Colorectal Neoplasia

- related: GI, metastatic colon cancer to liver

- tags: #GI

Colorectal Neoplasia

Epidemiology

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and second most common cause of cancer-related mortality among men and women in the United States. Its annual incidence rate among adults in the United States is 42 cases per 100,000, and its mortality rate is 15.5 deaths per 100,000. The incidence of colorectal cancer is approximately 25% higher in men than in women.

The incidence and mortality rates for colorectal cancer have decreased over the past 30 years, largely because of early detection through screening and changes in risk factors (such as decreased smoking). However, there has been a steady increase in the number of colorectal cancer cases in patients younger than age 50 years, for unknown reasons. Survival rates are greater than 90% when the disease is localized, underscoring the importance of early detection. Between 20% and 53% of adults older than age 50 years have premalignant adenomas of the colon detected on screening, and 3% to 8% of the adenomas have advanced histological features. Despite strong evidence supporting colorectal cancer screening, only about 59% of Americans older than age 50 years are up-to-date for recommended testing.

Pathogenesis

Colorectal cancer develops through one of three mechanisms: chromosomal instability, microsatellite instability, and serrated neoplasia.

Chromosomal instability is the most common mechanism, accounting for approximately 85% of colorectal cancers. Chromosomal instability is characterized by cancer cells that gain or lose whole chromosomes or large fractions of chromosomes (aneuploidy) at an increased rate compared with normal cells. Stepwise accumulation of mutations leads to progression from normal colon to adenoma to cancer. The most commonly mutated gene in this pathway is the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, a multifunctional tumor suppressor gene. Deregulation caused by mutations in APC is implicated in the development and spread of colon cancer. Germline mutations in the APC gene lead to hereditary familial adenomatous polyposis.

Microsatellites are dozens to hundreds of repetitive nucleotide sequences seen throughout the human genome. The term microsatellite instability refers to the presence of mismatched bases at repeated DNA microsatellites. Microsatellite instability accounts for about 15% of colorectal cancers and is characterized by defective DNA mismatch repair, leading to multiple mutations, adenomas, and cancer. Defective mismatch repair can occur if there is a germline mutation in one of the mismatch repair genes in Lynch syndrome (including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) or in the epithelial cell adhesion molecule gene (EPCAM), or as a result of sporadic methylation of the MLH1 promoter.

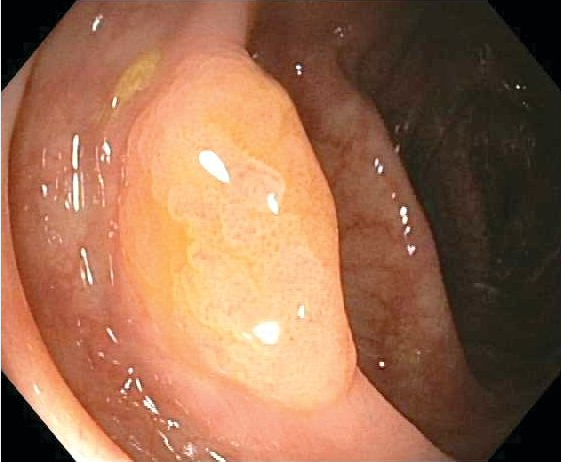

A more recently described mechanism involves hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and the development of serrated polyps and cancer. Serrated polyps are a heterogeneous group of lesions classified by their saw-toothed appearance on histology. Serrated polyps are often found in the proximal colon and may be flat and difficult to distinguish from normal mucosa (Figure 25). Hyperplastic polyps that are benign also develop through this mechanism. Interval colon cancers, which are defined as cancers that develop after a negative colonoscopy and before the next recommended screening colonoscopy, most commonly develop through the serrated neoplasia mechanism. A hereditary condition called serrated polyposis syndrome has been described, but its genetic basis has not been elucidated.

A serrated polyp in the ascending colon, showing flat morphology that can make these polyps difficult to identify on colonoscopy.

A serrated polyp in the ascending colon, showing flat morphology that can make these polyps difficult to identify on colonoscopy.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors have been established for colorectal cancer. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age (50 years and older), male sex, Black race, and a personal or family history of colon adenomas or colorectal cancer. The risk doubles with a family history of colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative.

Long-standing (≥8 years) colonic inflammatory bowel disease (both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis) is associated with about a 2.7-fold increased risk and is dependent on the severity and extent of bowel involvement. Patients with ureterocolic anastomoses after extensive bladder surgeries and adult survivors of childhood malignancy who received abdominal radiation are also at increased risk for colorectal cancer.

Modifiable risk factors associated with increased risk include diets high in red and processed meat; low intake of fruits, vegetables, fiber, and dairy; use of alcohol and tobacco; type 2 diabetes mellitus; sedentary lifestyle; and obesity.

Chemoprevention

Substantial epidemiological and experimental data show that aspirin use prevents colorectal cancer. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updated their guidelines in 2015 to include the use of low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) for preventing colorectal cancer and cardiovascular disease in individuals aged 50 to 59 years who are at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Aspirin use is associated with a 30% decreased risk for colorectal cancer based on cohort and case-control studies. However, randomized controlled trials have not shown a benefit of aspirin in prevention of colorectal cancer. Randomized controlled trials have shown that aspirin decreases the risk for recurrent adenomas.

Studies of other NSAIDs for prevention of colon cancer and adenomas have also yielded positive results; however, benefits of aspirin and other NSAIDs must be weighed against harms, most notably gastrointestinal bleeding.

Some evidence suggests that selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors prevent recurrent adenomas and decrease the incidence of advanced lesions; however, the associated increased cardiovascular risk confounds a recommendation of their use for chemoprevention.

Screening

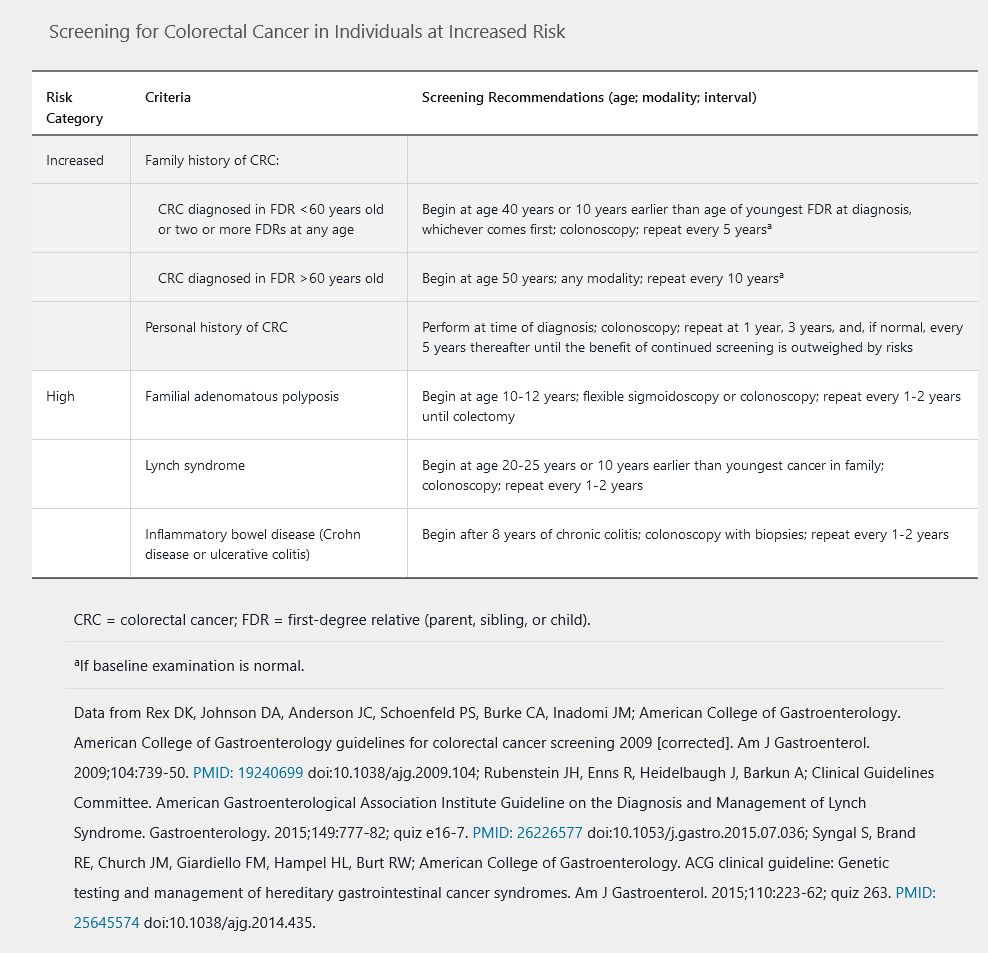

Screening strategies for individuals at increased risk for colorectal cancer are described in Table 23.

Key quality indicators for screening colonoscopy are adequate bowel preparation, preparation sufficient to identify polyps 6 mm in size or larger, visualization of the entire colon to the cecum, and longer duration of colonoscopy.

Because adenomas are an intermediary step in the progression from normal colonic mucosa to colon cancer, the identification and management of polyps is critical. Adenomas can be found throughout the colon. They are classified based on morphology, histology, and degree of dysplasia (Table 24). Adenomas with any degree of villous histology or high-grade dysplasia have greater malignant potential. Risk is also substantially increased in polyps larger than 1 cm in size. The progression of adenoma to carcinoma takes approximately 8 to 10 years.

Clinical Presentation

Colorectal cancer may be asymptomatic, or it may present with iron deficiency anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, altered bowel habits, abdominal pain, colonic obstruction, and weight loss in more advanced cases.

Diagnosis and Staging

The diagnosis of colorectal cancer is usually made by colonoscopy with biopsy. Staging is based on tumor size and extent of invasion into local tissues, lymph node involvement, and evidence of metastasis (TNM system). Cross-sectional imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is used for staging in the initial evaluation after diagnosis. Management of colon cancer depends on stage, evidence of microsatellite instability, and presence of specific mutations, including KRAS/NRAS and BRAF.

For treatment of colorectal cancer, see MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology.

Favorable characteristics include stage 1 to 2, lack of angiolymphatic involvement, and negative margins after polyp removal. Endoscopic resection of polyps is curative in some cases. Malignant sessile or flat polyps are associated with higher risk for recurrence and local or distant spread.

Surveillance

Surveillance for colorectal cancer after screening or polypectomy is based on findings on the baseline examination (Table 25).

A 1-year surveillance is indicated in patients with more than 10 adenomas found on colonoscopy, those with a diagnosed polyposis syndrome, or those with Lynch syndrome. Lynch syndrome is the term used to describe patients who meet the Amsterdam II criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and have an identified germline mutation in one of the four mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) or the epithelial cell adhesion molecule gene (EPCAM).

A 3-year surveillance interval is recommended for patients who have three or more adenomas (or sessile serrated polyps) found on baseline colonoscopy, one adenoma larger than 10 mm in size, or an adenoma with any degree of villous or high-grade dysplasia.

A surveillance interval of 5 years is recommended for patients with two or fewer adenomas (or sessile serrated polyps) found on baseline colonoscopy and for patients with a first-degree relative with colon cancer diagnosed at an age younger than 60 years. Sessile serrated polyps are more frequently found in the proximal colon and may be difficult to detect on colonoscopy due to their flat appearance. Like tubular adenomas, surveillance colonoscopy is based on size and presence of dysplasia.

Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Syndromes

Lynch Syndrome

Lynch syndrome is characterized by germline mutations in the mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) or the epithelial cell adhesion molecule gene (EPCAM), leading to an increased risk for neoplasia of the colon and other organs. Another name for this syndrome, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is no longer used because the syndrome is associated with colorectal polyps as well as extracolonic cancers. The syndrome follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and new mutations are rare.

Individuals with Lynch syndrome are at increased risk for colorectal and endometrial cancers (most common), as well as other cancers, including tumors of the stomach, ovary, hepatobiliary and urinary tracts, small bowel, brain, and pancreas, and sebaceous skin adenoma or cancer.

In persons with Lynch syndrome, the lifetime risk for colorectal cancer depends on the location of the gene mutation, and the risk can be as high as 50% to 80%. Colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome is more likely to occur in the proximal colon and can display characteristic pathological features, such as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and medullary growth pattern. Colorectal tumors in Lynch syndrome result from microsatellite instability that can be assessed using polymerase chain reaction or immunohistochemistry (see Pathogenesis). All colorectal cancers should be screened for Lynch-syndrome genetic mutations or microsatellite instability.

Clinical criteria to evaluate for Lynch syndrome include the Amsterdam and Bethesda criteria, as well as newer models such as the PREdiction Model for gene Mutations 5 (PREMM5). The Amsterdam II criteria follow the “3-2-1-1-0 rule,” which states that a diagnosis is warranted if all of the following criteria are met:

- Three family members are affected with a Lynch syndrome–associated cancer

- Two successive generations are affected

- One affected family member is a first-degree relative of the other two affected family members

- One of the cancers was diagnosed before age 50 years

- A familial polyposis syndrome has been ruled out

- Tumors have been verified histologically

These criteria are specific but not sensitive for the diagnosis of Lynch syndrome. The Bethesda criteria have good sensitivity but poor specificity. Genetic counseling and testing should be offered to patients with a personal and/or family history consistent with Lynch syndrome, as well as patients whose tumor shows evidence of microsatellite instability or loss of mismatch repair protein expression. When a mutation is identified in a family, testing of first-degree relatives should be performed and surveillance instituted.

Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with Lynch syndrome should begin at age 20 to 25 years (or 2-5 years before the age of diagnosis of the earliest cancer in the family). Screening should be done by colonoscopy and repeated every 1 to 2 years. Risk-reducing total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be considered starting at age 40 to 45 years after childbearing is completed in women who carry Lynch syndrome mutations.

Screening with upper endoscopy for stomach and small-bowel cancers can be considered starting at age 30 to 35 years and repeated every 2 to 5 years. Testing for Helicobacter pylori is also recommended in patients at risk for or with Lynch syndrome.

Adenomatous Polyposis Syndromes

Syndromes that predispose to multiple adenomatous polyps in the colon include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), MutYH-associated polyposis (MAP), and polymerase proofreading-associated polyposis (PPAP).

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

FAP is an inherited disorder characterized by multiple (usually more than 100) adenomatous colon polyps. FAP is caused by germline mutations in the APC gene that are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, although de novo mutations occur in about 25% of cases. Adenomas in classic FAP are more numerous in the distal colon than in the proximal colon. Adenoma and cancer develop in 100% of classic FAP cases if surgery is not performed. The average age of colorectal cancer onset is 39 years, with a risk of 93% by age 50 years. An attenuated form of FAP (AFAP) causes fewer polyps (<100 synchronous polyps) with more proximal colonic distribution. The risk for colon cancer in patients with AFAP is about 70% by age 80 years, with an average age of onset of 58 years.

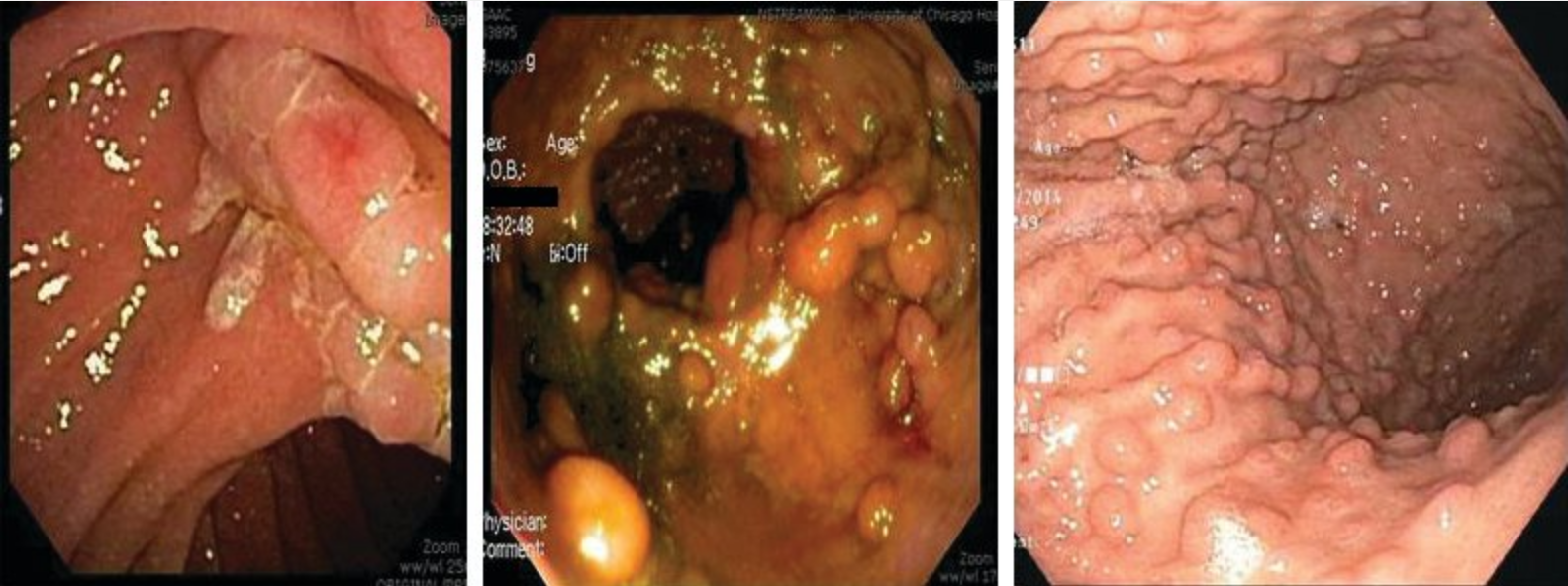

Both FAP and AFAP are associated with extracolonic intestinal manifestations (Figure 26). Duodenal adenomas require surveillance because the lifetime risk for duodenal adenocarcinoma is estimated at 4%. Fundic gland polyps of the stomach do not have malignant potential but can mask gastric adenomas and cancer. Risk for gastric cancer is estimated at less than 1%. Risk for desmoid tumors is increased, especially after surgery to remove the colon. Risk for papillary thyroid cancer is also increased, especially in women. Nonmalignant findings include extra teeth, cysts, osteomas, and congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigmented epithelium.

Intestinal features of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Patients with FAP can develop polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Adenomatous polyps always develop in the colon. Duodenal adenomas can also develop in patients with FAP, especially involving the ampulla of Vater. Regular upper endoscopic surveillance is indicated to remove polyps larger than 10 mm (left). If a patient with FAP has had surgery and has an ileorectal anastomosis, that patient must continue to be surveyed regularly because rectal polyps can develop in the remaining rectum (center). Numerous fundic gland polyps of the stomach can develop in FAP (right).

Screening in classic FAP mutation carriers should begin at age 10 to 12 years with sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy and repeated every 1 to 2 years. Screening in patients with AFAP can be delayed until age 20 to 25 years and should be performed with colonoscopy. For individuals with FAP and AFAP, screening with upper endoscopy should begin at age 25 to 30 years and include visualization of the papilla with a duodenoscope. Fundic gland polyps in the stomach should be randomly sampled. Surveillance of the upper gastrointestinal tract is determined by findings in the duodenum. Annual thyroid ultrasound is also recommended.

Colectomy is the treatment of choice for classic FAP and may be pursued in patients with AFAP. Absolute indications for surgery include cancer and significant symptoms such as rectal bleeding. Relative indications include multiple adenomas greater than 6 mm size, increase in number of polyps, an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, and multiple diminutive polyps, which can prevent identification of adenomas. The type of surgery depends on the polyp burden in the rectum; total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis is indicated for patients with a small rectal polyp burden, and total proctocolectomy with ileo-pouch anastomosis is indicated for patients with a large rectal polyp burden. Postsurgical surveillance is yearly sigmoidoscopy for those with an intact rectum and ileoscopy every 2 years for patients with an ileostomy.

MutYH-Associated Polyposis

MAP is an inherited syndrome characterized by fewer adenomas than classic FAP. MAP is caused by mutations in the MutYH gene, a component of base excision repair. MAP is a recessive condition in which an affected patient has inherited two mutated copies from their parents. Most patients have between 20 and 99 adenomatous colon polyps. Some individuals can develop cancer with only a few or no synchronous adenomas. Mean age of cancer onset is about 52 years. In addition, other polyp types can be encountered in patients with MAP, including serrated and hyperplastic polyps. Duodenal cancer risk in MAP is estimated at 4% and surveillance with upper endoscopy is similar to that indicated in patients with FAP. Surgical management of the colon is similar to that of FAP.

Polymerase Proofreading-Associated Polyposis

This more recently described syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. PPAP appears to have features of both FAP and Lynch syndrome and is caused by mutations in polymerase proofreading genes POLE and POLD1. Endometrial cancer has been described in this syndrome, and tumor testing has been reported to show microsatellite instability. Management guidelines have not been established for PPAP, but management of colonic polyps follows similar principles as for other adenomatous polyp syndromes.

Hamartomatous Polyposis Syndromes

Hamartomas refer to polyps caused by overgrowth of normal tissue. There are three primary syndromes associated with hamartomas in the gastrointestinal tract: juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), and PTEN hamartoma syndrome, also known as Cowden syndrome.

Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome

JPS is caused by mutations in the BMPR1A and SMAD4 genes. It has an incidence of approximately 1 in 130,000 live births. Multiple juvenile polyps (>5 polyps) are found in the colon (98%), stomach (14%), and small bowel (14%) of patients with JPS (Figure 27). Sporadic juvenile polyps can be found in up to 1% of children and are not considered syndromic. The average age of patients at the time JPS is diagnosed is 18.5 years, and rectal bleeding is the most common symptom. Patients with JPS are at increased risk for colon, stomach, and small-bowel cancer. Individuals with mutations in the SMAD4 gene can also have hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

PJS is caused by mutations in the STK11 gene. Its incidence is approximately 1 in 200,000 live births. PJS hamartomas are found primarily in the small bowel but can also develop in the stomach and colon (Figure 28). PJS is also characterized by hyperpigmented mucocutaneous macules on the lips and buccal mucosa (Figure 29).

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is associated with multiple hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract and distinctive mucocutaneous pigmentations. The pigmented lesions occur most commonly on the lips and perioral region but can also occur on the nose, perianal area, and genitals.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is associated with multiple hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract and distinctive mucocutaneous pigmentations. The pigmented lesions occur most commonly on the lips and perioral region but can also occur on the nose, perianal area, and genitals.

Small bowel hamartomas develop at a young age in patients with PJS, and may present with intussusception, obstruction and bleeding. Patients with PJS have increased risk for cancer in the colon, stomach, small bowel, breast, ovary, cervix, uterus, testicles, lung, and pancreas.

PTEN Hamartoma Syndrome

Also known as Cowden syndrome, this syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the tumor suppressor gene PTEN. It is characterized by gastrointestinal hamartomas associated with a number of cancers, such as breast, thyroid, kidney, and colon cancer, as well as macrocephaly, esophageal glycogenic acanthosis, and dermatological manifestations. Colorectal cancer prevalence is estimated at 9% to 18%.

Serrated Polyposis Syndrome

Serrated polyposis syndrome is characterized by numerous serrated polyps in the colon. The definition is based on having any of the following:

- Five or more serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon, with two or more greater than 10 mm in size

- Any number of serrated polyps in patients with first-degree relatives with serrated polyposis syndrome

- More than 20 serrated polyps throughout the colon

Estimates suggest that the prevalence of serrated polyposis syndrome is between 0.3% and 0.6%. Risk for colon cancer in patients with this syndrome is increased, and smoking appears to be a risk factor. Colonoscopy is recommended every 1 to 3 years with removal of all polyps greater than 5 mm in size. Surgery may be considered if the polyps cannot be managed endoscopically. No extracolonic manifestations have been noted in serrated polyposis syndrome. The genetic basis of the syndrome is unknown.