Disorders of the Adrenal Glands

- related: Endocrine

- tags: #endocrine

Adrenal Anatomy and Physiology

Although considered one organ, the adrenal glands have two functionally distinct regions: an outer cortex and an inner medulla. The cortex secretes hormones that are classified as mineralocorticoid (aldosterone), glucocorticoid (cortisol), and androgen (dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA]). The medulla secretes catecholamines.

The adrenal cortex is composed of three zones: the zona glomerulosa (outer), zona fasciculate (middle), and zona reticularis (inner). Aldosterone production in the zona glomerulosa is regulated by the renin-angiotensin system and promotes sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion across the distal tubule of the kidney. The resultant expansion of extracellular volume increases blood pressure. Aldosterone also has direct inflammatory and fibrotic effects on other organs that are independent of its effects on blood pressure. Major stimuli to aldosterone secretion include hypotension, hypovolemia, and hyperkalemia.

Cortisol production in the zona fasciculata is regulated by release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland. Cortisol exhibits a distinct diurnal rhythm characterized by peak levels on awakening that decrease to very low levels by bedtime. Superimposed on this diurnal rhythm are small oscillations of cortisol secretion while awake. Most cortisol circulates in the blood attached to cortisol-binding protein, with only a small fraction circulating as biologically active, free hormone. Cortisol is crucial to the body's adaptive response to physiologic stress, and levels increase in response to psychological stress, as well as physical illness. Cortisol actions are diverse and include immune, vascular, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic effects.

DHEA, produced in the zona reticularis, and its sulfate DHEAS, are weak adrenal androgens that mediate their effects through peripheral conversion to testosterone. In women the adrenal gland is a significant contributor to circulating androgen levels. In men the adrenal contribution to androgen effect is negligible.

The adrenal medulla secretes the catecholamines norepinephrine and epinephrine in response to hypotension, hypoglycemia, fear, anxiety, acute illness, and other causes of psychological and physical stress. Catecholamines interact with α- and β-adrenergic receptors to increase pulse and blood pressure, relax smooth muscle, dilate bronchioles, and increase metabolic rate. A small fraction of norepinephrine and epinephrine is excreted in the urine as free hormone; the rest is degraded in the liver to metanephrine and normetanephrine prior to urinary excretion.

Adrenal Hormone Excess

Cortisol Excess (Cushing Syndrome Due to Adrenal Mass)

Cortisol-secreting adrenal adenomas and, rarely, carcinomas account for 20% of endogenous causes of Cushing syndrome. Excess cortisol secretion from these tumors suppresses ACTH production from the pituitary gland, resulting in a form of Cushing syndrome classified as ACTH-independent. ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome is more common and is most commonly caused by pituitary adenomas (see Disorders of the Pituitary Gland). While many of the symptoms and signs of Cushing syndrome are common in the general population, some, including supraclavicular fat pads, proximal muscle weakness, facial plethora, and wide violaceous striae (Figure 3), are considered more discriminatory (see Disorders of the Pituitary Gland). Diagnosis of Cushing syndrome is challenging because patients present along a spectrum ranging from mild disease with subtle findings to severe, life-threatening disease. In addition, hypercortisolemia from psychological stress and physical illness can also occur in the absence of Cushing syndrome. In severe stress states such as major depression, anxiety, psychosis, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and severe visceral obesity, a pseudo-Cushing state may occur in which hypercortisolemia and nonspecific clinical features of Cushing syndrome coexist.

Evaluation for Cushing syndrome in patients without specific signs of Cushing syndrome is not recommended.

The evaluation of Cushing syndrome involves (1) initial testing followed by confirmatory testing for Cushing syndrome; (2) determining Cushing syndrome as ACTH-independent or -dependent; and (3) localizing the source of ACTH in ACTH-dependent disease or confirming the presence of adrenal mass (or masses) in ACTH-independent disease. It is imperative that biochemical Cushing syndrome be confirmed with certainty prior to looking for the source, as misdiagnosis may lead to unnecessary testing and treatment.

The diagnosis of Cushing syndrome necessitates a combination and repetition of tests (Figure 4). Measurement of morning or random serum cortisol is unreliable, due to overlap of serum cortisol levels among normal patients, those with Cushing syndrome, and those with mild hypercortisolism/pseudo-Cushing state in the absence of Cushing syndrome. In addition, total cortisol levels are unreliable when binding proteins are affected by oral estrogen, acute illness, and low protein states.

Initial tests for Cushing syndrome have similar diagnostic accuracy and include measurement of 24-hour urine free cortisol, serial late night salivary cortisols, and the 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test. When suspicion for Cushing syndrome is low, a single test, if negative, makes Cushing syndrome unlikely. When there is a higher index of suspicion for Cushing syndrome, two different initial tests are recommended.

Urine free cortisol and late night salivary cortisol represent the serum free cortisol fraction and avoid pitfalls in interpretation related to changes in cortisol-binding proteins. Spurious elevation of urine free cortisol can result from hypercortisolemia not related to Cushing syndrome/pseudo-Cushing state or when significant polyuria (>5 L/d) is present. False-negative results can occur in advanced kidney disease or in patients with variable secretory rates of cortisol.

Late-night salivary cortisol is collected at home by the patient between 11 PM and midnight on at least two different nights. This test assesses for the normal diurnal rhythm of cortisol, which is lost in Cushing syndrome, and the cortisol level will not be low as expected. This test is not recommended in patients who do shift work or have an inconsistent sleep pattern. Recent cigarette smoking or contamination of the sample by topical glucocorticoids can falsely increase results.

The 1-mg (low-dose) dexamethasone suppression test depends on the principle that autonomous cortisol secretion is not subject to feedback suppression with exogenous glucocorticoids. Dexamethasone is taken at 11 PM and serum total cortisol is measured at 8 AM the following morning. A post-dexamethasone cortisol level of greater than 5 µg/dL (138 nmol/L) is considered a positive test. A lower cut-off cortisol value of greater than 1.8 µg/dL (49.7 nmol/L) has been advocated to improve test sensitivity, but this occurs at the expense of reduced specificity. False-positive results may occur with concomitant use of medications (carbamazepine, phenytoin, and pioglitazone) that induce hepatic CYP3A4 enzymes and accelerate dexamethasone metabolism. Simultaneous measurement of serum dexamethasone can confirm patient adherence or altered dexamethasone metabolism.

Many factors can raise cortisol levels in the absence of Cushing syndrome, so test interpretation should incorporate the pretest probability of Cushing syndrome. A urine free cortisol level greater than 3 times the upper normal range in the setting of clinical manifestations of Cushing syndrome is considered diagnostic of the disorder, whereas a positive test in the setting of low suspicion for Cushing syndrome does not support the diagnosis. If initial testing is positive, confirmation and further evaluation should involve consultation with an endocrinologist. Once the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome is established, the next step is measurement of ACTH; if suppressed (<5 pg/mL [1.1 pmol/L]) indicating an ACTH-independent cause of Cushing syndrome, a dedicated adrenal CT or MRI is indicated. If adrenal glands appear normal on imaging, the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome should be questioned.

Surgical resection is the definitive treatment for benign and malignant cortisol-secreting adrenal tumors.

Following adrenalectomy, patients require daily hydrocortisone therapy to allow recovery from prolonged ACTH suppression due to hypercortisolism. Recovery of adrenal fasciculate function may take up to 1 year or longer depending on the severity of Cushing syndrome (see Disorders of the Pituitary Gland).

Primary Aldosteronism

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is a common cause of secondary hypertension. Traditionally, hypokalemia was considered to be a biochemical prerequisite for the diagnosis of PA, but it is now recognized that more than 60% of patients have normal potassium levels. As hypertension is often the only sign of primary aldosteronism, the condition frequently goes undiagnosed. Identification of patients with primary aldosteronism is important because aldosterone has deleterious effects on the cardiovascular system and treatment prevents progression and can sometimes reverse changes. Higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality have been noted in patients with primary aldosteronism compared to those with primary hypertension with similar blood pressure control. The potential health impact of untreated primary aldosteronism and the importance of recognizing primary aldosteronism is reflected in updated guidelines on case-detection testing for primary aldosteronism (Table 24).

Primary aldosteronism is caused by hyperplasia of both adrenal glands (idiopathic hyperaldosteronism) in two-thirds of cases, and a unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) in one-third of cases. The diagnosis of primary aldosteronism involves performing stepwise case detection, as well as confirmatory and localization studies. The most reliable case-detection test is calculation of an plasma aldosterone-plasma renin ratio (ARR) by measuring plasma aldosterone concentration and plasma renin activity (or direct renin concentration) in a mid-morning seated sample. In patients taking an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, renin should be elevated, so in these patients, a simple initial test is plasma renin activity measurement. If the plasma renin activity is suppressed, the likelihood of primary aldosteronism is high and an ARR should be performed; if not, hyperaldosterone state is ruled out. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (spironolactone and eplerenone) and high-dose amiloride can significantly interfere with interpretation of ARR and should be discontinued 6 weeks prior to evaluation.

Other antihypertensive agents can be continued, but because some may have minor effects on aldosterone and/or renin levels (Table 25), the results of the ARR should be interpreted with these effects in mind. Hydralazine, a selective α-adrenergic receptor blocker, and slow-release verapamil have minimal effects on aldosterone and renin secretion, and they can be substituted when feasible for other agents if the ARR is equivocal. An ARR greater than 20 with a plasma aldosterone concentration of at least 15 ng/dL (414 pmol/L) is considered a positive result, and patients should be referred to an endocrinologist, who may perform additional testing to confirm inappropriate aldosterone secretion in a salt-replete state.

The localization study of choice for primary aldosteronism is a dedicated adrenal CT. Findings may include normal adrenal glands or unilateral or bilateral adenoma(s)/hyperplasia. In one third of patients, the CT may not identify the cause of primary aldosteronism because some APAs are too small to see or there is an incidental adrenal mass unrelated to primary aldosteronism. Consequently, most patients with confirmed primary aldosteronism should undergo adrenal vein sampling to confirm the source of the hyperaldosteronism.

Medical therapy with an aldosterone receptor antagonist (spironolactone or eplerenone) is the treatment of choice for primary aldosteronism due to idiopathic hyperaldosteronism, or when patients with APA are not candidates for, or do not wish to undergo, surgery. Spironolactone is often preferred over eplerenone because it is less expensive and more potent. However, patients on spironolactone are more likely to develop dose-dependent side effects of gynecomastia and erectile dysfunction in men and menstrual irregularities in women. Hypokalemia almost always resolves with treatment, but blood pressure control may require additional agents. No studies clearly show superiority of adrenalectomy compared to medical therapy for APA, but surgery may be more cost-effective in the long term.

Laparoscopic adrenalectomy is effective for unilateral disease and reduces plasma aldosterone and its attendant increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Hypertension is improved in most patients and cured in about 40% of patients. Persistent hypertension following adrenalectomy may be due to vascular changes caused by chronic hypertension or coexistent primary hypertension. Patients are more likely to achieve resolution of hypertension if they were taking fewer than three antihypertensive agents preoperatively, and if they have one or fewer first-degree relatives with hypertension. Serum potassium should be monitored weekly for the first month postoperatively, and patients should be instructed to eat a high-salt diet due to risk of hyperkalemia from transient reduction in aldosterone production in the remaining adrenal gland due to chronic suppression of the renin-angiotensin system during the period of hyperaldosteronism. Short-term mineralocorticoid replacement is required in those patients who develop hyperkalemia.

Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are catecholamine-secreting tumors that arise from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla (80%) and extra-adrenal (mostly abdominal) sympathetic ganglia, respectively. Tumors can also arise from parasympathetic ganglia in the head and neck, but these rarely secrete catecholamines.

At least one-third of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas are associated with a germline mutation. Pheochromocytomas may occur in familial syndromes including multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1 (Table 26). All patients with catecholamine-secreting tumors should, therefore, be offered genetic counseling.

Hypertension associated with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma can show a sustained pattern, with or without paroxysms, or occur as paroxysms only. Some patients (10% to 15%) remain normotensive. The classic triad of palpitations, headache, and diaphoresis is seen in fewer than 50% of patients with pheochromocytoma. Multiple symptoms related to catecholamine excess can occur including abdominal pain, skin pallor, blurred vision, or polyuria. Rarely, patients can present with acute myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, or stroke.

Indications for testing for pheochromocytoma are shown in Table 24. Initial tests for pheochromocytoma include measurement of plasma-free metanephrine collected in a supine position or 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrine and catecholamine levels. Elevation in catecholamines can occur in patients under psychological or physical stress. Medications can affect results (Table 27) and should be discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to testing. Accurate diagnosis is further confounded by the fact that patients with or without hypertension may have adrenergic-type spells in the absence of a catecholamine-secreting tumor. Interpretation of the test results must consider the extent of metanephrine elevation rather than whether the result is normal or abnormal. Mild elevations may require repeat testing. Levels more than four times the upper limit of normal, in the absence of acute stress or illness, are consistent with a catecholamine-secreting tumor. The plasma-free metanephrine is highly sensitive (96% to 100%). The specificity is 85% to 89%. Urine fractionated metanephrine and catecholamines have higher specificity (98%) and high sensitivity (up to 97%). Neither test is superior, so clinicians can use an estimate of pretest probability to select the initial test. When there is a high index of suspicion, plasma-free metanephrine is chosen, and when suspicion is low, urine fractionated metanephrine and catecholamines may be a better option.

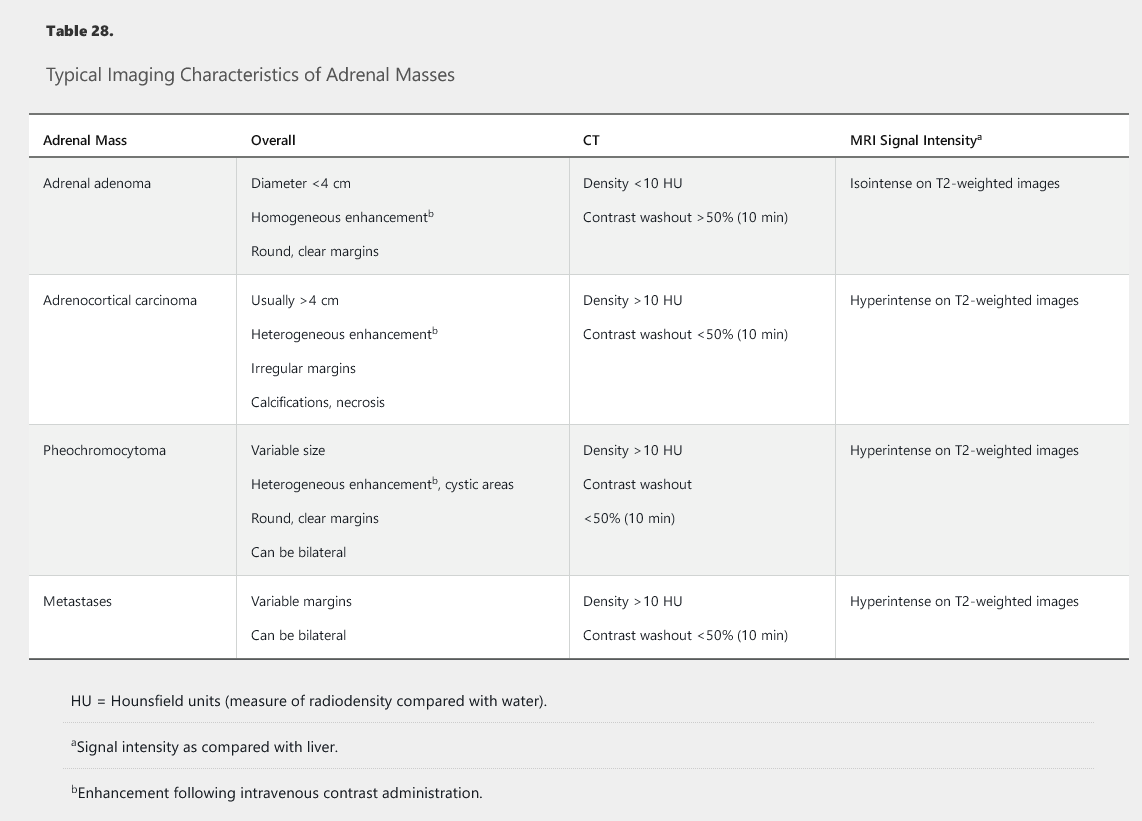

The search for a tumor should begin when a biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma is supported by laboratory results, to avoid misdiagnosing an incidental nonfunctioning adrenal mass as a pheochromocytoma. It is difficult to determine clinical relevance of significantly elevated metanephrine levels in hospitalized patients. The imaging modality of choice is an abdominal and pelvic contrast-enhanced CT as 85% of catecholamine-secreting tumors are intra-adrenal (and 95% reside in the abdomen or pelvis). Typical imaging features of pheochromocytomas are shown in Table 28. The average size of a symptomatic pheochromocytoma at diagnosis is 4 cm. If the CT is negative, reconsidering the diagnosis is the first step; however, if suspicion of a catecholamine-secreting tumor is high, the next step is iodine 123 (123I)-metaiodobenzylguanidine scanning. This test may also be indicated in patients with very large pheochromocytomas (>10 cm) to detect metastatic disease or paragangliomas to detect multiple tumors. Fludeoxyglucose-position emission tomography is more sensitive for detection of metastatic disease, but its use is generally reserved for those patients with established malignant tumors.

The definitive treatment for pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma is surgical resection. Preoperative α-receptor blockade with phenoxybenzamine for 10 to 14 days before surgery is essential to prevent hypertensive crises during surgery. The dose is progressively increased to achieve a blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg or less and pulse of 60 to 70/min seated, and systolic pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher with pulse of 70 to 80/min standing. Side effects include dizziness, nasal congestion, and fatigue. To facilitate dose escalation and mitigate the volume contraction effects of α-receptor blockade, patients are instructed to liberalize their salt and fluid intake. A β-blocker is added once α-blockade is achieved to manage reflex tachycardia, but it should never be started prior to adequate α-blockade because unopposed α-adrenergic vasoconstriction can result in a hypertensive crisis.

For large pheochromocytomas with a high hormone secretion rate, other agents such as a calcium channel blocker and/or metyrosine are added to the treatment regimen. Calcium channel blockers can also be used in patients who develop significant hypotension on small doses of α-blocker. Selective α-1 receptor blockers such as doxazosin can be used as an alternative to phenoxybenzamine if availability or lack of insurance coverage of the latter is a problem. Postoperatively, patients can have significant hypotension, and most require fluid and vasopressor support at least briefly in the postoperative period. Patients with pheochromocytoma may have impaired fasting glucose or type 2 diabetes related to insulin resistance induced by catecholamine excess. This can improve or reverse following adrenalectomy.

Approximately 83% of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas are benign. Pathologic findings do not predict which tumors will become malignant and develop metastases. Since metastases can occur decades after the initial diagnosis, patients should undergo long-term annual biochemical screening, typically with plasma-free metanephrine.

Androgen-Producing Adrenal Tumors

Androgen-producing adrenal tumors are rare and lead to menstrual irregularities and virilization in women including hirsutism, voice-deepening, increased muscle mass, increased libido, and clitoromegaly. Tumors secrete DHEA/DHEAS and androstenedione, which are subsequently converted to testosterone in the periphery. DHEAS-secreting tumors of the adrenal gland are readily visible on CT imaging, and adrenal vein sampling to localize the tumor is rarely required. Approximately 50% are benign, and the treatment of choice is resection.

Adrenal Hormone Deficiency

Primary Adrenal Insufficiency

Causes and Clinical Features

Primary adrenal insufficiency (AI) is a life-threatening disorder that often presents with insidious onset of symptoms making diagnosis a challenge (Table 29). It may also present as adrenal crisis, often precipitated by an acute illness or the initiation of thyroid hormone replacement in a patient with unrecognized chronic AI. Although skin hyperpigmentation from stimulation of melanocytes by high ACTH levels is considered a hallmark of primary adrenal insufficiency, it is not present in approximately 5% patients. The most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency is autoimmune destruction of all layers of the adrenal cortex leading to progressive mineralocorticoid, glucocorticoid, and adrenal androgen deficiency. Most patients have positive 21-hydroxylase antibodies, and approximately 50% will develop another autoimmune endocrine disorder in their lifetime (primary hypothyroidism, primary ovarian insufficiency, celiac disease, hypoparathyroidism, or type 1 diabetes mellitus).

Primary adrenal insufficiency can also be caused by infiltrative disorders such as infection (tuberculosis, fungal infections), sarcoidosis, and lymphoma, which result in bilateral adrenal gland enlargement. Metastatic disease involving the adrenals, most commonly from lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma rarely leads to adrenal insufficiency even if both adrenal glands are involved.

Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage can present as acute adrenal insufficiency and should be considered if unexpected hypotension develops. Risk factors for bilateral adrenal hemorrhage include protein C deficiency, anticoagulation, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and sepsis.

Diagnosis

An algorithm for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is outlined in Figure 5. Initial evaluation includes the measurement of morning serum total cortisol and ACTH levels. Primary adrenal insufficiency is confirmed by the combination of low serum cortisol and elevated serum ACTH levels. Important considerations in the interpretation of the results are shown in Figure 5 and often require referral to an endocrinologist. Additional evaluation may include measurement of 21-hydroxylase antibodies; positive 21-hydroxylase antibodies are found in approximately 90% of autoimmune adrenalitis cases. If negative, CT scan of the adrenal glands should be obtained.

Treatment

Both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid therapy is required for treatment of primary AI. The preferred glucocorticoid is hydrocortisone taken 2 or 3 times daily. Adherence to multiple daily doses can be challenging so prednisone can be used as an alternative (Table 30). The principle of replacement is to administer a higher dose in the morning and to avoid replacement in the evening. Despite this attempt to mimic diurnal variation, patients with primary AI report a decrease in health-related quality of life. It is imperative to avoid overreplacement with glucocorticoid, to avoid iatrogenic Cushing syndrome with its risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, bone loss, and cardiovascular disease. Some patients “feel better” at higher than physiologic replacement doses, but the risks outweigh the benefits of supraphysiologic doses. Mineralocorticoid replacement is achieved with daily fludrocortisone. DHEAS replacement is controversial in women due to lack of robust data for benefit and concerns regarding the safety and quality of U.S. preparations, which are supplements and not regulated as drugs.

Patients cannot mount an appropriate increase in cortisol with illness, and therefore, instruction in “sick day” rules is essential to prevent adrenal crisis (Table 31). For minor physiologic stress states such as respiratory infection, fever, or minor surgery under local anesthesia, patients should double or triple their baseline glucocorticoid dose for 2 to 3 days. Higher doses of glucocorticoid are required during moderate or major physiologic stress. Patients who present with adrenal crisis should receive fluid resuscitation and an initial immediate dose of intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg), followed by intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg) every 8 hours for the next 24 hours, with subsequent dosing governed by clinical status. Patients with concomitant untreated adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism should always receive glucocorticoid replacement therapy first to prevent precipitation of adrenal crisis by thyroid hormone replacement. Patients should also be counselled to wear a medic-alert identification at all times. No increase in mineralocorticoid dose is necessary with illness.

The term “adrenal fatigue” is used by some alternative medicine providers to represent a constellation of symptoms purported to occur in patients who experience chronic emotional or physical stress that are claimed to be caused by simultaneous hyper- and hypocortisolism. There is no scientific evidence to support such a condition. Patients may undergo salivary cortisol testing, but interpretation of the results is often unreliable. Some patients labeled with “adrenal fatigue” are given hydrocortisone therapy or animal-derived adrenal gland extract that may contain active glucocorticoid, leading to exogenous suppression of ACTH production and iatrogenic Cushing syndrome. Sudden discontinuation of these products can lead to acute adrenal insufficiency. Patients with “adrenal fatigue” should be carefully tapered off any glucocorticoid therapy and other potential causes for their symptoms explored.

Adrenal Function During Critical Illness

During times of physiologic stress, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is stimulated to produce increased levels of cortisol. In some patients, the increase in cortisol secretion is thought to be suboptimal and termed “relative AI.” There is debate, however, as to whether the entity of relative adrenal insufficiency is a true disease. Cortisol-binding globulin and albumin decrease in critical illness, lowering the measured total cortisol. There is no agreement on a set of diagnostic criteria for relative AI despite the ability to measure free cortisol, calculated free cortisol, and basal and ACTH-stimulated total cortisol level in critically ill patients. Studies to date do not show improved survival in patients with relative AI treated with high-dose glucocorticoid therapy. Reversal of shock, however, may be improved, and hence it is currently recommended that stress-dose hydrocortisone be administered to patients with shock that is resistant to standard fluid and vasopressor therapy.

Adrenal Mass

Incidentally Noted Adrenal Masses

An adrenal incidentaloma is defined as an adrenal mass greater than 1 cm in diameter that is detected on imaging performed for purposes other than suspicion of adrenal disease. The prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma increases with age and is estimated to be approximately 10% in those 70 years of age or older. Most lesions are benign, nonfunctioning adenomas, and approximately 10% to 15% secrete excess hormones. Other causes include metastases (probability increases if known primary malignancy), myelolipoma, cysts, and adrenocortical carcinoma.

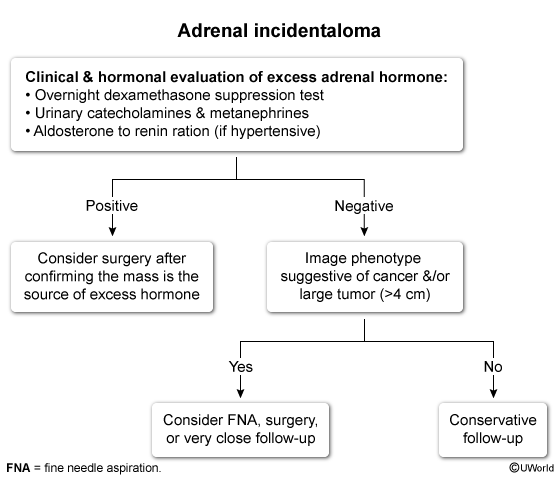

The finding of an incidental adrenal mass prompts two main questions: (1) Is it secreting excess hormone (aldosterone, cortisol, or catecholamines)? and (2) Is it benign or malignant? Patients with hypertension or with hypokalemia require testing for primary aldosteronism. Biochemical testing for pheochromocytoma, such as a 24-hour urine total metanephrine measurement, should be undertaken in all patients, even in the absence of typical symptoms or hypertension.

All patients should also be evaluated for subclinical Cushing syndrome, a condition characterized by ACTH-independent cortisol secretion that may result in metabolic (hyperglycemia and hypertension) and bone (osteoporosis) effects of hypercortisolism, but not the more specific clinical features of Cushing syndrome, such as supraclavicular fat pads, wide violaceous striae, facial plethora, and proximal muscle weakness. Initial testing for subclinical Cushing syndrome is achieved with a 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test, with a cortisol level greater than 5 µg/dL (138 nmol/L) considered a positive test. Following a positive result, further tests are required to confirm cortisol autonomy and may include measurement of ACTH (suppressed), DHEAS (low), 24-hour urine free cortisol, and an 8-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test; referral to an endocrinologist is recommended at this point. The decision whether to proceed to adrenalectomy should take into account the risks versus benefits of surgery. Studies to date have not been robust enough to show clear postoperative improvement in clinically important outcomes but suggest improved glucose, lipid, blood pressure, and bone density measurements.

Imaging findings can help differentiate between a benign and a malignant adrenal mass (see Table 28).

CT findings that suggest malignancy include bilateral or large (>4 cm) lesions, irregular or inhomogeneous morphology, contrast enhancement with delayed contrast washout (> 50% contrast retention seen 10 minutes after contrast administration), and high radiographic attenuation. Attenuation is expressed in Hounsfield units (HU), which are an estimate of the radiodensity of a lesion. Low-attenuation lesions (<10 HU) typically have a high lipid content and are usually benign adenomas; high-attenuation lesions (>20 HU) are more likely to represent adrenal metastasis, adrenocortical carcinoma, or pheochromocytoma. This patient's lesion has high attenuation but otherwise benign features (eg, unilateral, round, <4 cm).

Most adrenocortical carcinomas measure more than 4 cm at the time of discovery. Approximately 75% of benign adrenal masses, however, are also in this size range. Approximately 66% of benign adenomas are lipid-rich and exhibit low attenuation (<10 HU) on CT imaging. Benign adrenal adenomas also exhibit rapid washout (>50%) of contrast material compared to non-benign lesions. Adrenal biopsy has a limited role in evaluation of incidentalomas and is reserved for lesions suspicious for metastases or an infiltrative process such as lymphoma or infection. Pheochromocytomas should be ruled out prior to biopsy to avoid the possibility of a hypertensive crisis. Biopsy should not be performed when there is suspicion for primary adrenocortical carcinoma because, without review of the whole specimen, pathology cannot reliably distinguish this from a benign cortical adenoma, and tumor seeding is possible. If the former is suspected, the diagnosis should be established by adrenalectomy.

An algorithm for management of adrenal incidentaloma, including monitoring of lesions that do not require adrenalectomy, is shown in Figure 6.

Adrenocortical Carcinoma

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare, aggressive tumor that often secretes excess cortisol and/or androgens. Patients may present with rapid onset of Cushing syndrome, with or without virilization and/or symptoms from mass effect, such as increased abdominal girth and lower extremity edema. Fifty percent of ACCs secrete cortisol; 20% secrete multiple hormones, including cortisol and aldosterone precursors; and less than 10% secrete aldosterone. Some ACCs are discovered as an incidental adrenal mass that is either indeterminate or suspicious for ACC (see Table 28). Lesions are often large (>4 cm), and disease is at an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis. For localized disease, first-line therapy includes open resection. Debulking surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy may also be options for palliation in advanced ACC.

Mitotane is an adrenolytic agent commonly used as adjuvant therapy that has been shown to be associated with longer recurrence-free survival. Mitotane causes primary AI, and daily glucocorticoid replacement therapy is required, often in supraphysiologic doses, due to mitotane-induced accelerated metabolism of glucocorticoids. Some patients also develop aldosterone deficiency manifested by hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, elevated renin levels, and postural hypotension, requiring fludrocortisone replacement. Five-year survival rates range from 62% to 82% for those with disease confined to the adrenal gland and 13% for tumors associated with distant metastases.