Common Rashes

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Eczematous Dermatoses

Eczematous dermatoses are common inflammatory conditions that present as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques that may show weeping or dry scaling at various stages. These dermatoses lead to impaired skin barrier function, often allowing for secondary bacterial infections.

Treatment includes avoidance of known triggers, use of mild cleansers followed by immediate application of fragrance-free emollients and topical anti-inflammatory medications.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis commonly presents on the face and flexural surfaces, such as the popliteal and antecubital fossae (Figure 2). Excoriations and thickening (lichenification) of the skin from scratching often accompany other signs of the atopic triad (allergic rhinitis, asthma, and eczema). The pathogenesis is thought to be caused by a mutation in filaggrin, a protein in the epidermis important in the barrier function of the skin. Affected skin is often secondarily infected by Staphylococcus aureus due to a decrease in antimicrobial peptides. The use of fragrance-free, non–soap-based cleansers and moisturizers along with topical glucocorticoids is the primary treatment.

Atopic dermatitis showing skin thickening (lichenification) due to scratching and dry scaling in the popliteal flexure.

Atopic dermatitis showing skin thickening (lichenification) due to scratching and dry scaling in the popliteal flexure.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, are steroid-sparing agents useful for areas such as the face and skin folds where permanent atrophy from long-term or potent topical glucocorticoid use is a concern.

Contact Dermatitis

Pathophysiology and Evaluation

There are two types of contact dermatitis: allergic and irritant. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV, T-cell–mediated, delayed hypersensitivity reaction. On re-exposure to a specific allergen, sensitized T-cells trigger an inflammatory cascade, leading to an eczematous eruption at the site of contact; rarely, a widespread eruption (id reaction) may occur. Irritant contact dermatitis is more common than allergic contact dermatitis and is not immune mediated. Irritant contact dermatitis occurs from direct damage to the skin from harsh chemicals, soaps, or detergents.

Discovering the cause of contact dermatitis is essential to its treatment and prevention. A detailed history can help identify the cause, but often epicutaneous patch testing is needed to identify the source (Figure 3). For patch testing, a number of standardized chemicals are applied to the skin and removed 48 hours later. Evaluation is performed at the time of patch removal and again 5 to 7 days later to assess for redness and eczematous reaction at any of the sites. Because allergies can develop over time, a long history of using a product without a problem does not exclude that product as a potential trigger.

Common Causes of Allergic Dermatitis

Urushiol, the allergen that is a common cause of allergic contact dermatitis, is found in plants such as poison ivy, oak, and sumac, which are members of the genus Toxicodendron (formerly Rhus). Clinically, it presents with intensely pruritic, often linear, vesicular papules, plaques, and vesicles (Figure 4). Lesions can present at different locations at different times up to 14 days after exposure in sensitized patients. Fluid from vesicles and blisters is not antigenic. After exposure, patients should remove any contaminated clothing and gently wash the skin with soap and water. It is critical for those sensitive to these antigens to avoid inhaling any smoke resulting from the unintentional or inadvertent burning of these plants as the smoke contains allergenic plant particles.

Nickel, another common allergen, is commonly found in everyday items such as jewelry, zippers, cell phones, and even medical devices. Eczematous dermatitis of the lower abdomen is a common presentation of a nickel allergy from a snap or belt buckle. Patients may use a commercially available nickel test kit to identify items that contain nickel.

Fragrances are also common allergens found in many cosmetic products, moisturizers, and detergents. They may also be present as flavoring agents of toothpastes, mouthwashes, and food beverages.

Neomycin and bacitracin are commonly used for wound care. They can cause an allergic contact dermatitis that mimics a wound infection. Given the prevalence of sensitivity to these products, patients should use plain petrolatum in place of topical antibiotics to aid healing of clean wounds.

Almost all household cleansers and personal hygiene products contain preservatives that can produce allergic contact dermatitis. Certain occupations also are at increased risk of allergic contact dermatitis (Table 6).

Treatment of Contact Dermatitis

Avoidance of the causative agent is preventive and curative. Topical glucocorticoids are used while the patient and clinician work together to identify and eliminate the source. Severe allergic contact eruptions may necessitate a 2- to 3-week taper of systemic glucocorticoids. Because of the risk of rebound dermatitis, shorter courses of systemic glucocorticoids are not recommended.

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus is a condition caused by repetitive scratching or rubbing. Predisposing conditions include atopic dermatitis, xerosis, and psychiatric conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lichen simplex chronicus manifests as thickened plaques with erythema and hyperpigmentation (Figure 5). Exaggerated skin markings are seen on the surface of the skin as well. Common sites include the genitals, back of the neck, wrists, ankles, and lower legs. Lichen simplex chronicus is treated with moisturizers, high and ultrapotent topical glucocorticoids, and intralesional glucocorticoid injections.

Intertrigo

Intertrigo is dermatitis involving adjacent skin folds (axillary, inframammary, abdominal, and inguinal) (Figure 6). Predisposing conditions include obesity, friction, occlusion, and factors that interfere with immune response, such as diabetes mellitus. Intertrigo presents with erythematous, macerated plaques. Secondary infection with Candida is common and may be suspected by the presence of multiple small red papules and pustules that surround the main rash (satellite pustules).

Treatment of intertrigo consists of drying the area and use of agents such as antifungal powder, to reduce moisture and maceration and to prevent secondary yeast infection. Short courses of low-potency topical glucocorticoids may be added to treat the associated inflammation. If secondary Candida infection is suspected, concomitant treatment with topical antifungal agents can be added.

Hand Dermatitis

Hand dermatitis often results from a combination of causes such as excessive hand washing, contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, or dyshidrotic eczema (pompholyx). It is most commonly seen in patients who hold jobs involving frequent or prolonged exposure to water, chemicals, and occlusive gloves (health care, house cleaning, food preparation, hairstyling). It is characterized by pruritic, erythematous plaques on the palmar and dorsal hands, which can lead to fissuring and lichenification over time (Figure 7). Dyshidrotic eczema presents with vesicles on the palms and sides of the fingers.

The differential diagnosis of hand eczema includes tinea, psoriasis, and scabies. The entire body should be examined for other rashes that may help differentiate hand dermatitis from these other rashes. If tinea is suspected, the feet should be examined for tinea pedis and onychomycosis (two feet-one hand syndrome).

Treatment includes topical emollients such as petrolatum. A potent topical glucocorticoid may be necessary during flares. Triggers should be identified and avoided, and hand washing minimized. White cotton glove liners are recommended inside of rubber gloves when working with chemicals and water.

Xerotic Eczema

Also called eczema craquelé or asteatotic eczema, xerotic dermatitis is often seen on the lower extremities of older persons. Dry weather and excessive bathing are known inciting factors. The lesions are erythematous with plate-like cracked scale, often resembling a dried up creek bed (Figure 8). Although aging is the most common cause, hypothyroidism or medications such as diuretics may be implicated.

Treatment consists of thick emollients and potent topical glucocorticoids for a 2- to 3-week course.

Nummular Eczema

Nummular eczema, also called discoid eczema, is characterized by coin-shaped, pruritic, scaly plaques (Figure 9). This form of eczema is common on the extremities. The round shape may lead to confusion between this form of eczema and other conditions, such as tinea corporis, nummular psoriasis, or contact dermatitis. Tinea corporis often has a partially cleared center and scaling at the periphery. Psoriasis is often located on the elbows, knees, scalp, or intergluteal cleft and has larger, thicker white scale. Contact dermatitis may be suggested by location on the body that matches contact with a potential allergen.

Potent topical glucocorticoids and emollients are the preferred treatment.

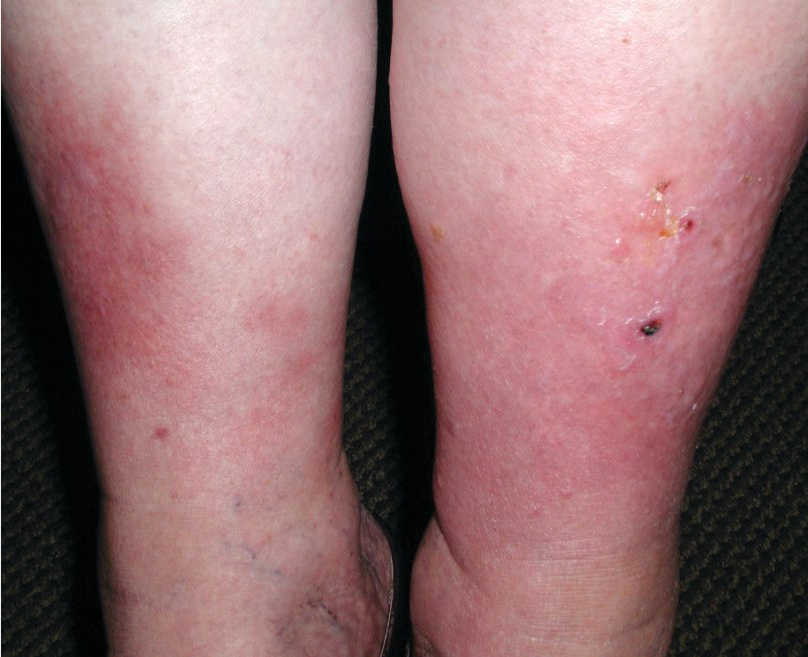

Stasis Dermatitis

Stasis dermatitis, which can be very pruritic and erythematous, is common in patients with chronic lower extremity edema, most commonly secondary to venous stasis (Figure 10). Symptoms are often bilateral with medial distal leg predominance, although it may be unilaterally symptomatic. Dependent edema, hyperpigmentation, and dilated veins are common associated findings. Symptoms can be managed topically with glucocorticoids and emollients, but the condition will not significantly improve until the edema is addressed with leg elevation and compression stockings. Because of a similar clinical presentation, stasis dermatitis can be misdiagnosed as cellulitis; however, cellulitis is usually unilateral, more acute in onset, and often associated with pain, leukocytosis, and occasionally fever.

Papulosquamous Dermatoses

Papulosquamous dermatoses are characterized by scaly papules and plaques caused by inflammation of the epidermis.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory dermatosis, typically presenting with thick, well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silvery scale (Figure 11). It affects approximately 2% to 4% of the population. The incidence peaks at age 30 to 39 years and again around 60 years. Disease severity can range drastically with some patients having only one plaque to an erythrodermic presentation involving more than 90% of the body surface area. Psoriasis has many clinical presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, or psoriasis vulgaris. Nail psoriasis can involve both fingernails and toenails. It presents clinically with nail pitting, onycholysis (separation of nail plate from nail bed), and “oil spots” (Figure 12). Other less common subtypes include guttate psoriasis (commonly seen in pediatric patients), palmoplantar psoriasis (frequently with pustules as the primary lesion), and inverse psoriasis (often seen without scale in the intertriginous areas). Inverse psoriasis is frequently misdiagnosed because of lack of scale, location (flexural), and resemblance to other common dermatologic conditions such as tinea, intertrigo, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Nail pitting, onycholysis, and yellow-red discoloration (oil spots) are often present when the nails are involved in psoriasis.

Nail pitting, onycholysis, and yellow-red discoloration (oil spots) are often present when the nails are involved in psoriasis.

Inverse psoriasis: red, thin plaque with variable scaling in axillae, under breast, perineum, intergluteal cleft

Inverse psoriasis: red, thin plaque with variable scaling in axillae, under breast, perineum, intergluteal cleft

Psoriasis is a systemic disease, not just a skin problem. Approximately 30% of patients have concurrent psoriatic arthritis. Patients with severe psoriasis also have a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of death among these patients, and chronic kidney disease. Psoriasis is associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome. The proposed link between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease is thought to be inflammation with similar cytokines involved in both psoriatic and atherosclerotic plaques.

Smoking tobacco may worsen psoriasis, and all patients should be counseled against smoking especially because of the elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. The pharmacologic treatment of psoriasis depends on the severity of the disease. Topical glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment for localized disease. Topical vitamin D analogues are also used as monotherapy or in combination with topical glucocorticoids. In patients with skin involvement of greater than 10% body surface area (severe psoriasis), psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis recalcitrant to topical treatments, or psoriasis in locations such as scalp or groin, systemic therapies, including phototherapy and traditional treatments such as methotrexate, acitretin, and cyclosporine, should be considered. Newer systemic therapies are the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor (apremilast) and biologic agents (tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, interleukin-12/interleukin-23 inhibitors, and interleukin-17 inhibitors). These treatments target the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Psoriasis is usually graded as mild (affecting < 3% of the body), moderate (affecting 3%-10% of the body), or severe (affecting > 10% of the body). Treatment modalities are chosen based on the severity of disease, sites of involvement, relevant comorbidities, patient preference, efficacy, and patient response. Those with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis (as in this patient) should be treated initially with topical corticosteroids and emollients. Alternate therapies include tar, topical retinoids (eg, tazarotene), and topical vitamin D (eg, calcipotriene, calcitriol). Although topical vitamin D analogues are effective as monotherapy, combination therapy with topical corticosteroids is more effective than either therapy alone.

For facial or intertriginous involvement, topical tacrolimus (Choice E) or pimecrolimus may be used as a corticosteroid-sparing agent as chronic corticosteroid use in these areas can cause harmful skin effects such as atrophy, telangiectasia, and perioral dermatitis.

In consultation with a dermatologist, patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis should be treated initially with phototherapy (Choice C). Patients with contraindications to phototherapy (eg, history of melanoma, extensive nonmelanoma skin cancer), who fail phototherapy, or who have moderate-to-severe disease and psoriatic arthritis should be treated with a systemic agent. Systemic therapy includes immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologic agents (eg, etanercept) (Choices A and B).

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a T-cell–mediated disease classically presenting as pruritic, flat-topped, violaceous papules, often on the flexural surfaces of the extremities (wrists and ankles) and mucous membranes (Figure 13). This disease is fairly common with an incidence of 0.2% to 1% in adults. Other variants include mucosal, genital, bullous, atrophic, and hypertrophic lichen planus. Mucosal lesions have lacy white streaks (Wickham striae) or erosions and ulcerations. There can also be nail thickening and onycholysis, which can lead to scarring around the cuticle (dorsal pterygium).

Lichen planus tends to resolve over 1 to 2 years, although oral and nail lichen planus are more persistent. Some but not all studies have shown an increased prevalence of hepatitis C infection in patients with lichen planus. Squamous cell carcinoma transformation has been reported most commonly in erosive oral lichen planus and hypertrophic lichen planus.

Potent topical glucocorticoids are effective in most patients. Systemic glucocorticoids, oral retinoids, sulfasalazine, and phototherapy are reserved for severe cutaneous or persistent oral disease.

Pityriasis Rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a common rash that may be related to reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 or 7. Pityriasis rosea begins as a single annular patch or plaque with fine scaling (the herald patch), typically on the trunk, followed by numerous smaller skin-colored to pink papules and plaques erupting along skin cleavage lines (Figure 14). This distribution on the posterior thorax can resemble a “fir tree” pattern. The herald patch is absent in up to 50% of cases, but when present it usually precedes the smaller plaques by several days up to 2 weeks.

Most patients do not need treatment, as these lesions are often asymptomatic and resolve over a few weeks to months. For patients with pruritus, a topical glucocorticoid and/or oral antihistamine can be used for symptomatic relief. Macrolide antibiotics, acyclovir, and phototherapy have all been reported to speed up resolution, but these treatments are generally not recommended. It is important to rule out secondary syphilis, which can look similar, but typically also involves the palms and soles and is usually associated with generalized lymphadenopathy.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common condition characterized by greasy yellow, scaly, erythematous patches in seborrheic areas (the scalp, face, ears, upper chest, axillae, and inguinal folds) (Figure 15). Specific areas of involvement on the face are the eyebrows, medial aspects of the cheeks, inter-eyebrow region, and the nasal ala. Men are more frequently affected than women. This disease is believed to be caused by a heightened sensitivity to lipophilic yeasts such as Malassezia. It is more prevalent in patients who are immunocompromised, such as those with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant patients. In HIV/AIDS patients, the severity of seborrheic dermatitis is inversely correlated with the CD4 counts, may extend beyond typical locations, and may be difficult to control. Patients with Parkinson disease or Down syndrome also have a higher prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis. Diagnosis is made clinically based on the distribution and appearance. Factors contributing to flares include sleep deprivation and stress.

Seborrheic dermatitis, with fine, oily scale around the medial eyebrows.

Seborrheic dermatitis, with fine, oily scale around the medial eyebrows.

Treatment includes over-the-counter medications such as selenium sulfide or zinc pyrithione shampoos. Ketoconazole shampoo and cream are effective as well. Patients should be counseled to apply the shampoo on the skin and allow it to sit for 5 minutes before washing off. Weak or low-potency topical glucocorticoids can be used in combination with antifungal treatments when severely inflamed. Oral ketoconazole is not recommended owing to the risk of liver and adrenal gland toxicity, although other oral antifungal agents may be used for severe or refractory disease. If conventional therapies are not effective, other diagnoses must be considered including rosacea, lupus erythematosus, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis.

Miliaria

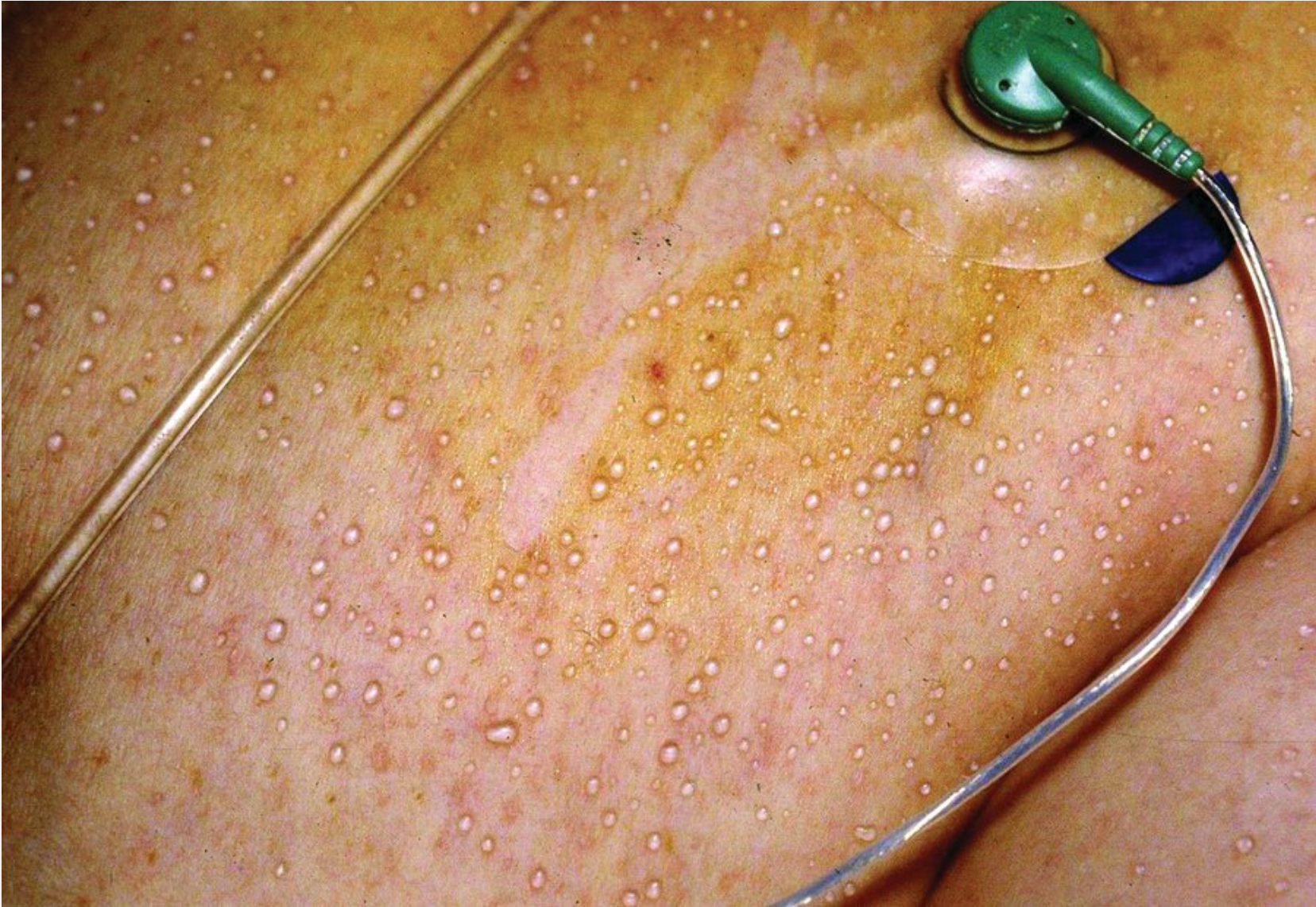

Miliaria (prickly heat, heat rash) is caused by the occlusion and subsequent rupture of the eccrine sweat ducts at various levels. An overgrowth of Staphylococcus epidermis may contribute to the pathogenesis in miliaria. Clinically, it presents as numerous nonfollicular 1- to 3-mm papules or pustules that can arise with any condition causing sweating and skin occlusion. Miliaria can be subtyped by the level at which the eccrine sweat glands are occluded. Miliaria crystallina is caused by an occlusion at the stratum corneum and is characterized by asymptomatic clear subcorneal vesicles that can be easily ruptured (Figure 16). This tends to be more common in neonates. Miliaria pustulosa describes the condition when vesicles have turbid fluid within them (Figure 17). Miliaria rubra is characterized by multiple small pink papules. It is the most common form and usually found on the trunk, particularly the back. It is the result of a deeper occlusion of the eccrine duct causing an intraepidermal-dermal vesicle.

Miliaria crystallina with clear, fragile vesicles without inflammation.

Miliaria crystallina with clear, fragile vesicles without inflammation.

Miliaria pustulosa showing numerous 1-mm non-inflammatory pustules on the back of a hospitalized patient, seen in this image as small white dots.

Miliaria pustulosa showing numerous 1-mm non-inflammatory pustules on the back of a hospitalized patient, seen in this image as small white dots.

Supportive therapy involves eliminating predisposing factors such as sweating and removal of occluding agents or conditions. Low-potency topical glucocorticoids can be used sparingly if symptomatic.

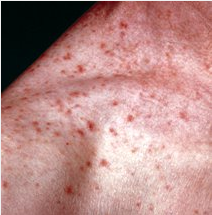

Transient Acantholytic Dermatosis

Transient acantholytic dermatosis, also known as Grover disease, is a relatively common benign eruption that is most often seen in middle-aged to elderly white men. The eruption presents as discrete papules, some of which may be scaly, and papulovesicles on the trunk (Figure 18). Symptomatically there are varying degrees of pruritus that may be associated with seasonal flares during the winter and spring. The cause is unknown, but there are specific conditions that are commonly associated including chronic sun damage, eczema, and psoriasis. Transient acantholytic dermatosis can be triggered by dry skin, sweating, increased body temperature, acute sun exposure, certain medications, and internal neoplasms. The diagnosis can be confirmed by a skin biopsy that characteristically shows acantholysis of the epidermis with variable amounts of dyskeratosis.

A patient with transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease) showing recurrent outbreaks of pruritic, red papules, some of which are scaly, on the back. The image also shows numerous tan-colored seborrheic keratoses.

A patient with transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease) showing recurrent outbreaks of pruritic, red papules, some of which are scaly, on the back. The image also shows numerous tan-colored seborrheic keratoses.

Treatment includes moisturizers, emollients, and medium- to high-potency topical glucocorticoids. For severe and recalcitrant cases, oral retinoids, in particular isotretinoin, and psoralen with ultraviolet A (PUVA) can be used; neither is FDA approved for transient acantholytic dermatosis.