiting, and headache, and is not considered first-line therapy. Sulfasalazine is a reasonable choice in patients already talking sulfasalazine in remission or in patients with prominent arthritic symptoms.

Despite the availability of several formulations designed to deliver the drug to the small bowel, 5-ASAs have not proved to be efficacious in small-bowel Crohn disease.

Glucocorticoids

Oral and intravenous glucocorticoids are commonly used to treat moderate to severe flares of IBD and are effective in inducing remission. However, glucocorticoids are not effective for maintenance therapy and have significant adverse effects. One formulation of oral budesonide is a controlled-release glucocorticoid with high first-pass metabolism in the liver and minimal systemic adverse effects. It is effective in inducing remission in mild to moderate ileocolonic Crohn disease. Another oral formulation is multimatrix (MMX) budesonide, designed to release the drug throughout the colon. It is effective in inducing remission in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis unresponsive to 5-ASAs and in moderate to severe disease.

Immunomodulators

Thiopurines (azathioprine and mercaptopurine, 6-MP) are immunomodulators used as glucocorticoid-sparing agents. They have a slow onset of action (2-3 months) and patients require a tapering glucocorticoid regimen to bridge the time interval until the thiopurines take effect. Thiopurines are no more effective than placebo in inducing short-term symptomatic remission but can be part of combination induction therapy with biologic agents. Thiopurine methyltransferase, a key enzyme involved in the metabolism of azathioprine and 6-MP, exhibits a population polymorphism that greatly increases the risk for bone marrow toxicity with use of these agents. Therefore, before initiation of thiopurine therapy, testing for the TPMT genotype or phenotype (enzyme activity) is recommended to help prevent toxicity by identifying individuals with low or absent TPMT enzyme activity. However, regardless of TPMT status, all patients require monitoring with complete blood counts and liver chemistry testing because 70% of patients who develop leukopenia while using these agents do not have TPMT mutations. Azathioprine and 6-MP are reported to cause the rare hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Azathioprine and 6-MP are effective in maintaining remission in patients with ulcerative colitis, should be considered in glucocorticoid-dependent patients, and can be combined with biologic agents. This includes patients who require two courses of glucocorticoids for induction of remission within 1 year, or patients who require intravenous glucocorticoids for acute disease flare.

Methotrexate is an immunomodulator that should be considered for use in alleviating signs and symptoms in patients with steroid-dependent Crohn disease and for maintaining remission. It is not effective in ulcerative colitis. Side effects of methotrexate include hepatotoxicity and interstitial pneumonitis, which can manifest with cough and dyspnea of insidious onset.

Biologic Agents

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. The anti-TNF agents infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab are used to treat moderate to severe Crohn disease resistant to glucocorticoids or immunomodulators. Infliximab is administered by intravenous infusion; adalimumab and certolizumab are given subcutaneously. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is more efficacious than monotherapy with either agent alone in achieving glucocorticoid-free remission and mucosal healing. There is increasing evidence for the use of biologic agents early in the course of disease. Before initiation of anti-TNF agents, patients should undergo testing for latent tuberculosis because of an increased risk for reactivation of tuberculosis during therapy. If latent tuberculosis is present, treatment with isoniazid should occur for at least 2 months before initiation of anti-TNF therapy. Patients should also be assessed for chronic hepatitis B viral infection before starting anti-TNF therapy and receive treatment if needed.

The anti-TNF agents infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab are used to induce and maintain remission in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, with infliximab being the preferred initial agent. Early use of biologics is appropriate after failure of 5-ASA treatment. Combination therapy with biologic therapy and immunomodulators (thiopurines or methotrexate) is more effective than monotherapy with either agent in achieving glucocorticoid-free remission and mucosal healing.

The anti-adhesion agents natalizumab and vedolizumab are effective in inducing and maintaining remission for moderate to severe Crohn disease. Vedolizumab is effective in inducing and maintaining remission in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, as well as in inducing remission when anti-TNF agents have failed. Natalizumab should be used for maintenance of natalizumab-induced remission of Crohn disease only if serum antibody to JC virus is negative because of risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a CNS demyelinating infection caused by reactivation of the JC virus. Testing for anti-JC virus antibody should be repeated every 6 months and treatment stopped if the result is positive. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks the biologic activity of interleukin-12 and -23 by inhibiting receptors for these cytokines on T-cells, is efficacious in severe Crohn disease, including when anti-TNF therapies prove ineffective.

Tofacitinib is a small-molecule agent that may be useful in ulcerative colitis when anti-TNF therapies are ineffective.

Medical Therapy for Fistulizing Disease

Fistulizing Crohn disease is difficult to manage and necessitates expert evaluation and coordination of care between internal medicine and surgery to provide the most appropriate therapy. As part of multimodality therapy, there is at least a moderate level of evidence that the antibiotics metronidazole and ciprofloxacin may be effective in simple perianal fistula. Infliximab is effective in perianal, enterocutaneous, and rectovaginal fistula, and tacrolimus in perianal and cutaneous fistula. The combination of infliximab and antibiotics is more effective than infliximab alone for perianal fistula.

Surgery

Indications for surgery in patients with Crohn disease include medically refractory fistula, fibrotic stricture with obstructive symptoms, symptoms refractory to medical therapy, and cancer. The guiding principle of surgery in Crohn disease is the preservation of bowel length and function, as the rate of disease recurrence after segmental resection is high. Patients with Crohn disease who undergo surgery require aggressive pharmacologic treatment with anti-TNF agents and/or immunomodulators to decrease the rate of postoperative recurrence of Crohn disease.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, total proctocolectomy with end-ileostomy or ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is performed for medically refractory disease, toxic megacolon, or carcinoma.

the diagnosis is toxic megacolon, a life-threatening condition that complicates approximately 5% of acute, severe cases of ulcerative colitis. Toxic megacolon is defined by the presence of toxicity (fever, tachycardia, hypotension, and leukocytosis) along with evidence of colonic dilation. Patients with this condition have an increased risk for complications such as colonic perforation. Intravenous fluid resuscitation, intravenous high-dose corticosteroids, and broad-spectrum antibiotics (for example, a third-generation cephalosporin with metronidazole) should be initiated in patients with toxic megacolon. Management requires close collaboration with a surgeon; therefore, emergent surgical consultation for consideration of subtotal colectomy is required because of the impending risk for perforation and peritonitis in patients with toxic megacolon. Some patients may respond to medical therapy with high-dose glucocorticoids (in addition to intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics), but there should be a low threshold for surgical intervention due to the potential harms associated with toxic megacolon.

Health Care Considerations

Patients with IBD are at increased risk for vaccine-preventable illnesses, and vaccines are underutilized in this patient population. Inactivated vaccines can be safely administered to all patients with IBD, regardless of immunosuppression. Patients with IBD should receive a seasonal influenza vaccine as well as the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Ideally, pneumococcal vaccination should occur before beginning immunosuppressive therapy. Live vaccines such as measles, mumps, rubella; varicella; and herpes zoster are contraindicated in immunosuppressed patients with IBD. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for discussion of vaccination strategies.

Women with IBD are at increased risk for developing cervical dysplasia; this risk is greater in women with Crohn disease than in those with ulcerative colitis, and is also greater in women using immunosuppressive therapy. Women with IBD should undergo Pap testing annually, and human papillomavirus vaccination is recommended.

All patients with IBD should be encouraged to stop smoking. Smoking increases Crohn disease activity and the risk for extraintestinal manifestations. Patients with IBD are at increased risk for metabolic bone disease due to use of glucocorticoids and diminished vitamin D and calcium absorption. Patients with Crohn disease are at greater risk than those with ulcerative colitis. Screening for osteoporosis should be considered in patients at increased risk. Avoidance of NSAIDs when possible and management of stress, depression, and anxiety are supported by low levels of evidence but are reasonable considering the associated low levels of harm.

Patients with IBD are at increased risk for developing cancers of the colorectum, cervix, and skin. Longstanding inflammation of the colorectum increases the risk for cancer. In patients with IBD (ulcerative colitis with disease proximal to the sigmoid colon and Crohn disease with more than one third of the colon involved), surveillance colonoscopy should begin 8 years after diagnosis and recur every 1 to 2 years thereafter. Primary sclerosing cholangitis increases the risk for colorectal cancer, and surveillance colonoscopy should begin at the time of diagnosis and recur yearly thereafter.

Patients with IBD are at increased risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers. Most of the risk has been associated with specific treatments; however, there is some evidence that IBD is associated with an increased risk for melanoma, independent of treatment. All patients with IBD should be advised to use sunscreen, wear protective clothing, avoid tanning beds, and have a yearly skin examination.

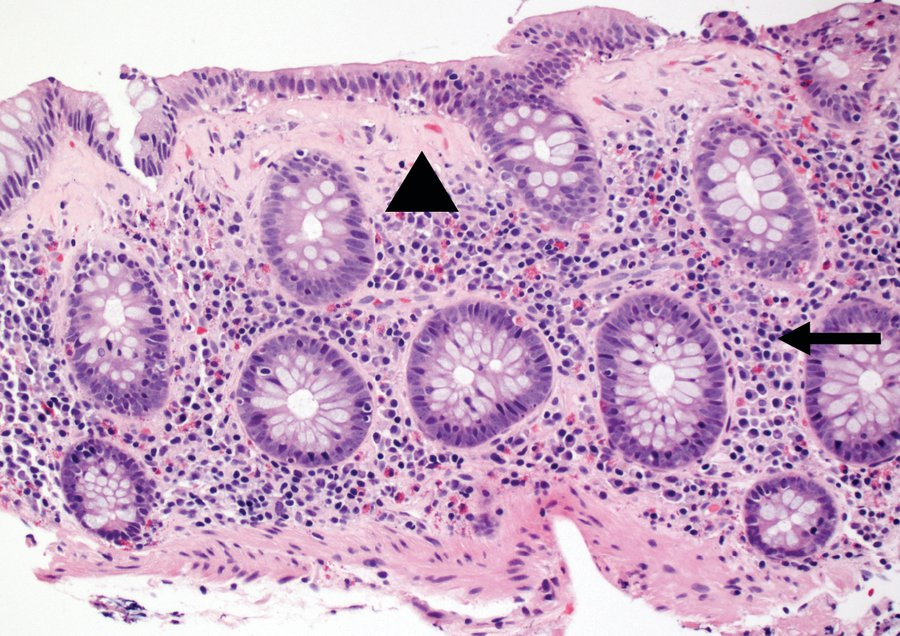

Microscopic Colitis

Microscopic colitis is a distinct type of IBD characterized by macroscopically normal mucosa with inflammatory changes seen only on histopathology of colon biopsies. It is subclassified into lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis (Figure 20) based on predominating histologic features. It predominantly affects middle-aged women and is associated with other autoimmune conditions, particularly celiac disease. It presents with abrupt or gradual onset of watery diarrhea that has a relapsing and remitting course over months to years, sometimes accompanied by mild weight loss. Diagnostic evaluation includes colonoscopy with random biopsies of the right and left colon.

Collagenous colitis: colon mucosal biopsy showing a pink, abnormal subepithelial collagen band (arrowhead) and lamina propria expanded by inflammatory cells (arrow).

Collagenous colitis: colon mucosal biopsy showing a pink, abnormal subepithelial collagen band (arrowhead) and lamina propria expanded by inflammatory cells (arrow).

Several classes of medications, including NSAIDs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and proton pump inhibitors have been associated with development of microscopic colitis. The first step in management is to discontinue any potentially causative medication. First-line treatments include supportive treatment with antidiarrheal agents such loperamide or bismuth subsalicylate. The next step is oral budesonide, which is efficacious but has a high rate of recurrent symptoms when discontinued. Unlike Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, there is no long-term increased risk for colorectal cancer in patients with microscopic colitis.

Constipation

Constipation is one of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms, affecting 20% of the general population. Constipation can present with symptoms including infrequent, difficult, or incomplete defecation. It can be acute or chronic, and either secondary or idiopathic in nature. Medications are the most common cause of secondary constipation; other causes include mechanical obstruction, systemic illnesses, altered physiologic states, and psychosocial conditions (Table 21).

Once secondary causes have been excluded, chronic constipation is considered to be functional (idiopathic). The definition of functional constipation has been refined by the fourth Rome working group for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Functional constipation is subtyped into categories of slow transit, normal transit, or dyssynergic defecation. Slow transit constipation is defined as the delayed passage of fecal contents through the colon based on objective transit testing (radiopaque marker study, scintigraphy, or the wireless motility capsule). Normal transit constipation is idiopathic constipation in which colonic transit times are adequate based on objective transit testing. Dyssynergic defecation (also termed pelvic floor dyssynergia, obstructed defecation, or outlet obstruction) refers to difficulty with or inability to expel stool as a result of some combination of abnormalities in contraction and/or relaxation of the muscles of the pelvic floor during defecation. In some cases, functional constipation can be the result of slow transit constipation and coexistent dyssynergic defecation.

Evaluation

A careful medical, surgical, and medication history identifies most causes of secondary constipation. The medication history should focus on the temporal relationship between medications and the development of constipation symptoms. The history should include an assessment for the presence of alarm features: hematochezia, acute constipation in elderly patients, unintentional weight loss, family history of colorectal cancer, unexplained anemia, and age older than 50 years with no previous colonoscopy. Anorectal examination, including a digital examination during Valsalva maneuver, is an important part of the physical examination because it may identify anatomic or functional causes of an evacuation disorder.

A flat plate radiograph of the abdomen is the most useful initial study because it can assess for the presence and distribution of excessive stool in the colon and/or rectum. Colonoscopy is used to assess blood in the stool, a sudden change in bowel habits, or unexplained anemia. It is also used for colon cancer screening in patients at average and increased risk due to family history of colorectal cancer. Additional imaging or laboratory studies should only be considered if clinically indicated. Physiologic testing, including colon transit testing, anorectal manometry, balloon expulsion testing, or defecography, is reserved for patients with constipation symptoms that do not respond to initial trials of laxative therapy.

Functional (idiopathic) constipation is diagnosed once secondary causes have been excluded.

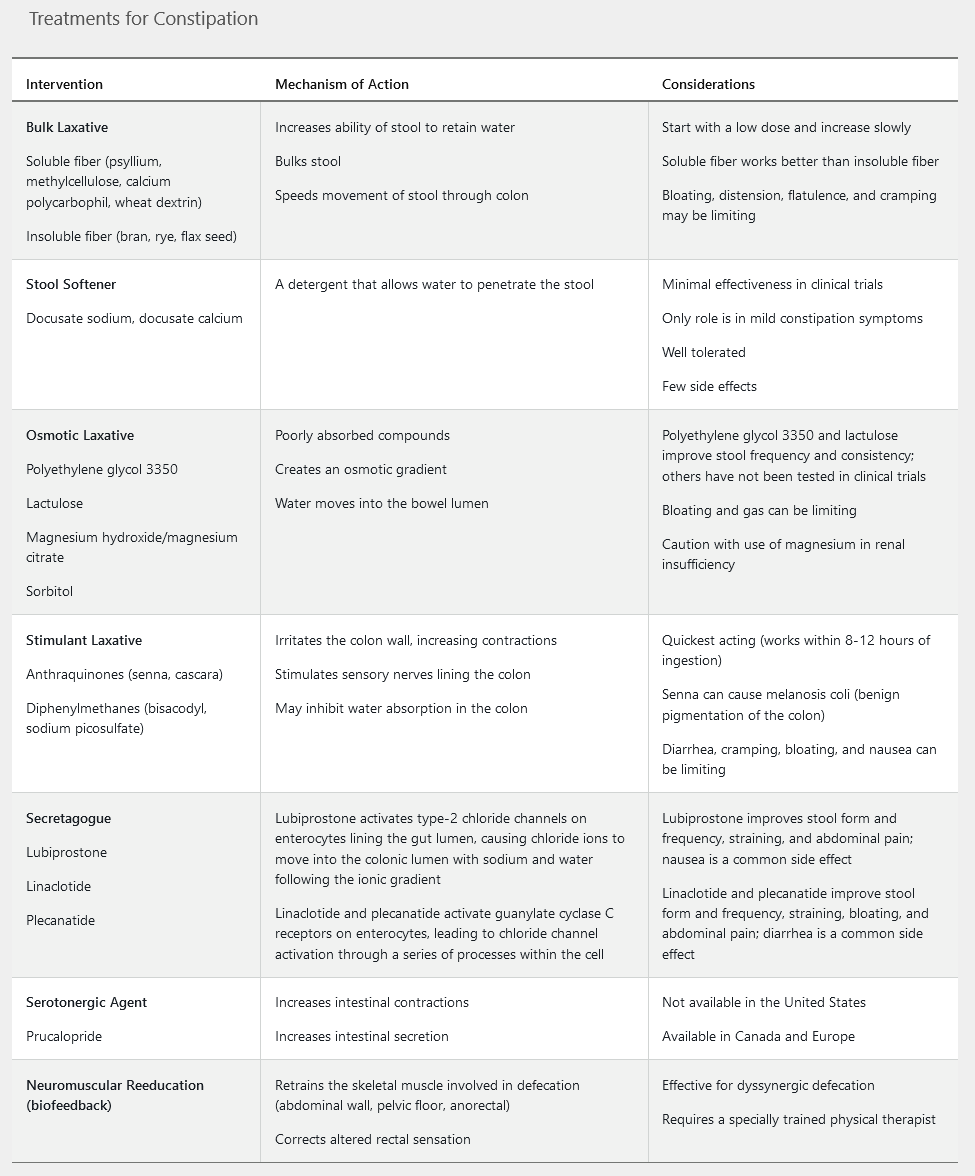

Management

Various treatment strategies may benefit patients with constipation when lifestyle and dietary interventions have been ineffective. Treatment options include bulking agents, stimulant laxatives, osmotic laxatives, stool softeners, secretagogues, and/or biofeedback (Table 22). The evidence for treatment efficacy is strongest for polyethylene glycol, lubiprostone, and linaclotide. Fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, magnesium, senna, docusate, and bisacodyl have the advantage of being available without a prescription. For refractory cases of constipation, combination therapy should include agents with different mechanisms of action, such as an osmotic plus a stimulant laxative.

Initial treatment of opioid-induced constipation should be the same as for other forms of constipation. For laxative-refractory opioid-induced constipation, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute recommends two peripherally acting µ-opioid receptor antagonists, oral naldemedine or subcutaneous methylnaltrexone, and naloxegol, a pegylated form of naloxone. The AGA Institute concluded evidence was insufficient to recommend either lubiprostone or prucalopride.

Linaclotide is a peripherally acting guanylate cyclase-C receptor agonist that is FDA approved for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation in adults. Linaclotide increases intracellular and extracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate, which results in chloride and bicarbonate secretion into intestinal lumen, increasing intestinal fluid content and accelerated transit time. Its superiority to placebo in the treatment of constipation was demonstrated in two 12-week, high-quality randomized controlled trials. Diarrhea occurred in 16% of patients receiving linaclotide (compared to 4.7% in those receiving placebo) in the 12-week clinical trials. The potential for diarrhea can be minimized by taking linaclotide on an empty stomach, ideally 30 minutes before the first meal of the day. Plecanatide is the second guanylate cyclase-C receptor agonist to receive FDA approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. Diarrhea was also the most commonly reported side effect of plecanatide therapy in the 12-week clinical trials (5% versus 1% in the placebo group). Lubiprostone, a chloride channel agonist, is a third agent with FDA approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. The most common side effects reported in clinical trials were nausea, reported by 29% of patients taking lubiprostone, and diarrhea, reported by 12%. The efficacy and safety of linaclotide, plecanatide, and lubiprostone have not been established in patients aged younger than 18 years nor in pregnant patients. Because of cost effectiveness, over-the-counter laxatives, such as fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, and bisacodyl, should be pursued first in patients with constipation, but they were ineffective in this patient.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

IBS represents a heterogeneous group of functional bowel disorders defined by the presence of abdominal pain in association with defecation and/or a change in bowel habits. Abdominal pain may worsen or subside with defecation. The altered bowel habits may include constipation, diarrhea, or a mix of both types. Other commonly reported symptoms include abdominal bloating and abdominal distention. The exact cause of IBS remains unknown, and there are no all-encompassing pathophysiologic mechanisms to explain the symptoms. IBS is more common in women and adults younger than age 50 years, and is frequently seen in association with psychosocial disturbance. There are no specific anatomic or physiologic abnormalities, nor are there any reliable biomarkers to define IBS. The diagnosis of IBS requires symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain at least 1 day a week for a period of 3 months, along with at least two of the following three additional criteria: pain related to defecation, change in stool frequency, or change in stool consistency. IBS can then be further subtyped into IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C), IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with mixed bowel habits, or IBS unclassified.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of IBS is no longer one of exclusion; instead, the diagnosis can reliably be made by clinical criteria in the absence of alarm features. Therefore, evaluation for IBS relies on a comprehensive history and physical examination. Fecal calprotectin testing to assess for inflammatory bowel disease and testing for giardiasis and celiac disease should also be considered in patients with chronic diarrhea.

Management

Management of IBS includes lifestyle and dietary modifications, and reassurance that the disease is benign. The focus is control of symptoms. There is limited evidence to suggest that exercise, stress management, and correction of impaired sleep can alleviate the symptoms of IBS.

The most common dietary intervention is an increase in fiber, either through diet or use of fiber supplements. Water-soluble fiber supplements such as psyllium are more effective than insoluble dietary fiber such as bran. Dietary restrictions can include avoidance of trigger foods, gluten (in the absence of celiac disease), dairy products, and FODMAPs (see Table 19). Randomized trials have shown that a low-FODMAP diet alleviates symptoms in patients with IBS. When these initial measures fail to relieve symptoms, medications, typically directed at the primary symptoms of IBS such constipation, diarrhea, or abdominal pain, are employed. The evidence supporting the use of the various agents is variable, with few rigorous studies showing long-term effectiveness.

Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Predominant Constipation

Several peripherally acting medications have demonstrated efficacy and safety in the treatment of IBS-C (see Table 22). The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has given a strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence for the use of linaclotide, followed by a conditional recommendation for the use of lubiprostone based on moderate-quality evidence and a conditional recommendation for the use of polyethylene glycol based on low-quality evidence in the treatment of IBS-C. Probiotics have uncertain benefit and should be used in the context of a clinical trial.

Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Predominant Diarrhea

Prescription medications with FDA approval for the treatment of IBS–D include rifaximin, eluxadoline, and alosetron. A 14-day course of rifaximin has shown superiority to placebo in relieving the global symptoms, bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stools associated with IBS-D for up to 10 weeks after treatment. A retreatment study of patients with recurring IBS-D symptoms after an initial course of rifaximin showed that a second 14-day treatment of rifaximin was superior to placebo in relieving abdominal pain and improving stool frequency for 4 weeks after treatment.

Eluxadoline (combination of a µ-opioid receptor agonist and a δ-opioid receptor antagonist) was superior to placebo in the treatment of men and women with IBS-D for up to 26 weeks based on a composite response of decreased abdominal pain and improved stool consistency in two randomized trials. Use of eluxadoline is contraindicated in patients without a gallbladder and in those with known or suspected biliary obstruction, Sphincter of Oddi disease or dysfunction, ingestion of three or more alcoholic beverages a day, history of pancreatitis or structural disease of the pancreas, severe hepatic impairment, or history of severe constipation.

Alosetron (a selective 5-HT3 antagonist) has alleviated abdominal pain and the global symptoms of women with IBS-D in pooled data from several randomized trials. The AGA has given it a conditional recommendation for the treatment of women with IBS-D based on moderate-quality evidence. Due to the risk for severe constipation and ischemic colitis, prescribers must be enrolled in an FDA-mandated risk evaluation and mitigation strategy program in order to prescribe alosetron.

Other medications with clinical evidence for the treatment of IBS-D include loperamide, antispasmodics, and tricyclic antidepressants. The AGA has given a conditional recommendation for loperamide use in patients with IBS-D. Although loperamide has not demonstrated global relief of IBS-D symptoms, this recommendation is based on its ability to reduce stool frequency in other diarrheal conditions, as well as its low cost, favorable safety profile, and wide availability. Antispasmodics (for example, cimetropium-dicyclomine, peppermint oil, pinaverium, and trimebutine) decreased abdominal pain and global symptoms of IBS in a meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials. Although the overall quality of studies was low, the AGA gave a conditional recommendation for the use of antispasmodics in IBS-D. Based on data from several randomized trials, tricyclic antidepressants offer modest relief of the abdominal pain and global symptoms of IBS-D. The AGA has given a conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence for the use of tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of IBS-D.

Management of Patients with Indeterminate Abdominal Pain

When abdominal pain is the primary symptom and is unrelated to food intake and defecation, centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome (CAPS) should be considered. Abdominal pain is described as constant, nearly constant, or frequently recurring. The pain is not localized and may include extraintestinal symptoms such as musculoskeletal pain. It can be associated with impairment in activities of daily living and psychosocial issues. CAPS is a result of central sensitization with disinhibition of pain signals. Limited evaluation is needed in the setting of chronic pain meeting the diagnostic criteria for CAPS. Initial evaluation should include a detailed medical and psychosocial history, physical examination, and limited laboratory studies to exclude gastrointestinal bleeding and inflammation.

Successful treatment depends on the patient-physician relationship, and should focus on setting appropriate goals and expectations. A combination of pharmacologic and/or psychological therapies may be needed, including tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Four classes of psychotherapy have shown benefits in CAPS when combined with medical therapy: cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy, mindfulness- and acceptance-based therapy, and hypnotherapy.

Narcotic bowel syndrome, also known as opiate-induced gastrointestinal hyperalgesia, is characterized by the paradoxical increase in abdominal pain with increasing doses of narcotics despite clinical evidence showing improvement or stability of the underlying condition. Often these patients fear tapering off narcotics and believe the narcotics are “the only thing that helps.” The only treatment is complete detoxification and cessation of narcotic use, which requires a trusting patient-physician relationship and understanding of the pathophysiology of the pain. Enrollment in a supervised detoxification program is recommended.

Diverticular Disease

A diverticulum is the herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through a weakness in the muscle wall. Diverticulosis (the presence of diverticula) is the most common finding identified during colonoscopy. Most patients with diverticulosis are asymptomatic, but 15% will develop complications. The causative mechanism is thought to be multifactorial, involving diet, microbiota, genetics, and colonic motility. The incidence of diverticulosis continues to rise in the Western world and increases with age, with a reported prevalence of 80% in persons aged 85 years and older. Diverticulosis may also cause bleeding, more commonly in the right colon, which often resolves spontaneously.

Diverticulitis is the consequence of a diverticulum becoming blocked, trapping bacteria, and subsequently developing inflammation. Diverticulitis can be classified as uncomplicated or complicated. In some patients, a focal area of colitis can develop in a segment of diverticulosis, called segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis.

The clinical presentation of uncomplicated diverticulitis is colicky abdominal pain that is relieved with flatus or a bowel movement. On physical examination, left-lower-quadrant abdominal tenderness is often present. Patients with complicated diverticulitis may present with dysuria, urinary frequency, pneumaturia, fecaluria, and recurrent urinary infection concerning for colovesical fistula. It is uncommon for patients with diverticulitis to present with rectal bleeding.

Acute diverticulitis is often a clinical diagnosis, usually not requiring imaging. However, a CT scan will help to differentiate uncomplicated from complicated diverticulitis.

The medical management of diverticulitis is based on the degree of the patient's symptoms and severity of diverticular disease. Uncomplicated diverticulitis is treated with oral antibiotics (ciprofloxacin or metronidazole) and a liquid diet. Intravenous antibiotics and hospitalization are required in patients unable to tolerate an oral diet; patients with severe comorbidities, advanced age, or immunosuppression; and patients for whom oral antibiotics have been ineffective.

Treatment of complicated diverticulitis depends on the severity of illness and CT findings. If the CT scan shows a large (>5 cm) abscess, CT-guided drainage may be needed. Surgery is indicated for patients presenting with, or who develop, peritonitis or persistent sepsis.

A high-fiber diet is recommended to prevent recurrence of diverticulitis. There is no evidence supporting restriction of foods such as nuts, berries, and seeds to prevent recurrent diverticulitis.

According to the American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the Management of Acute Diverticulitis, patients with a recent episode of acute diverticulitis should undergo colonoscopy 4 to 8 weeks after an episode of acute diverticulitis. Follow-up colonoscopy may identify a few cases of colorectal carcinoma. The risk for perforation after a case of diverticulitis is uncertain. The technical review estimated that 1 in 67 patients with confirmed acute diverticulitis would have a misdiagnosed colorectal cancer found on follow-up colonoscopy. Almost all of the misdiagnosed colorectal cancers included in the technical review were located in the area of diverticulitis. Assessing the patient for underlying inflammatory bowel disease is another reason for performing follow-up colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy during the acute phase of illness is contraindicated because acute diverticulitis causes acute colonic inflammation, which may increase the risk for perforation. The risk for perforation has been reported to be as high as 0.3%, but it is generally thought to be less than 0.1%, based on data from large populations undergoing screening colonoscopy. If the results of colonoscopy performed within the past 12 to 24 months are negative, then repeat colonoscopy is not needed.

Ischemic Bowel Disease

Ischemic bowel disease is a broad term describing a decrease in blood flow to the small or large intestine, which is insufficient to meet intestinal cellular metabolic function. It represents a spectrum of conditions that can be related to acute or chronic alterations of arterial or venous intestinal blood flow. Ischemic bowel disease can be broadly subcategorized into three major clinical syndromes: acute mesenteric ischemia, chronic mesenteric ischemia, and colonic ischemia.

Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

Clinical Features

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a rare condition caused by an abrupt decrease in blood flow to the small intestine that can be obstructive or nonobstructive in nature. Obstructive causes of AMI include emboli from a cardiac source (such as atrial or ventricular thrombus) or thrombosis related to underlying atherosclerotic disease. Nonobstructive AMI is most commonly caused by vasoconstriction of the mesenteric vasculature in the setting of severe sepsis or marked reduction in effective circulating volume (low-flow states). Mesenteric vein thrombosis may cause AMI and often is associated with malignancy, hypercoagulable states, or intra-abdominal inflammatory conditions. If the reduction of blood flow is prolonged, bowel infarction occurs, which is the most important prognostic factor for adverse outcome.

AMI most commonly presents with abrupt onset of severe, periumbilical abdominal pain followed by the urge to defecate. The abdominal pain is constant and the patient may subsequently have loose, nonbloody stools. Hematochezia occurs in a minority of cases of AMI (15%) and its presence signifies concomitant right colon ischemia. In the early course of AMI, the abdominal examination may be falsely reassuring: despite the patient's reporting severe abdominal pain, the physical examination reveals a soft, nontender, nondistended abdomen without peritoneal signs. This is called “pain out of proportion to physical examination findings” and should immediately raise suspicion for early AMI. With delayed or late presentation, intestinal ischemia progresses to infarction and peritoneal signs develop. This represents late AMI, which carries a high mortality rate.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies and abdominal imaging findings in the early course of AMI, before the development of intestinal infarction, are nonspecific. Most patients with AMI will have elevated leukocyte counts. A serum lactate concentration may be normal, and this should not exclude the diagnosis.

CT angiography is the recommended method of imaging for the diagnosis of AMI. CT angiography depicts the vessel origins and length of vessels, and characterizes the occlusion. While MR angiography avoids the risks of radiation and contrast exposure, it takes longer and is less sensitive for distal and nonocclusive disease. Duplex ultrasonography is an effective, low-cost method to assess the proximal mesenteric vessels, but an adequate ultrasound examination often cannot be performed in patients with AMI. The classic angiographic finding in obstructive AMI is either an embolus or thrombus in the superior mesenteric artery.

Treatment

After aggressive resuscitation and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, angiography with selective catheterization of the mesenteric vessels is indicated. Findings signifying mesenteric infarction, such as pneumatosis intestinalis (presence of gas within the wall of the intestine) or portal venous gas, require emergent surgery.

Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia

Clinical Features

Chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) is an uncommon condition that involves a gradual decrease in blood flow to the small intestine over months to years. It most commonly results from atherosclerotic narrowing of the mesenteric arteries. CMI occurs when two of the three adjacent mesenteric vessels (celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric) are severely narrowed.

The classic symptom triad of CMI is postprandial abdominal pain, sitophobia (fear of eating), and weight loss. However, this triad is seen in only 30% of patients with CMI, and CMI should be suspected in the setting of recurrent postprandial abdominal pain. The pain begins approximately 30 minutes after food ingestion and results from “shunting of blood” away from the small intestine to meet the increased functional demand of the stomach. Due to fixed narrowing of the mesenteric arteries, blood flow cannot increase sufficiently to meet the intestinal metabolic demand and ischemia results.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CMI requires symptoms (the CMI triad), exclusion of alternative causes of postprandial abdominal pain and weight loss, and compatible radiographic findings. Imaging modality should be chosen based on patient characteristics and availability. CT or MR angiogram findings suggestive of CMI include severe stenosis (>70%) of two of the three mesenteric arteries. If the patient has compatible symptoms and suggestive angiographic findings, and alternative explanations for postprandial abdominal pain have been excluded, then the diagnosis of CMI is secure.

Treatment

CMI is treated with percutaneous endovascular stenting or surgical revascularization. Choice of therapy depends on operative risk and occlusive lesion characteristics. Periprocedural morbidity and mortality are lower with endovascular stenting; however, it is less durable than surgical revascularization.

Colonic Ischemia

Colonic ischemia is the most common form of ischemic bowel disease. It most commonly results from a nonocclusive low-flow state in microvessels, which occurs in the setting of hypovolemia or hypotension. Risk factors include age (older than 60 years), female sex, vasoconstrictive medications, constipation, thrombophilia, and COPD.

Clinical Features

Colonic ischemia presents with the abrupt onset of lower abdominal discomfort that is mild to moderate and cramping, and is followed within 24 hours by hematochezia. The onset of bleeding often prompts the patient to seek medical attention.

Diagnosis

Physical examination most commonly reveals mild lower abdominal tenderness over the involved bowel segment without peritoneal signs. Laboratory studies may show a mild elevation in the leukocyte count and blood urea nitrogen level.

Abdominal CT is indicated to assess the severity, phase, and distribution of colonic ischemia. CT findings in colonic ischemia are nonspecific and include bowel-wall thickening (Figure 21) and pericolonic fat stranding (increase in density within the pericolonic fat secondary to inflammation). Infections that can mimic colonic ischemia, such as cytomegalovirus, C. difficile, and enterohemorrhagic E. coli, must be excluded. Colonoscopy with biopsy is the test of choice to confirm the diagnosis of colonic ischemia.

Because colonic ischemia is most commonly caused by a nonocclusive low-flow state, dedicated imaging of the mesenteric vasculature is of low yield and generally not indicated. The exception to this rule is right-sided colonic ischemia, which can be the harbinger of AMI caused by a focal thrombus or embolus of the superior mesenteric artery. Therefore, patients with right-sided colonic ischemia require noninvasive imaging of the mesenteric vasculature to exclude occlusive process of the superior mesenteric artery.

Treatment

Most cases of colonic ischemia are mild and transient with rapid spontaneous resolution. Patients with more severe disease require hospitalization for supportive care with bowel rest, restoration of intravascular volume, antimicrobial therapy in select cases, and close observation. Only a small percentage of patients require operative intervention for necrotic bowel or irreversible complications such as stricture.

Anorectal Disorders

Perianal Disorders

Perianal disorders can range from relatively common and benign disorders, such as hemorrhoids, to potentially disabling conditions, such as anal fissure or fecal incontinence, to the life-threatening condition of anal cancer. Perianal symptoms, including bright red blood per rectum, anal pain, anal itching, or a reported anal mass, should prompt a detailed evaluation of the anus, anal canal, and rectum that includes visual inspection of the anus and digital rectal examination. Further evaluation with anoscopy or proctoscopy may be required to establish the diagnosis. Colonoscopy is indicated when additional alarm features are present; these include age older than 50 years, altered bowel habits, anemia, IBD, unexplained weight loss, and/or family history of colorectal cancer.

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are submucosal, arteriovenous sinusoids that are part of normal anorectal anatomy and are believed to play an important role in anal canal function. Risk factors for symptomatic hemorrhoids include ascites, pregnancy, excessive sitting or squatting, systemic rheumatic disorders, low dietary-fiber intake, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle. Recurrent straining and persistent bowel alterations (either constipation or diarrhea) can lead to engorgement of hemorrhoid plexuses, causing symptoms of bleeding, prolapse, and swelling. Age-related changes can cause the hemorrhoid beds to slide back and forth during defecation, resulting in mucoid anal discharge, as well as perianal wetness, soiling, irritation, and/or pruritus. Pain is not a common symptom of uncomplicated hemorrhoids and should raise suspicion for hemorrhoid complications, including thrombosis, ischemia, or incarceration from prolapse, or for an alternative diagnosis such as anal fissure, perirectal infection, or perianal abscess. Other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis are perianal dermatitis, lichen sclerosis, condyloma, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, colorectal or anal polyps or cancer, and IBD. Hemorrhoids are categorized as internal if proximal to the dentate line, external if distal to the dentate line, or mixed if crossing the dentate line.

The evaluation of hemorrhoids should always include a careful perianal and digital rectal examination. Symptomatic hemorrhoids can be confused with rectal mucosal prolapse, full thickness rectal prolapse, or a prolapsed rectal polyp. The presence of prolapsed concentric folds indicates rectal prolapse as opposed to a prolapsed hemorrhoid or anal polyp (Figure 22). Further direct evaluation of the anorectum can be considered with anoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy.

First-line therapy for hemorrhoids includes increased fiber intake, adequate liquid intake, and avoidance of straining. Although various topical agents may reduce hemorrhoid symptoms, they are not necessary for curative therapy. Patients with internal hemorrhoids unresponsive to medical therapy should be considered for banding. Other options, including sclerotherapy and infrared coagulation, are less effective.

Thrombosed external hemorrhoids are best treated with surgical excision within 72 hours of symptom onset. Surgical hemorrhoidectomy should be reserved for refractory hemorrhoids, large external hemorrhoids, or combined internal and external hemorrhoids with rectal prolapse.

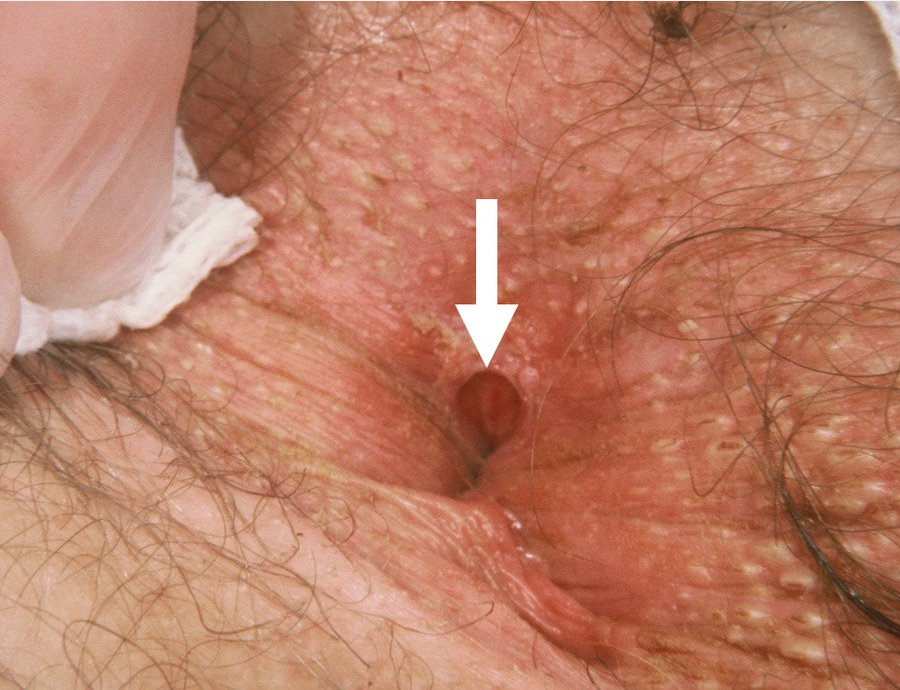

Anal Fissure

Anal fissures are longitudinal mucosal tears in the anal canal characterized by anorectal pain worsened by bowel movements and sitting (Figure 23). Rectal bleeding with bowel movements or wiping is frequently reported. Anal fissures are either idiopathic or the result of trauma due to the passage of hard stool, receptive anal intercourse, or the insertion of a foreign body such as an enema or endoscope. Anal fissures occurring laterally should raise concern for other entities including Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, tuberculosis, syphilis, HIV, psoriasis, or anal cancer. Anal fissures lasting more than 8 to 12 weeks are considered chronic and may be characterized by edema and fibrosis as well as the presence of a sentinel pile (appearing as a skin tag) or hypertrophied anal papilla within the anal canal.

Anal fissures are painful longitudinal mucosal tears in the anal canal.

Anal fissures are painful longitudinal mucosal tears in the anal canal.

Acute anal fissures generally resolve within a few weeks with the use of sitz baths, psyllium, and bulking agents. Topical anesthetics and anti-inflammatory agents can be considered to address pain or bleeding, but their use is not required to promote fissure healing. Rectal spasm is the major reason for anal fissures becoming chronic and should be treated with either topical calcium channel blockers or nitrates. Patients with chronic fissures unresponsive to these measures should be referred for internal sphincter botulinum toxin injection or surgical sphincterotomy.

Further evaluation is indicated for patients with the following:

- Anal fissures with atypical features: eccentrically located (lateral, anterior), multiple, painless, very deep, recurrent

- Rectal bleeding: requires sigmoidoscopy if age <50 and colonoscopy if age ≥50

- Failure to respond after 8 weeks of optimal medical therapy, including topical vasodilators (eg, nitroglycerin, nifedipine), stool softeners, and advice to supplement fiber intake In patients with Crohn disease, anal fissures most frequently (80%) present as posterior midline fissures but can present atypically (eg, eccentric location) in 20% of cases. Complications include fistula and abscess formation. Therefore, patients such as this one with with nonhealing or atypical anal fissures require a colonoscopy and small-bowel imaging to rule out Crohn disease.

Fecal Incontinence

Fecal incontinence, also called accidental bowel leakage, is defined as the recurrent, uncontrolled passage of fecal material of at least 3 months' duration. Fecal incontinence does not include the passage of clear mucus or flatus incontinence. Fecal incontinence is grossly underreported due to associated embarrassment, and health care providers should inquire about it during clinic visits, particularly in patients at risk. Fecal incontinence is more common in multiparous women and in patients with advanced age, obesity, diarrhea or urinary incontinence, or history of obstetric complications, anorectal surgery or anorectal disease. Various factors can contribute to fecal incontinence, including loose stool, impairment of rectal storage capacity, altered rectal sensation, and reduced anal sphincter tone. Constipation with resultant fecal loading and overflow diarrhea can also cause fecal incontinence.

A digital rectal examination is essential in the evaluation. This can identify reduced anal sphincter tone, prolapse of hemorrhoids or rectum, or rectal stool impaction. Additional diagnostic testing is determined by the history and rectal examination. If fecal loading is suspected, an abdominal radiograph can be diagnostic. If diarrhea is present, stool testing and/or colonoscopy should be considered. If weak sphincter tone is appreciated or rectal urgency is reported, evaluation may include anorectal manometry to assess anal sphincter pressure and rectal sensation, anal endosonography for anal sphincter defects, or defecography for structural evaluation of the pelvic floor.

Initial treatment should be directed at the treatment of reversible factors such as diarrhea, constipation, offending medications, smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity. Effective dietary modifications include fiber supplementation and avoidance of trigger foods. If there is lack of response to conservative measures, the next step is pelvic floor muscle training with specially trained physical therapists. In the event of lack of response to biofeedback therapy, other treatment options include the use of anal plugs, anal wicking, various minimally invasive procedures (for example, the use of injectable bulking agents or sacral nerve stimulation), or surgery such as sphincteroplasty.

Anal Cancer

Anal cancer (Figure 24) is rare, with a yearly incidence of 8000 cases in the United States. Squamous cell cancer is the most common type, representing 80% of all anal cancers. The incidence has been rising by 2.2% each year for the last decade. Delayed diagnosis by up to 2 years in more than half of cases has resulted in increased need for aggressive surgical intervention.