Disorders of the Pancreas

- related: GI

- tags: #GI

Acute Pancreatitis

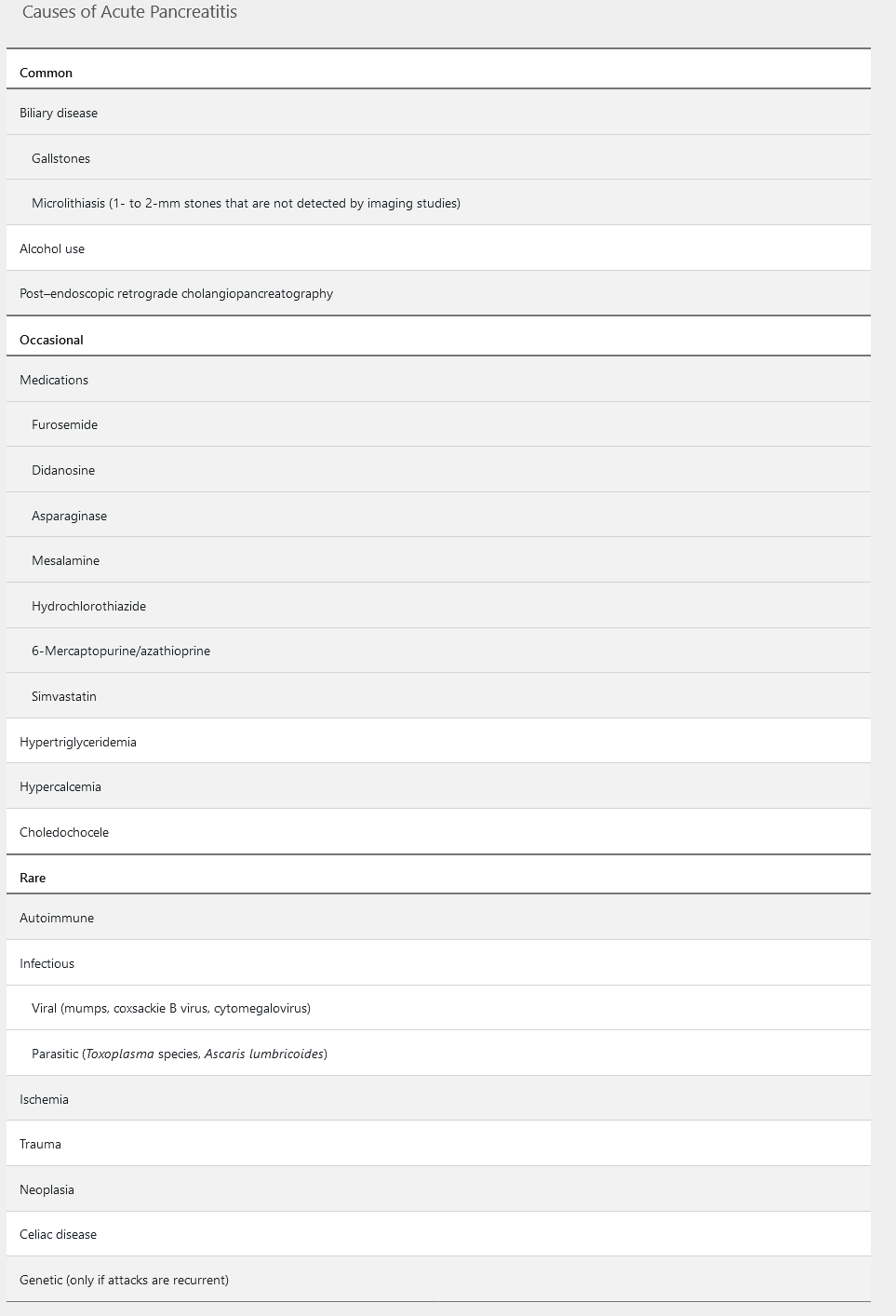

Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory process involving the pancreas and extrapancreatic organs. It is the most common gastrointestinal cause of hospitalization in the United States. Passage of gallstones, sludge, or biliary crystals (microlithiasis) is the most common cause of acute pancreatitis (Table 15). Premature activation of digestive enzymes and release of cytokines cause “autodigestion” of the pancreas and inflammation, which may involve surrounding tissues and distant organs.

Acute pancreatitis is classified as mild, moderately severe, or severe. Mild acute pancreatitis does not involve organ failure or local or systemic complications, usually resolves within 1 week, and has a low mortality rate. Twenty percent of patients with acute pancreatitis develop moderately severe or severe disease. Moderately severe acute pancreatitis involves local or systemic complications such as necrosis or transient organ failure (for less than 48 hours). Severe acute pancreatitis involves systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), persistent organ failure (usually kidney or respiratory failure), duration longer than 48 hours, and one or more local complications; it has a mortality rate as high as 50%.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

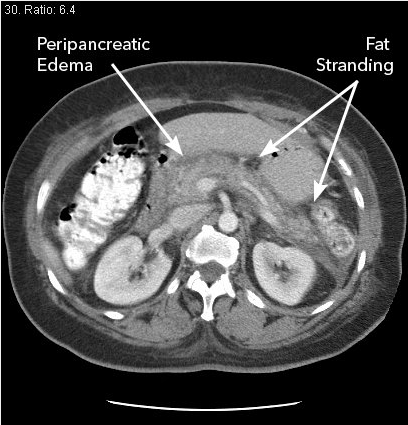

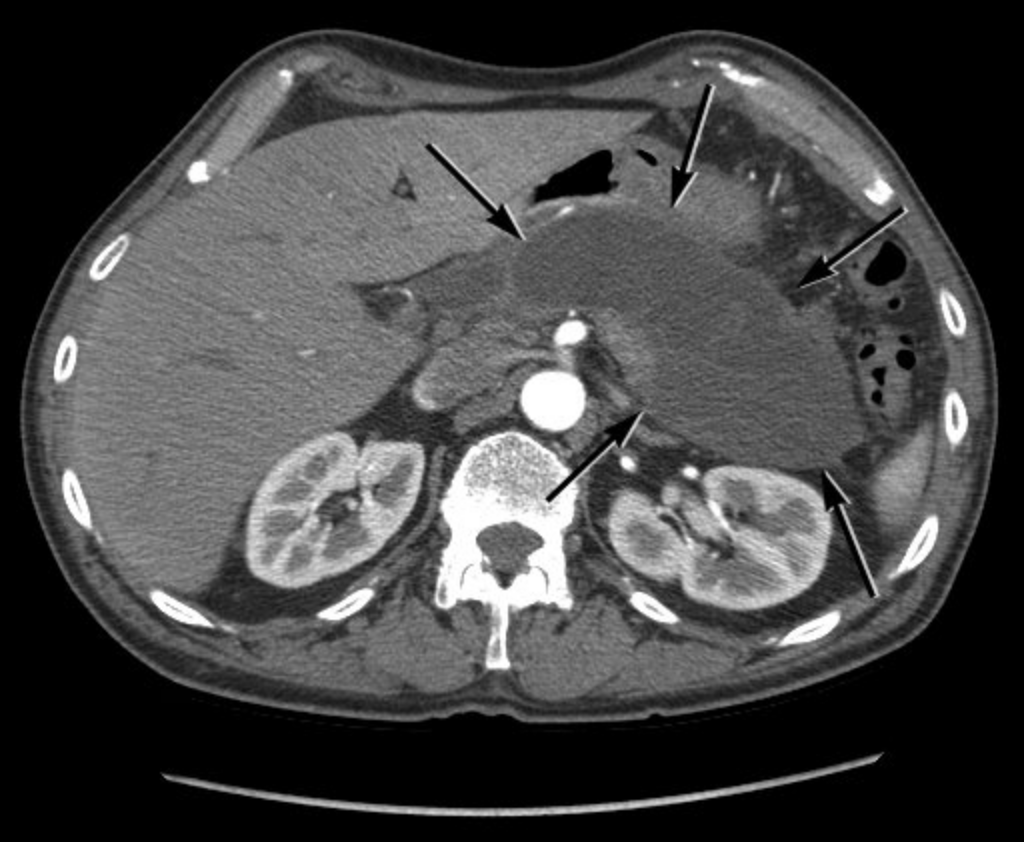

The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires two of the following three criteria: (1) acute-onset abdominal pain characteristic of pancreatitis (severe, persistent for hours to days, and epigastric in location, often radiating to the back); (2) serum lipase or amylase levels elevated to three to five times the upper limit of normal; and (3) characteristic radiographic findings on contrast-enhanced CT (Figure 9), MRI, or transabdominal ultrasonography. The presence of high fever and leukocytosis is part of the cytokine cascade and does not necessarily indicate infection.

Because acute pancreatitis is most commonly caused by biliary disorders, patients with acute pancreatitis should undergo transabdominal ultrasonography. Transabdominal ultrasonography is preferred over CT because it has a higher sensitivity for detection of gallstones, avoids the risks associated with intravenous contrast, and is more cost effective. However, abdominal air can limit the visualization of the pancreas in patients with acute pancreatitis. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may be considered in patients who do not have abnormal findings on ultrasonography. CT may be indicated if the diagnosis is in question or if clinical symptoms are not alleviated within the first 48 hours.

Acute liver-enzyme elevation at presentation suggests biliary obstruction. Serum amylase and lipase levels may be elevated in conditions other than acute pancreatitis, such as kidney disease, acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, intestinal obstruction or ischemia, peptic ulcer, or gynecologic disorders. Enzyme levels may be falsely low or normal in patients with hypertriglyceride-induced pancreatitis because of lipemic-serum interference with laboratory assays. Triglyceride levels should be measured in patients without a biliary cause of acute pancreatitis, and if the triglyceride level is greater than 1000 mg/dL (11.3 mmol/L), it can be considered the cause of the acute pancreatitis.

Prognostic Criteria

Risk factors for severe disease include age older than 55 years, medical comorbidities, BMI greater than 30, the presence of SIRS, signs of hypovolemia on presentation (for example, a serum blood urea nitrogen level greater than 20 mg/dL [7.1 mmol/L] and rising, a hematocrit greater than 44%, or an elevated serum creatinine), the presence of pleural effusions and/or infiltrates, and altered mental status. A systematic review of 18 multiple-factor scoring systems, including the Ranson criteria and the Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, for predicting outcome in acute pancreatitis found these systems to have limited clinical value and accuracy. Scoring systems only identify severe disease as it develops, without enough lead time for intervention, and they are too cumbersome for routine use. Data suggest serum hematocrit, elevated blood urea nitrogen levels, and the presence of SIRS to be as accurate as complex scoring systems in predicting outcome, and they are easier to use.

Management

Mainstays of management include fluid resuscitation, pain management, and antinausea medication.

Aggressive hydration (250-500 mL/h of intravenous lactated Ringer solution) should be given to patients with acute pancreatitis on presentation and is most beneficial in the first 12 to 24 hours. More rapid fluid resuscitation (boluses) may be needed in patients with severe volume depletion. Patients with organ failure or SIRS should be admitted to an ICU or intermediary care setting, with reassessment of fluid requirements every 6 hours for the first 24 to 48 hours.

Routine use of antibiotics is not warranted in acute pancreatitis, unless there is evidence of extrapancreatic infection, such as ascending cholangitis, bacteremia, urinary tract infection, or pneumonia. Use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with sterile pancreatic necrosis to prevent infected necrosis is not recommended.

In mild acute pancreatitis, oral feedings can be started as soon as nausea and vomiting are controlled and clinical symptoms begin to subside. Enteral feeding should begin within 72 hours if oral feeding is not tolerated; it is usually required in patients with moderately severe or severe acute pancreatitis. Feeding with a nasojejunal tube has traditionally been preferred, but data suggest that nasogastric feedings are likely equally effective and easier to administer. Enteral feeding promotes a healthy gut-mucosal barrier to prevent translocation of bacteria into inflamed tissues.

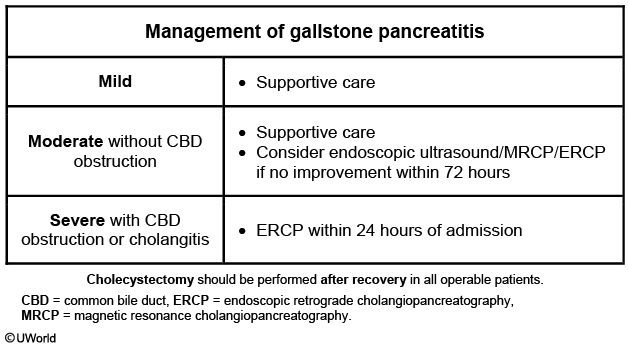

If a biliary cause of acute pancreatitis is suspected, serial liver chemistry tests and clinical symptoms can show whether the biliary obstruction is ongoing or resolving. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is not indicated in patients with gallstone pancreatitis unless there is persistent elevation of liver chemistries or if choledocholithiasis is seen on imaging studies. Patients with cholangitis should undergo urgent ERCP. Patients with uncomplicated gallstone pancreatitis should be considered for cholecystectomy before discharge.

There is no value in rechecking serum amylase and lipase levels after the diagnosis is established.

Patients with mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis should receive supportive care (eg, analgesics, intravenous fluids) as most stones pass into the duodenum. However, patients with evidence of common bile duct obstruction or acute cholangitis can benefit from urgent (<24 hours) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy, as this has been shown to reduce disease severity.

Complications

There are two overlapping phases of acute pancreatitis with two peaks in mortality. The early phase is the first week of the disease, when the body is responding to local pancreatic injury and the cytokine cascade, and SIRS and organ failure are possible. The late phase occurs after the first week and may persist for weeks to months in patients with moderately severe or severe acute pancreatitis. Significant risk for infection in peripancreatic fluid collections and necrosis occurs in the late phase.

Proper classification of fluid collections in acute pancreatitis is important to guide management. An international consensus group updated the Atlanta classification and definitions of acute pancreatitis and its complications in 2012 to try to promote consistency in diagnosis and management. Four types of fluid collections were defined:

-

Acute peripancreatic fluid collections are collections that occur in edematous interstitial pancreatitis (no necrosis) within the first 4 weeks, are thought to occur because of rupture of main or side branch ducts as a result of inflammation, are sterile, and usually resolve spontaneously.

-

Pancreatic pseudocysts are acute peripancreatic fluid collections that have persisted for longer than 4 weeks, developed a well-defined wall, and contain no solid debris (necrosis).

-

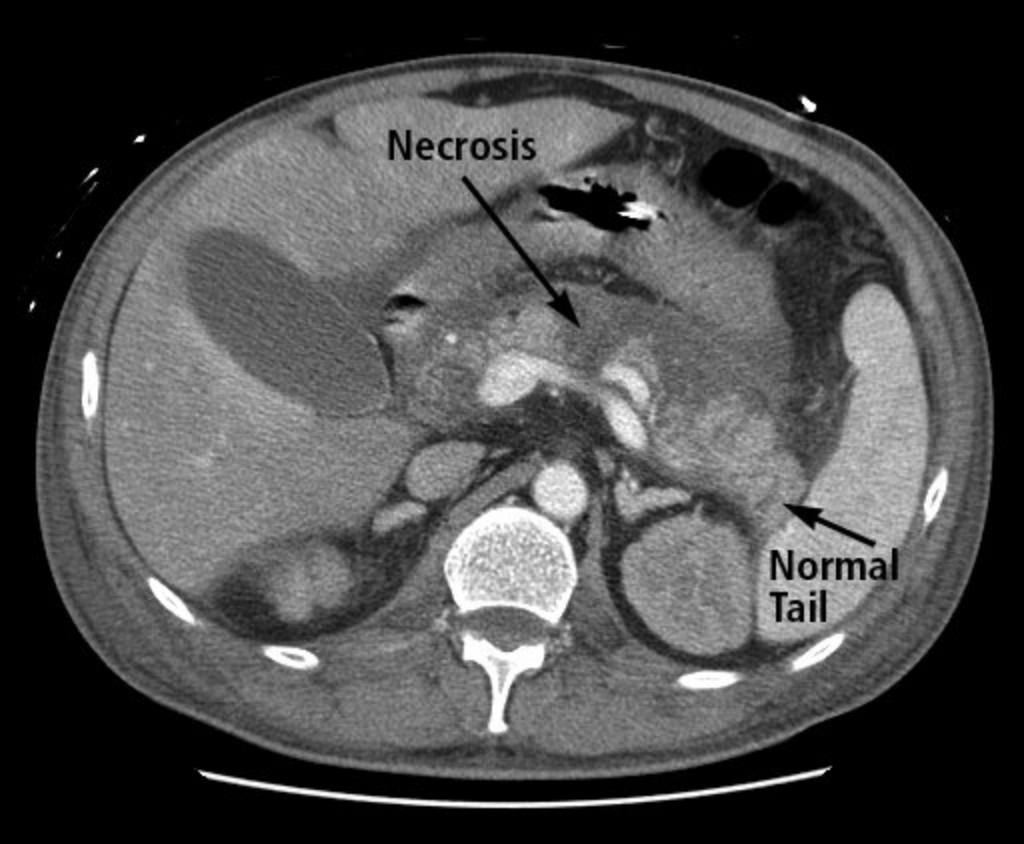

Acute necrotic collections (Figure 10) are areas of necrosis in the pancreatic parenchyma and/or peripancreatic tissues within the first 4 weeks of acute pancreatitis.

-

Walled-off necrosis (Figure 11) occurs after 4 weeks, when the body liquifies the necrosis and contains it within a well-defined wall.

CT scan showing acute pancreatitis with hypoperfusion of the body of the pancreas as indicated by lack of enhancement following intravenous contrast infusion (necrosis) and normal perfusion of the pancreatic tail.

CT scan showing acute pancreatitis with hypoperfusion of the body of the pancreas as indicated by lack of enhancement following intravenous contrast infusion (necrosis) and normal perfusion of the pancreatic tail.

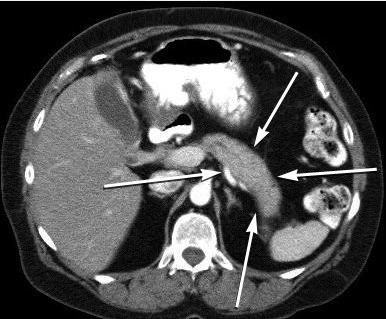

CT scan showing maturation and liquefaction of pancreas necrosis of nearly the entire pancreas over 4 weeks in duration with a well-defined rim or wall (arrows), known as walled-off necrosis.

CT scan showing maturation and liquefaction of pancreas necrosis of nearly the entire pancreas over 4 weeks in duration with a well-defined rim or wall (arrows), known as walled-off necrosis.

Contrast-enhanced CT may not be able to distinguish solid from liquid content in fluid collections; therefore, necrotic collections are frequently misdiagnosed as pancreatic pseudocysts. Pancreatic pseudocysts do not require drainage unless they cause significant symptoms, regardless of size. Because they contain only fluid, pseudocysts are easily drained under endoscopic or radiographic guidance. Walled-off necrosis is not as amenable to percutaneous or endoscopic drainage due to solid necrotic debris within the cavity and may require endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical debridement.

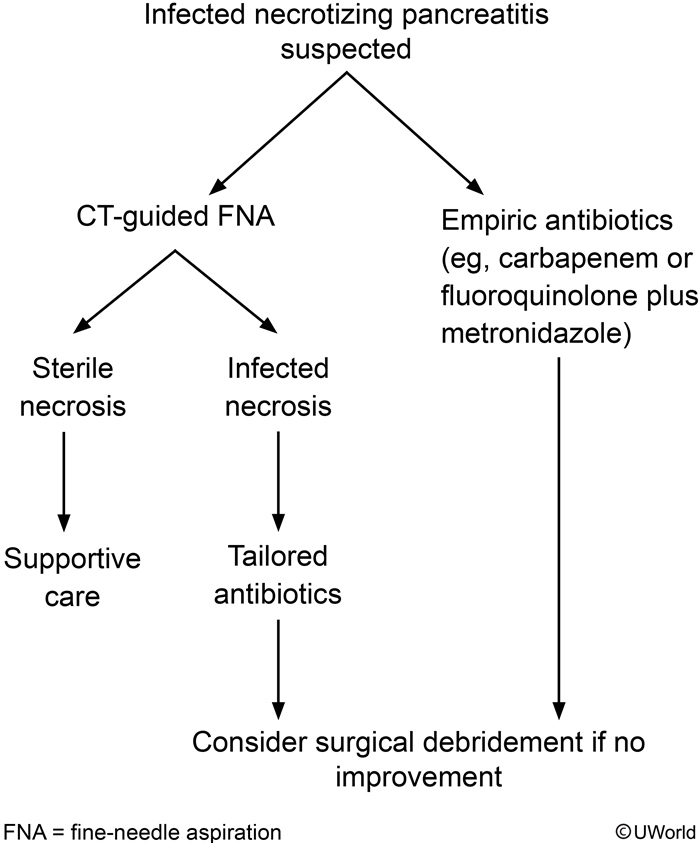

The management of suspected infected necrosis includes initiation of antibiotics (for example, imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem, or ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole) with consideration of fine-needle aspiration with Gram stain and culture under CT guidance. Drainage procedures or debridement should be delayed for at least 4 weeks if possible to allow encapsulation of the necrosis with a fibrous wall.

Infected necrosis occurs in one-third of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and should be suspected in those who do not improve or who deteriorate clinically after a week of hospitalization.

These patients may either be treated with empiric antibiotics or first undergo CT-guided aspiration with Gram stain and culture to direct antimicrobial therapy. Carbapenems (eg, imipenem, meropenem) or a combination of a quinolone and metronidazole is a recommended empiric regimen due to the coverage of gut-derived organisms and superior penetration into the pancreatic tissue. Patients who fail to respond to antibiotics may require percutaneous or open surgical debridement of infected necrosis (eg, necrosectomy).

Pseudocyst

Persistently elevated lipase and abdominal fullness following a resolved attack of acute pancreatitis suggest pancreatic pseudocyst. Pancreatic pseudocysts are more common in alcoholic than non-alcoholic pancreatitis and usually occur 4-6 weeks after the initial pancreatitis episode. About 10% of patients with acute pancreatitis and 30%-40% with chronic pancreatitis develop pseudocysts.

Patients may be asymptomatic or present with abdominal pain or fullness. Fever indicates infected pseudocyst. Pseudocyst expansion can result in gastric outlet or biliary obstruction, vascular occlusion, or fistula formation into adjacent viscera (eg, pleura). Serum lipase usually increases within 4-8 hours of acute pancreatitis, peaks at 24 hours, and returns to normal within 8-14 days. Lipase levels are not necessary for monitoring the course of pancreatitis, but persistent elevation can indicate complications (eg, pancreatic duct blockage, pseudocyst) in symptomatic patients. In contrast, chronic pancreatitis usually have normal or mildly elevated lipase.

Diagnosis is confirmed via abdominal computed tomography scan showing a thick-walled, rounded, fluid-filled mass adjacent to the pancreas. Endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration can help differentiate pancreatic pseudocyst from other cystic pancreatic lesions. Most pseudocysts resolve spontaneously, and asymptomatic cysts do not require intervention. Symptomatic or complicated pseudocysts (infection, duodenal or biliary obstruction) can be drained via percutaneous, surgical, or endoscopic procedures (preferred).

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is thought to develop when the inflammatory response to acute pancreatitis persists and ongoing inflammation activates stellate cells, resulting in a fibro-inflammatory response. This causes distorted tissue architecture, loss of normal parenchyma, activation of pancreatic nociceptors, and loss of acinar and islet cell function. Genetic variants affecting inflammatory response, enzyme activation, and tissue repair are thought to play important roles in the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis. Many genes have been identified as disease modifiers in chronic pancreatitis, but the gene-environment interaction is not fully understood.

Alcohol use has long been described as a risk factor for chronic pancreatitis, but less than 3% of heavy alcohol users develop pancreatic disease. Patients who drink more than five drinks per day (or 35 drinks per week) seem to be more susceptible to chronic pancreatitis. In the largest study of patients with chronic pancreatitis in North America, only 46% had a history of significant alcohol use. The higher prevalence of alcohol-associated pancreatitis among men could be partially explained by an X chromosome–linked genetic variant, the CLDN2 gene. Tobacco is considered an independent risk factor. Table 16 lists common causes of chronic pancreatitis.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom of chronic pancreatitis (seen in 85% of patients), but some patients have no pain. Pain patterns can vary from constant, daily pain to intermittent attacks of severe pain. Pancreatic enzyme levels may not increase during attacks of pain because of fibrosis and atrophy of acinar cells and decreased enzyme production. Constant daily pain in chronic pancreatitis causes significant reduction in quality of life, with increased use of health care resources, disability benefits, and time away from employment. Exocrine or endocrine insufficiency occurs in some patients as a result of significant tissue destruction.

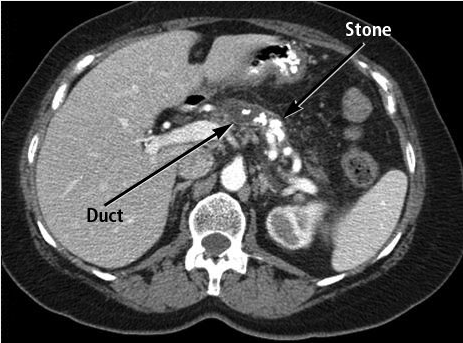

Diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis remains challenging because hallmark anatomic features, such as pancreatic calcifications (Figure 12), only occur in 25% of patients, and other features of atrophy or duct dilation can occur normally with aging or other disease processes. Imaging with CT or MRI is the initial test of choice. In the setting of high clinical suspicion and negative findings on imaging, endoscopic ultrasonography and secretin-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography may be useful as second- and third-line tests; pancreatic biopsy may rarely be necessary. ERCP is no longer used as a diagnostic tool for chronic pancreatitis. Genetic testing for cystic fibrosis and familial pancreatitis should be considered in younger patients. Pancreatic exocrine function may be assessed with fecal elastase testing, which has largely replaced fecal fat testing.

CT scan showing chronic calcific pancreatitis with multiple stones in the main duct and side branches of the pancreas.

CT scan showing chronic calcific pancreatitis with multiple stones in the main duct and side branches of the pancreas.

Management

The management of chronic pancreatitis focuses on treating symptoms. No effective treatment exists to reverse or halt disease progression. Patients should be counseled to avoid alcohol and tobacco, as this may lessen attacks of inflammation and pain. Intermittent attacks of severe acute pain are treated as in acute pancreatitis. Complications of chronic pancreatitis, including pseudocyst, pancreatic duct stones causing upstream obstruction, and malignancy, should be evaluated with imaging when a patient's symptom pattern changes. Endoscopic techniques are first-line therapy for relief of ductal obstruction. Constant, daily pain is more challenging to manage and frequently involves the use of medications such as tramadol, gabapentinoids, and possibly narcotics, although long-term use of narcotics should be avoided due to hyperesthesia and development of tolerance or addiction. Pancreatic enzymes are used to treat steatorrhea but have not been shown to effectively treat pain or prevent attacks of pancreatitis. Two large randomized trials using antioxidants to treat chronic pancreatitis pain showed conflicting results; guidelines suggest that antioxidants be considered, although it is unclear which antioxidants and doses are appropriate. Nerve blocks and neurolysis procedures are also guideline-recommended; however, the response rate is low and pain relief, if achieved, only lasts a few weeks.

Surgery offers the best long-term results for chronic, refractory pain management and, depending on anatomy and cause, may include lateral pancreaticojejunostomy, duodenal-preserving pancreatic head resection, pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, or even total pancreatectomy with or without auto–islet cell transplantation. These procedures have been shown to improve outcomes in patients at high-volume pancreas referral centers. Pancreatic endocrine insufficiency may require specialty referral for labile diabetes management and nutritional consultation.

Autoimmune Pancreatitis and IgG4 Disease

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a frequent manifestation of IgG4-related disease. Other organs that can be affected include the lacrimal and salivary glands, central nervous system, kidneys, thyroid gland, lungs, biliary tract and liver, prostate gland, retroperitoneum, and lymph nodes. Storiform fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis are characteristics seen in the pancreas and biliary tract. The most common pancreatic manifestation of IgG4-related disease is type 1 AIP, with abundant infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and lymphocytes. Type 2 AIP has no or few IgG4-positive cells but is characterized by idiopathic duct-centric neutrophil infiltration, known as a granulocytic epithelial lesion. Type 2 AIP is a pancreas-specific disease with occasional association with ulcerative colitis. The 2011 International Consensus of Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Pancreatitis endorsed the concept of type 1 and type 2 disease, but there is some debate over whether type 2 should be considered an IgG4-related disease.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria for AIP require image findings of a narrowed main pancreatic duct and parenchymal swelling (the “sausage-shaped” pancreas Figure 13 and response to glucocorticoids. Patients with type 1 AIP have elevated levels of IgG4-positive cells in pancreatic tissue (>10 IgG4-positive cells/hpf), and 60% to 80% of patients have associated sclerosing cholangitis, sclerosing sialoadenitis, or retroperitoneal fibrosis. A significant elevation of serum IgG4 level is helpful in diagnosing type 1 AIP. Patients with type 2 AIP will have no elevation of IgG4-positive cells in pancreatic tissue. Patients with both types may present with abdominal pain or obstructive jaundice with or without a mass. In patients presenting with obstructive jaundice or with a mass, pancreatic malignancy must be considered. Many patients with malignancy have a dilated upstream main pancreatic duct, whereas patients with AIP may have a narrow main duct. Endoscopic ultrasonography and biopsy may be required to differentiate AIP and pancreas neoplasm. Ten percent of patients with type 1 AIP may develop chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic stone formation.

CT scan showing the homogeneous, hypodense “sausage-shaped” swelling (arrows) seen in autoimmune pancreatitis.

CT scan showing the homogeneous, hypodense “sausage-shaped” swelling (arrows) seen in autoimmune pancreatitis.

Treatment

Glucocorticoids are effective treatment for types 1 and 2 AIP, starting with oral prednisolone, 0.6 to 1.0 mg/kg/d, and tapered over 2 to 3 months. Response is determined by symptom relief and imaging features. Failure of clinical symptoms to respond to glucocorticoids suggests an incorrect diagnosis, and other causes should be investigated. Up to 60% of patients may relapse. Readministration of glucocorticoids or immunomodulators, such as 6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, mycophenolate, or rituximab, may be used to treat recurrent AIP.

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma has a poor prognosis and increasing incidence. In 2015, there were approximately 49,000 cases diagnosed in the United States and 41,000 deaths. It is predicted to become the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States over the next decade, with an overall 5-year survival rate of less than 6%.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer include age older than 50 years, smoking history, obesity, chronic pancreatitis, and mucinous cystic lesions of the pancreas. Inherited conditions associated with pancreatic cancer include Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, BRCA2 germline mutations, hereditary pancreatitis, familial atypical multiple mole melanoma, Lynch syndrome, and familial pancreatic cancer with at least two affected first-degree relatives.

Clinicians should not screen average-risk individuals for pancreatic cancer. The American Gastroenterological Association and the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Consortium recommend that clinicians screen select high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer, including those with a genetic predisposition to disease. If possible, screening should be performed at a center experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma include abdominal pain, back pain, weight loss, and jaundice if the lesion is located in the head of the pancreas obstructing the common bile duct. Pancreatic cancer is highly associated with diabetes mellitus, and two thirds of patients develop new-onset diabetes mellitus in the 36 months surrounding the diagnosis. Venous thromboembolic events and depression have been observed to occur at higher rates in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma than in patients with other malignancies.

Diagnosis

Pancreas protocol CT uses multiphasic arterial and venous phases with thin cuts (3 mm) through the abdomen to view the primary tumor's relationship to mesenteric vasculature and to detect metastatic lesions. Some studies suggest that pancreas protocol MRI may be superior to CT for pancreatic disease. Histopathologic confirmation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma is increasingly recommended before initiation of therapy. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy is preferable to CT-guided biopsy in patients with potentially resectable disease because of ultrasonography's higher diagnostic yield, safety, and lower risk for peritoneal seeding. Patients are considered for primary surgical resection if they have no involvement of mesenteric vasculature or metastatic disease and are healthy enough for major intra-abdominal surgery. Preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may be recommended for patients with locally advanced disease.

Ampullary Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater accounts for 0.2% of gastrointestinal malignancies and usually presents early because of obstruction of the biliary system. Endoscopic ultrasonography with biopsy is the preferred method for staging and tissue diagnosis, with 90% accuracy. At least 50% of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome develop adenomatous changes of the periampullary region; upper endoscopy screening in patients with this syndrome should begin at age 25 to 30 years. See Colorectal Neoplasia for more information on adenomatous polyposis syndromes.

Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas

Pancreatic cysts are found incidentally in 15% of patients undergoing abdominal imaging. The detection of a cystic lesion in the pancreas causes anxiety in patients and clinicians and is a growing driver of health care use in the United States.

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are subcategorized as mucin-producing and non–mucin-producing cysts. Mucin-producing cysts are thought to have malignant potential, but most never become malignant. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are the most commonly found cystic lesions of the pancreas. Most IPMNs arise from a branched duct and have a very low rate of malignant transformation. In contrast, the rate of malignant transformation is greater than 65% in IPMNs involving the main pancreatic duct (Figure 14). Other high-risk features are the presence of symptoms, cyst size greater than 3 cm, and a solid component to the cyst. Main-duct IPMNs can be diagnosed based on diffuse dilation of the main pancreatic duct and the characteristic feature of mucin exuding from the ampulla during endoscopic visualization.

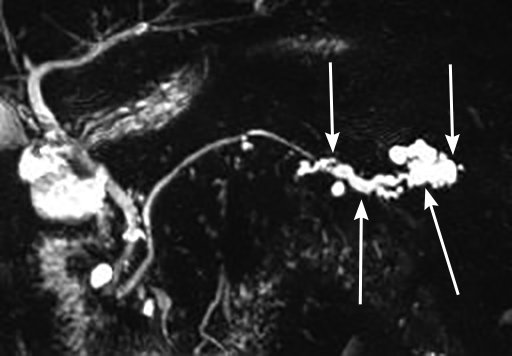

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram of a main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the tail of the pancreas. Cystic dilation of the main pancreatic duct in the tail is seen (arrows).

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram of a main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the tail of the pancreas. Cystic dilation of the main pancreatic duct in the tail is seen (arrows).

Mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN) are mucin-producing cysts seen almost exclusively in women (more than 98%) and found in the pancreas body or tail in 90% of cases. They have a thick fibrous capsule with epithelioid cells similar to ovarian stroma surrounding the tumor. Differentiating mucinous cysts from serous cysts, pseudocysts, and cystic neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas can be challenging, as there is no definitive test with high sensitivity and specificity. Endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration is used for cyst fluid analysis in worrisome lesions; carcinoembryonic antigen levels are frequently elevated in patients with mucinous cysts, whereas serum amylase levels are often elevated in patients with pseudocysts. Cytology of cyst fluid has a low sensitivity (<60%) and is an unreliable predictor of malignant transformation.

Surgical resection of high-risk cysts is currently the only option for treatment. In 2018, the American Gastroenterological Association published guidelines based on expert opinion for the management of asymptomatic cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Worrisome features include symptoms related to the cyst (jaundice, pancreatitis), size of 3 cm or greater, dilated main pancreatic duct (main duct IPMN), and a solid component. MRI is preferred for surveillance. Surveillance can be discontinued if no worrisome features develop over 5 years or if the patient is no longer a surgical candidate.

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are rare, representing 3% of primary pancreatic neoplasms. Ten to twenty-five percent of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are functional and hypersecrete hormones. Tumors may be sporadic or part of an inherited disorder. Initial evaluation includes blood and urine tests for chromogranin A, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, gastrin, glucagon, insulin and proinsulin (if clinically indicated; requires fasting with concurrent glucose), pancreatic polypeptide, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide to determine functional status. Most functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors secrete gastrin (gastrinoma) or insulin (insulinoma). Genetic testing for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 is recommended in all young patients with gastrinomas or insulinomas, and in any patient with a family or personal history of other endocrinopathies or multiple pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Genetic testing for other associated inherited disorders, such as von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, or neurofibromatosis–1, should be considered based on clinical and family history.

Imaging is recommended with multiphasic CT or MRI of the abdomen. Endoscopic ultrasonography (90% sensitive) or octreotide scintigraphy may be needed to detect small lesions. For functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, surgery is recommended if more than 90% of the tumor can be resected. For nonfunctional tumors associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, surgery is usually recommended if the tumors are greater than 2 to 3 cm in size. Medical management of gastrinomas includes oral proton pump inhibitors two or three times daily or somatostatin analogs. High-volume or progressive disease is best managed in conjunction with a gastroenterologist.

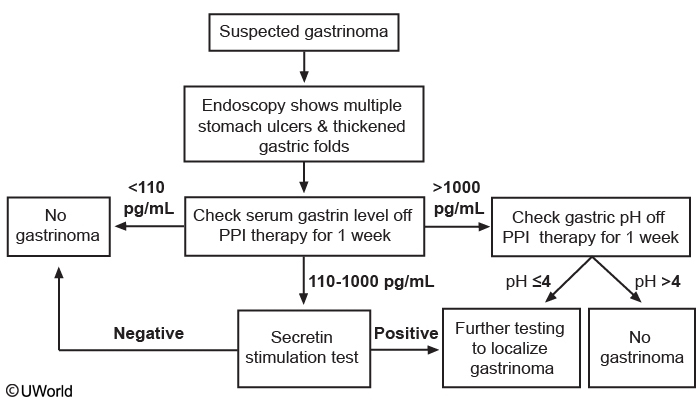

Gastrinoma

This patient’s presentation and endoscopic findings suggest gastrinoma (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), which can be sporadic or found in conjunction with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) in 20% of cases. Gastrinomas usually present in patients age 20-50 with dyspepsia, reflux symptoms, abdominal pain, weight loss, or frank gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy often shows thickened gastric folds, multiple peptic ulcers, refractory ulcers despite proton pump inhibitor use, or ulcers distal to the duodenum in the jejunum. The gastrin level should be checked in suspected gastrinoma; a level < 110 pg/mL rules it out.

A gastrin level > 1000 pg/mL is highly suggestive and requires checking the gastric pH, with pH > 4 ruling out gastrinoma. A pH < 4 suggests gastrinoma and requires further testing (eg, endoscopic ultrasound, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, and CT or MRI) for localization.

A gastrin level of 110-1000 pg/mL requires a follow-up secretin stimulation test. A negative secretin test rules out gastrinoma; a positive test requires further localization testing. Gastrinoma associated with MEN-1 syndrome usually responds to proton pump therapy. However, surgery is usually preferred for sporadic gastrinomas or MEN-1 patients with uncontrolled symptoms on medical therapy.