Disorders of Spinal Cord

- related: Neurology

- tags: #neurology

Presenting Symptoms and Signs of Myelopathy

Myelopathy (any disorder involving the spinal cord) arises from extrinsic (external compression) and intrinsic (intramedullary) pathologic causes. Recognition and treatment of spinal cord injury in a timely manner is crucial, given the vital anatomy contained within this small-diameter structure.

Determining the location and mechanism of injury is crucial for rapidly deciding on the accurate site and type of neuroimaging required and the kind of specialty consultation (such as neurosurgical) needed. Spinal cord injury often presents with symptoms and signs at or below the site of a lesion. Corticospinal tract injury results in spastic paresis or paralysis, with weakness, hyperreflexia, muscle spasticity, and extensor plantar responses. There is often loss of sensation at or below the site of injury. Performance of a detailed sensory examination, with ascending pinprick testing throughout the entire torso and neck, is essential. Gait is abnormal in most patients with myelopathy; a sensory ataxia or spastic gait sometimes can be an isolated presenting sign. Involvement of the distal spinal cord and lower roots (cauda equina syndrome) results in decreased muscle tone, areflexia, and loss of perianal sensation.

Many patients with myelopathy report pain at the level of the compressive disease. Squeezing or banding sensations around the chest or abdomen near the level of spinal cord compression may be reported. Focal tenderness to percussion over the spinal column may be elicited. Disruptions in bowel and bladder function and loss of sphincter tone also are often noted. These varied symptoms may lead to unnecessary cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, or urinary tract evaluations and to a delayed diagnosis.

Compressive Myelopathy

Clinical Presentation

Spinal cord compression often presents with neck or back pain, followed by weakness, sensory changes, and bladder or bowel dysfunction. Examination typically reveals upper motor neuron signs (weakness, spasticity, hyperreflexia, and extensor planar responses), but lower motor neuron signs (atrophy, hyporeflexia) sometimes can occur near the level of compression. Specific signs and symptoms can provide clues as to the cause of compression. The presence of fever and focal back pain and tenderness, especially in patients who have had recent back instrumentation or have a history of intravenous drug use, may indicate an epidural abscess (see MKSAP 18 Infectious Disease for more information on cranial and spinal epidural abscesses). A history of neoplasia and focal back pain should raise concern for metastatic disease (Figure 26) or pathologic vertebral fracture. Anticoagulant use raises the risk of compression from an epidural hematoma, particularly in the setting of recent back instrumentation.

Patients with chronic spinal stenosis due to osteoarthritic degenerative spinal disease frequently present with chronic myelopathic symptoms. Compressive myelopathy should thus be considered in older patients with gait dysfunction or weakness. Degenerative spinal disease often affects the cervical and lumbar regions, but thoracic cord involvement is quite rare. Most patients with chronic compressive myelopathy initially report progressive leg weakness, spasticity, distal numbness, and bladder impairment. Some with lumbar stenosis describe symptoms similar to vascular claudication (pseudoclaudication), with exertional groin, thigh, or buttock pain, and possibly also of weakness or numbness.

Diagnosis

Initial MRI of the spinal cord at the suspected region of injury is the preferred means of diagnosing compressive myelopathy and will often reveal the cause. Imaging should be performed emergently in cord compression thought to be secondary to abscess or malignancy because neurologic compromise can progress rapidly. CT myelography can show compressive myelopathy when MRI is not feasible but often does not reveal the cause of compression. Additionally, this type of imaging may be difficult to arrange emergently and is problematic in patients with allergies to contrast dyes or impaired kidney function.

Treatment

Surgical decompression is typically required to treat spinal cord compression, but medical therapies can complement surgical treatment, depending on the underlying cause. Emergent treatment usually is indicated because the most important indicator of long-term neurologic function is the neurologic function at the time of decompression. Neurologic function is rarely regained as a result of therapy, but further deterioration may be prevented.

Adjunctive therapy is important; an epidural hematoma may first require management of the bleeding diathesis, and cord compression caused by epidural abscess requires antibiotics. The use of glucocorticoids in traumatic spinal cord compression is controversial. They generally are not indicated with hematoma and abscess. A joint panel of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons has argued against the use of high-dose glucocorticoids in acute spinal cord trauma, given the lack of definitive evidence of benefit and some evidence of potential harm. Despite these recommendations, this issue remains controversial, and many physicians still offer glucocorticoid treatment for this select patient population because of the lack of alternative beneficial strategies.

Spinal cord compression from metastatic disease requires emergent use of high-dose glucocorticoids and urgent surgical decompression, followed by radiation for most tumor types. Clinical trials have shown the superiority of surgical decompression in optimizing ambulation. Certain radiosensitive tumor types, such as leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, and germ cell tumors, may not require initial surgical decompression and instead may be treated urgently with radiation therapy. Surgical intervention also is sometimes deferred in patients with a completed neurologic deficit, patients with a poor prognosis or functional status, and patients without a distinct neurologic deficit. For more information on spinal cord compression due to metastatic disease, see MKSAP18 Hematology and Oncology.

For chronic cervical or lumbar stenosis or acute disk herniation, symptomatic management can control symptoms in most patients. Surgical decompression may be required for patients with myelopathy refractory to medical management. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for more information about treating musculoskeletal pain.

Noncompressive Myelopathy

Noncompressive myelopathy can be caused by many inflammatory, infectious, metabolic, vascular, and genetic disorders. Inflammatory causes are most common, including multiple sclerosis (see Multiple Sclerosis), neuromyelitis optica, and sarcoidosis.

Idiopathic Transverse Myelitis

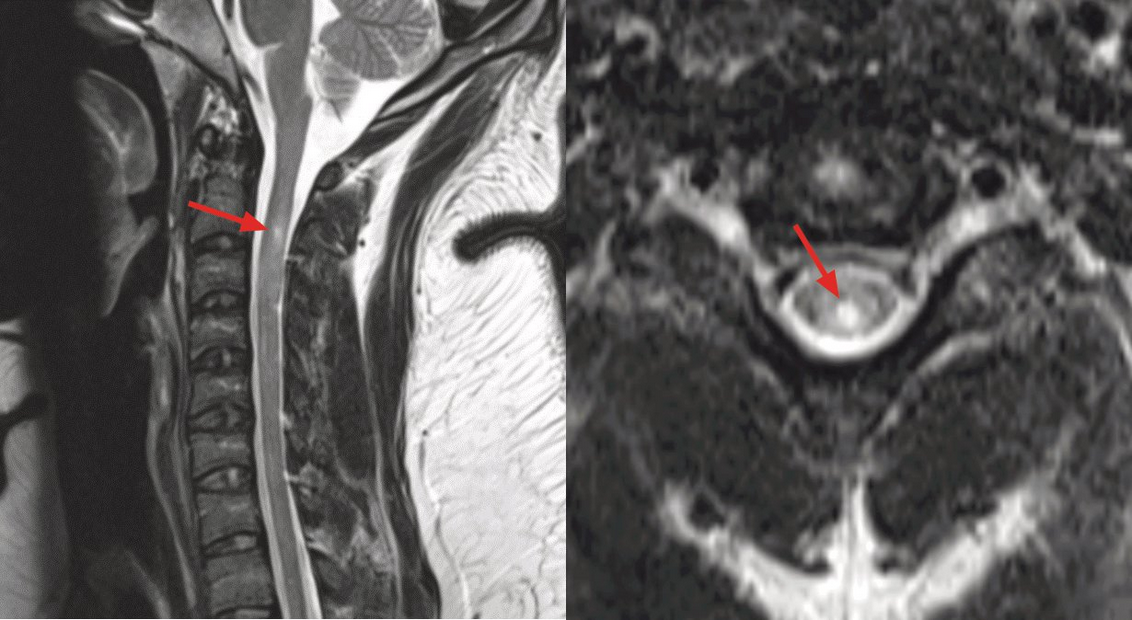

Idiopathic transverse myelitis (ITM) (Figure 27) is a monophasic, inflammatory, and demyelinating disorder of the spinal cord. ITM typically affects only one region of the spinal cord and is considered to be a para- or postinfectious inflammatory response. Affected patients frequently experience subacute weakness, sensory changes, and bladder or bowel dysfunction. Some patients experience an initial prodrome of back pain or a thoracic banding sensation.

MRI of the cervical spine in a patient with transverse myelitis. Sagittal T2-weighted (left) and axial T2-weighted (right) images both demonstrate hyperintensity within the parenchyma of the spinal cord (red arrows).

MRI of the cervical spine in a patient with transverse myelitis. Sagittal T2-weighted (left) and axial T2-weighted (right) images both demonstrate hyperintensity within the parenchyma of the spinal cord (red arrows).

The diagnostic criteria for ITM require presence of clinical features of the syndrome, evidence of inflammation (either cerebrospinal fluid leukocytosis or contrast enhancement on spinal cord MRI), and exclusion of other potential causes. Those with complete myelitis (symptoms referable to complete rather than partial cord transection), a lack of elevated oligoclonal bands or IgG index in the cerebrospinal fluid, and no lesions on brain MRI are much more likely to have ITM than other disorders, such as multiple sclerosis. This is a crucial distinction because ITM is not a recurrent disorder and does not require long-term immunomodulatory therapy. Recurrence of symptoms or new symptoms beyond a 30-day period should arouse suspicion for multiple sclerosis or other recurrent disorders.

The consensus-based treatment of ITM is intravenous methylprednisolone, 1 g/d for 3 to 7 days. This therapy is intended to stop inflammatory damage of the spinal cord and allow for recovery of neurologic function. Patients whose disease is refractory to glucocorticoids may benefit from plasmapheresis or cyclophosphamide.

Infectious causes of transverse myelitis should always be considered when evaluating patients for possible ITM. Herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, West Nile virus, human T-lymphotropic virus, Lyme disease, and neurosyphilis infections can affect the spinal cord. HIV infection can cause a transverse myelitis–like syndrome at the time of seroconversion or result in a chronic degenerative vacuolar myelopathy in patients with chronic low CD4 cell counts. Mycobacterium tuberculosis can infect the meninges and spinal cord and present with a transverse myelitis-like syndrome. Treatment should be directed against a particular infection if present. The addition of glucocorticoids to treat these disorders is controversial but may be indicated when infections are associated with significant spinal cord edema.

Subacute Combined Degeneration

Severe and prolonged vitamin B12 deficiency can result in subacute combined degeneration, which refers to a dysfunction of the corticospinal and dorsal sensory tracts of the spinal cord that manifests as spastic paresis with reduced vibration and position sense and ataxia. MRI can show increased signal in the affected white-matter pathways without associated inflammatory changes. Laboratory study results show a low serum vitamin B12 level with elevated levels of serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine. Macrocytic anemia may be present, but the neurologic manifestations of B12 deficiency may precede development of anemia. The clinical symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency can sometimes occur with low-normal serum B12 levels, and thus supportive laboratory studies should be performed in patients with a high index of clinical suspicion. Vitamin B12 replacement usually halts progression of the disease but may not necessarily reverse existing symptoms.

Nitrous oxide abuse also can cause a relative vitamin B12 deficiency that results in subacute combined degeneration. Supplementation of vitamin B12 in those circumstances without cessation of the drug may impede improvement in symptoms.

Copper deficiency (due to malabsorption, nutritional deficiency, or zinc toxicity) can also cause subacute combined degeneration. This entity should be considered in patients with suggestive symptoms who have normal vitamin B12 levels. Myelopathy from such nutritional deficiencies should specifically be considered in patients with previous bariatric surgical procedures.

Vascular Disorders

Infarcts in the territory of the anterior spinal artery typically present as sudden-onset flaccid paralysis with preservation of vibration and position sense because of the lack of dorsal column involvement. Prolonged hypotension during cardiovascular or aortic surgery can also sometimes result in lack of perfusion to watershed regions of the spinal cord, especially in the area where the anterior spinal artery meets the most prominent radicular artery (artery of Adamkiewicz) in the upper thoracic cord.

Dural arteriovenous fistulas of the spinal vascular supply can either result in chronic myelopathy due to venous congestion or cause infarction of the cord due to altered vascular dynamics or thromboses. Fistulas are most common in men older than 50 years and in persons with previous spinal surgery. Abnormal vascular flow voids often are seen on careful review of spinal MRIs. Diagnosis is often challenging and typically requires digital subtraction angiography of all radicular vessels along the entire spine.

Genetic Disorders

Although rare, several genetic disorders can result in chronic myelopathy. Some of these disorders have clear familial inheritance, but others may result from de novo mutations. Hereditary spastic paraplegia comprises hereditary disorders that result in chronic, progressive, ascending weakness and spasticity, often beginning in childhood or adolescence. Genetic screening is available, but no treatment currently exists. Female carriers of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy sometimes develop adrenomyeloneuropathy, a degenerative condition of the spinal cord and peripheral nerves. These patients can be diagnosed through alterations in the serum very-long-chain fatty acid profiles or genetic testing. Genetic counseling is indicated in such settings.