Disorders of the Liver

- related: GI

- tags: #GI

Approach to the Patient with Abnormal Liver Chemistry Studies

Basic metabolic panels commonly include liver chemistry tests. Liver chemistry tests are often abnormal (10% to 20% of the time); therefore, it is important to take a systematic approach to their evaluation. The patterns of the elevations of liver tests can be used to group causes into categories; however, these patterns are not specific. Elevations of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels represent hepatic parenchymal inflammation. Elevated ALT levels are more specific for hepatic inflammation because AST is also found in other tissues such as heart and muscle.

Elevations in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and bilirubin levels result from inflammation of the biliary tree or bile flow abnormalities. ALP is also produced in bone and placenta and high levels are seen in pregnancy. Elevation of ALP and other liver chemistries typically reflects liver injury. Fractionation of ALP levels can be performed to determine the source of elevation. Bilirubin can be divided into conjugated and unconjugated forms. Elevation of conjugated bilirubin reflects a liver disorder, whereas elevation of unconjugated bilirubin is seen in hematological disease or in benign alterations of bilirubin conjugation, such as Gilbert syndrome.

The prothrombin time and serum albumin levels reflect the synthetic function of the liver. Albumin levels are decreased in the setting of malnourishment, the nephrotic syndrome, acute inflammation, and protein-losing enteropathies. Prothrombin time can be prolonged in vitamin K deficiency, warfarin therapy, coagulopathy of liver disease, inherited or acquired factor deficiency, and the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. In patients with abnormal liver enzyme levels, thrombocytopenia may be a clue to the presence of portal hypertension.

The relative levels and severity of elevations of AST, ALT, and ALP provide clues about the cause of the liver inflammation (Table 26). The duration of abnormal liver tests is also important in evaluating the causes of liver injury. Acute liver inflammation is defined as less than 6 months in duration, whereas chronic hepatitis is defined as elevated liver chemistries of greater than 6 months' duration.

Abdominal imaging can be helpful in the assessment of a patient with abnormal liver tests. Abdominal ultrasonography may show increased echogenicity, consistent with fatty infiltration of the liver, as well as nodularity of the liver seen in the setting of cirrhosis. Cross-sectional imaging may show findings of fatty infiltration of the liver as well as changes of cirrhosis. Noninvasive assessments of hepatic fibrosis are becoming more frequently used. Ultrasound-based transient elastography and magnetic resonance (MR) elastography measure tissue stiffness. Tissue stiffness correlates with stages of hepatic fibrosis, although high stiffness values may also occur with hepatic congestion, infiltrative disorders, and bile duct obstruction.

Viral Hepatitis

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is an RNA virus that causes acute hepatitis mediated by the host immune response. HAV infection is a self-limited illness, but atypical forms exist, including a relapsing, remitting infection with cholestatic features and, rarely, acute liver failure. HAV is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. Risk factors include international travel, contacts with household members with HAV infection, men who have sex with men, homelessness, and exposure to day care or institutionalized settings. The incidence of HAV infection declined dramatically after introduction of universal childhood HAV vaccination, but rates have recently increased among unvaccinated people, especially those reporting homelessness or drug use (see MKSAP 18 Infectious Disease).

Mortality is rare but may be increased in patients with preexisting chronic liver disease. The incubation period for HAV is 15 to 50 days. A prodrome of malaise, nausea, vomiting, fever, and right-upper-quadrant pain is followed by development of jaundice, with physical examination findings of jaundice and hepatomegaly. HAV can be transmitted during the prodrome stage and up to 1 week after development of jaundice. Laboratory studies may show aminotransferase levels greater than 1000 U/L and total bilirubin level of 10 mg/dL (171 µmol/L) or higher, mostly direct (conjugated). A positive test for IgM antibodies to HAV is suggestive of acute illness, although false positives may occur in the setting of other viral infections. The presence of IgG antibodies to HAV indicates previous infection or vaccination and provides immunity from reinfection. Treatment is supportive, and 90% of patients or more recover fully within 3 to 6 months of infection.

Either of the two inactivated cell culture–produced vaccines that have become part of the recommended routine childhood vaccine schedule can be used. In addition to avoiding potentially contaminated food and water, vaccination is also strongly advised for those planning to travel to areas that pose significant risk of infection. Ideally, vaccination should occur at least 2 to 4 weeks before departure. Nevertheless, a single dose of vaccine given any time before travel provides adequate protection in otherwise healthy persons. Depending on the particular vaccine product used, a second dose is administered between 6 to 18 months later.

Passive immunization with intramuscular immune globulin adds no benefit when administered alone or in combination with vaccination for most healthy patients when time before travel is short. However, to optimally guard against infection, immune globulin is recommended with vaccination in persons with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions, immunocompromised states, and older adults if travel is scheduled in less than 2 weeks. Immune globulin alone would also be warranted in persons who are allergic to or decline vaccination and in children younger than 12 months for whom the vaccine is not approved.

For postexposure prophylaxis, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that HAV vaccine be administered to all persons aged 12 months or older. In addition to HAV vaccine, immunoglobulin may be administered to persons aged 40 years or older depending on the provider's risk assessment. Persons who have recently been exposed to HAV and who have not been immunized should receive postexposure prophylaxis as soon as possible, within 2 weeks of exposure.

Hepatitis B

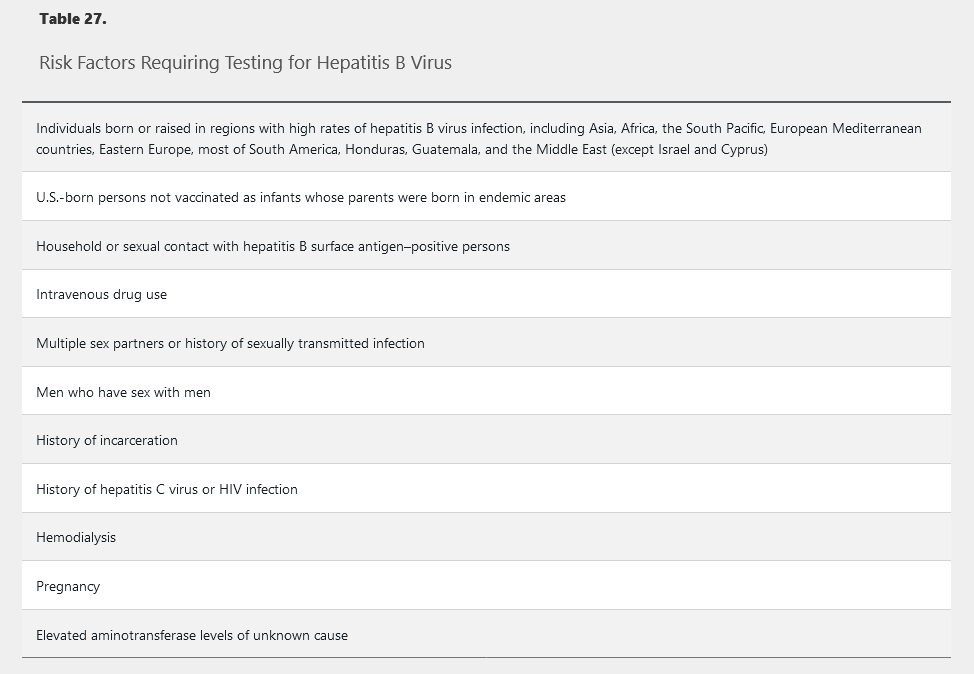

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus affecting 240 million persons worldwide and 2.2 million in the United States. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for HBV vaccination strategies. HBV can be transmitted vertically, through sexual exposure, percutaneously, or by close person-to-person contact. The risk for developing chronic HBV infection differs by age. Newborns acquiring HBV have the highest risk (90%), whereas adults have an approximately 5% risk. Testing for HBV is recommended in individuals with risk factors (Table 27).

HBV infection presents as acute hepatitis in a minority of patients. Approximately 30% of adults may develop jaundice as a result of acute infection with aminotransferase levels as high as 3000 U/L and nonspecific symptoms including malaise, nausea, and right-upper-quadrant pain. Acute liver failure (ALF) develops in approximately 0.5% of patients. Typically, adult patients recover within 1 to 4 months. Chronic HBV infection is diagnosed after 6 months in patients with persistent hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) detected in serum.

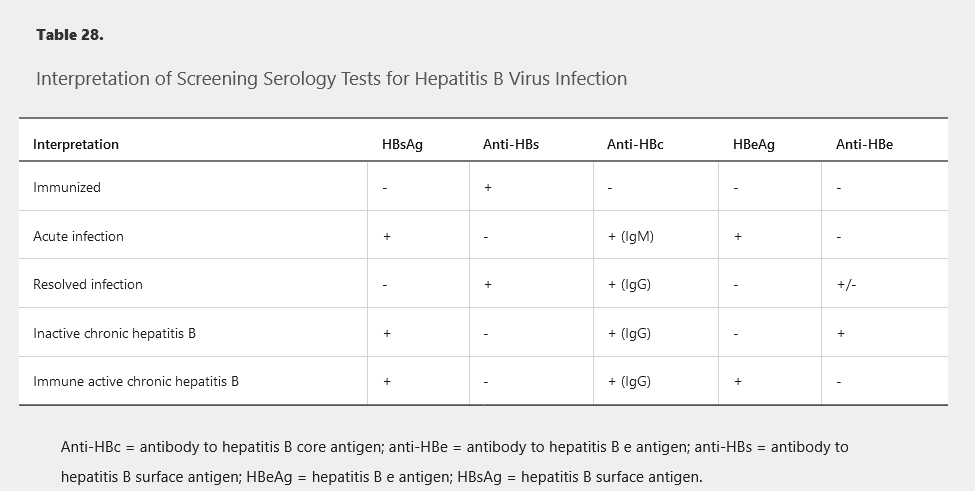

Interpretation of HBV screening serologies is shown in Table 28.

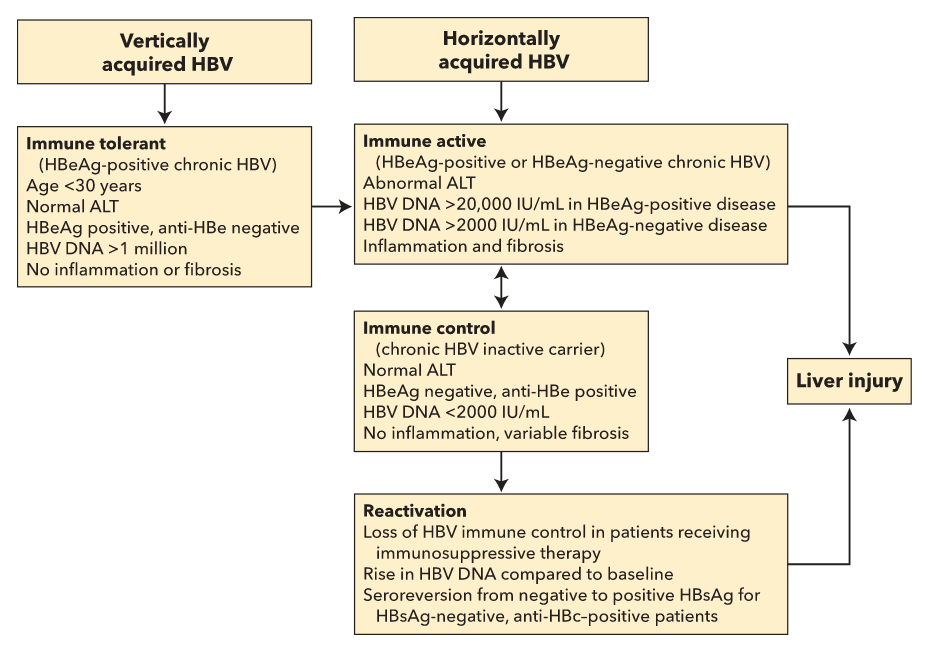

There are four phases of chronic HBV infection: immune tolerant, immune active, immune control (inactive chronic HBV infection), and reactivation (Figure 30).

Phases of chronic hepatitis B infection. It is assumed that patients progress through the phases in sequence, although not all patients develop HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B, and only patients with vertical transmission of hepatitis B have a clinically recognized immune tolerant phase. All phases have positive HBsAg, negative anti-HBs, and positive IgG anti-HBc.

Phases of chronic hepatitis B infection. It is assumed that patients progress through the phases in sequence, although not all patients develop HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B, and only patients with vertical transmission of hepatitis B have a clinically recognized immune tolerant phase. All phases have positive HBsAg, negative anti-HBs, and positive IgG anti-HBc.

Patients who have acquired HBV through vertical transmission remain in the immune-tolerant phase for the first two to three decades. This stage does not require treatment except in specific cases (patients older than 40 years with an HBV DNA level of at least 1 million IU/mL and significant inflammation or fibrosis). Patients from Southeast Asia should undergo hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance with ultrasonography starting at age 40 years for men and at age 50 years for women, and patients from sub-Saharan Africa should begin at age 20 years.

Patients transition to immune-active hepatitis later in life. Hallmarks of the immune-active phase include intermittently or persistently elevated ALT levels, an HBV DNA level of at least 20,000 IU/mL in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive disease (most common), and greater than 2000 IU/mL in HBeAg-negative disease. Moderate to severe inflammation can occur, fibrosis can progress, and treatment is warranted in this phase.

Spontaneous seroconversion to the immune-control (inactive) phase with a loss of HBeAg and development of antibody to hepatitis B e antigen (anti-HBe) occurs at a rate of 10% per year. To be considered inactive, the ALT level must be normal and the HBV DNA level must be 2000 IU/mL or lower when measured every 3 to 4 months for 1 year.

Reactivation of chronic HBV infection results from loss of immune control in patients with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive and antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc)-positive disease or in those with HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc–positive disease. This occurs in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy for another medical condition. Reactivation is characterized by a rise in HBV DNA compared to baseline and seroconversion from HBsAg-negative to HBsAg-positive in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc–positive patients. Reactivation predisposes to a hepatitis flare evidenced by a rise in the ALT more than 3-fold over baseline level and greater than 100 U/L.

HBsAg-positive patients are at high risk for HBV reactivation, and anti-HBV prophylaxis is recommended before the initiation of immunosuppressive or cytotoxic therapy. HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc–positive patients are at lower risk for reactivation and can be managed with either anti-HBV prophylaxis before initiation of immunosuppressive or cytotoxic therapy or monitoring and treatment with anti-HBV therapy at the time of reactivation. Prophylactic oral antiviral therapy should be given to patients who are HBsAg-positive or isolated core antibody–positive and receiving B-cell depleting therapy (for example, rituximab, or ofatumumab), prednisone (≥10 mg/d for at least 4 weeks), or anthracycline derivatives. Patients undergoing therapy with tumor necrosis factor-α or tyrosine kinase inhibitors should be considered for prophylaxis.

Risk factors for the development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic HBV infection are listed in Table 29.

Treatment is advised for patients with acute liver failure, infection in the immune-active phase or reactivation phase, and cirrhosis, and in selected immunosuppressed patients. First-line treatment is entecavir or tenofovir. Lamivudine, adefovir, and telbivudine are less commonly used due to resistance. Pegylated interferon can be used for 48 weeks in patients with high ALT levels, low HBV DNA levels, and without cirrhosis. Candidates for interferon are those who have a desire for finite therapy, are not pregnant, and do not have significant psychiatric disease, cardiac disease, seizure disorder, cytopenia, or autoimmune disease.

Treatment goals for patients in the HBeAg-positive, immune-active phase are HBeAg loss and anti-HBe seroconversion, which should be followed by an additional 12 months of treatment. Goals of treatment in the HBeAg-negative, reactivation phase are HBV DNA suppression and ALT normalization; oral antiviral agents are generally continued indefinitely. Patients with cirrhosis should continue oral antiviral medications indefinitely. HBsAg seroconversion rarely occurs with oral antiviral treatment and, therefore, is not a goal of treatment. Regression of fibrosis and even of cirrhosis can occur with treatment.

Rarely, patients with HBV infection develop membranous nephropathy, membranoproliferative nephropathy, polyarteritis nodosa or cryoglobulinemia, which should prompt treatment with oral antiviral therapy.

The survival rate after liver transplantation for end-stage liver disease from HBV infection is greater than 90% at 1 year. Recurrence of HBV infection in transplant recipients is prevented with HBV immunoglobulin and/or oral antiviral therapy.

The prognosis for untreated individuals with HBV infection worsens with age, particularly with age older than 40 years. Approximately 40% of deaths in HBV-infected persons older than age 40 years are related to hepatocellular carcinoma or decompensated cirrhosis. The following characteristics are associated with an increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HBV infection and are indications for surveillance with ultrasound or cross-sectional imaging every 6 months: (1) cirrhosis; (2) Asian descent plus male sex plus age older than 40 years; (3) Asian descent plus female sex plus age older than 50 years; (4) sub-Saharan African descent plus age older than 20 years; (5) persistent inflammatory activity (defined as an elevated ALT level and HBV DNA levels greater than 10,000 IU/mL for at least a few years); and (6) a family history of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatitis C

Worldwide, 130 to 150 million individuals are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), with 2.7 to 3.9 million individuals with HCV infection in the United States. HCV is most commonly transmitted through intravenous or intranasal drug use, blood transfusions before 1992, or sexual intercourse. The efficiency of the virus' spread through vaginal intercourse is low. All patients aged 18 to 79 years should be screened for HCV. Although guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force suggest not screening patients older than 79 years in the absence of specific risk factors, the CDC does not specify an upper age limit. Patients with risk factors should be tested (Table 30).

Acute HCV infection is asymptomatic in most patients. Jaundice, nausea, right-upper-quadrant pain, dark urine, and acholic stools can occur in the symptomatic cases. Evaluation of suspected acute infection includes HCV antibody and RNA tests. The HCV RNA test becomes positive first, and the HCV antibody test becomes positive within 1 to 3 months. HCV antibody seroconversion within 12 weeks in the presence of an initial positive HCV RNA test confirms an acute HCV infection. Infection that clears spontaneously, usually within 6 months, is more common in patients with symptoms, high ALT levels, female sex, younger age, and the IL-28 CC genotype. Monitoring HCV RNA quantification for clearance for 6 months is recommended in patients with acute infection.

HCV results in chronic infection in 60% to 80% of patients, with up to 30% progressing to cirrhosis over two to three decades. Patients with cirrhosis have a 2% to 4% risk per year for developing hepatocellular carcinoma.

The first step in the diagnosis of chronic HCV infection is HCV antibody testing, and if positive, a HCV RNA quantification. Patients with positive HCV antibody and RNA tests have active infection, and a genotype test should be performed. Asymptomatic patients with a positive HCV antibody and a negative HCV RNA test, and without recent exposure to HCV, do not have active infection and generally do not require further testing.

All patients infected with HCV should be tested for HBV and HIV because of the potential shared routes of transmission. HBV testing should include HBsAg to assess for active infection (followed by HBV DNA if positive) and antibodies to hepatitis B antigens (anti-HBs and anti-HBc) to assess for past infection. Susceptible patients should receive HBV vaccination. HBV reactivation can be seen during treatment of HCV infection with direct-acting antiviral therapy. Patients who test positive for HBsAg with detectable HBV DNA and who do not meet standard HBV treatment criteria should undergo HBV DNA monitoring approximately every 4 weeks until 12 weeks after completion of treatment for HCV infection, or they can be treated with oral HBV therapy prophylactically.

Patients with chronic HCV infection require a fibrosis assessment with a transient or MRI elastography or liver biopsy, unless they have a documented short duration of disease, decompensated cirrhosis, or a radiologic diagnosis of cirrhosis.

All patients infected with HCV should be considered for treatment unless there are significant life-limiting comorbidities or major barriers to adherence to treatment.

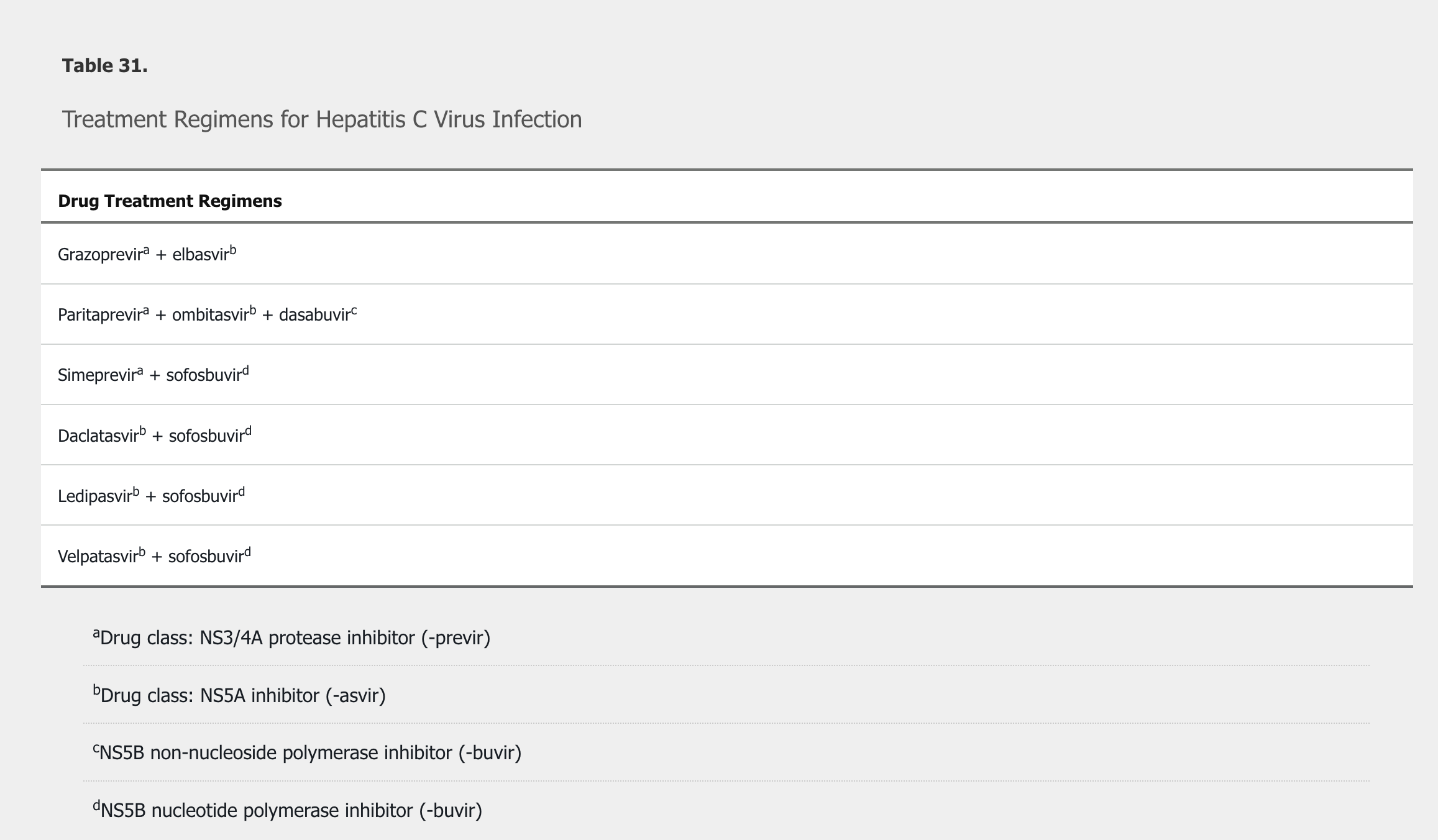

Treatment regimens include a combination of direct-acting antivirals, using different mechanisms to prevent viral reproduction (Table 31). Regimens are chosen based on genotype, previous treatment experience and response, and fibrosis status. Patients whose infection does not respond to newer regimens are generally managed by a hepatologist or infectious disease specialist because resistance-associated substitution–guided retreatment may be necessary. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis should see a hepatologist before treatment and be considered for liver transplantation. Post–liver transplantation recurrence of HCV infection is universal in treatment-naïve patients. Success rates of HCV treatment after liver transplantation are excellent.

Cure is defined by the absence of HCV RNA in blood 12 weeks after completion of treatment. HCV antibodies remain positive indefinitely and should not be rechecked. Patients can become reinfected after new exposures, and HCV RNA testing is appropriate to identify new infection. Cure rates exceed 90% in the majority of patients. Virologic cure reduces the risk for progression to cirrhosis, complications of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related mortality. Patients with stage F3 fibrosis or cirrhosis require ongoing surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma even after virologic cure. Patients with cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma are more likely to experience remission when HCV is eradicated.

"A combination of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir is the most appropriate treatment for this patient. The patient has Meltzer triad—consisting of asthenia, arthralgia, and palpable purpura—which is the classic presentation of type II mixed cryoglobulinemia, a vasculitis that most often arises in the context of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Meltzer triad is seen in less than 30% of patients, but nearly all patients with type II cryoglobulinemia develop cutaneous findings, as seen in this patient. Other findings may include peripheral neuropathy; membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; and pulmonary, central nervous system, or gastrointestinal vasculitis. Urinalysis may show dysmorphic erythrocytes and proteinuria, which are features of glomerulonephritis, but this patient shows no evidence of kidney involvement or other end-organ damage. The best initial treatment for a mild presentation of mixed cryoglobulinemia arising from chronic HCV infection is to treat and eradicate HCV with sofosbuvir-ledipasvir. Other direct-acting antiviral agents that could be used interchangeably to treat genotype 1 HCV include grazoprevir-elbasvir; paritaprevir-ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir; glecaprevir-pibrentasvir; sofosbuvir-daclatasvir; and sofosbuvir-velpatasvir. It is expected that other combinations of direct-acting antivirals will be developed. Treatment of HCV infection with direct-acting antiviral combinations results in a sustained virologic response (cure) in more than 90% of patients, even in those who were previously and unsuccessfully treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. In approximately 90% of cases, eradication of HCV leads to resolution of the mixed cryoglobulinemia.

Most of the data pertaining to the treatment of HCV infection in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia involve treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. However, pegylated interferon and ribavirin are no longer recommended for treatment of HCV infection due to adverse effects and lower efficacy compared to interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral therapy."

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a defective RNA virus that requires HBV for human infection. HDV is endemic in the Mediterranean basin and Pacific islands and uncommon in Western countries. The diagnosis of HDV infection is made through detection of HDV IgG. The clinical course can range from inactive disease to progressive liver disease (in the case of simultaneous HBV-HDV coinfection) to fulminant hepatitis in HDV superinfection. Patients infected with HDV with evidence of progressive liver disease should receive treatment with pegylated interferon for 12 months; cure rates are 25% to 45%.

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an RNA virus with worldwide distribution. There are four different genotypes: genotypes 1 and 2 are more common in developing countries and are transmitted by the fecal-oral route through contaminated water; genotypes 3 and 4 are more common in developed countries where transmission occurs through contaminated food, mostly pork or deer meat. In developing countries, HEV infection generally occurs in young adults and can occur in large epidemics. In developed countries, HEV generally affects males older than age 40 years. The incubation period is 2 to 5 weeks. Approximately 50% of cases are asymptomatic. Symptoms of HEV infection are jaundice, malaise, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and right-upper-quadrant pain. Aminotransferase levels are usually elevated to 1000 to 3000 U/L. Diagnosis relies on detection of HEV IgM or RNA. Treatment is supportive, and recovery is expected within 4 to 6 weeks. HEV infection should be considered in patients with an unknown cause of acute hepatitis and in immunocompromised patients with chronic hepatitis. Solid-organ transplant recipients with chronic hepatitis E have response rates of 70% with ribavirin treatment.

Other Viruses

Other viruses can causes hepatitis, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus, and parvovirus. Approximately 90% of EBV-infected individuals have mild hepatitis, occasionally developing jaundice and elevated ALP levels. Diagnostic testing includes heterophile antibody testing or checking EBV serologies, which may demonstrate a positive viral-capsid antigen IgM. Treatment is supportive.

CMV can cause a syndrome that mimics EBV-related mononucleosis. CMV infection can cause mild aminotransferase elevations. Diagnosis is made with CMV serologies in the immunocompetent host. Treatment is supportive, and spontaneous recovery is the norm. CMV infection in solid-organ transplant recipients can cause CMV syndrome, marked by fever and myelosuppression, or tissue-invasive CMV infection involving the gastrointestinal tract, liver, lungs, and retina. Treatment with intravenous ganciclovir is required in immunocompromised hosts. Without treatment, CMV infection carries a high mortality rate in immunocompromised hosts.

HSV-caused hepatitis in women in the third trimester of pregnancy manifests with fever, altered mental status, right-upper-quadrant pain, hepatomegaly, and a presentation similar to sepsis. Aminotransferase levels are commonly elevated to 5000 U/L or higher with a disproportionately low bilirubin level, accompanied by coagulopathy. Diagnosis can be confirmed with polymerase chain reaction testing for HSV (when available) or a liver biopsy showing intranuclear inclusions, multinucleated giant cells, and coagulative necrosis with minimal inflammation. Intravenous acyclovir is the treatment of choice. The case fatality rate is approximately 80% in untreated patients.

In adults, primary varicella zoster virus is a very rare cause of acute hepatitis. Primary infection in organ transplant recipients can cause acute liver failure. Diagnosis in immunocompromised patients requires a biopsy of the skin or of the affected organ. Treatment is intravenous acyclovir.

Parvovirus B19 can result in transient elevation of aminotransferase levels but has also been associated with fulminant hepatic failure in very rare instances.

Other viruses associated with elevated liver chemistries include human herpes virus 6, 7, and 8, as well as adenoviruses.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic inflammatory hepatitis that is four times more common in women than in men and can be associated with other autoimmune diseases (most commonly autoimmune thyroiditis, synovitis, or ulcerative colitis). It can affect individuals at any age but most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. The presentation of autoimmune hepatitis can vary from asymptomatic elevation of transaminase levels to extrahepatic symptoms such as myalgia and malaise to acute liver failure. Diagnosis is made based on laboratory results (including positive antinuclear and smooth-muscle antibodies and elevated IgG levels), exclusion of other diagnoses (such as Wilson disease, viral hepatitis, and drug-induced liver injury), and histologic findings on liver biopsy.

Treatment includes prednisone and azathioprine for most patients. For uncomplicated autoimmune hepatitis without cirrhosis, budesonide can be considered in place of prednisone, but its role is not established. Prednisone monotherapy is less preferable due to adverse effects. Azathioprine requires monitoring for cytopenia. Typically, biochemical response occurs within 3 to 8 months for the 85% of patients whose disease responds to standard treatment. Histologic response can lag by many months. Duration of treatment should be 2 to 3 years before consideration of withdrawal. A liver biopsy is recommended to determine histologic response before consideration of drug withdrawal. High rates of relapse after discontinuation of treatment underscore the need for serial monitoring of liver tests. Patients with a severe acute form of autoimmune hepatitis presenting with jaundice should be managed by a hepatologist, and patients with features of acute liver failure require urgent transfer to a transplant center.

Alcohol-Induced Liver Disease

Alcohol-induced liver disease is the second most common reason for liver transplantation in the United States. Alcohol injury to the liver may take the form of steatosis, steatohepatitis, or severe steatohepatitis, also known as alcoholic hepatitis. Approximately 25% of heavy drinkers develop cirrhosis. History of alcohol use is the most important component in making the diagnosis, although not all patients are forthcoming about alcohol use. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for more information about screening for alcohol abuse. Most patients with alcoholic liver disease have consumed more than 100 g of alcohol daily for 20 years. The Alcoholic Liver Disease/Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Index score (www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/model-end-stage-liver-disease/alcoholic-liver-disease-nonalcoholic-fatty-liver-disease-index) can be helpful in distinguishing alcoholic liver disease from nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. It includes the following variables: AST, ALT, mean corpuscular volume, age, height, weight, and sex. Physical examination may show evidence of hepatomegaly in patients with steatosis or steatohepatitis. In patients with alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis, findings of advanced liver disease may be present, including muscle wasting, scleral icterus, jaundice, spider angiomata, gynecomastia, left hepatic lobe hypertrophy, testicular atrophy, or palmar erythema. Laboratory evaluation of alcohol-related liver disease may show an elevated mean corpuscular volume, AST:ALT ratio greater than 2, elevated γ-glutamyl transferase level, and in advanced cases, elevated INR and thrombocytopenia.

Manifestations of alcoholic hepatitis include fever, jaundice, tender hepatomegaly, and leukocytosis. Ultrasound or cross-sectional imaging may reveal evidence of steatosis, cirrhosis, and findings consistent with portal hypertension. The diagnosis is most often made clinically, with liver biopsy reserved for cases with diagnostic uncertainty. Severity of alcoholic hepatitis is determined by the Maddrey discriminant function (MDF) score, which is calculated as follows:

MDF score = 4.6 (prothrombin time [s] – control prothrombin time [s]) + total bilirubin (mg/dL)

In severe cases, as defined by an MDF score of 32 or greater or the presence of hepatic encephalopathy, treatment with prednisolone is recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guideline. Use of the MDF score, however, can be limited by variability in prothrombin time measurement. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/allocation-calculators/meld-calculator/) can also be used to assess severity, with a MELD score greater than 20 suggesting moderate to severe disease. Contraindications to prednisolone include active infection, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, acute kidney injury, concomitant liver disease (especially HCV and HBV infections), and multiorgan failure.

The STOPAH trial showed a trend toward improvement in 28-day mortality with the use of prednisolone, but results were not statistically significant. However, a meta-analysis of randomized studies (including the STOPAH study) showed that glucocorticoids were effective in reducing short-term mortality by 46%. Response to glucocorticoids can be assessed on day 7 with the Lille score (https://www.mdcalc.com/lille-model-alcoholic-hepatitis). Because of risk for infection, prednisolone should be discontinued in patients with no response (Lille score ≥0.45). Lille scores less than 0.45 support prednisolone continuation for 28 days.

Nonsevere alcoholic hepatitis (MDF score <32) requires supportive measures and should not be treated with prednisolone. All patients require assessment for nutritional deficiencies, thiamine replacement, and alcohol treatment with a goal of abstinence. Pentoxifylline is not effective for alcoholic hepatitis, and its use is not recommended.

Alcoholic cirrhosis can be diagnosed on clinical and radiologic grounds in patients with obvious evidence of portal hypertension and a history of consistent alcohol intake. Occasionally a liver biopsy is necessary in cases with diagnostic ambiguity. In patients who drink alcohol, inflammation of the liver increases stiffness, making transient and MR elastography inaccurate. Nutritional assessments and alcohol treatment are required. Alcohol abstinence can result in significant stabilization of liver function and reversal of portal hypertension. Liver transplantation is reserved for appropriate candidates who are at low risk for alcohol relapse. Risk for relapse is best determined by specialists in addiction medicine rather than using criteria based on a specific duration of abstinence.

Drug-Induced Liver Injury

Drug-induced liver injury encompasses a spectrum of liver injury and can be induced by many medications. Prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal medications have been implicated. Acetaminophen is the most recognized medication to have intrinsic hepatotoxicity, and its pattern of liver injury is easily recognizable. People who chronically drink alcohol can develop acetaminophen hepatotoxicity even when taking therapeutic doses of acetaminophen. The early recognition of acetaminophen-induced liver injury is critical so that N-acetylcysteine can be administered promptly to prevent liver failure.

Antibiotic (particularly amoxicillin-clavulanate) and antiepileptic medications (phenytoin and valproate) are among the most common medications associated with drug-induced liver injury, representing 60% of cases. The most common antimicrobials that cause acute liver failure in the United States are antituberculosis drugs, sulfa-containing antimicrobial agents, and antifungal agents. The pattern of liver test abnormalities and histological injury can be unpredictable. Some medications, such as amoxicillin-clavulanate, can cause a cholestatic hepatitis, whereas others, such as erythromycin, can cause differing patterns of liver pathology. Patients should be asked about exposure within the past 6 months to medications, both prescription and nonprescription as well as herbal and dietary supplements. Withdrawal of the potentially offending drug with resolution of liver injury supports the diagnosis. Re-exposure to the drug to demonstrate recurrence is not advisable, due to the risk of severe hepatitis upon rechallenge.

Jaundice that occurs in the setting of cholestatic drug reactions can take months to resolve. An elevated bilirubin level in the setting of increased hepatic transaminases greater than three times the upper limit of normal is associated with mortality rates as high as 14%. Until resolution occurs, there is potential for progression to liver failure and a need for liver transplantation.

Acute Liver Failure

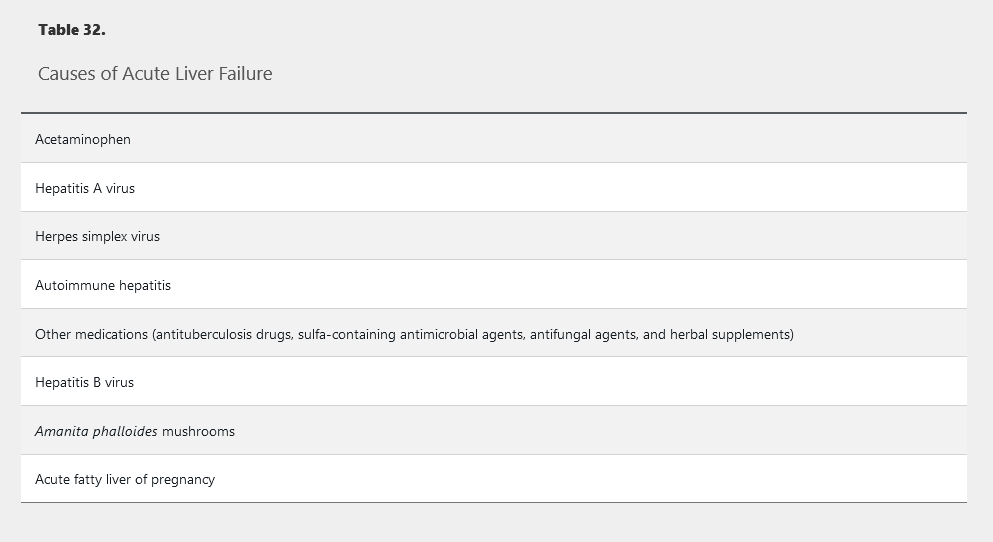

Acute liver failure is defined as the onset of hepatic encephalopathy and a prolonged prothrombin time within 26 weeks of occurrence of jaundice or other symptoms of liver inflammation in the absence of chronic liver disease. The most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States is acetaminophen overdose. Other widely recognized causes are presented in Table 32. The diagnosis requires immediate referral to a liver transplant center.

Patients with acute liver failure require careful monitoring of mental status because progressive hepatic encephalopathy can result in cerebral edema (see Hepatic Encephalopathy). Kidney injury is common, and continuous renal replacement therapy is better tolerated than intermittent hemodialysis. Patients with acute liver failure are at risk for hypoglycemia and infection.

Specific treatment is based on the cause: N-acetylcysteine is used for acetaminophen intoxication; antiviral medications for HBV infection and herpes simplex hepatitis; penicillin G for Amanita mushroom poisoning; and delivery of the fetus for acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Prompt treatment is crucial. For example, mortality rates for acetaminophen intoxication are lowest when N-acetylcysteine is administered within 12 hours of ingestion.

Metabolic Liver Diseases

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of liver disease in the world. Some 30% of the U.S. population may be affected by this condition. Most patients with NAFLD do not have liver inflammation. In these patients, the presence of fat in the liver without inflammation or fibrosis is considered a benign condition. Patients who have fatty liver with inflammation (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH]) have progressive disease that can lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis. NAFLD usually develops due to the metabolic syndrome, leading to triglyceride accumulation within the liver. Consequently, the American Diabetes Association recommends that patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes and elevated ALT or fatty liver on ultrasound should be evaluated for NASH and liver fibrosis. The mechanisms by which patients with NAFLD develop NASH are not fully understood. Metabolic, genetic, and environmental factors likely play a role. Patients with NAFLD are often diagnosed by abdominal imaging. Ultrasound, CT, and MRI can detect the presence of hepatic fat. Symptoms of NAFLD are nonspecific and include fatigue and vague right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain. NASH is characterized by inflammation, risk for progressive fibrosis, and development of cirrhosis. NASH may affect 5% of the U.S. population. Mildly elevated hepatic transaminases are common in NASH. Unrecognized NASH is likely a major cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis.

There are no tests that can diagnose NASH as a cause of chronically elevated liver chemistries. Patients with elevated liver chemistries, a negative serological evaluation for alternative causes, clinical features of the metabolic syndrome, and characteristic abdominal imaging are presumed to have NASH. Low titers of autoantibodies are observed in 20% of patients with NAFLD. The NAFLD fibrosis score (www.nafldscore.com) uses clinical data to identify patients at risk for severe disease. Transient elastography can be used to determine whether patients with NASH have developed significant hepatic fibrosis. Liver biopsy is indicated when the diagnosis is in doubt, or if the presence of hepatic fibrosis cannot otherwise be determined.

The management of NAFLD is focused on weight loss through diet and lifestyle modification. No specific diet for NAFLD is recommended, although carbohydrate-restricted diets may result in greater reduction in liver fat than other diets. Bariatric surgery and concomitant weight loss results in improvement of inflammation and fibrosis associated with NAFLD. No drugs have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of NAFLD. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in patients with NASH, and therapy with statins should be considered.

α1-Antitrypsin Deficiency

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency is a codominant genetic disorder that results in accumulation of a variant protein in the liver. In codominant inheritance, two different versions (alleles) of a gene are expressed rather than only the dominant allele. In situations of codominance, each allele codes for a slightly different protein and both proteins influence the expression of the genetic trait. Homozygosity for this condition may result in liver injury and eventual cirrhosis. The hepatic accumulation of α1-antitrypsin results in decreased circulating α1-antitrypsin, leading to lung disease. Supplemental α1-antitrypsin prevents progressive lung injury but does not affect the progression of cirrhosis. Patients with heterozygosity for α1-antitrypsin deficiency are at increased risk for liver injury in the setting of other liver diseases, including viral hepatitis or fatty liver disease. Liver transplantation is required to treat liver failure resulting from α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Hereditary Hemochromatosis

Hereditary hemochromatosis is a condition characterized by excessive accumulation of iron in the liver due to a mutation in the genes that control the synthesis of hepcidin. Several genetic conditions can cause clinically significant iron overload; hereditary hemochromatosis typically results from homozygosity of the C282Y polymorphism of the HFE gene. Cirrhosis can develop in untreated patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and is associated with an increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Elevated transferrin saturation and elevated serum ferritin levels can suggest a diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis; transferrin saturation is recommended as the initial diagnostic test. Elevations in either test can be seen in other liver diseases, so confirmation of the diagnosis requires genetic testing.

Removal of excessive iron, usually by phlebotomy, effectively prevents the development of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis may be clinically apparent. If it is not apparent based on imaging or physical examination findings, it should be suspected in all patients with hereditary hemochromatosis who have a serum ferritin level greater than 1000 ng/mL (1000 µg/L). Confirmation of cirrhosis is important because surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is recommended in patients with advanced (stage 4) fibrosis. Patients with cirrhosis should undergo iron-lowering therapy to stabilize liver disease and to prevent other organ manifestations of iron overload. Liver failure resulting from hereditary hemochromatosis is treated by liver transplantation.

First-degree relatives of patients with hereditary hemochromatosis should be screened with iron studies, including transferrin saturation and serum ferritin level, with HFE genotype testing if results of iron studies are abnormal. Children of affected patients can be reassured that they do not have hemochromatosis if the other parent is tested for the HFE gene mutation and has a normal genotype, as this would mean that the children are obligate heterozygotes.

Hemochromatosis is discussed further in MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology.

Wilson Disease

Wilson disease is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that causes accumulation of copper in the liver. The accumulation of copper can result in sudden liver failure and the need for emergent liver transplantation, especially in younger patients. Unexplained liver disease or liver failure in any patient younger than age 40 years should prompt an investigation for Wilson disease, although older patients with Wilson disease have also been described.

Decompensated Wilson disease presents with Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia due to the sudden release of copper from hepatocytes. Laboratory findings include high levels of urinary copper and low levels of ceruloplasmin and ALP. Neurological changes can be seen in patients with Wilson disease (tremor, early-onset Parkinson disease, dystonia). Kayser-Fleischer rings can be seen on slit-lamp examination of patients with Wilson disease and neurologic findings. Histological changes on liver biopsy can be nonspecific, although levels of hepatic copper are typically high. Genetic testing for mutations in the ATP7B gene confirms Wilson disease.

Treatment is lifelong and involves administration of copper chelators. Trientine is preferred over penicillamine due to a lower rate of adverse effects. Zinc supplements can be administered to decrease the intestinal absorption of copper.

[!Note] Young patient presenting with new jaundice, hemolytic anemia, high bili

Cholestatic Liver Disease

Determining Prognosis

The Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score (Table 33) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score are prognostic in patients with cirrhosis. The 1-year survival rates for patients with CTP class A, B, and C cirrhosis are 100%, 80%, and 45%, respectively.

The MELD formula includes bilirubin level, INR, and creatinine level, and is accurate in predicting 3-month mortality. Another version of the MELD score, the MELD-Na (https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/allocation-calculators/meld-calculator/), adds sodium to the formula. The MELD score has been the basis for liver transplant allocation since 2002. In 2016, the allocation system was changed to include the MELD-Na score, which was found to be a better predictive model for 3-month mortality.

The MELD score can estimate postoperative mortality in patients with cirrhosis (www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/model-end-stage-liver-disease/post-operative-mortality-risk-patients-cirrhosis).

Complications of Advanced Liver Disease

Patients with chronic liver disease from any cause are at risk for the development of cirrhosis. Uncomplicated cirrhosis is referred to as “compensated cirrhosis” and may be asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific symptoms. Decompensated cirrhosis includes patients with complications such as ascites, jaundice, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatorenal syndrome, variceal hemorrhage, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Portal Hypertension

Portal venous hypertension develops in the setting of advanced cirrhosis due to obstruction of blood flow caused by intrahepatic fibrosis, the development of regenerating liver nodules, and increased intrahepatic vascular resistance. Prehepatic causes, including portal vein thrombosis, and posthepatic causes, such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, can also result in portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis. Hypersplenism, often also associated with thrombocytopenia, further increases flow within the portal vein, exacerbating portal hypertension. Complications of portal hypertension include gastroesophageal varices, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy due to poor hepatic clearance of absorbed nitrogenous compounds from the intestines. These complications of portal hypertension herald a high rate of further complications and mortality, leading to consideration for liver transplantation.

Esophageal Varices

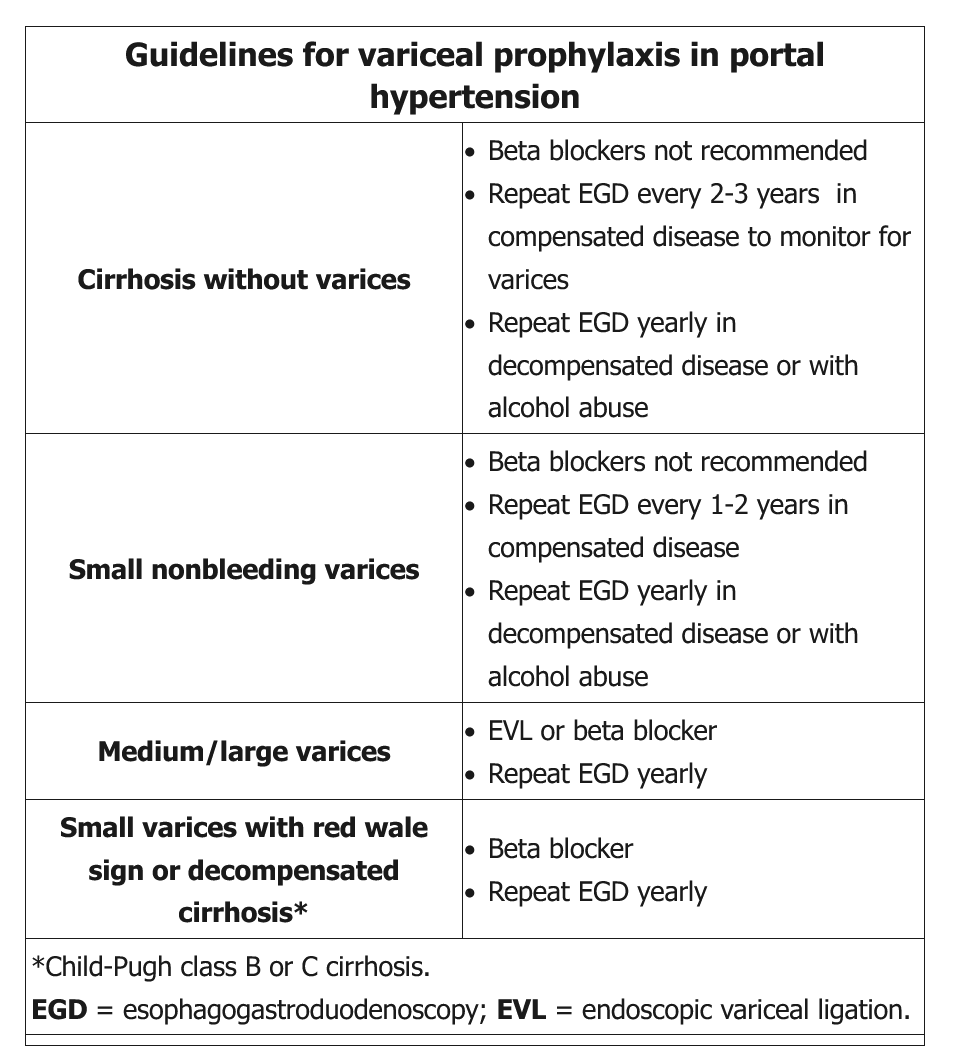

Esophageal varices are enlarged vessels within the lumen of the lower esophagus that provide extrahepatic pathways of blood flow from the portal circulation to the systemic circulation. Over time, esophageal varices enlarge and may spontaneously rupture, leading to bleeding and possible death. The mortality rate for acute variceal hemorrhage has been significantly reduced with treatment. Upper endoscopy should be performed on all patients with cirrhosis to assess for the presence of varices. Management of varices in patients with cirrhosis depends on size of the varix and whether the cirrhosis is compensated (Table 34).

See Gastrointestinal Bleeding for discussion of management and secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.

Gastric Varices and Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Gastric varices are seen in as many as 20% of patients with cirrhosis and are responsible for 10% to 30% of variceal hemorrhage. Varices that extend from the esophagus into the cardia of the stomach are treated with band ligation, like esophageal varices. Varices of the gastric fundus, or isolated varices in other parts of the stomach, are not treated with band ligation. Bleeding varices in these areas should be treated with hemodynamic resuscitation, antibiotic therapy, and octreotide. Cyanoacrylate glue injection can be injected into bleeding gastric varices but is not FDA-approved for this indication. A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) should be considered for bleeding from gastric varices. Splenic vein thrombosis can cause isolated gastric varices and is treated with splenectomy.

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is characterized by brain dysfunction ranging from minimal abnormalities to frank coma. It occurs due to insufficient hepatic function and porto-systemic shunting of blood caused by portal hypertension or vascular shunting. The development of hepatic encephalopathy can be spontaneous or precipitated by other conditions such as infection, sedating medications, volume depletion, or gastrointestinal bleeding, and heralds worsening of liver function.

Minimal manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy can be detected on neuropsychiatric testing, although overt changes of hepatic encephalopathy, ranging from personality changes to frank coma, are common in the setting of advanced cirrhosis (Table 35). Asterixis, a flapping hand tremor, is typically present in middle stages of hepatic encephalopathy. Asterixis is typically absent in subclinical stages of hepatic encephalopathy and is lost as patients progress to later stages of hepatic encephalopathy, including coma.

Patients with hepatic encephalopathy should be monitored in an ICU. Diminishing consciousness should prompt consideration of intubation because airway-protective reflexes can be lost in the advanced stage of hepatic encephalopathy. Measures to reduce intracranial hypertension include elevation of the head of the bed and increasing serum osmolality with mannitol infusions.

The treatment of hepatic encephalopathy is multifaceted. Precipitating causes, such as infection or gastrointestinal bleeding, should be promptly treated. The nonabsorbed disaccharide lactulose is typically administered to decrease absorption of nitrogenous substances. If a suboptimal response is seen with lactulose therapy, rifaximin can be administered to alter bacterial flora in the intestinal lumen. While rifaximin is better tolerated than lactulose, it is more expensive. Initial treatment with lactulose is preferred.

Ascites

Ascites occurs in 50% of patients within 10 years of diagnosis of cirrhosis and is the most common complication of cirrhosis. The finding of a fluid wave on physical examination can detect ascites; other findings are less reliable. Ultrasound is useful for identifying the presence of ascites. When ascites is first detected, diagnostic paracentesis should be performed. The serum-ascites albumin gradient is measured by subtracting the level of albumin in the ascitic fluid from a concurrent serum albumin measurement:

serum-ascites albumin gradient = serum albumin – ascites albumin

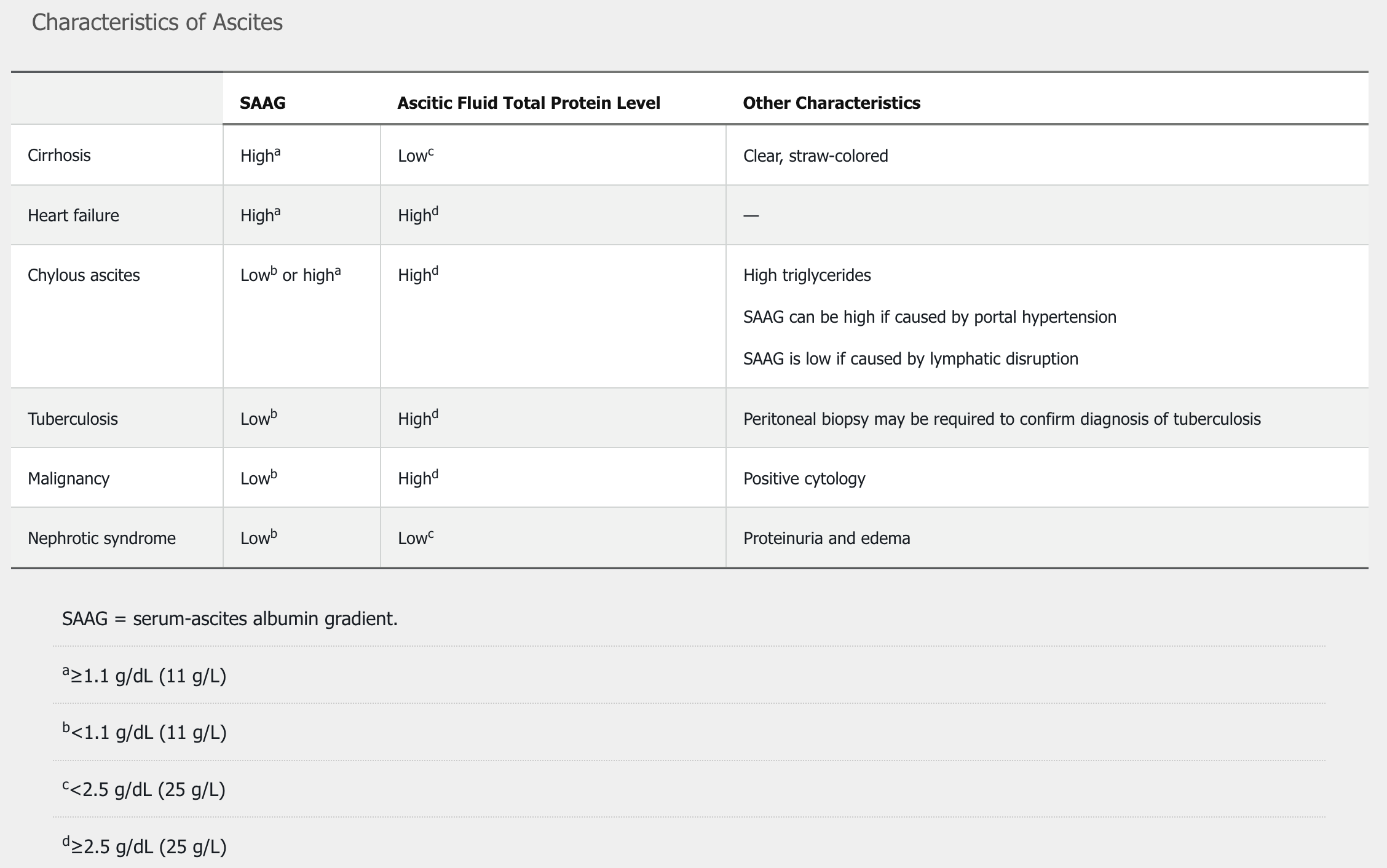

Total protein levels in ascitic fluid also assist in determining the cause of the ascites. The differential diagnosis of ascites is presented in Table 36.

Cirrhosis is the cause in 85% of patients with ascites. The management of ascites involves a sodium-restricted diet (<2 g/d) and diuretic therapy, typically with spironolactone and furosemide. Kidney function and electrolyte levels are typically checked 7 to 10 days after changes to diuretic regimens.

Serial paracenteses can be performed if ascites does not resolve with sodium restriction and diuretic therapy. If more than 5 L of ascitic fluid is removed at one time, supplemental 25% albumin, at a dose of 7 to 9 g/L of ascitic fluid removed, should be administered to prevent circulatory dysfunction after paracentesis.

Patients with ascites should discontinue ACE inhibitors and NSAIDs. TIPS or intermittent paracentesis can be considered in patients with refractory ascites and a low MELD score. Indwelling drains in ascites due to portal hypertension are associated with high rates of complications and are not recommended.

Blood pressure falls with worsening cirrhosis, resulting in reduced renal blood flow and glomerular filtration. A compensatory upregulation of the renin-angiotensin system results in increased levels of vasoconstrictors, including vasopressin, angiotensin, and aldosterone, which support systemic blood pressure and kidney function. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers impair the compensatory response to cirrhosis-related hypotension and thereby impair the ability to excrete excess sodium and water and may also affect survival. Medications that decrease kidney perfusion, including NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors such as lisinopril, and angiotensin receptor blockers, should be discontinued because their use often worsens ascites due to portal hypertension.

Hepatorenal Syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) occurs in the setting of portal hypertension and results from a reduction in renal blood flow during simultaneous dilatation of the splanchnic vasculature. Most patients who develop HRS have cirrhosis, although alcoholic hepatitis and acute liver failure are also associated with this syndrome. Type 1 HRS is characterized by a rise in serum creatinine of at least 0.3 mg/dL (26.5 µmol/L) and/or ≥50% from baseline within 48 hours, bland urinalysis, normal kidney ultrasound, and exclusion of other causes of acute kidney injury. Often patients also have low fractional excretion of sodium and oliguria. Type 2 HRS is characterized by a more gradual decline in kidney function associated with refractory ascites.

Serum creatinine level is one of the most important predictors of death in patients with cirrhosis, and a rapid rise should prompt evaluation for infections and causes of hypovolemia.

Treatment of HRS involves withdrawal of diuretics, volume expansion, with intravenous albumin, and vasoconstrictors. Treatment may also include intravenous albumin with either terlipressin (if available) or midodrine and octreotide to raise mean arterial pressure and improve kidney perfusion. Hemodialysis while awaiting liver transplantation may be required for patients whose kidney function does not improve with therapy.

Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

Hepatopulmonary syndrome is characterized by dilation of intrapulmonary vessels in patients with portal hypertension, resulting in right-to-left shunting of blood and hypoxemia. A high alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient results from functional shunting. Dilation of pulmonary vasculature occurs at the base of the lungs, so hypoxemia is most noted when patients are upright or sitting, when shunting is maximal. Features of hepatopulmonary syndrome include orthodeoxia (worsening oxygen saturation while upright) and platypnea (worsening sense of dyspnea when upright). The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with portal hypertension who have symptoms of dyspnea and evidence of hypoxia. Pulse oximetry is often used to screen for changes in the arterial oxygen saturation level with changes of position. The diagnosis is made by demonstrating an arterial oxygen tension less than 80 mm Hg (10.7 kPa) breathing ambient air, or an alveolar-arterial gradient of 15 mm Hg (2 kPa) or greater, along with evidence of intrapulmonary shunting on echocardiography with agitated saline or macroaggregated albumin study. The detection of intrapulmonary shunting of blood is best confirmed by echocardiography with agitated saline (also known as a bubble study), during which bubbles are identified in the left side of the heart after 5 beats, demonstrating that the shunting of blood is not intracardiac. Hepatopulmonary syndrome is initially treated with supplemental oxygen, but it is uniformly fatal without liver transplantation.

Portopulmonary Hypertension

Patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension who present with dyspnea on exertion should be suspected of having portopulmonary hypertension. While less common than hepatopulmonary syndrome, portopulmonary hypertension is a complication of advanced cirrhosis with a high mortality rate. Echocardiography demonstrates right ventricular systolic pressures greater than 50 mm Hg, which should prompt right-heart catheterization to confirm the diagnosis. Although portopulmonary hypertension was formerly considered a contraindication to liver transplantation, patients with preserved right ventricular function who can attain a mean pulmonary artery pressure of less than 35 mm Hg with the use of vasodilator therapies can benefit from liver transplantation. Prostacyclin analogues, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, and endothelin receptor antagonists have been used to successfully treat portopulmonary hypertension.

Health Care Maintenance in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

Patients with chronic liver disease are at risk for severe complications if they develop acute hepatitis and should be vaccinated against HAV and HBV if they are not immune. Nonresponse to vaccinations is more common in patients with cirrhosis, and postvaccination immunity should be assessed. Patients with chronic liver disease should receive annual influenza vaccination and recommended pneumococcal vaccinations. Other vaccinations should be given based on current recommendations (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine).

Patients with cirrhosis should be counseled to avoid the use of alcohol. Sedating medications such as opiates and benzodiazepines should be avoided because they can precipitate symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy. Raw shellfish can transmit Vibrio vulnificus, which can be fatal in patients with cirrhosis; therefore, patients with cirrhosis should be counseled to avoid the consumption of raw shellfish.

Patients with cirrhosis should be screened for osteoporosis. Cholestasis results in decreased absorption of vitamin D, and all causes of cirrhosis can be associated with osteoporosis. The cause of osteoporosis in patients with cirrhosis is multifactorial and is associated with jaundice, hypogonadism, and decreased levels of insulin-like growth factor that are common in cirrhosis. Patients with osteoporosis should be treated with bisphosphonates. Patients with esophageal varices should receive intravenous rather than oral bisphosphonates. Patients with identified osteopenia should be treated with supplemental calcium plus vitamin D. Weight-bearing exercise should be encouraged in all patients with cirrhosis.

Protein-calorie malnutrition is common in patients with cirrhosis. Protein consumption is essential to prevent the catabolic effects of chronic liver disease. Daily protein intake of 1.5 g/kg body weight should be administered to patients with chronic liver disease.

Medications that are metabolized by the liver may require dosage adjustments depending on the severity of the cirrhosis. Patients with advanced cirrhosis (CTP class B or C) often require dosage adjustments, whereas patients with well-compensated cirrhosis (CTP class A) may not.

Hepatic Tumors, Cysts, and Abscesses

Benign liver masses are typically discovered incidentally on abdominal imaging. These findings are usually asymptomatic, with the exception of liver abscesses or lesions greater than 5 cm in size. Most liver lesions can be characterized and diagnosed noninvasively with CT or MRI. Percutaneous fine-needle aspiration of lesions is reserved for cases in which imaging is nondiagnostic and in which the information obtained will prompt a change in management. Risks associated with liver biopsy, including a 1% risk for serious complication, such as bleeding or perforation, and a 1-in-10,000 risk for death, need to be considered.

Hepatic Cysts

Hepatic cysts are a common radiological finding on abdominal imaging. Simple cysts are smooth with thin walls and anechoic features on ultrasonography. Patients with polycystic liver disease or autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease can present with numerous liver cysts. Asymptomatic cysts are benign and require no follow-up. Large cysts, rarely presenting with abdominal pain, can be treated with surgical defenestration or, when surgery is contraindicated, with cyst aspiration and sclerotherapy. Rarely, polycystic liver disease with extensive cystic liver involvement may lead to portal hypertension and/or malnutrition. Obstruction of the portal vein or inferior vena cava can occur due to mass effect. Options for management include surgery, and if that is not technically feasible, liver transplantation. Cystadenomas with thick, irregular walls can be distinguished from simple cysts by ultrasonography; they require surgical resection due to risk for malignancy.

Hepatic Adenomas

Hepatic adenomas are rare liver neoplasms. Despite the benign nature of these lesions, adenomas that are greater than 5 cm in size have potential for risk for hemorrhage or malignant transformation. Hepatic adenomas are associated with oral contraception use and occur eight times more frequently in women than in men. Other risk factors include androgen treatment, type 1 and 3 glycogen storage disease, and obesity. Increasingly, hepatic adenoma is an incidental finding on abdominal ultrasound, CT, or MRI. Hepatic adenomas can be differentiated from focal nodular hyperplasia using MRI with gadobenate dimeglumine or gadoxetate disodium contrast. Biopsy is indicated when there is diagnostic uncertainty but may increase the risk for bleeding; therefore, it should only be performed if the diagnosis will result in a meaningful change in management. Hepatic adenomas 5 cm in size or smaller can be managed with serial imaging every 6 months for a 2-year period. For patients with hepatic adenomas larger than 5 cm in size, the risk for hemorrhage or malignant transformation is elevated and surgical resection should be considered.

Oral contraceptives should be discontinued in all patients with hepatic adenomas with follow-up CT or MRI at 6- to 12-month intervals to confirm stability or regression in the size of the lesion. The duration of surveillance depends on subsequent imaging findings. Biopsy to risk-stratify hepatic adenomas can be considered on a case-by-case basis. Hepatic adenomas with β-catenin activation are at higher risk for malignant transformation into hepatocellular carcinoma. Men with hepatic adenomas are at increased risk for malignant transformation, and resection is recommended.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia is the most common benign liver tumor and a frequent incidental finding. It is caused by a congenital arterial anomaly leading to a focal area of regeneration that can cause the formation of a stellate scar seen on CT or MRI. CT or MRI with and without contrast is recommended to confirm the diagnosis. Focal nodular hyperplasia does not have malignant potential or a risk for bleeding and does not require follow-up. In women with focal nodular hyperplasia who continue to use oral contraceptives, there is limited evidence to recommend liver ultrasonography every 2 to 3 years to assess for growth. MRI with a hepatobiliary contrast agent can be used to distinguish between focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatic adenomas.

Hepatic Hemangiomas

Hepatic hemangiomas are common and more frequent in women. Up to 20% of affected patients have multiple hemangiomas. In most cases, symptoms that might be ascribed to hemangioma are due to other causes. Kasabach-Merritt syndrome is a rare syndrome that develops with particularly large hemangiomas that develop consumptive coagulopathy with thrombocytopenia and sometimes disseminated intravascular coagulation. Hemangiomas do not have potential for malignancy, and spontaneous bleeding is rare. The diagnosis should be confirmed with MRI or CT with contrast, which typically shows peripheral nodular enhancement and progressive centripetal fill-in. Biopsies should be avoided due to bleeding risk. Hepatic hemangiomas are benign lesions that do not require intervention or follow-up except in the rare instance when they cause symptoms.

Hepatic Abscesses

Pyogenic Liver Abscesses

Pyogenic liver abscesses are complications of biliary tract infections or portal venous spread of intra-abdominal infections such as diverticulitis. Patients with pyogenic liver abscesses present with fever, right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain, and malaise. Liver abscesses are typically polymicrobial, and the diagnosis is confirmed by radiologically guided aspiration. Small abscesses (<3 cm) can be successfully treated by administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Larger abscesses are treated by aspiration or longer-term percutaneous tube drainage in addition to broad-spectrum antibiotics. The success of radiologically guided aspiration and tube drainage has resulted in only rare need for surgical excision of pyogenic hepatic abscesses.

Amebic Liver Abscesses

Amebic abscesses of the liver are found in developing areas of the world or in migrants from countries in which amebiasis is endemic. Intestinal infection with amoebae can result in invasion of the portal vein and migration to the liver. Typical symptoms of amebic liver abscesses include right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain and fever. Hepatic imaging and serological testing make the diagnosis of amebic liver abscess. Treatment of the hepatic infection with metronidazole or tinidazole should be accompanied by eradication of the coexistent intestinal infection with paromomycin.

Liver Transplantation

Referral for liver transplantation is indicated in patients whose MELD score is 15 or greater because liver transplantation provides a survival advantage in these patients. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis, including ascites, esophageal variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, or hepatocellular carcinoma, should also be considered for referral. Patients should generally abstain from alcohol for at least 6 months, although transplant centers may differ in their requirements for sobriety duration and chemical-dependency treatment. Other factors important in candidate selection are adequate social support, adherence to treatment, and absence of significant cardiopulmonary, psychiatric, and active infectious diseases.

Appropriate candidates are placed on the national waiting list, with the highest priority given to patients with acute liver failure and high MELD-Na scores. In some conditions, the most common being hepatocellular carcinoma, exception points are added to the MELD score, resulting in increased scores every 3 months. Other conditions eligible for MELD exception points include portopulmonary hypertension, hepatopulmonary syndrome, familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, primary hyperoxaluria, cystic fibrosis, and cholangiocarcinoma.

The average 1- and 5-year survival rates after liver transplantation are 92% and 75% to 85%, respectively. Recipients require lifelong immunosuppression, most commonly using tacrolimus, and less often, cyclosporine. Both drugs are metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A isozymes and pose a risk for drug-drug interactions. Recipients are at increased risk for developing diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and malignancy secondary to immunosuppressive medications.

Pregnancy-Related Liver Diseases

During pregnancy, physiological changes occur that mimic chronic liver disease. Altered hormonal states and increasing circulatory volume can lead to lower-extremity edema, palmar erythema, and spider angiomata.

In pregnant women with preexisting chronic liver disease, HBV and HCV can be transmitted to the newborn. There are no specific steps that can be taken to eliminate the risk for vertical transmission of HCV; however, vertical transmission is relatively rare, with less than 5% of women with HCV viremia transmitting the virus to their children.

HBV carries a higher risk for vertical transmission. Among women with replicating HBV infection, the vertical transmission rate can be as high as 90%. Pregnant women with an HBV DNA level greater than 200,000 IU/mL between gestational weeks 24 and 28 should start oral antiviral treatment to prevent vertical transmission. Oral antiviral agents approved in pregnancy include lamivudine, telbivudine, and tenofovir. Breastfeeding is not contraindicated during treatment. Passive immunization with HBV immune globulin and active HBV vaccination should be administered to newborns within 12 hours of delivery. These measures can reduce vertical transmission rates by 95%. Administration of antiviral medications in the third trimester to pregnant women with high HBV viremia can further reduce the risk for vertical transmission.

Women with autoimmune hepatitis who become pregnant typically continue the use of prednisone and/or azathioprine, which are generally felt to be safe during pregnancy.

Several diseases of the liver are unique to pregnancy and can affect the health of both the mother and fetus. During the first trimester, hyperemesis gravidarum occurs when prolonged, intractable vomiting results in fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. Elevated hepatic transaminase levels are seen in up to 50% of cases of hyperemesis gravidarum, but jaundice is rare. Laboratory abnormalities typically resolve when vomiting abates. Pyridoxine and antiemetic medications can resolve symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is presumed to result from cholestatic effects of increased levels of pregnancy-related hormones. Increased risk for this condition can be seen in women of South American descent, twin pregnancies, and in women with a history of liver disease. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy typically presents in the second to third trimesters of pregnancy. Symptoms include pruritus in most patients and jaundice in 10% to 25% of patients. Serum bile acid levels are elevated and help to establish the diagnosis. Fetal complications, including placental insufficiency, premature labor, and sudden fetal death, are more common in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Ursodeoxycholic acid produces relief of pruritus and results in biochemical improvement, but it does not improve fetal outcomes. Increased fetal mortality is noted to occur late in gestation. Delivery is typically induced at 36 to 38 weeks of gestation in women with proven disease.

The most serious pregnancy-related liver diseases occur in the third trimester of pregnancy and are associated with high rates of maternal and fetal mortality. In these conditions, the only definitive therapy is delivery of the fetus. HELLP (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, and Low Platelets) syndrome is a severe complication of preeclampsia. HELLP typically presents with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea with vomiting, pruritus, and jaundice. Rates of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality are high. Patients with HELLP syndrome should, therefore, be managed in high-risk obstetrical units. Blood pressure, fluid and electrolytes, kidney function, and coagulopathy may require careful management in the perinatal state. Although delivery is the definitive therapy for HELLP syndrome, the maternal condition may continue to worsen in the immediate postpartum period. Resolution is typically seen within days after delivery. Rarely, liver transplantation may be required if liver recovery is not seen. HELLP can reoccur in as many as 25% of subsequent pregnancies.

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is a rare but serious condition that also occurs late in pregnancy. It presents with symptoms similar to those of HELLP syndrome. Women with this condition typically present with a 1- to 2-week history of nausea and vomiting, right-upper-quadrant or epigastric pain, headache, jaundice, anorexia, and/or polyuria and polydipsia (due to associated transient diabetes insipidus). Indicators of liver failure, including hypoglycemia and coagulopathy, are often worse in acute fatty liver of pregnancy than in HELLP syndrome; both conditions require close monitoring to prevent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is a potential cause of acute liver failure. Affected patients may require transfer to a liver transplant center. Prompt delivery of the fetus once the diagnosis is recognized typically results in improvement of the mother's medical condition within 48 to 72 hours. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy can reoccur in subsequent pregnancies. It is also associated with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, and affected women and their offspring should be screened for this deficiency.

Vascular Diseases of the Liver

Portal Vein Thrombosis

Portal vein thrombosis is common in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and is a consequence of poor flow through the portal veins rather than hypercoagulability; it may occasionally occur in patients without cirrhosis. The diagnosis is typically established by abdominal Doppler ultrasonography; contrast-enhanced CT or MRI should be completed to delineate the extent of thrombosis and to assess for tumor thrombosis. Chronic portal vein thrombosis is typically asymptomatic and does not usually require anticoagulation therapy unless thrombophilia, bowel ischemia, or progression of thrombus is present. Patients with acute portal vein thrombosis should receive anticoagulation unless the risk of bleeding is very prohibitive. Non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants or low-molecular-weight heparin are the anticoagulants of choice. Systemic thrombolytic therapy and catheter-directed thrombolysis are rarely indicated.

Budd-Chiari Syndrome

Budd-Chiari syndrome describes any disease process that obstructs the normal outflow of blood from the liver, usually as thrombosis of the hepatic veins. Causes vary, but it may occasionally be associated with hypercoagulable states such as in patients with a myeloproliferative neoplasm, pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, IBD, or inherited thrombophilias. Underlying malignancy, especially hepatocellular carcinoma, must be considered. Typical symptoms of Budd-Chiari syndrome include hepatomegaly, ascites, and right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain. Budd-Chiari syndrome is typically diagnosed by ultrasound with Doppler evaluation in the appropriate clinical setting. The caudate lobe of the liver is hypertrophied due to the presence of venous outflow channels distinct from the hepatic veins. Long-term anticoagulation is required in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome, although bleeding risks are significant in patients with acute or chronic liver disease, portal hypertension, and esophageal varices. Angioplasty of the hepatic veins and/or TIPS placement can be used to reestablish adequate hepatic venous drainage. If liver failure develops, liver transplantation should be considered.