Common Skin Infections

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Bacterial Skin Infections

Folliculitis

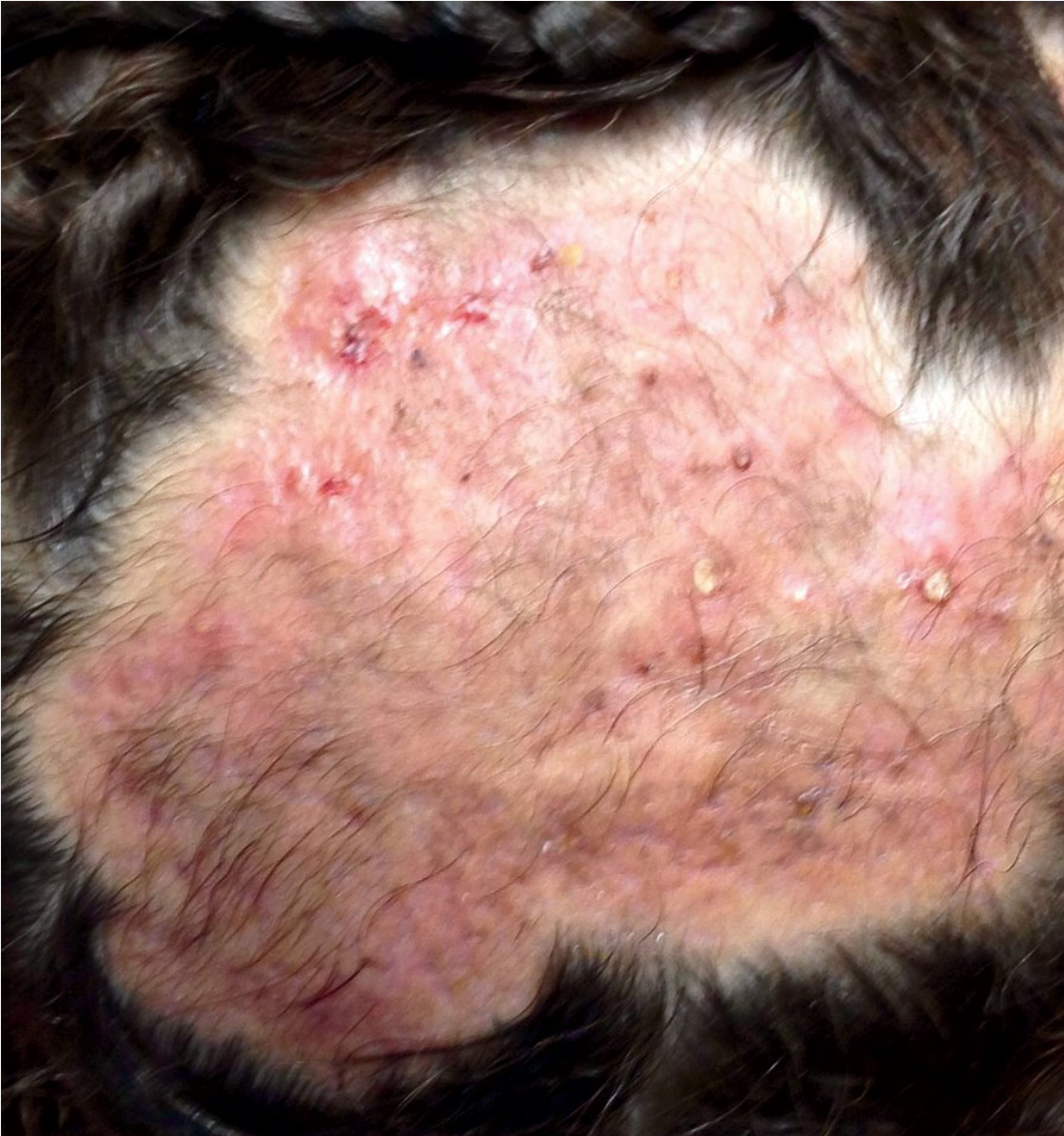

Folliculitis results from inflammation of the hair follicles. It typically presents as perifollicular erythematous papules and pustules on the face, scalp, trunk, and thigh; however, it can appear on any hair-bearing area of skin (Figure 34). Pruritus is a common symptom. Risk factors for folliculitis are occlusive dressings or clothing, increased sweating, obesity, and long-term topical glucocorticoid use.

Folliculitis can be noninfectious (HIV-associated eosinophilic folliculitis) or infectious. The most frequent cause of infectious folliculitis is Staphylococcus aureus. Other common infectious causes are gram-negative bacteria (Klebsiella species_, Enterobacter_ species) from prolonged antibiotic treatment for acne and from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is associated with hot tubs (Figure 35). Other causes of infectious folliculitis are the yeast Malassezia; viral folliculitis from herpes simplex or varicella zoster; and Demodex folliculitis, which is caused by a mite found in the pilosebaceous unit of normal skin, causing a rosacea-like rash. The diagnosis of folliculitis can be made from history and clinical presentation. Bacterial cultures can be performed from pustules but are usually not necessary. Skin biopsies can be performed when causes other than bacterial infection, such as fungal or herpetic infections, are suspected.

Treatment for bacterial folliculitis is antibacterial soaps or antibacterial washes such as chlorhexidine, but topical antibiotics also can be used. Systemic antibiotics, with coverage against S. aureus, may be required for refractory or recurrent folliculitis. Pseudomonas folliculitis is usually self-limited, although oral ciprofloxacin may be effective. Gram-negative folliculitis is usually treated with ampicillin or ciprofloxacin. Refractory cases require oral isotretinoin therapy. Malassezia folliculitis often responds to topical antifungal agents, although oral fluconazole might be more effective. Systemic antiviral agents should be used for herpetic folliculitis, whereas topical permethrin or oral ivermectin is effective treatment for Demodex folliculitis.

Abscesses/Furuncles/Carbuncles

Abscesses are soft tissue infections comprising collections of pus and bacteria within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. They present as painful, fluctuant, erythematous nodules (Figure 36). Furuncles (or boils) are deeper infections of the hair follicle involving the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Furuncles present as erythematous nodules with an overlying pustule. Multiple furuncles can coalesce into carbuncles, characterized by larger erythematous nodules with pus draining from multiple follicles. Carbuncles are typically located on the posterior neck, back, and the thighs. Fever and malaise can accompany carbuncles. S. aureus is the most common cause of abscesses, furuncles, and carbuncles, and there is an increasing prevalence of soft tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

Primary treatment for abscesses, furuncles, and carbuncles is incision and drainage. Gram stain and culture should be obtained from the purulent drainage when antibiotics are going to be administered (moderate and severe infections). Adjunctive oral antibiotic therapy is indicated for patients with moderate infections who have systemic signs of infection. Empiric treatment with an oral antibiotic active against MRSA such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline is recommended. Empiric treatment with agents such as vancomycin, daptomycin, or linezolid is recommended in immunocompromised patients, patients who fail incision and drainage plus oral antibiotics, or patients with hypotension and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (severe infection). Treatment is then adjusted based on sensitivities from the culture of the purulent drainage.

In the case of recurrent abscesses, other diagnoses should be considered, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, pilonidal cysts, or underlying conditions such as diabetes or HIV infection. Although MRSA decolonization in the community is controversial, the use of dilute bleach baths or chlorhexidine and topical mupirocin to the nares also may be considered for recurrent infections.

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Hospitalized Patients

There has been a significant increase in hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. MRSA infections have contributed to this increase and are associated with higher costs, longer hospitalizations, and higher morbidity and mortality rates.

Hospitalized patients are a common source of MRSA, but there is no consensus on effective screening measures. Active surveillance by performing screening cultures for MRSA is performed in many hospitals. Screening is usually performed by swabbing the nares, the most frequent site of colonization, although detection rates increase when screening of the nares is combined with cultures from the oropharynx and perineum. Screening policies also vary among hospitals. Some hospitals screen all admissions, whereas others screen only admissions to the ICU.

In patients who screen positive for MRSA, contact precautions using gown and gloves are effective in reducing transmission. Hand hygiene with soap and water or alcohol cleansers significantly reduces transmission and can decrease health care-associated infections. Decolonization of MRSA with daily chlorhexidine baths and the application of mupirocin to the nares twice a day for 5 days has shown to be effective in decreasing infections in the ICU.

In hospitalized patients with complicated skin and soft tissue infections, including purulent cellulitis, traumatic wound infections, and those who fail initial antibiotic therapy, therapy for MRSA should be considered pending culture data. Options include intravenous administration of vancomycin, daptomycin, telavancin, clindamycin, and linezolid. Oral linezolid is also an option.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a superficial infection of the epidermis most commonly caused by S. aureus or group A streptococci. Impetigo is classified as bullous or nonbullous impetigo. It is most commonly seen in children but can present in adults as well.

Bullous impetigo is usually caused by S. aureus, which produces exfoliative toxins targeting the adhesion molecule desmoglein-1 between keratinocytes. This results in a localized blister formation (Figure 37). This same toxin is responsible for the more extensive exfoliation seen in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Bullous impetigo presents as small vesicles that evolve into flaccid blisters. These blisters often rupture, leaving a collarette of scale and honey-colored crusted erosions. Nonbullous impetigo is more common and can be caused by either S. aureus, group A streptococci, or both. Nonbullous impetigo is characterized by erythematous papules or plaques with honey-colored crust (Figure 38). Satellite lesions are common. Nonbullous impetigo occurs on normal skin but can appear at areas of inflammatory conditions such as atopic dermatitis. Ecthyma is a variant of impetigo characterized by an ulcerative lesion with an overlying eschar that extends into the dermis and may be associated with lymphadenitis (Figure 39).

Clear, fluid-filled blisters with surrounding erythema on the legs of a patient with bullous impetigo.

Clear, fluid-filled blisters with surrounding erythema on the legs of a patient with bullous impetigo.

Nonbullous impetigo is a superficial infection characterized by a yellowish, crusted surface that may be caused by staphylococci or streptococci.

Nonbullous impetigo is a superficial infection characterized by a yellowish, crusted surface that may be caused by staphylococci or streptococci.

Superficial, saucer-shaped ulcers with overlying crusts are the classic findings of ecthyma. They almost always occur on the legs or feet and are usually caused by streptococci.

Superficial, saucer-shaped ulcers with overlying crusts are the classic findings of ecthyma. They almost always occur on the legs or feet and are usually caused by streptococci.

Diagnosis is typically made based on clinical appearance, but bacterial culture can be obtained from the blister fluid or exudative crust to identify the pathogen. Treatment consists of washing with soap and water and removal of the crust. Topical antibiotic treatment with mupirocin or retapamulin is effective in most cases of impetigo. Oral antibiotics are recommended for patients with widespread infection if outbreaks occur involving multiple people as well as in cases of ecthyma. Recommended antibiotics are cephalexin or dicloxacillin, unless MRSA is suspected or confirmed.

Topical neomycin/polymyxin B/bacitracin does have some activity again S. aureus and streptococci, but it is not as effective as mupirocin. Also, there is a higher risk of allergic contact dermatitis with topical antibiotics containing neomycin and bacitracin, so this would not be the most appropriate treatment in this patient.

Cellulitis/Erysipelas

Cellulitis and erysipelas are both nonpurulent, superficial, spreading skin infections. Cellulitis typically refers to an infection involving the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Although erysipelas can be considered synonymous with cellulitis, it is often used to describe an infection limited to the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics. Erysipelas is also a term used when cellulitis only involves the face. Both cellulitis and erysipelas result from compromise in the skin barrier (trauma, ulcers, lymphedema, peripheral vascular disease, or previous cellulitis) allowing bacterial entry. The clinical presentation of cellulitis includes spreading patches of erythema with associated tenderness, warmth, and edema. It is usually found unilaterally on a lower extremity (Figure 40). Erysipelas classically has a more demarcated erythematous border than cellulitis. Systemic symptoms such as fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis can be present in both. There are several conditions that can mimic cellulitis (Table 11). The most common cause of cellulitis is group A streptococci followed by S. aureus. Blood cultures and skin biopsies are not usually needed.

For immunocompetent patients with mild cellulitis/erysipelas (no systemic signs of infection), empiric oral therapy directed against streptococci is recommended with penicillin, amoxicillin, cephalexin, dicloxacillin, or clindamycin. In patients with systemic signs of infection, intravenous treatment with penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin is recommended. In patients who have failed oral antibiotic therapy, who are immunocompromised, who have systemic inflammatory response syndrome and hypotension, or who have evidence of deeper necrotizing infection with findings such as bullae and desquamation, surgical evaluation for debridement and empiric broad spectrum antibiotic therapy with vancomycin plus either imipenem, meropenem, or piperacillin-tazobactam are recommended. Treatment is then adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results from lesion-associated specimens.

Patients with cellulitis have annual recurrence rates of 8% to 20%. Treating predisposing factors such as edema, obesity, diabetes, and venous insufficiency might decrease recurrence. Examination and treatment of the interdigital toe spaces for tinea infection, maceration, and fissuring can also prevent recurrence. The prophylactic use of antibiotics is effective in preventing recurrence of cellulitis and should be considered in patients with more than three episodes of cellulitis per year.

Pitted Keratolysis

Pitted keratolysis is a bacterial infection of the soles of the feet, or (less commonly) the palms of the hand, with characteristic appearance and odor. As the name suggests, the infection manifests as scale and pitting of the skin surface. These pits may coalesce into larger erosions (Figure 41). In the United States, the infection is most common among patients with hyperhidrosis and prolonged occlusion of the feet (athletes, military personnel, laborers). Other than appearance and odor, symptoms are usually minimal and limited to mild pruritus or slight discomfort. Treatment is with topical antibacterial therapy such as clindamycin, erythromycin, or over-the-counter benzoyl peroxide preparations. In addition, the use of topical antiperspirants (aluminum hydroxide) and frequent changing and washing of socks should be used to keep the feet (or hands) dry and clean. The most common causative organisms are Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, Corynebacterium species, and Actinomyces species.

Pitted keratolysis presents with small indented pits on a background of hyperkeratosis and results from increased sweating of the feet. It is a superficial bacterial infection most commonly due to Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, Corynebacterium or Actinomyces species.

Pitted keratolysis presents with small indented pits on a background of hyperkeratosis and results from increased sweating of the feet. It is a superficial bacterial infection most commonly due to Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, Corynebacterium or Actinomyces species.

Erythrasma

Erythrasma is a benign superficial bacterial infection of the skin. Afflicted patients report red-brown plaques in the groin, crural folds, gluteal folds, axillae, or less commonly in the interdigital or inframammary regions (Figure 42). The skin often has a thin, wrinkled appearance similar to cigarette paper, and patients are often misdiagnosed with a dermatophyte infection. Symptoms, limited to mild pruritus, are minimal in most patients. In the immunocompromised patient, severe invasive disease has been described. The causative organism is most commonly Corynebacterium minutissimum. This organism produces porphyrins that fluoresce a soft, coral red under a Wood lamp. C minutissimum, which is part of normal skin flora, can overgrow and cause disease under conditions of moisture and occlusion. Clinical appearance and fluorescence are the best means of diagnosis, as histopathology may be unremarkable and skin scrapings are not helpful. Treatment is best accomplished with oral erythromycin, clarithromycin, or tetracyclines, but cure with topical antibiotics is reported. Limited disease is treated with topical antibiotics (clindamycin 1%). Topical antifungals (miconazole) can also be used for limited disease as they can be effective for erythrasma and coexisting dermatophyte infection. Systemic therapy with oral macrolides (erythromycin or clarithromycin) is reserved for more extensive disease (multisite disease).

Erythrasma presents with sharply demarcated fine, pink-to-brown scaling patches that are typically found in skin-fold areas. The rash will fluoresce a coral red with Wood lamp illumination.

Erythrasma presents with sharply demarcated fine, pink-to-brown scaling patches that are typically found in skin-fold areas. The rash will fluoresce a coral red with Wood lamp illumination.

Superficial Fungal Infections

Tinea

Tinea (dermatophytosis) is classified based on body site that is involved: tinea pedis (“athlete's foot”) (Figure 43), tinea manuum (hand), tinea cruris (“jock itch”) (Figure 44), tinea capitis (scalp) (Figure 45), tinea faciei (face), and tinea corporis (body excluding the genital area or inguinal folds) (Figure 46). There are three species from the genera Epidermophyton, Microsporum, and Trichophyton that cause superficial fungal infections in humans, Trichophyton rubrum being the most common.

Erythematous patches with peripheral scale and associated onychomycosis (onychodystrophy with subungual debris of nails) in tinea pedis.

Erythematous patches with peripheral scale and associated onychomycosis (onychodystrophy with subungual debris of nails) in tinea pedis.

Kerion can be a result of tinea capitis infection and presents as painful boggy erythematous plaques with folliculitis and abscess formation.

Kerion can be a result of tinea capitis infection and presents as painful boggy erythematous plaques with folliculitis and abscess formation.

Tinea corporis presents with a characteristic erythematous annular centrifugally growing patches with a raised rim of peripheral scale.

Tinea corporis presents with a characteristic erythematous annular centrifugally growing patches with a raised rim of peripheral scale.

Dermatophytosis can also be classified as anthropophilic, zoophilic, and geophilic, based on host and mode of transmission. Anthropophilic dermatophytes are found in humans, cause little inflammation, and are transmitted from human to human or through fomites. Zoophilic dermatophytes are transmitted from animals to humans from direct or indirect contact and cause inflammation and occasionally cause suppurative dermatophytosis. Geophilic dermatophytes only occasionally infect humans through direct contact but also cause inflammatory dermatophytosis. Infection is more prevalent in hot and humid climates and in patients who are immunocompromised, particularly those taking chronic glucocorticoid therapy.

The characteristic clinical presentation of tinea corporis, cruris, and faciei is annular scaly patches with central clearing and varying degrees of inflammation. Tinea cruris spares the scrotum in contrast to candida intertrigo, which is in the differential diagnoses. Concomitant tinea pedis and cruris are not uncommon. In tinea capitis, the invasion of the hair follicle leads to small broken hairs with the surrounding scalp showing erythematous scaly patches with varying degrees of crust and numbers of pustules. Occipital adenopathy is frequently seen. The chronic form of tinea pedis and tinea manuum presents as mildly pruritic scaly patches involving most of the palms and soles in a “moccasin” or “glove” distribution (Figure 47). One hand and two feet tinea is a characteristic pattern of involvement. Tinea pedis can have a more acute form with 1- to 2-mm vesicles and can be extremely pruritic. The interdigital variant of tinea pedis shows fissures and maceration in the folds. Tinea incognito refers to tinea that has been erroneously treated with topical glucocorticoids, which initially decreases pruritus, but leads to a clinical presentation that is less inflammatory and can result in invasion of the follicular epithelium.

Mildly erythematous patches with fine scale that are well demarcated and are confined to the lateral foot, heel, and sole characteristic of “moccasin” type tinea pedis.

Mildly erythematous patches with fine scale that are well demarcated and are confined to the lateral foot, heel, and sole characteristic of “moccasin” type tinea pedis.

Tinea can be suspected based on clinical presentation and pruritus; however, diagnosis is based on visualization by microscopic examination of branching hyphae in the keratin (scale) using a potassium hydroxide preparation. To confirm the diagnosis, a fungal culture can be performed, which provides species identification, and is the preferred method for diagnosing tinea capitis. Hair shafts should be included in the specimen.

Dermatophytosis of non-hair–bearing skin with limited involvement can be treated topically with imidazole creams, such as miconazole, clotrimazole, and ketoconazole, applied once to twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks, ensuring that the application extends a few centimeters beyond the advancing border. Other topical agents including terbinafine 1% and ciclopiroxolamine 0.77% can also be used. Unlike superficial fungal infections caused by Candida, dermatophytes do not respond to topical nystatin. Combined antifungal agents and topical glucocorticoids should be avoided as they can lead to increased recurrences and treatment failures. Dermatophytosis of hair-bearing skin, including tinea capitis, or those with recurrent or extensive skin involvement, should be treated with oral antifungal agents such as terbinafine or itraconazole. Tinea should be treated to prevent skin breakdown, which can be an entry port for bacterial infection.

Oral antifungal therapy with terbinafine or an azole antifungal agent such as itraconazole or fluconazole may be necessary for treating tinea capitis, onychomycosis, Majocchi granuloma (a granulomatous response to dermatophyte infection in the dermis and hair follicles), or extensive infection. Oral ketoconazole no longer has an indication for superficial fungal infection because of severe and sometimes fatal idiosyncratic liver toxicity. In addition, ketoconazole is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 resulting in significant drug interactions. Prolonged use of ketoconazole also may result in adrenal gland suppression.

Pityriasis Versicolor

Pityriasis versicolor or tinea versicolor is caused by commensal lipophilic fungi that live in the hair follicles and stratum corneum. Pityriasis versicolor is one of the most common, chronic, superficial fungal infections and is typically found in young adults. Caused by Malassezia furfur, pityriasis versicolor is most common in warm, humid environments. It presents as asymptomatic, oval-to-round, minimally scaly, hyperpigmented or hypopigmented macules that can coalesce into patches on the trunk and upper extremities (Figure 48).

Hypopigmented scaly macules coalescing into patches on the back characteristic of pityriasis versicolor.

Hypopigmented scaly macules coalescing into patches on the back characteristic of pityriasis versicolor.

The diagnosis of pityriasis versicolor can often be made by clinical presentation but may be confirmed by visualization of short rod-shaped hyphae and round yeast (“spaghetti and meatballs”) on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using a potassium hydroxide preparation. Topical treatment using ketoconazole 2% shampoo or selenium sulfide suspension is effective. Either treatment should be applied from the upper neck to the thighs and used to wash the scalp. Oral itraconazole can be used for those with extensive disease or frequent recurrences. Because recurrences are high, weekly use of topical treatments can be preventive.

Pityriasis Rosea

This patient has a widespread outbreak of pruritic plaques consistent with pityriasis rosea (PR). PR predominantly affects the trunk, neck, and proximal limbs and is most common in adolescents and young adults. It is thought to have a viral etiology, and is often associated with a nonspecific, mild, flu-like prodrome. PR typically begins with a single, large, scaly, salmon-colored lesion (herald patch), but numerous smaller lesions develop rapidly thereafter. The secondary lesions occasionally may be oriented parallel to skinfolds in a "Christmas tree" pattern.

The diagnosis of PR is usually based on clinical features. Skin scrapings may be helpful for differentiating an isolated herald patch from tinea corporis, although the acute onset usually makes the distinction obvious. PR is a self-limited disorder, but the lesions may take a few months to resolve. Pruritus can be managed with topical glucocorticoids or oral antihistamines. Phototherapy can be considered for more severe or persistent cases, but symptomatic therapy and simple reassurance is adequate for most patients.

Candidiasis

Candida species, in particular C. albicans, can cause superficial infections in moist occluded skin such as the intertriginous areas, oropharynx mucosa, and genitals, as well as disseminated disease in immunocompromised, hospitalized patients (see MKSAP 18 Infectious Disease). Antibiotic therapy increases the number of colonizing organisms present in skin and mucous membranes leading to an increased risk of infection.

Intertrigo is an inflammatory skin disease that involves the axillae, inframammary, and inguinal folds (Figure 49). Candida is the most common secondary infection in intertrigo with obesity being an important risk factor. It presents as erythematous patches with satellite pustules that are often macerated. Diagnosis is frequently made on clinical grounds alone, but a potassium hydroxide preparation can show spores and pseudohyphae. For successful treatment, the area should be dry, and use of absorbent powers and zinc oxide paste can be helpful. Topical imidazoles and nystatin are generally effective, but recurrences are common. For widespread infection, oral fluconazole can be added.

Chronic paronychia is associated with irritants or allergens and is caused by frequent exposure to water. Exacerbations can be caused by Candida, and successful treatment includes treating the underlying irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, as well as treatment with topical or oral antifungal agents, depending on the severity of the infection (see Nail Disorders).

Viral Skin Infections

Herpes Simplex Virus

For both herpes simplex virus types 1 (HSV1) and 2 (HSV2), transmission usually occurs by direct contact with infected secretions, skin lesions, or asymptomatic shedding. Both HSV1 and HSV2 can cause oral and genital lesions; however, infections with HSV1 are usually above the waist (oral, facial), whereas HSV2 infections are usually below the waist (genital). The seroprevalence of HSV increases with age, with HSV1 IgG antibodies being present in most adults. HSV2 seroprevalence increases with the number of sexual partners and high-risk sexual behaviors.

HSV causes a clinically unapparent primary infection through skin and mucous membranes where it replicates locally. This is followed by a short viremia, and the virus subsequently establishes latency through retrograde axonal transport in sensory nerve ganglions. Characteristically, HSV1 is found in the trigeminal ganglion and HSV2 in the sacral ganglion. Recurrent lesions are caused by reactivation of the virus. Symptomatic primary and recurrent infections typically remain localized and are named according to the site of infection, regardless of the HSV subtype responsible: herpetic gingivostomatitis, herpes labialis (“cold sore”), herpes facialis, and herpes genitalis.

The classic presentation is a group of painful, small vesicles on an erythematous base, transitioning to pustules and subsequent crusting of the lesions over time (Figure 50). Erosions or ulcers may also develop. HSV is the most common cause of painful genital ulcers, although chancroid also causes painful ulcers. Other infections (syphilis, granuloma inguinale, lymphogranuloma venereum) often cause nonpainful ulcerations (see MKSAP 18 Infectious Disease). However, a diagnosis based on the presence or absence of pain may be misleading.

With any sexually transmitted infection, HIV testing also is important. Symptomatic primary infections are usually more severe and of longer duration than recurrences. There is associated burning, tingling, and pain, which can be a prodrome in recurrences. Reactivation is higher in persons who are immunocompromised, and it can be triggered by trauma, ultraviolet light exposure, psychosocial stress, and fever. In herpes genitalis, recurrences are more frequent with HSV2 and in women, and asymptomatic shedding occurs in most patients with HSV2 but not HSV1.

The diagnosis is typically made on clinical grounds; however, for distinction between subtypes of HSV or from varicella zoster virus, other methods can be used (Table 12). Oral antiviral agents (acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir) can be used to treat primary infections, episodic or secondary recurrences, and as suppression or prophylaxis for patients with six or more recurrences per year. Oral antiviral agents are most effective when started during the prodrome of recurrences. Dosing varies for primary, secondary, and prophylaxis, as well as by site of infection and for immunocompromised patients. Topical therapies are less effective in improving symptoms and reducing disease duration.

Varicella/Herpes Zoster

Related Question

- Question 6

Varicella-zoster virus is a DNA virus that causes varicella (chickenpox), which is an acute illness with fever and an eruption of vesicles on an erythematous base that is transmitted by respiratory droplets (Figure 51). After primary infection, the virus remains latent in the dorsal root or cranial ganglia. Reactivation causes herpes zoster or shingles (Figure 52). Prodromal symptoms, such as burning, stinging, or tingling, often occur in a localized region, followed by a dermatomal eruption of grouped vesicles or pustules on an erythematous base. The most common dermatomes affected are in the thoracic region. With involvement of the first division of the trigeminal nerve (forehead extending over upper eyelid, or nasal tip involvement), ophthalmologic evaluation is mandatory as herpes zoster ophthalmicus and possible blindness can result. If vesicles are noted in the external ear canal, evaluation by an otolaryngologist may be required as peripheral facial paralysis and auditory/vestibular symptoms can occur (Ramsay Hunt syndrome).

Herpes zoster can be complicated by postherpetic neuralgia and has been associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease. Postherpetic neuralgia is defined as chronic neuropathic pain that persists for 3 months or more after the initial onset of herpes zoster. The risk, severity, and complications of herpes zoster, in particular postherpetic neuralgia, are increased in older patients, those with greater initial pain and more severe infection, and possibly in patients that are immunosuppressed or on immunosuppressive or immunomodulating medications.

Diagnosis of herpes zoster can usually be made by characteristic dermatomal presentation. For unusual cases or when the distinction between herpes simplex virus and herpes zoster is required, ancillary studies are available (see Table 12). Oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir is effective for treating herpes zoster if initiated within 72 hours of presentation and can shorten the disease course as well as help prevent postherpetic neuralgia. Current evidence is insufficient to support the addition of glucocorticoids with acyclovir to improve quality of life or the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia.

A recombinant zoster vaccine is now preferred to the live attenuated zoster vaccine in adults 60 years and older to prevent or attenuate illness caused by herpes zoster infection and to reduce the risk of postherpetic neuralgia. For individuals previously immunized with the live attenuated vaccine, revaccination with the recombinant vaccine is recommended.

Warts

Warts (verruca and condyloma) are caused by a human papillomavirus (HPV), which is ubiquitous. There are numerous HPV subtypes, but certain ones are associated with specific clinical lesions and are more common at certain sites (Table 13). Verruca vulgaris (common warts) are skin-colored digitate papules with thrombosed capillaries. Verruca plana (flat warts) are skin-colored, flat-topped papules (Figure 53). Condyloma acuminata (genital warts) are smooth to digitate papules that are skin-colored to tan (Figure 54). Verruca plantaris/palmaris (plantar/palmar warts) are exo-/endophytic papules with thrombosed capillaries manifesting as black dots when the top of the wart is pared down. HPV infection can occur at any age but is typically seen in children and young adults. Larger, more numerous lesions that are recalcitrant to treatment can be seen in immunocompromised persons.

Common warts are due to human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. They are especially common in individuals who handle meat, poultry, and fish, as well as those with atopic dermatitis. Immunosuppressed individuals (eg, HIV) also commonly develop warts.

Diagnosis is clinical. Warts are usually self-limited; however, in severe cases, including those with a protracted course or in immunocompromised persons, destructive treatments can be used. Location of the lesions has to be taken into account when selecting treatment, and can be associated with pigment change or scarring. Numerous treatments (salicylic acid, cryotherapy, tricarboxylic acid, cantharidin, and podophyllin) geared at destroying infected keratinocytes are available. All of these treatments should be repeated every 3 to 4 weeks until resolution. Larger lesions should be pared prior to treatment.

HPV vaccination is recommended for young persons to prevent cervical and anal carcinoma. Anogenital warts may also be prevented if the vaccine is effective against HPV 6 and 11 (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine).

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by a poxvirus. Infection occurs in children, in adults as a sexually transmitted disease, and in patients with AIDS. The lesions are white-to-yellow smooth papules with an umbilicated center (Figure 55). Many patients develop a surrounding eczematous host response. They can be located anywhere on the skin, but in adults the genital area is typically involved, whereas in patients with AIDS the face is the most common area of infection and the lesions tend to be larger. Transmission is by direct contact or by fomites.

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection resulting from poxvirus infection. It occurs in young children and sexually active adults. It presents as firm, umbilicated yellow papules with varying degrees of surrounding erythema.

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection resulting from poxvirus infection. It occurs in young children and sexually active adults. It presents as firm, umbilicated yellow papules with varying degrees of surrounding erythema.

Diagnosis is based on clinical appearance, but skin biopsy on equivocal cases shows eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions within keratinocytes. Molluscum contagiosum is usually self-limited, but in severe cases, those with a protracted course, or in immunocompromised persons, destructive modalities or topical medications can be used. Any of these treatments can be associated with scarring and pigment change. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, tricarboxylic acid, cantharidin, and podophyllin. Medical treatments consist of topical tretinoin and topical imiquimod.