Crystal Arthropathies

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Gout

Epidemiology

Gout is characterized by intermittent painful inflammatory joint attacks, in response to crystals formed as a consequence of excessive levels of uric acid (hyperuricemia). Gout is increasingly common, with a U.S. prevalence of approximately 4%. Factors contributing to this increase include dietary changes, increasing obesity, and an aging population (the elderly account for the sharpest rise in gout over the past few decades). Nearly all patients with gout have comorbidities, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Comorbidities frequently complicate treatment by posing relative contraindications for appropriate therapeutics (for example, CKD for NSAIDs or colchicine).

Men reach a steady-state serum urate level after puberty, whereas premenopausal women are generally protected from hyperuricemia by estrogenic effects. It is rare for premenopausal women to develop gout, whereas men usually have their first gout attack in the third to fifth decade.

Pathophysiology

Uric acid is the end product of purine metabolism, and about two thirds of urate production derives from cellular turnover of nucleic acids (purine bases); the remainder is derived from dietary purine intake. A small proportion of patients overproduce urate on an inherited metabolic basis. Unlike most mammals, humans do not express uricase, an enzyme that converts urate into highly soluble allantoin. Urate therefore accumulates and can precipitate as crystals in joints and other tissues if serum concentrations exceed the saturation point. At normal body temperature, the saturation point of urate is 6.8 mg/dL (0.40 mmol/L). At lower temperatures (for example, in the extremities), the saturation point is lower.

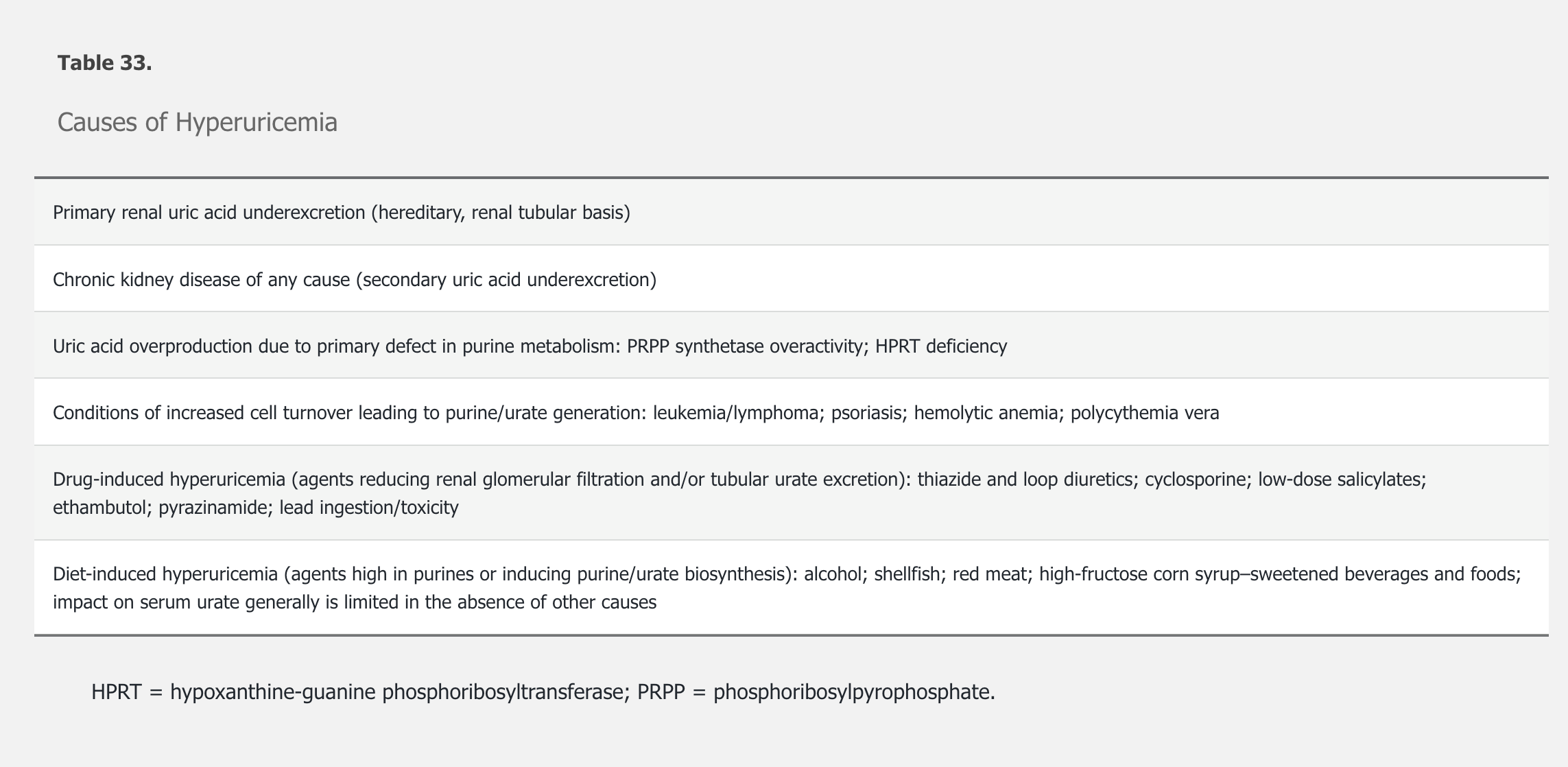

Nearly all urate is filtered at the glomerulus, but approximately 90% is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule; in most patients with gout, hereditary underexcretion of uric acid contributes to hyperuricemia (Table 33). Not all patients with hyperuricemia develop gout; about 20% of the U.S. population is hyperuricemic compared with the 4% prevalence of gout. The factors that lead to the development of gout in hyperuricemia are unclear, but degree of elevation in urate level is predictive. A serum urate level greater than 10 mg/dL (0.59 mmol/L) is associated with a 30% likelihood of an initial attack of gout within 5 years.

Acute gouty arthritis is triggered when tissue macrophages ingest uric acid crystals, leading to the generation of interleukin (IL)-1β. IL-1β is an inflammatory cytokine that causes local vasodilation, triggers production of other inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor α and IL-6), and both recruits and activates neutrophils. Complement activation on the surface of uric acid crystals also promotes neutrophil recruitment. Neutrophils are primarily responsible for the symptoms and signs of an acute gout attack.

Clinical Manifestations

Three requirements generally must be fulfilled for the onset of clinically apparent gout: 1) hyperuricemia, usually long-standing, 2) uric acid deposition in the joints and/or soft tissues, and 3) a reaction to phagocytosed crystals that leads to an acute inflammatory event.

Acute Gouty Arthritis

Initial acute gouty attacks are typically monoarticular, and ≥50% of first attacks in men involve the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint of the great toe (podagra). Inflammatory states such as infection, surgery, and myocardial infarction can provoke gouty attacks, possibly through volume and pH changes. The hallmarks of an attack are pain, tenderness, swelling, redness, and warmth of the affected area. Attacks typically begin at night, and peak within 12 to 24 hours. The pain is often so exquisite that even the touch of a sheet on an affected toe is unbearable. Untreated, most gout attacks self-resolve within days to a few weeks, although with long-standing disease, attacks can persist for months. In men with established disease, attacks eventually affect joints other than the first MTPs, including the proximal feet, ankles, and knees, and later virtually any joint, including the spine. Postmenopausal women may present differently, with initial attacks often involving finger joints already affected by osteoarthritis. For those with more severe or long-standing disease, polyarticular attacks may occur. Soft tissues can also be involved, manifesting as acute bursitis, periarthritis, and gouty panniculitis and cellulitis, the last of which can be misdiagnosed as a refractory bacterial soft-tissue infection.

Intercritical Gout

Intercritical gout is the period between gout attacks. Early in the disease course, the intercritical period can be years, although most patients will have a second gout attack within 2 years. As the disease progresses, the intercritical period can progressively shorten. Even in the absence of acute arthritis, uric acid crystals still reside within joints and soft tissues, and low-grade inflammation persists in the absence of clinically apparent systemic disease.

Chronic Recurrent and Tophaceous Gout

Chronic recurrent gout and tophaceous gout result from a failure to recognize or adequately treat gout at an earlier stage.

In chronic recurrent gout, patients experience increasingly frequent and severe, and often polyarticular, arthritic attacks. These attacks may eventually evolve into a persistent chronic arthritis.

Other patients with long-standing disease develop tophaceous gout. Tophi are solid chalky white masses of uric acid, surrounded by inflammatory cells and a rind of fibrous tissue. They are located around joints and in soft tissues, with a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the elbows, the distal Achilles tendon, the fingers (usually from the proximal interphalangeal joints distally) (Figure 23), and the cartilaginous portions of the ears. The size ranges from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. Tophi are deforming, can interfere with function, and directly erode bone. Ulceration of overlying skin can occur, and accompanying infection can be difficult to treat because tophi are avascular.

Diagnosis

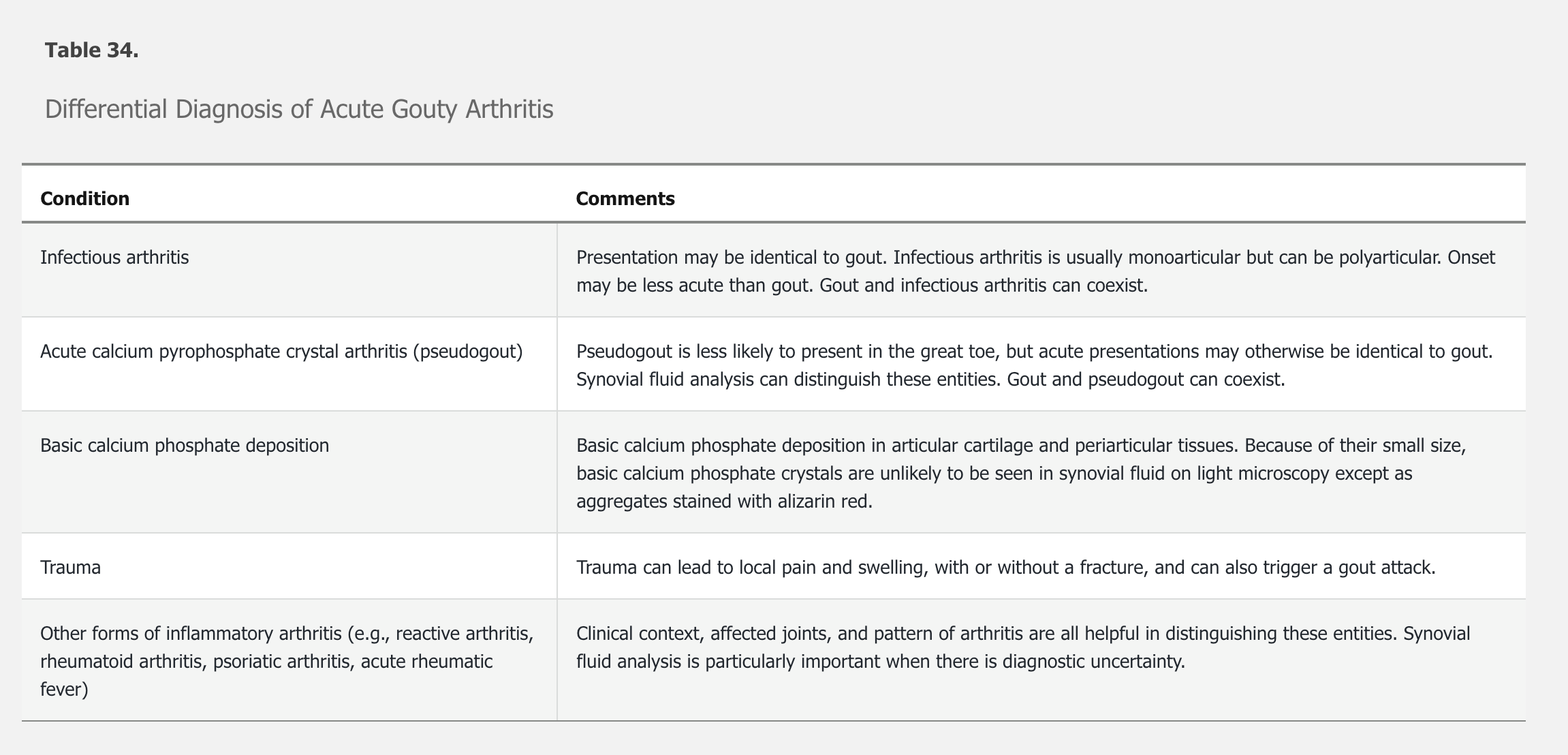

A diagnosis of acute gout should be entertained in any patient with an acute monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritis. The differential diagnosis is listed in Table 34. Although designed primarily for research, gout classification criteria are available for guidance, including as an online calculator (http://goutclassificationcalculator.auckland.ac.nz).

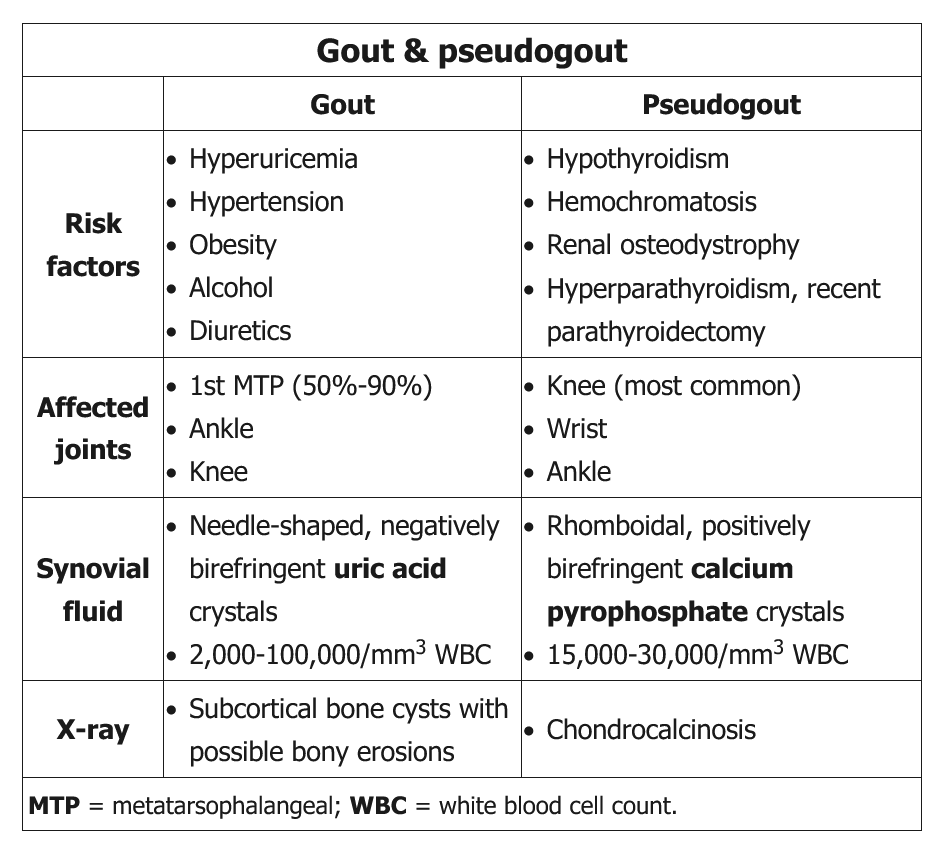

In every person suspected of having gout, a search for crystals in synovial fluid is recommended. Moreover, when infection is a concern, joint aspiration for Gram stain and culture is mandatory. The gold standard for the diagnosis of acute gout is the identification of negatively birefringent, needle-like uric acid crystals within neutrophils in fluid obtained by arthrocentesis. Negatively birefringent means that under polarized light, the crystals appear yellow when parallel and blue when perpendicular to the polarizing axis.

In any acute arthritis in an adult, gout should be considered. Findings that support an acute gout diagnosis when arthrocentesis is not feasible include onset of symptoms over several hours, first MTP joint or midfoot/ankle involvement, previous similar acute arthritis episodes, and severe pain. Male sex and associated cardiovascular diseases are also supportive. The involved joint(s) are warm, red, swollen, and very tender. Low-grade fever may be present. Measuring serum urate at the time of attack is often done but may not be helpful, because levels may drop precipitously during periods of acute systemic inflammation (owing to the uricosuric effects of circulating cytokines). Nonetheless, an elevated serum urate level increases the likelihood of gout, but hyperuricemia alone does not establish the diagnosis of gout. Checking the serum urate 2 weeks after acute gout resolution gives a more accurate measure of baseline level. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are elevated but are nonspecific. Joint fluid will have an inflammatory leukocyte count (above 2000/µL [2.0 × 109/L] and occasionally >100,000/µL [100 × 109/L], with neutrophil predominance). Importantly, the diagnosis of acute gout, even when confirmed by the presence of intracellular crystals in synovial fluid, does not definitively rule out a concomitant infection.

Imaging is recommended when arthrocentesis is not possible and a clinical diagnosis of gout is uncertain. The characteristic radiographic changes of established disease (punched-out lesions with overhanging edges of cortical bone) may help confirm a history of previously unrecognized gout (Figure 24). Ultrasounds can show unsuspected tophi or a double contour sign at cartilage surfaces, which is highly specific for urate deposits in joints. The ultrasound double contour sign, the identification of monosodium urate crystal deposition by dual-energy CT, and gout-related joint damage on radiography are all included in the new gout classification criteria.

Management

There are three components to treating gout: 1) treating acute attacks, 2) prophylaxis to prevent future attacks, and 3) urate-lowering therapy. See Principles of Therapeutics for details on the medications described in this section.

Treatment of Acute Gouty Arthritis

Treatment of acute gout focuses on anti-inflammatory therapy; colchicine, NSAIDs, and glucocorticoids are all reasonable options. Treatment choice should be determined by potential drug interactions and patient comorbidities. The simplest is colchicine, 1.2 mg at the first symptoms of a gout attack, followed 1 hour later by a 0.6-mg dose. Colchicine is most effective when used early in attacks (<24 hours after onset) and is less useful when the attack is well established. High-dose NSAID therapy for 5 to 7 days is effective, as are glucocorticoids in any form—intra-articular injection, intramuscular depot injection (for example, depo-methylprednisolone, 40-80 mg), or an oral “burst” of prednisone (for example, 0.5 mg/kg/d, for 5 days).

Colchicine is effective for acute gouty arthritis, but is limited by frequent gastrointestinal side effects and is a second-line agent. Colchicine is less effective than corticosteroids. Chronic administration in CKD patients can lead to colchicine accumulation in the blood and cause significant neuromyopathy.

Most gout attacks respond to a week or less of therapy, although more severe attacks may require a longer course of treatment. For patients with severe and refractory attacks, or with contraindications to other treatments, off-label use of IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra or canakinumab) can be considered. Gouty cellulitis, if present, should be treated as any other acute gout attack.

Urate-Lowering Therapy

Guidelines conflict as to whether patients with gout should receive dietary counseling to reduce serum urate levels. If recommended, patients may limit intake of shellfish, oily fish, red meat, high-fructose foods, and alcohol. Overly strict diets that are unlikely to be complied with are not helpful, however. Weight loss (when appropriate) and increasing dairy intake may also lower serum urate levels. In patients with hypertension, agents other than diuretics should be used; losartan, for example, has mild uricosuric effects.

It is important to note that guidelines differ regarding the role of pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy in patients with gout. The 2016 American College of Physicians guideline (http://annals.org/aim/article/2578528/management-acute-recurrent-gout-clinical-practice-guideline-from-american-college) notes a lack of evidence supporting a specific target level for urate lowering; this guideline stresses discussing the risks and benefits of urate-lowering therapy with patients and suggests a “treat to avoid symptoms” approach without specifically considering the serum urate levels. The 2020 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline strongly recommends initiating urate-lowering therapy in patients with two or more flares annually, tophi, or radiographic damage; conditionally recommends starting therapy in patients who have experienced multiple but infrequent (<2/year) flares; and conditionally recommends urate-lowering therapy for patients experiencing their first flare in the setting of stage 3 or higher CKD, serum urate level greater than 9.0 mg/dL (0.53 mmol/L), or urolithiasis. The ACR recommends treating to a maximum urate of less than 6.0 mg/dL (0.35 mmol/L).

Contrary to prior practice, urate-lowering therapy can be initiated during an acute attack if adequate anti-inflammatory therapy is concurrently started; doing so may improve compliance in some patients.

Three classes of urate-lowering therapy are available: xanthine oxidase inhibitors (reduce urate production), uricosuric agents (decrease renal urate resorption), and pegloticase (a uricase).

Allopurinol is the recommended first-line therapy and is FDA approved for doses up to 800 mg/d. According to the ACR, allopurinol should be initiated at 100 mg/d and titrated in 100-mg increments as needed, and for those with stage 4 or 5 CKD, allopurinol should be initiated at 50 mg/d and titrated in 50-mg increments as needed. An uncommon but serious complication of allopurinol is a hypersensitive rash that may progress to DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome; the drug should therefore be discontinued in most (if not all) patients who develop a rash. Patients from groups at higher risk for DRESS (certain Asian populations including Thai, Han Chinese, and Korean, and Black patients) should be tested for HLA B5801 before treatment with allopurinol and be considered for an alternative therapy if the result is positive.

Febuxostat (Uloric) is equally or more efficacious than allopurinol. It is less likely to cause hypersensitivity reactions than allopurinol and does not require dose adjustment in mild to moderate CKD, but it is expensive. In February 2019, the FDA mandated a boxed warning for febuxostat regarding the increased risk for cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality with the drug. This boxed warning was based on a large postmarketing trial that compared the cardiovascular safety of allopurinol and febuxostat. The trial was not placebo-controlled, and it remains unclear whether allopurinol improved cardiovascular mortality or febuxostat increased risk. The FDA has also limited the approved use of febuxostat for patients who are unresponsive to or cannot tolerate allopurinol.

The uricosuric agent probenecid (Probalan) is infrequently used as monotherapy because it is less effective than xanthine oxidase inhibitors and should be avoided in patients with CKD or nephrolithiasis. Combination therapy with a xanthine oxidase inhibitor and probenecid (or the incidentally uricosuric agent losartan) may be more effective than a xanthine oxidase inhibitor alone. A more effective uricosuric agent, lesinurad, was discontinued by its manufacturer in 2019 for business reasons.

For patients with severe recurrent and/or tophaceous gout intolerant or resistant to standard therapies, pegloticase is an option. Infused every 2 weeks, pegloticase lowers serum urate to nearly zero, but 30% to 50% of patients develop antibodies to the drug within a month, rendering it ineffective and increasing the likelihood of infusion reactions. Other urate-lowering therapies should be discontinued with initiation of pegloticase because they can mask the development of antibodies that manifest as rising serum urate levels. Patients starting pegloticase should be placed on prophylaxis to prevent acute gout attacks; colchicine, prednisone, or NSAIDs are appropriate. Pegloticase should be discontinued in any patient for whom it ceases to work. Coadministration of pegloticase with an immunosuppressive, such as methotrexate, may reduce the risk for loss of efficacy and infusion reactions.

Prophylaxis

When initiating urate-lowering therapy, mobilization of uric acid crystals from the joints and soft tissues can provoke acute attacks. Accordingly, patients starting urate-lowering therapy should be placed on anti-inflammatory prophylaxis to prevent flares. The ACR strongly recommends continuing prophylaxis for 3 to 6 months, with ongoing evaluation and continued prophylaxis as needed if flares continue. Most patients tolerate colchicine, 0.6 mg (once or twice daily); for those who do not, low-dose NSAIDs or glucocorticoids are appropriate substitutes.

Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition

Deposition of calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystals in and on cartilaginous surfaces can provoke acute inflammatory arthritis that is clinically similar to acute gout. Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) is less well characterized than gout, but four subgroups are described: asymptomatic CPPD; acute CPP crystal arthritis; chronic CPP crystal inflammatory arthritis; and osteoarthritis with CPPD.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

CPPD primarily affects the elderly, and prior joint damage is a significant risk factor. The risk for cartilage calcification (chondrocalcinosis) doubles for every decade past 60 years, and nearly half of patients in their late 80s have CPPD. For younger patients with CPPD, consideration of contributory metabolic disease (hyperparathyroidism, hemochromatosis, hypophosphatasia, hypomagnesemia) is warranted.

Hyperparathyroidism can lead to chondrocalcinosis in the articular cartilage; parathyroidectomy can precipitate a pseudogout attack due to an abrupt drop in serum calcium levels, which triggers crystal shedding into the synovial fluid.

The pathophysiology of CPPD is incompletely understood. Pyrophosphate produced by chondrocytes likely precipitates with calcium to form CPP crystals, which then activate inflammatory pathways resulting in an acute arthritic attack. CPPD may also drive osteoarthritis by inducing proinflammatory activity in chondrocytes and synovial fibroblasts, resulting in cartilage damage. Epidemiologic evidence suggests that cartilage calcification might play a role in osteoarthritis of the knees and wrists, but not at the hip.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Asymptomatic Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition

Asymptomatic CPPD occurs with radiographic changes in the absence of clinical symptoms. Cartilage calcification appears as a linear opacity below the surface of articular cartilage (Figure 25). It most commonly occurs in the knees, wrists (triangular fibrocartilage), pelvis (pubis symphysis), and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, in descending order. Asymptomatic CPPD is common in the elderly and in osteoarthritic joints, and it may be a precursor of osteoarthritis with CPPD.

Cartilage calcification (chondrocalcinosis) of the knee. This radiograph shows linearly arranged calcific deposits in the articular cartilage (arrow).

Cartilage calcification (chondrocalcinosis) of the knee. This radiograph shows linearly arranged calcific deposits in the articular cartilage (arrow).

Acute Calcium Pyrophosphate Crystal Arthritis

Acute CPP crystal arthritis (pseudogout) typically presents as a monoarticular inflammatory arthritis, characterized by sudden onset of swelling, pain, loss of function, tenderness, and warmth of the affected joint, usually a knee or wrist. Similar to acute gout, attacks may be provoked by systemic insults such as major surgery or acute illness. Attacks are usually milder than those of gout, but if untreated can persist for months. Definitive diagnosis requires identification of CPP crystals (along with leukocytes) in synovial fluid; in contrast to uric acid crystals, the CPP crystals are rhomboid shaped and positively birefringent under polarized light. Radiographic evidence of cartilage calcification in elderly patients with acute monoarticular arthritis is suggestive but not diagnostic of acute CPP crystal arthritis.

Chronic Calcium Pyrophosphate Arthropathy

Chronic calcium pyrophosphate arthropathy may be present as two patterns: (1) chronic calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystal inflammatory arthritis and (2) osteoarthritis with calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD). Chronic CPP crystal inflammatory arthritis is a polyarthritis involving the wrists and MCP joints (“pseudo–rheumatoid arthritis”); it is rare and difficult to treat. Osteoarthritis with CPPD manifests as typical osteoarthritic findings involving joints not commonly associated with osteoarthritis (such as shoulders or MCP joints); radiographic CPPD often precedes the onset of osteoarthritis, suggesting a causal role for the CPP.

Management

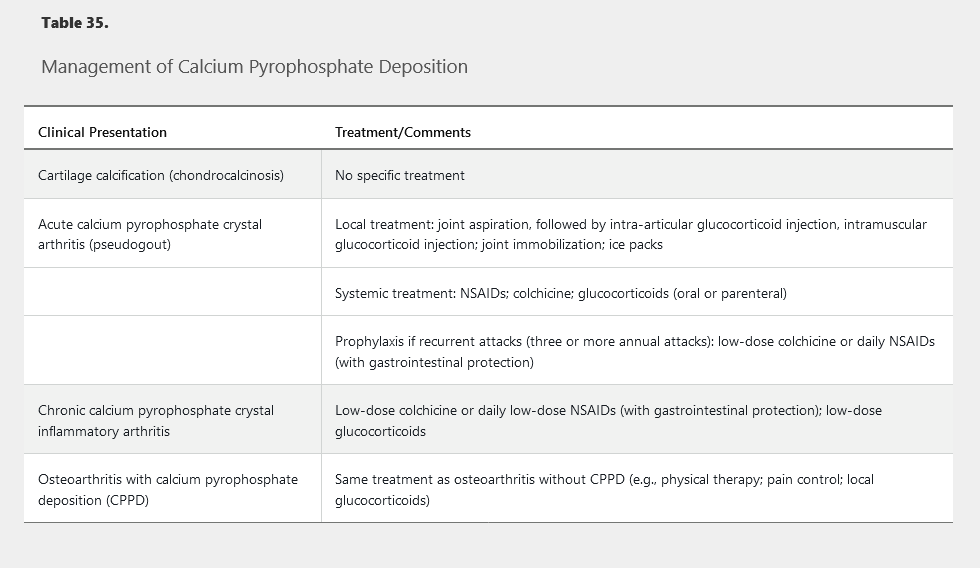

Because there is no known mechanism for dissolving or preventing the formation of articular CPP crystals, treatment aims at abrogating the inflammatory manifestations of the disease (Table 35).

Basic Calcium Phosphate Deposition

Basic calcium phosphate (BCP) deposition occurs in the elderly and forms in the articular cartilage; in contrast to CPPD, BCP crystals also often deposit periarticularly. BCP is thought to rarely cause inflammatory arthritis and periarthritis, most classically manifesting in elderly women as “Milwaukee shoulder,” an inflammatory periarthritis and arthritis of the shoulder, leading to progressive destruction of the rotator cuff and glenohumeral joint. Diagnosis is usually clinical; imaging of BCP crystals requires special stains and/or electron microscopy and is rarely performed.