Diseases of the Aorta

- related: Cardiology

- tags: #cardiology

Introduction

Diseases of the aorta include chronic conditions, such as thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms and aortic atheromas, and potentially life-threatening acute conditions, such as aortic dissection and aneurysm rupture. Once chronic aortic diseases are diagnosed, surveillance and treatment are critical to prevent disease progression, complications, and mortality.

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm

Thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) is defined as an increase in the thoracic aortic diameter of greater than 50% relative to the expected or normal aortic dimension. TAAs may occur at the level of the aortic root, ascending aorta, aortic arch, or descending aorta. They most commonly involve the aortic root and ascending aorta, often forming at the site of aortic atherosclerosis. TAAs are usually the result of cystic medial degeneration and weakening of the aortic wall due to loss of smooth muscle fibers and elastic fiber degeneration.

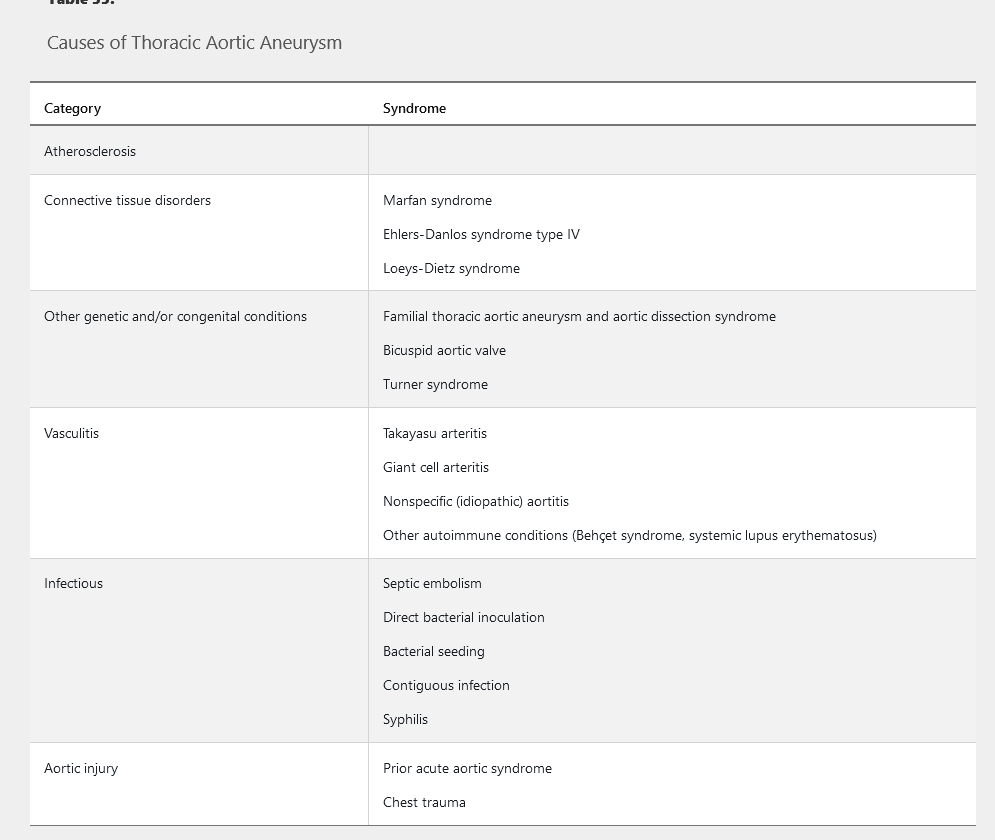

Common causes of TAA are summarized in Table 33. TAAs that occur in patients younger than 50 years are often caused by connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Bicuspid aortic valve morphology is also an important risk factor for TAA formation; TAAs occur in approximately 50% of patients with a bicuspid aortic valve. Other risk factors for TAA include age and hypertension.

TAAs are often asymptomatic and are commonly detected by echocardiography during an evaluation of left ventricular function or murmurs. Infrequently, symptoms of hoarseness and dysphagia occur when an aneurysm compresses surrounding structures. Physical examination findings, such as a diastolic heart murmur or wide pulse pressure, are found in the setting of aortic regurgitation, which often occurs in combination with TAA. If the aneurysm ruptures, patients present with severe chest or back pain, sudden shortness of breath, or sudden cardiac death.

Screening and Surveillance

Screening for abnormalities of the thoracic aorta with aortic imaging is indicated in asymptomatic patients with genetic conditions (such as Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), a bicuspid aortic valve, or a family history of TAA or aortic dissection. Screening is not recommended in other asymptomatic persons.

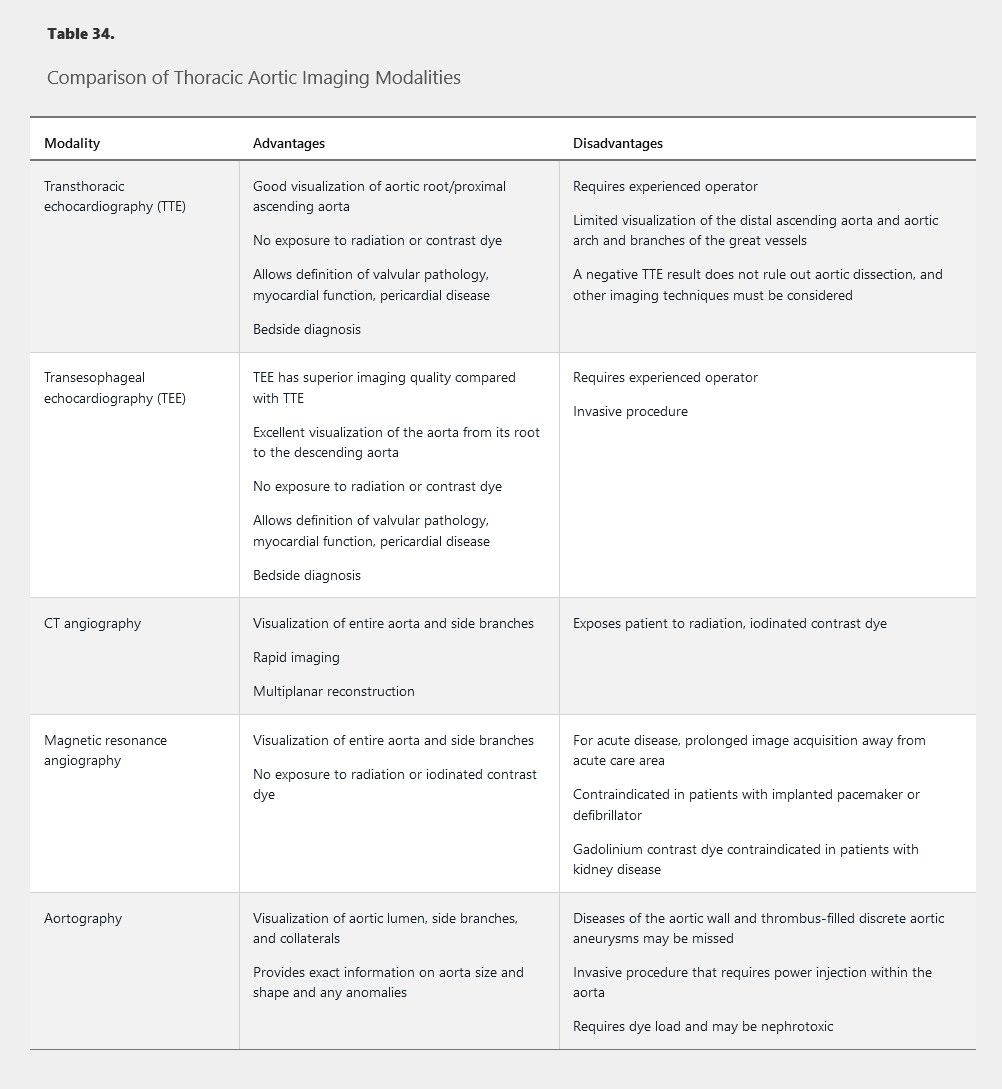

After TAA is detected, noninvasive imaging is indicated to determine aortic cross-sectional area (Table 34). Aortic diameter measurement often varies substantially depending on the type of imaging study used. Care must be taken to measure the dimension perpendicular to the long axis of the aorta because oblique measurements may overestimate the true aortic diameter. The maximum aortic diameter at the site of an aneurysm (measured in cm) is generally used in the criteria for surveillance and treatment.

Because the leading cause of death in patients with TAA is rupture, surveillance and treatment depend on the aneurysm size and risk for rupture. Once the diameter of the aneurysm has grown larger than 5.0 cm, the average growth rate is 0.1 cm/year, and risk for rupture increases. Additional independent risk factors for rupture are a rapid rate of expansion (>0.5 cm/year), the presence of an aneurysm during pregnancy, and previous aortic dissection. Annual surveillance is appropriate in patients with a first-degree relative with a history of familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection.

Transthoracic echocardiography is most commonly used for annual surveillance of TAAs smaller than 5.0 cm in diameter. In patients with previous rapid rate of expansion or in patients with a TAA of 5.0 cm in diameter or larger, more frequent surveillance is often warranted. Patients with rapid expansion of the TAA or aortic dimension of 5.5 cm should undergo additional imaging with CT angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).

In patients with a TAA and a genetic condition (Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) or bicuspid aortic valve, it is recommended that repeat assessment occur 6 months after diagnosis to determine the rate of enlargement. Thereafter, annual imaging is recommended if the aortic diameter has been stable and smaller than 4.5 cm. If the aortic diameter is 4.5 cm or larger or the rate of enlargement exceeds 0.5 cm/year, imaging should be performed every 6 months.

Treatment

TAAs with a diameter smaller than 5.0 cm can usually be managed with medical therapy and active surveillance. Medical therapy includes aggressive blood pressure control with a goal blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg. β-Blockers are the preferred antihypertensive agents in patients with TAA. In patients with Marfan syndrome, β-blockers and losartan have been associated with a reduced rate of aneurysm growth.

Once ascending aortic aneurysm size exceeds 5.5 cm in diameter, repair is warranted to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with aneurysm rupture. In patients with an ascending aorta or aortic root greater than 4.5 cm in diameter who require coronary artery bypass grafting or surgery to repair valve pathology, aortic repair should be performed at the time of cardiac surgery. Current guidelines recommend that all patients with a bicuspid aortic valve and ascending aortic aneurysm undergo aortic repair when the aneurysm exceeds 5.5 cm in diameter, unless there is an indication to repair concomitant coronary artery disease or aortic valve pathology. In patients with Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend that patients undergo aortic repair at a lower threshold (4.5-5.0 cm).

The aneurysm location, associated aortic valve pathology, and presence of concomitant coronary artery disease all dictate the type of thoracic aortic repair performed. Open surgical repair is indicated for TAAs that involve the aortic root, ascending aorta, and aortic arch. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) with stent grafting should be used when a descending aortic aneurysm has a diameter greater than 6.0 cm, has exhibited rapid growth (>0.5 cm/year), or has caused end-organ damage, owing to a lower morbidity and shorter hospital stay relative to open repair. TEVAR has the advantage of avoiding an open surgical operation, although complications (stroke, spinal ischemia, aortic graft endoleaks) can occur.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as an abnormal dilatation of the aorta with an anteroposterior diameter greater than 3.0 cm. Risk factors include male sex (6:1 male-to-female incidence ratio), advanced age, smoking, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and a family history of AAA.

Screening and Surveillance

AAA is most commonly diagnosed incidentally by CTA or abdominal ultrasonography. Approximately 75% of patients with AAA are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Because of the high mortality rate associated with aneurysm rupture, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends one-time screening with duplex ultrasonography in all men aged 65 to 75 years who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and selective screening in men in this age group who have never smoked (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine).

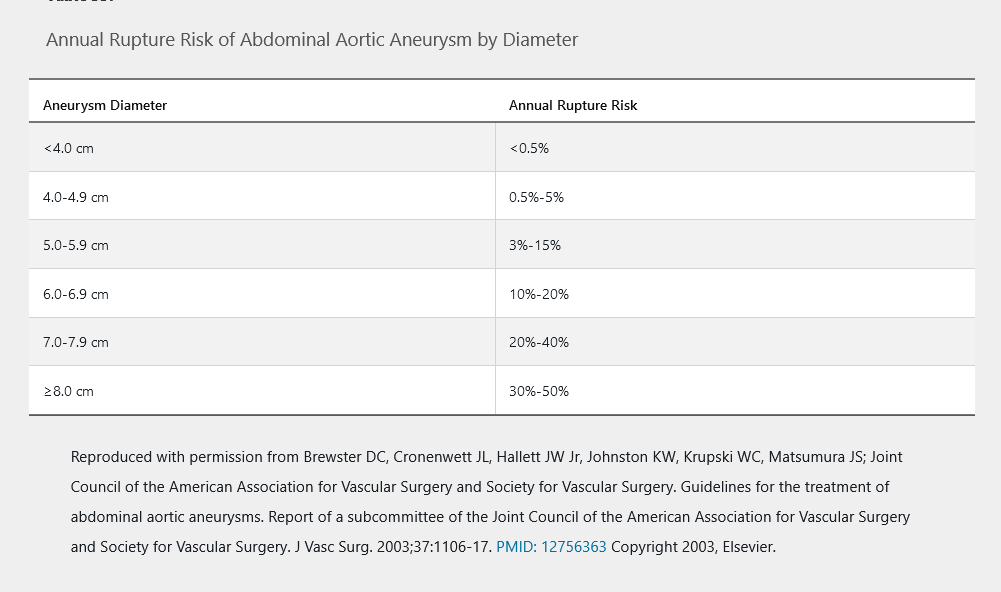

Estimated annual risk for aortic rupture according to AAA dimension is shown in Table 35. In patients with an AAA diameter of 4.0 cm or less, surveillance with duplex ultrasonography every 2 to 3 years is warranted. In patients with an AAA diameter of 4.1 to 5.4 cm, surveillance with CTA or duplex ultrasonography should be performed every 6 to 12 months. Once the aortic diameter meets the threshold for aortic repair, anatomic imaging tests, such as CTA or MRA, are indicated to determine the exact location of the AAA (suprarenal, juxtarenal, or infrarenal) in planning for repair.

Treatment

Medical treatment of AAA involves risk factor reduction to reduce the risk for rupture, cardiovascular morbidity, and overall mortality. Aortic repair should be performed in patients with an AAA diameter of 5.5 cm or larger, in those with rapid expansion in AAA size (>0.5 cm/year), and in patients presenting with symptoms resulting from AAA (abdominal or back pain/tenderness). In patients with an indication for aortic repair, the choice between open surgical repair and endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is driven by the location of the AAA and involvement of the renal and mesenteric arteries. Suprarenal and juxtarenal aneurysms most often necessitate open surgical repair. Patient age, comorbid conditions, and ability to tolerate open surgical repair determine which procedure should be performed in patients with an infrarenal AAA. EVAR is associated with lower short-term (30-day) morbidity and mortality but no significant differences in long-term mortality. Additionally, EVAR is associated with increased need for repeat intervention and significantly higher rates of endoleak, device failure, and postimplantation syndrome (fever, leukocytosis, elevated serum C-reactive protein). These complications necessitate diligent follow-up with noninvasive imaging tests (CTA or ultrasonography) to evaluate the stent graft.

Aortic Atheroma

Aortic atherosclerotic plaques commonly occur in patients with evidence of atherosclerosis in other vascular beds. The most frequent complication of aortic atheromas is systemic embolism and stroke. Aortic atheromas greater than 4 mm in diameter or with a mobile component are more likely to be associated with thromboembolism compared with smaller atheromas.

Aortic atheromas are most frequently detected as an incidental finding on imaging studies. The presence of an aortic atheroma represents a coronary artery disease risk equivalent, and patients should be considered for antiplatelet and statin therapies in addition to other risk factor interventions.

Acute Aortic Syndromes

The most common and life-threatening acute aortic syndromes include acute aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm rupture. Additional acute aortic syndromes include intramural aortic hematoma and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer.

Pathophysiology

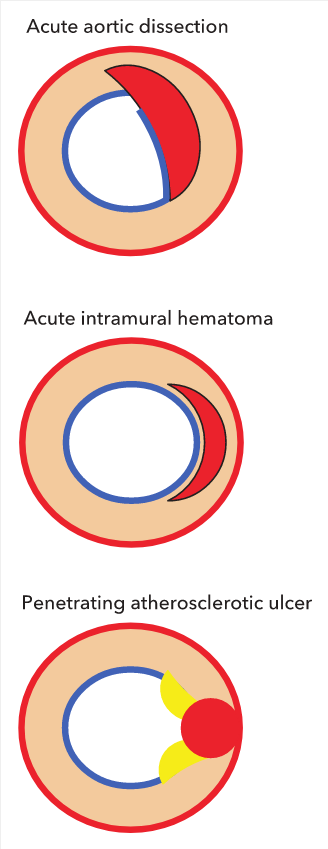

Acute aortic dissection involves tearing of the aortic intima, leading to passage of blood from the true lumen of the aorta into a false lumen (Figure 40). Dissection of the aorta can propagate in an antegrade or retrograde fashion, mainly due to shear forces. Propagation of the dissection can result in cardiac tamponade; acute aortic regurgitation; compromise of arterial side branches (carotid, mesenteric, renal, or iliac arteries); and underperfusion of organs such as the brain, intestines, or kidneys. Aortic dissections are categorized according to their location of origin by use of the Stanford classification, which describes type A dissections as originating within the ascending aorta or arch and type B dissections as originating distal to the left subclavian artery. Type A aortic dissections require surgical intervention due to risk for rupture and death, whereas type B aortic dissections can often be initially managed with medical stabilization and blood pressure control.

Cross-sectional representation of acute aortic syndromes. Acute aortic dissection: interruption of intima (blue) with creation of an intimal flap and false lumen formation within the media (red). Color flow by Doppler echocardiography or intravenous (IV) contrast by CT is present within the false lumen in the acute phase. Acute intramural hematoma: crescent-shaped hematoma contained within the media without interruption of the intima (blue). No color flow by Doppler echocardiography or IV contrast by CT within crescent. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer: atheroma (yellow) with plaque rupture disrupting intimal integrity; blood pool contained within intima-medial layer (pseudoaneurysm). Color flow by Doppler echocardiography or IV contrast by CT enters the ulcer crater.

Cross-sectional representation of acute aortic syndromes. Acute aortic dissection: interruption of intima (blue) with creation of an intimal flap and false lumen formation within the media (red). Color flow by Doppler echocardiography or intravenous (IV) contrast by CT is present within the false lumen in the acute phase. Acute intramural hematoma: crescent-shaped hematoma contained within the media without interruption of the intima (blue). No color flow by Doppler echocardiography or IV contrast by CT within crescent. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer: atheroma (yellow) with plaque rupture disrupting intimal integrity; blood pool contained within intima-medial layer (pseudoaneurysm). Color flow by Doppler echocardiography or IV contrast by CT enters the ulcer crater.

Intramural aortic hematomas result from microtears in the aortic intima and rupture of the vasa vasorum (Figure 41). Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers are caused by erosion of the internal elastic membrane at the site of aortic atherosclerotic plaque, leading to a blood-filled false space within the wall of the aorta (Figure 42). Both intramural hematomas and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers are more common in type B dissections.

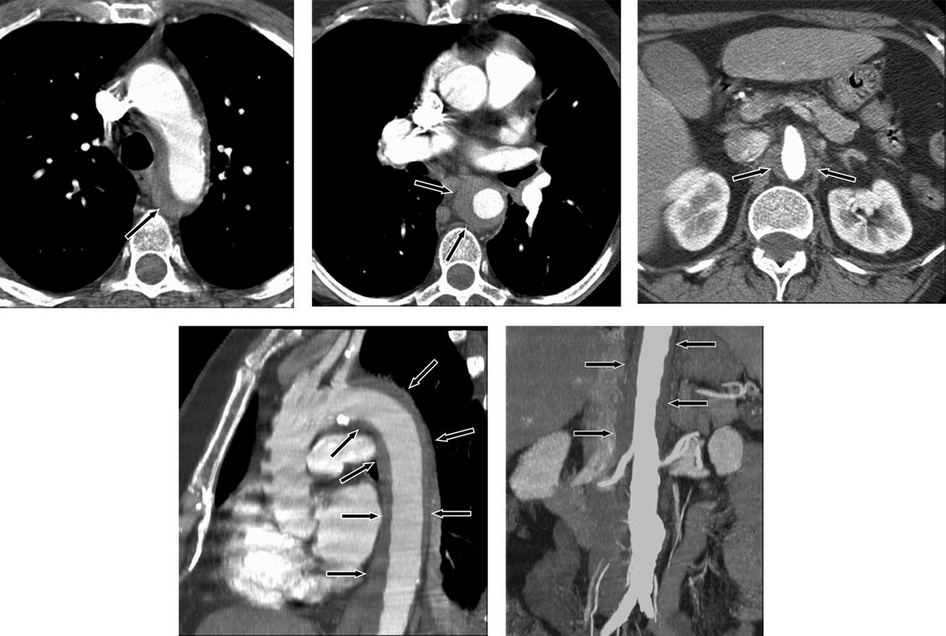

Intramural hematoma demonstrated as a low-attenuation band of hematoma (arrows) in the aortic wall on CT images. Axial images at the level of the aortic arch (top left), through the mid thorax (top middle), and at the level of the superior mesenteric artery with narrowing of the aortic lumen (top right). Oblique sagittal reformatted image through the thorax (note band artifact evident without the use of electrocardiographic gating) (bottom left). Coronal reformatted image through the abdomen demonstrates the length of the hematoma and an incidental infrarenal aortic aneurysm (bottom right).

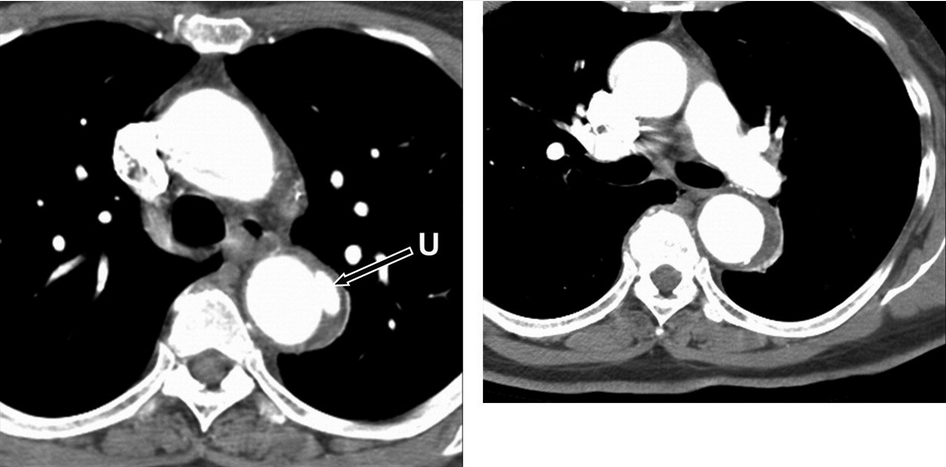

Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of the proximal descending thoracic aorta. Axial CT images at the level of the aortopulmonary window (left) and at the level of the left pulmonary artery (right) demonstrate a small penetrating ulcer (arrow) that extends beyond the expected confines of the aortic lumen with adjacent intramural hematoma both at the level of the ulcer itself and that extends a few centimeters caudally in the wall of the descending thoracic aorta. U = penetrating ulcer.

Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of the proximal descending thoracic aorta. Axial CT images at the level of the aortopulmonary window (left) and at the level of the left pulmonary artery (right) demonstrate a small penetrating ulcer (arrow) that extends beyond the expected confines of the aortic lumen with adjacent intramural hematoma both at the level of the ulcer itself and that extends a few centimeters caudally in the wall of the descending thoracic aorta. U = penetrating ulcer.

Diagnosis and Evaluation

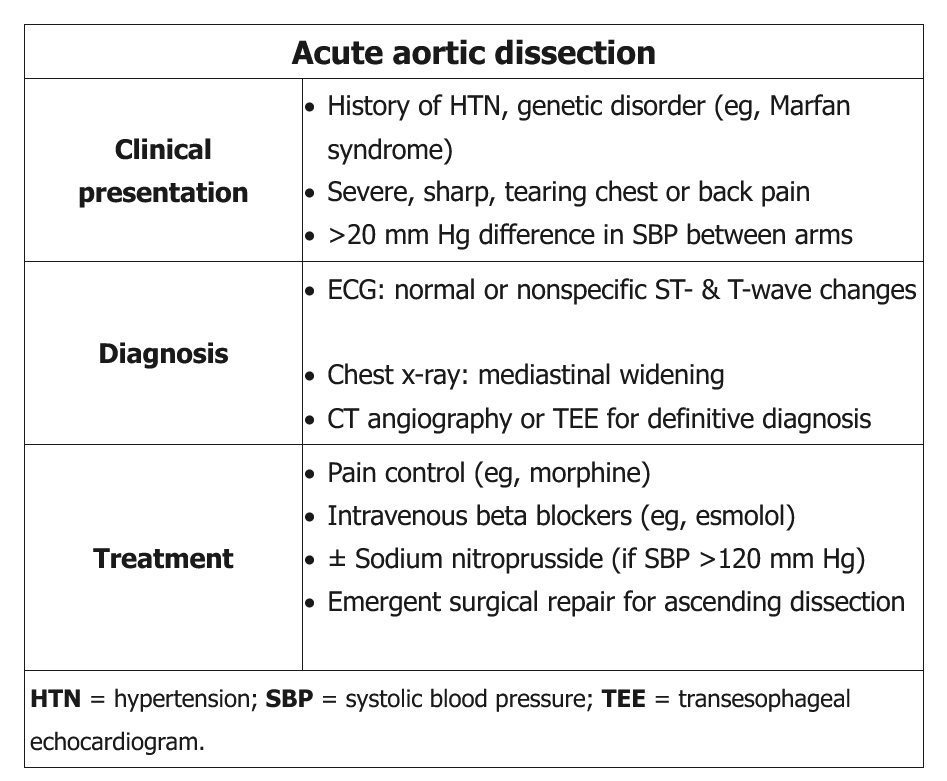

The abrupt onset of sharp, severe chest pain in this patient with evidence of long-standing hypertension (ie, audible S4, high-voltage QRS complexes suggesting left ventricular [LV] hypertrophy) and a murmur of acute aortic regurgitation (decrescendo diastolic murmur) strongly suggests acute aortic dissection. A pulse deficit or significant systolic blood pressure (SBP) difference (>20 mm Hg) between extremities is absent in approximately two-thirds of presenting patients.

Acute aortic dissection is a medical emergency, and a high index of suspicion is needed for immediate diagnosis and treatment. It classically presents with the sudden onset of chest or back pain that has a tearing or ripping quality; however, not all patients will have this symptom. Patients may present with hypertension, syncope, a murmur of aortic regurgitation, or heart failure in the setting of sudden aortic insufficiency. The findings of asymmetric blood pressures in the upper extremities, asymmetric pulses, or pulsus paradoxus should all raise suspicion for acute aortic dissection.

Abnormalities may be present on chest radiography (widened mediastinum) and electrocardiography (ST-segment depression), but these findings are not diagnostic for acute aortic dissection. In patients with a high likelihood of acute aortic dissection, diagnostic imaging tests should not be delayed based on the results of chest radiography, electrocardiography, or laboratory testing.

Transesophageal echocardiography, CTA, and MRA have similar sensitivity and specificity in patients with acute thoracic aortic disease. Transthoracic echocardiography is often used but is limited by the inability to image the distal ascending aorta, transverse aortic arch, and descending aorta. Compared with CTA or MRA, the primary advantages of transesophageal echocardiography in patients suspected of having aortic dissection include its portability for an unstable patient and the lack of iodinated contrast. With the increased availability of CTA, it has become the primary diagnostic test for acute thoracic aortic disease. Invasive aortography is rarely indicated for the diagnosis of acute disease; however, it is indicated at the time of endovascular repair or when noninvasive testing is contraindicated or cannot be performed.

Treatment

Patients with acute aortic dissection without evidence of cardiogenic shock should be treated with medical therapy to control heart rate and reduce blood pressure. Current guidelines recommend reducing systolic blood pressure to 120 mm Hg or less in the first hour in patients with aortic dissection. Intravenous β-blockers are first-line treatment; for hypertension that does not completely respond to β-blockers, intravenous vasodilators (nitroprusside, nicardipine) should be administered. Pain control is often necessary and is best accomplished with intravenous opioids.

Hydralazine is a direct arterial vasodilator that can cause reflex sympathetic stimulation, leading to increased heart rate, LV contractility, and aortic wall shear stress. As a result, its use should be avoided in patients with suspected aortic dissection.

Nitroprusside is also a potent vasodilator that can cause reflex sympathetic stimulation; however, due to a short half-life and relative ease in titration, it is the preferred drug for additional blood pressure control in patients with acute aortic dissection who have persistent SBP elevation despite initial antihypertensive therapy. In such patients, nitroprusside (typically administered for SBP >120 mm Hg) should be given only after adequate beta blockade due to the risk of reflex sympathetic stimulation.

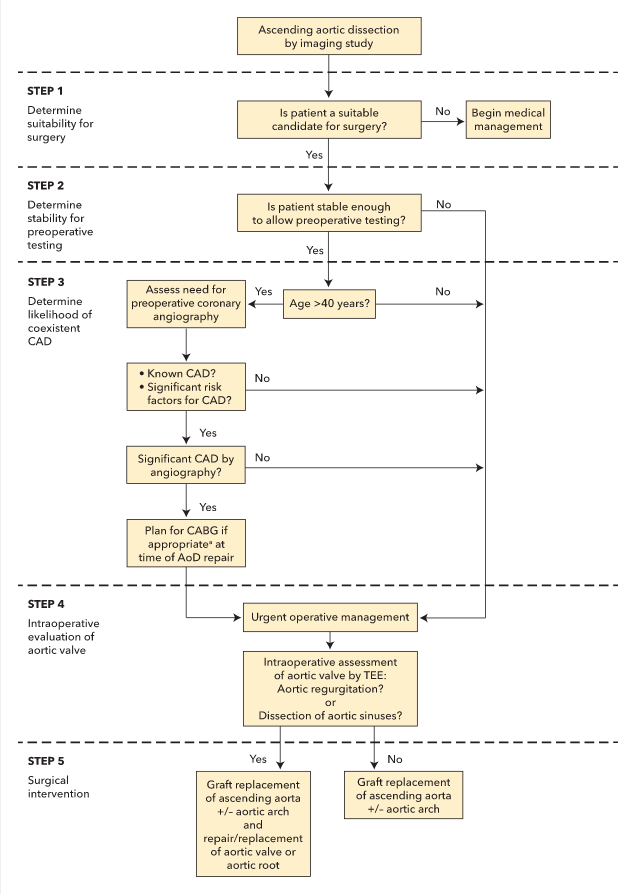

An algorithm for the management of acute ascending aortic dissections is shown in Figure 43. Referral for emergency surgery should be considered in all patients with acute aortic dissection and cardiogenic shock, patients with type A aortic dissection, and patients with type A intramural hematoma, given the very high mortality rate associated with these conditions. Decisions regarding concomitant aortic arch reconstruction, aortic valve replacement, branch vessel repair, and/or coronary artery bypass graft surgery or coronary artery reimplantation depend on the anatomy of the aortic dissection, involvement of the aortic valve or branch vessels, and various other patient characteristics.

Patients who present with uncomplicated type B aortic syndromes may be treated with medical therapy initially. TEVAR, when compared with medical therapy, is associated with similar clinical outcomes and improved survival and disease progression measures at 2 years. Patients with type B aortic dissection and refractory chest/back pain or hypertension, rapid aortic expansion, or organ malperfusion should undergo aortic repair.

In patients with an intramural aortic hematoma or penetrating aortic ulcer, treatment choices depend on the location of the hematoma or ulcer, progression to aortic dissection, and evidence of aortic enlargement. Immediate aortic repair is indicated in patients with an ascending aortic intramural hematoma or penetrating aortic ulcer and in those with enlargement or progression of disease after detection.

Role of Genetic Testing and Family Screening

Genetic conditions that predispose patients to thoracic aortic aneurysm syndromes include Marfan, Ehlers-Danlos, and Loeys-Dietz syndromes (see Table 33). Clinical findings and a family history of connective tissue disease often lead to genetic testing, for either diagnostic confirmation or screening of family members. Noninvasive imaging of the aorta should be performed if a pathogenic genetic mutation is found, and routine surveillance (initially at 6 months and then annually, if findings are stable) should follow to ensure that the aorta is not rapidly enlarging.

In first-degree relatives of patients with TAA and/or dissection, noninvasive imaging of the aorta should be performed to identify those with asymptomatic disease. In first-degree relatives of patients with a mutant gene (FBN1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2, COL3A1, MYH11) and aortic aneurysm and/or dissection, genetic counseling and testing should be performed. Relatives with the genetic mutation should then undergo noninvasive imaging of the aorta.