Cutaneous Manifestations of Internal Disease

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Rheumatology

Dermatomyositis

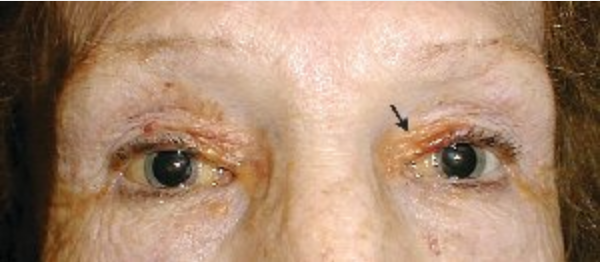

Dermatomyositis is an autoimmune disease that affects skin and proximal muscles in varying degrees of combination. Heliotrope rash (with pink-violet macules to edematous plaques on the eyelids) and Gottron papules (with lichenoid pink-violet papules on the knuckles, elbows, or knees) are pathognomonic signs of dermatomyositis. Patients commonly exhibit pink scaly plaques or macules on the scalp that extend onto the superior forehead, with varying degrees of nonscarring hair loss. The “shawl sign” refers to the pink-violet or poikilodermatous photodistributed macules with spotty hyper- and hypopigmentation (“salt and pepper”) with telangiectasia and atrophy on the upper back, whereas the anterior V-sign references similar findings on the upper chest in a V shape (Figure 105). The Gottron sign manifests as pink macules over the knuckles, elbows, or knees without papules (Figure 106). The nailfold capillary beds of patients with dermatomyositis often demonstrate alternating areas of dilatation and dropout with periungual erythema. Cuticular overgrowth and hemorrhagic infarcts are also characteristic.

The shawl sign demonstrating a photodistributed erythematous patchy rash on the upper back in a patient with dermatomyositis.

The shawl sign demonstrating a photodistributed erythematous patchy rash on the upper back in a patient with dermatomyositis.

Gottron papules are violaceous, slightly scaly plaques over the bony prominences on the hands.

Gottron papules are violaceous, slightly scaly plaques over the bony prominences on the hands.

Dermatomyositis and cutaneous lupus erythematosus can appear clinically similar. These conditions can be distinguished by sparing of the knuckles and upper eyelids in cutaneous lupus erythematosus, whereas dermatomyositis favors these areas. Dermatomyositis and CLE are essentially indistinguishable on skin biopsy.

Amyopathic dermatomyositis refers to characteristic skin findings without clinical or laboratory evidence of muscle disease for 6 months without treatment. This variant of dermatomyositis is about as common as classical disease. Amyopathic dermatomyositis is important to recognize because it carries similar risks for malignancy and interstitial lung disease (see MKSAP 18 Rheumatology).

The antisynthetase syndrome is a constellation of findings including dermatomyositis, hyperkeratotic, fissured skin on the palmar and lateral aspects of fingers (mechanic's hands), fevers, Raynaud phenomenon, elevated titers of anti-synthetase antibodies, and often interstitial lung disease. Anti-Jo1 is the prototypical antisynthetase antibody (Figure 107).

The cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis typically improve with the treatment of the associated myositis. It is a photosensitive disease, so aggressive photoprotection is foundational. Topical glucocorticoids are recommended as initial therapy but are often inadequate to control the skin lesions. Antimalarial agents can be helpful but can also flare the disease or cause drug-induced myopathy. Methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine can be helpful. There are several reports supporting the use of JAK/STAT inhibitors in resistant cases. Intravenous immunoglobulin is a valuable tool in cases of severe recalcitrant skin disease.

Sclerosing Disorders

The scleroderma family of disorders is discussed in the MKSAP 18 Rheumatology section. Patients with sclerosing disorders may exhibit skin findings that include “puffy hands” (early diffuse systemic sclerosis) and skin tightening (advanced diffuse systemic sclerosis) (Table 22). Raynaud phenomenon, especially with periungual capillary changes, is very common in systemic sclerosis and usually precedes skin disease (Figure 108).

Treatment with disease-modifying anti-inflammatory drugs such as methotrexate and mycophenolate are recommended to slow the progression of cutaneous sclerosis but result in only modest benefit. Patients with progressive sclerosis will progress to sclerodactyly or thick, hide-like skin of the fingers. This skin sclerosis will progress from distal to proximal (Figure 109). Both diffuse and limited sclerosis can affect the face resulting in restriction of the oral aperture, atrophied lips, and perioral creases radiating around the mouth (Figure 110). Sclerosis can result in acroosteolysis (resorption of the finger tips) and fixed contractures of the fingers, wrists, elbows, or feet.

Localized scleroderma (morphea) begins as red-violet plaques that progress to isolated sclerotic circumscribed plaques (Figure 111). The scarring sclerosis is permanent, and active lesions will have a violet-pink border that fades as disease activity burns out. Most commonly, patients will have one to a few plaques, but the disease can generalize. Morphea is not associated with sclerodactyly or systemic disease (esophageal dysmotility, interstitial lung disease, or kidney involvement). Raynaud phenomenon is uncommon in these patients. Treatment is best accomplished with topical and systemic glucocorticoids or calcineurin inhibitors, methotrexate, or UVA therapy.

Plaque morphea with red-violet inflammation at the border that indicates continued inflammatory activity.

Plaque morphea with red-violet inflammation at the border that indicates continued inflammatory activity.

Eosinophilic fasciitis is sclerosis of the deep dermis and subcutis. Patients report tightening of the skin, mostly on the arms, and the appearance of the “dry river bed sign.” This sign alludes to the collapsed appearance veins in the arms. The condition has been described to appear after periods of intense physical activity. Treatment includes systemic glucocorticoids or methotrexate.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis may feature several cutaneous features, most notably rheumatoid nodules and rheumatoid vasculitis.

Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis and are recognized as firm, nontender, dermal-to-subcutaneous nodules that can be moveable or bound to underlying fascia or bone. They vary in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and appear most commonly over pressure points and on the extensor surfaces of joints or tendons (Figure 112); however, they have been described almost everywhere on and in the body, including lungs, lymph nodes, and other organs. About one third of rheumatoid arthritis patients develop rheumatoid nodules. During treatment with methotrexate, the nodules may rapidly proliferate (accelerated nodulosis).

Rheumatoid nodules appear as slowly developing, firm, painless, subcutaneous nodules located at pressure points or over the extensor surfaces of joints and tendons.

Rheumatoid nodules appear as slowly developing, firm, painless, subcutaneous nodules located at pressure points or over the extensor surfaces of joints and tendons.

Rheumatoid vasculitis is much less common and typically occurs in elderly male smokers with long-standing disease and high titers of rheumatoid factor. It can appear as a small or medium-sized vasculitis, with pigmented purpura, nodules, or stellate purpura and ulcers, and may affect nerves or organs.

Rheumatoid vasculitis commonly affects small to medium-sized vessels of the skin, digits, peripheral nerves, eyes, and heart. Small-vessel vasculitis (leukocytoclastic vasculitis) appears as palpable purpura. In medium-vessel disease, nodules, ulcerations, livedo reticularis, and digital infarcts can occur. Periungual purpura (Bywaters lesions) is the result of nailfold thrombosis and appears as purpuric papules on the digital pulp of a few digits and in the nail fold area.

Vasculitis

Vasculitis is discussed in detail in MKSAP 18 Rheumatology. This section focuses only on the cutaneous findings of vasculitis.

Small-vessel vasculitis affects the capillaries and venules. Patients develop palpable purpura, and/or petechiae, which are nonblanching hemorrhages, on dependent areas such as the shins, feet, hips, and buttocks, as well as pressure areas such as under the elastic band of clothing (Figure 113). Lesions may coalesce to form purpuric plaques or ulcerate.

Small-vessel vasculitis is a finding, not a diagnosis, and determining the cause is critical. Idiopathic small-vessel vasculitis involving only the skin is common, but the findings of small-vessel vasculitis can be seen in many systemic diseases such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, drug reactions, and infective endocarditis. Skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence is important, as cases with IgA deposition (rather than IgG or IgM) are more likely to have systemic effects. An urticarial variant will deplete complement levels and is highly associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Complement levels, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, cryoglobulin, and hepatitis testing can be helpful to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Treatment of idiopathic cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis includes elevation, compression, NSAIDs, and antihistamines. Complicated or chronic cases may require glucocorticoids, dapsone, colchicine, or immunosuppressants.

Medium-vessel vasculitis affects the arterioles, including those that travel through the subcutis to supply segments of the skin. Inflammation and destruction of the vessels results in tender nodules on the legs and livedo reticularis and may be associated with reticulate purpura (Figure 114) or stellate ulceration (see Dermatologic Emergencies). Severe cases can cause ischemia or infarction of the digits, nose, ears, or genitals. Examples of conditions that can cause medium-vessel vasculitis skin findings include polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatous polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatous polyangiitis, drug-induced vasculitis (particularly from cocaine cut with levamisole), and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. Consider testing for hepatitis B and C in patients with medium-vessel vasculitis. There is a cutaneous-only variant of polyarteritis nodosa, which is treated in a similar fashion to idiopathic cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis.

Livedo reticularis on the feet, recognized as a red-blue, reticulated vascular network in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Livedo reticularis on the feet, recognized as a red-blue, reticulated vascular network in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Large-vessel vasculitis does not typically involve skin findings, except for a palpable temporal cord in giant cell arteritis or in severe cases of Takayasu arteritis where ischemia or necrosis may occur.

Cryoglobulinemia is a condition characterized by soluble antibodies that precipitate from serum when cooled below body temperature. The disease may manifest as a combination of small- and medium-vessel vasculitis (cryoglobulinemic vasculitis) and may exhibit symptoms from both or either category. Palpable purpura, subcutaneous nodules, reticulate purpura, or stellate ulceration may occur starting on the lower legs. Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis is usually secondary to another condition. Treatment is best directed at the underlying disease, but systemic glucocorticoids or rituximab can be helpful, particularly in cases associated with viral hepatitis.

Nephrology

Persons with end-stage kidney disease often have cutaneous findings. These findings have an insidious onset and can be quite subtle in the early stages. Xerosis and pruritus are most frequently seen. Pruritus may lead to chronic excoriations, lichenification, and prurigo-like changes. The exact mechanism of how end-stage kidney disease causes pruritus is still unknown. It is likely caused by diminished excretion of metabolites.

Dialysis is helpful in some patients, but not all. The itching can be treated with oatmeal baths, the liberal use of emollients, and over-the-counter antipruritics. Traditional soaps should be avoided and replaced with synthetic detergent cleansers (Dove, Cetaphil, and Olay). Topical glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and phototherapy have also been found to be helpful. There are three unique skin disease states seen predominately in persons with end-stage kidney disease: calciphylaxis, Kyrle disease, and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare disease seen most commonly in persons with chronic end-stage kidney disease, and those on dialysis with an elevated calcium-phosphorous product greater than 70 mg2/dL2. Parathyroid hormone levels are often dramatically elevated. Although the precise mechanism is not fully elucidated, those with end-stage kidney disease exhibit abnormalities in the endothelial cells, which allow for an abnormal deposition of calcium within the lumen of the dermal arterial and capillary vasculature. As the calcium deposition increases, small thromboses form that lead to ischemia and infarctions of the overlying tissue (Figure 115). The tissue becomes necrotic, painful, and a potential source for secondary infection that may lead to sepsis and death. Patients with calciphylaxis have a greater than 80% 1-year mortality rate. Body areas with high adipose tissue content are preferentially affected. The thighs and abdominal pannus are two of the most frequent areas involved.

Calciphylaxis showing eschar with angulated border on a patient's thigh. Note the central necrosis with surrounding erythema.

Calciphylaxis showing eschar with angulated border on a patient's thigh. Note the central necrosis with surrounding erythema.

The initial presentation may start as tender dusky red macules or a livedo reticularis pattern. It quickly progresses to develop tender subcutaneous plaques with an overlying dusky red discoloration. Surrounding purpura is often found. The area of involvement quickly expands in an angulated arrangement. As the skin infarcts, a black eschar forms. Because of poor underlying blood flow, the sores do not heal, which leads to chronic open ulcers and eschars that are highly susceptible to infections.

In those patients with hyperparathyroidism, parathyroidectomy may be helpful. Surgical debridement of dead tissue and prompt treatment of infection is important. Using a low-calcium dialysate during dialysis may help reduce the calcium-phosphorous product and slow down the deposition of calcium in the small vessels. The use of intravenous sodium thiosulfate has been reported to be beneficial because it works by increasing the solubility of the calcium deposits, thus clearing the blockages. Bisphosphonates may be beneficial in patients who have failed other forms of therapy.

Kyrle Disease

Kyrle disease, a type of perforating dermatosis, is seen in patients with end-stage kidney disease and diabetes mellitus. Patients develop pruritic hyperkeratotic umbilicated papules or nodules with overlying hyperpigmentation. Within the umbilicated region is a firm central keratin plug or core (Figure 116). This plug contains collagen bundles that are being extruded through the epidermis. Treatment is directed at the pruritus with the use of oatmeal baths, synthetic detergent cleansers, and liberal use of emollients and topical antipruritic agents. If only a few nodules are present, surgical removal is a treatment consideration.

Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis occurs in patients with end-stage kidney disease who have been exposed to gadolinium-containing contrast agents. Patients present with symmetrical, fibrotic indurated papules, plaques, or subcutaneous nodules most commonly located on the legs, the mid-thighs, and upper arms (Figure 117). The skin findings can occur weeks to years after exposure to gadolinium-containing contrast dyes. There are many anecdotal treatments including ultraviolet A phototherapy, extracorporeal photopheresis, kidney transplantation, and cyclophosphamide. Because of screening protocols that have been put in place before patients are given gadolinium-based contrasts, there has been a marked reduction in the number of new cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

Gastroenterology

Inflammatory bowel disease has been found to have an association with the development of erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum. Although these skin conditions can be idiopathic, their presence should alert the clinician to look for an underlying inflammatory bowel disease.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is associated with celiac disease. Porphyria cutanea tarda is seen most frequently in association with alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis C infection, or hemochromatosis.

Patients with cirrhosis will often develop nonspecific skin findings such as palmar erythema, spider telangiectasia, xerosis, and pruritus. Terry nails, manifested by whitening of the nail bed caused by edema, are seen in end-stage liver disease (see Nail Disorders).

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Approximately half the cases of pyoderma gangrenosum are associated with an underlying disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease, leukemia, or lymphoma. Pyoderma gangrenosum presents with an exquisitely tender papule, pustule, or nodule. The area quickly enlarges and begins to ulcerate in a cribriform pattern, with intervening strands of epithelium. There is a characteristic violaceous border with an overhanging epithelium (Figure 118) around the central exudative ulcer, which is often described as a “wet ulcer.” The most frequent location is the lower leg. Pyoderma gangrenosum is also seen frequently in association with a stoma site (peristomal) after ostomy placement in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. Pyoderma gangrenosum often occurs in the site of trauma (pathergy), and there are numerous reports of pyoderma becoming much worse after surgical debridement. Once the inflammation has been treated and the ulcer heals, patients are often left with a prominent atrophic scar.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a diagnosis of exclusion and is made after ruling out other causes of ulcerations. For this reason, diagnosis can be challenging and delayed. Skin biopsies are nonspecific but will often show a neutrophilic-rich ulceration with marked tissue edema. Tissue cultures should be negative, but are frequently complicated by surface colonization.

Management of pyoderma gangrenosum is multidimensional. The underlying disease state must be evaluated and treated. Initial therapy directed at the ulcer is with glucocorticoids, and small areas can be treated with intralesional glucocorticoids or potent topical glucocorticoids; however, most patients will require systemic glucocorticoid treatment. Many treatment options are available and include cyclosporine, infliximab, dapsone, colchicine, mycophenolate mofetil, intravenous immunoglobulin, methotrexate, and thalidomide. Trauma and surgical debridement should be avoided to prevent pathergy. Local wound care is often best achieved with a wound care specialist to ensure proper care to avoid secondary infection and to minimize other complications. Recognition and treatment of secondary infection are difficult and require vigilance and frequent evaluations.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a neutrophilic dermatoses caused by IgA antibodies against tissue and epidermal transglutaminase. Dermatitis herpetiformis typically presents with intensely pruritic papules and fragile vesicles that rapidly break leaving tiny erosions (see Autoimmune Bullous Diseases and MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology and Hepatology). The elbows, knees, scalp, and lower back are the most common sites of involvement. A skin biopsy will show numerous neutrophils stuffing the dermal papillae, and a granular pattern of IgA deposition will be seen on direct immunofluorescence.

Most patients with dermatitis herpetiformis will have an underlying gluten-sensitive enteropathy; however, they are usually free of gastrointestinal symptoms. Interestingly, only 20% of patients with celiac disease will go on to develop dermatitis herpetiformis; however, all patients with dermatitis herpetiformis should be evaluated for underlying bowel involvement. Treatment is usually initiated with dapsone and a gluten-free diet. Dapsone is quickly effective in inducing a clinical remission, but a gluten-free diet is the preferred long-term management of both the skin and bowel disease.

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda presents with increased skin fragility noted on sun-exposed areas, most frequently on the dorsal hands. Small vesicles rupture leaving erosions (Figure 119). On close examination, milia are often seen in the healed areas that were once vesicles. Milia represent small epidermal inclusion cysts that develop after subepidermal blister formation. As the disease progresses, hyperpigmentation of skin and hypertrichosis of the forehead/temples is commonly seen. Jaundice may be present.

Porphyria cutanea tarda manifests as a chronic blistering disease with epidermal erosions on sun-exposed skin, especially on the backs of the hands.

Porphyria cutanea tarda manifests as a chronic blistering disease with epidermal erosions on sun-exposed skin, especially on the backs of the hands.

Porphyria cutanea tarda is most commonly caused by an acquired defect of hepatic uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UPDC) enzyme. Reduced UPDC activity results in the accumulation of porphyrinogens that are oxidized to porphyrin. Accumulated porphyrins are photosensitizing and when they are transported to the skin cause phototoxicity on light exposure. Chronic hepatitis C infection is the most likely cause, followed by alcohol-induced liver damage and hemochromatosis. A urine sample examined under Wood lamp illumination will fluoresce. The diagnosis can be confirmed by increased plasma or urine porphyrin level analysis.

The treatment is aimed at decreasing iron overload. In addition to treating the underlying condition, phlebotomy is the mainstay of therapy. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine is an effective second option for those who do not have significant iron overload. It is dosed at 200 mg once or twice weekly.

Hematology/Oncology

Cutaneous manifestations of malignancy include both malignancy-related cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes and skin disorders (Table 23) and hereditary syndromes with an associated risk of malignancy with cutaneous findings as part of the syndrome (Table 24).

Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, a dense dermal infiltrate on histology, and characteristic skin lesions. Skin lesions are painful, edematous, red-to-violaceous “juicy” papules and plaques, most common on the face, neck, and extremities (Figure 120). Additional diagnostic criteria include responsiveness to oral glucocorticoids and absence of infection. Most cases of Sweet syndrome typically develop after an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection or in the setting of hematologic abnormalities, particularly myelodysplastic syndrome and myelodysplastic syndrome evolving into acute myeloid leukemia (Table 25). Sweet syndrome has also been associated with solid malignancies and medications (particularly neutrophil-stimulating medications such as granulocyte-colony stimulating factor and all-trans retinoic acid. In addition to the skin eruption, patients typically have high fevers, leukocytosis with a left shift, elevated inflammatory markers, and often muscle or joint pain.

Amyloidosis

The hallmark of systemic amyloidosis with cutaneous involvement and cutaneous amyloidosis is extracellular deposition of altered amyloid protein in the skin. In primary (systemic) immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis (AL), AL amyloid deposits in multiple organs including the skin. Skin manifestations are present in 30% to 40% of patients and include generalized waxy appearance, easy bruising with minor pressure (pinch purpura) (Figure 121), violaceous discoloration around the eyes (“raccoon eyes”), yellow waxy papules and plaques especially in a periorbital location (Figure 122), dystrophic nails, and macroglossia (Figure 123). When the diagnosis is suspected, patients should be screened with immunofixation of serum and urine and serum free light chain assay. Skin biopsies for the diagnosis of AL are controversial, as even when amyloid protein is seen in the dermis, the biochemical composition must be established with immunofixation studies (see MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology).

A 50-year-old man with prominent periorbital purpura. Easy bleeding leads to characteristic “pinch purpura” (arrow).

A 50-year-old man with prominent periorbital purpura. Easy bleeding leads to characteristic “pinch purpura” (arrow).

Massive infiltration by amyloid leading to macroglossia. Note the indentations from teeth pressing on the firm and enlarged tongue (arrow).

Massive infiltration by amyloid leading to macroglossia. Note the indentations from teeth pressing on the firm and enlarged tongue (arrow).

Extensive purpura in a 66-year-old man with amyloidosis. Only minor pressure will cause dermal bruising (“pinch purpura”). The ecchymoses labeled V3-V6 are from suction cup ECG chest leads used the day before this photo was taken.

Extensive purpura in a 66-year-old man with amyloidosis. Only minor pressure will cause dermal bruising (“pinch purpura”). The ecchymoses labeled V3-V6 are from suction cup ECG chest leads used the day before this photo was taken.

Endocrinology

Many patients with endocrine disorders have associated dermatologic conditions. This section will focus on some conditions associated with thyroid disease and diabetes mellitus, since a high proportion of these patients have at least one dermatologic complication.

Eruptive Xanthomas

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits whose presence is suggested by characteristic cutaneous papules, plaques, or nodules.

Cutaneous xanthomas can be idiopathic and not associated with an underlying disorder or an indication of a primary dyslipidemia, hyperlipidemia secondary to another disorder, medication effect (estrogens, prednisone, protease inhibitors), or hematologic disease.

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a rapid onset of numerous yellow papules with surrounding erythema primarily on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and buttocks. Diagnosis is made by a skin biopsy that shows lipid-laden macrophages in the dermis. Eruptive xanthomas are pathognomonic of hypertriglyceridemia with a vast number of these patients also having a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Lesions typically resolve with control of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.

Acanthosis Nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans presents as velvety-to-verrucous, gray-to-brown thickening with accentuation of skin marking and is seen in the intertriginous folds and neck (Figure 124). Histologically, the pigment change results from epidermal thickening. Acanthosis nigricans is more common in persons of color. It can be associated with diabetes or a malignant and paraneoplastic syndrome. Therefore, a diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans should prompt screening for diabetes and, if of acute onset, screening for malignancy. It is mainly of cosmetic concern and resolves when the underlying condition is treated. Topical salicylic acid, retinoids, and ammonium lactate have modest benefit.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a chronic condition that is seen mainly in patients with diabetes mellitus, both type 1 (more commonly) and type 2. Necrobiosis lipoidica presents as well-demarcated, indurated, yellow-brown oval plaques with central atrophy and telangiectasias. Lesions are typically seen on the bilateral pretibial areas but can occur anywhere on the body.

The diagnosis is usually made on clinical findings, but a punch biopsy of skin to include subcutaneous tissue can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology shows a necrobiotic granulomatous dermatitis. Only a small portion of patients with diabetes (0.3% to 1.6%) develop necrobiosis lipoidica, and in most patients the diabetes precedes necrobiosis lipoidica. Patients with necrobiosis lipoidica without diabetes should be monitored closely for diabetes. Glycemic control does not usually lead to resolution of necrobiosis lipoidica. Treatment is challenging, and relapses are common.

Pretibial Myxedema

Autoimmune thyroid disease, particularly Graves disease, may uncommonly be associated with pretibial myxedema, an accumulation of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis, usually over the lower legs. Pretibial myxedema presents with firm nodules and plaques with a “peau d’ orange” appearance on the pretibial area (Figure 125). Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, elevated thyroid-stimulating immunoglobins, and skin biopsy showing characteristic accumulation of mucin in the dermis. Control of the hyperthyroidism does not usually lead to resolution of pretibial myxedema.

Infectious Disease

Dermatologic conditions are very common in patients with HIV and AIDS, and in some this may be the first clue of infection. Cutaneous manifestations can be divided into three categories: immunologic (decreasing CD4 count), related to antiretroviral therapy, and increased prevalence or severity of endemic infections. Many of these conditions are also found in the general population; however, in patients with HIV, they tend to have increased severity, prevalence, atypical presentations, and be recalcitrant to treatment. Because of atypical presentations and the increased risk of infections, if the diagnosis cannot be made on clinical grounds, two skin biopsies should be performed: one for histologic evaluation and the second for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal culture.

Acute seroconversion syndrome (primary HIV infection) is an acute mononucleosis-like illness that occurs in many (90%) but not all patients 2 to 4 weeks after infection. Clinical presentation includes fever, sore throat, cervical adenopathy, and an exanthem. The exanthem is made up of asymptomatic erythematous macules and papules involving the face and trunk. The recommended algorithm for diagnosing HIV infection involves use of the fourth-generation HIV test. This test combines an immunoassay for HIV antibody with a test for HIV p24 antigen.

Many HIV-associated primary dermatologic disorders, including xerosis, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and psoriasis, are related to the T-cell imbalances. Atopic dermatitis and xerosis are related and present with dry skin and eczematous patches. Both conditions are associated with pruritus, which is often severe and can be recalcitrant resulting in a high burden of morbidity for these patients. In seborrheic dermatitis, there are erythematous patches with greasy scale on the scalp, nasal labial folds, and chest. This condition is extremely common in patients with HIV, and most patients with AIDS have some compatible findings. The prevalence of psoriasis, which presents with plaques with overlying scale, and psoriatic arthritis, is increased in patients with AIDS but not those with HIV. New-onset pruritus, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and psoriasis that is severe and recalcitrant to treatment should prompt testing for HIV/AIDS.

Seborrheic dermatitits

Seborrheic dermatitits

Eosinophilic folliculitis is a condition that is almost exclusively seen in AIDS, in particular in later stages. It presents as extremely pruritic, erythematous follicular-based papules and pustules on the upper trunk, neck, and face. Skin biopsy is diagnostic, showing numerous eosinophils within the follicular infundibulum with destruction of the sebaceous gland. Treatment is challenging with first-line therapy being medium- to high-potency topical glucocorticoids.

Pulmonary

Lupus Pernio

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory granulomatous disease commonly associated with skin manifestations, some of which predict specific internal organ involvement. Lupus pernio is sarcoidosis of the nose and central face, manifesting as violaceous subcutaneous plaques or nodules, often with some overlying scaling. Lupus pernio is more common in skin of color and is associated with an increased risk for extracutaneous disease, particularly intrathoracic sarcoidosis. Sarcoid lesions may also preferentially develop in sites of trauma, and these lesions are also associated with an increased risk of pulmonary disease. Other more common cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis include violaceous papules on the nose, periorbitally and around the oropharynx, and nasal openings.

The term “lupus pernio” is a source of potential confusion. “Lupus” generally refers to systemic lupus erythematosus; “pernio” generally refers to a condition of purple papules on the distal digits exacerbated by cold and moisture; and lupus vulgaris is a form of tuberculosis of the skin. Lupus pernio has little to do with these, however.

Limited cutaneous sarcoidosis is treated with topical or intralesional glucocorticoids and more extensive disease is typically treated with hydroxychloroquine. Patients who fail to respond may be treated with thalidomide, methotrexate, or occasionally TNF-α inhibitors.

Others

Erythema nodosum is the most common form of panniculitis, or inflammation of the fat. Erythema nodosum manifests as ill-defined, tender, bilateral dermal red or violaceous nodules, most commonly on the bilateral shins (Figure 126). Most resolve spontaneously over 4 to 6 weeks. Erythema nodosum is a nonspecific reaction to some systemic process.

Erythema nodosum manifests as painful, red-brown nodules on the anterior shins.

Erythema nodosum manifests as painful, red-brown nodules on the anterior shins.

The most common associations are streptococcal infection, hormones (including oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, or pregnancy), inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, and other medication reactions. The appearance of erythema nodosum in patients with sarcoidosis usually signifies an acute presentation with a good long-term prognosis. The combination of erythema nodosum, arthritis, hilar lymphadenopathy, and fevers constitute Löfgren syndrome. This set of findings is so specific for sarcoidosis that a biopsy is not needed to confirm the diagnosis. Most cases of erythema nodosum resolve spontaneously, and therapy is supportive in nature with NSAIDs and compression stockings.

The diagnosis of EN can be clinically based on the acute onset of tender nodules on the bilateral shins typically in a young woman. Biopsy is not necessary in typical lesions.

Most authorities recommend a chest radiograph in the evaluation of EN to assess for the presence of lymphoma, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and fungal infection such as coccidioidomycosis.

In the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms, a colonoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease is unlikely to reveal a causative diagnosis. Patients with disseminated gonococcal infection and bacteremia manifest vesiculopustular or hemorrhagic macular skin lesions, not tender subcutaneous nodules as seen in this patient.