Cognitive Impairment

- related: Neurology

- tags: #neurology

Definition

Cognitive impairment is the progressive loss of cognitive function in at least one major category: memory, language, executive function, visuospatial function, or behavior. When the level of cognitive impairment is progressive, involves more than one cognitive function, and results in a loss of independent function, it is considered a dementia syndrome. Fixed cognitive disorders occurring after a brain lesion, such as stroke or traumatic brain injury, are excluded from the dementia category.

General Approach to the Patient With Cognitive Impairment

Dementia syndromes are chronic disorders that typically develop over years; intervention when dementia is well established is likely too late to have a meaningful effect on the disorder. Although definitive evidence that earlier diagnosis improves patient outcomes is lacking, screening for dementia has become the subject of increased interest. At this time, however, there are no accepted standards for dementia screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not endorse screening, but the Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics recommends that some form (objective or subjective) of cognitive screening be performed annually in patients age 70 and older.

In the absence of screening, certain signs and behaviors may raise clinical suspicion of a cognitive disorder and provoke evaluation in a primary care setting. Examples include concerns expressed by family members or caregivers, frequent missed (or late arrival to) appointments, changes in medication adherence, unexplained weight loss, presence of a partner or family member at patient appointments when the patient previously was seen alone, and withdrawal from previously enjoyed hobbies.

Many bedside cognitive evaluation tools have demonstrated adequate sensitivity and specificity for detecting cognitive impairment in population-based settings. The most common are the Mini–Mental State Examination, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Ascertain Dementia 8 questionnaire, the Mini-Cog test, and the five-word memory test. Each of these tests can be performed in less than 5 to 10 minutes; no compelling data support the superiority of one test over another. These tests are increasingly used to justify billing and medication-authorization decisions by insurers.

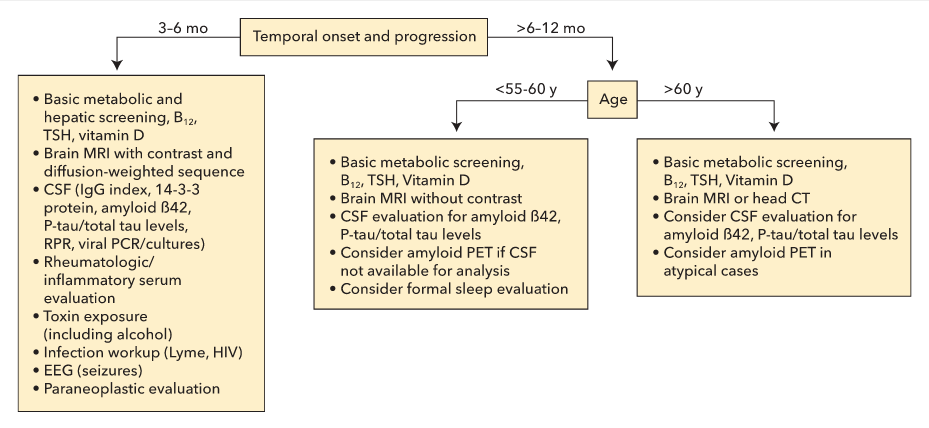

After cognitive impairment is diagnosed, determining whether it is reversible or nonreversible is imperative in the initial evaluation of the patient. Essential elements in this determination are the time course of symptom onset and progression, the principal cognitive domain or function affected and its functional impact, and other associated neurologic and nonneurologic symptoms (Figure 15). Access to a reliable informant familiar with the patient's condition is critical in the evaluation of the cognitive disorder. The signs and symptoms of a cognitive disorder also may have an anatomic correlate that can be used to help guide the diagnosis and treatment. For example, a progressive loss of language function localizes to a different anatomic location than does a primary memory problem, which may be helpful in determining the underlying cause of the impaired function. The age of the patient also is an important consideration; for example, both atypical presentations of typical dementia syndroes and nonneurodegenerative causes are more common in younger patients.

Diagnostic test consideration in patient with a dementia syndrome. CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; EEG = electroencephalography; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; PET = positron emission tomography; P-tau = phosphorylated tau; RPR = rapid plasma reagin test; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

For a slowly progressive dementia syndrome in an older patient, the American Neurological Association recommends that a minimum evaluation include the following elements:

- General neurologic examination, including a cognitive screening evaluation

- Evaluation for depression, sleep disorders, alcohol use, and family history of dementia

- Detailed medication review

- Serum chemistries, including plasma glucose level

- Complete blood count

- Determination of vitamin B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels

- A rapid plasmin reagent test to evaluate for syphilis in high-risk populations

- Basic neuroimaging (MRI or CT without contrast)

In the older population, increasing evidence also suggests that chronic vitamin D deficiency increases the odds of developing dementia. Therefore, measuring serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels is a recommended part of the evaluation. When patient age, disease progression, or other associated symptoms raise the possibility of a more uncommon type of dementia, additional diagnostic tests and early referral to a specialist should be considered (see Figure 15).

Several more specialized testing modalities are available. These tests should be reserved for patients with an uncertain diagnosis (for example, to distinguish dementia from pseudodementia), for an atypical progression of a previously established diagnosis (such as an excessively slow course of Alzheimer disease), and for discriminating between two types of dementia with overlapping features (such as the detection of Alzheimer disease–specific biomarkers). These tests, if required, are typically ordered by a dementia specialist.

These specialized diagnostic tests fall into two categories:

- Disease-specific tests: measurement cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the tau protein and 42-residue form of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ42) in patients with Alzheimer disease; prion-specific PET (using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose [FDG]) to detect amyloid plaques in Alzheimer disease; and dopamine-transporter single-photon emission CT (SPECT) in patients with cognitive impairment and symptoms of parkinsonism (see Movement Disorders chapter).

- Disease-nonspecific tests: FDG-PET to measure cerebral metabolism; SPECT measuring cerebral blood flow to detect disease-relevant patterns; MRI to detect and measure brain atrophy; and CSF analysis to detect inflammation, infection, neuronal injury, and paraneoplastic antibodies.

Dementias

Dementia syndromes can be divided into neurodegenerative and nonneurodegenerative categories. Neurodegenerative dementias involve a progressive loss of the underlying brain tissue related to a pathologically identifiable pattern of protein accumulation. Distinction between syndromes typically can be made through careful consideration of the temporal onset and progression, the core cognitive dysfunction, and the associated neurologic and nonneurologic signs and symptoms.

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Mild Cognitive Impairment

Within the framework of early detection of dementia, the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a commonly used measure to identify patients with clear symptoms of cognitive decline who do not meet criteria for dementia. The formal criteria for MCI are a subjective report (from either the patient or a witness) of a decline in cognitive abilities with relative preservation of day-to-day function and evidence of cognitive impairment on cognitive testing.

The annual risk of MCI progressing to dementia ranges from 5% to 15%, but a significant percentage of patients (as many as 20%) have normal findings on subsequent examinations. The risk of progression depends on the number of cognitive domains affected and the presence of markers of an underlying neurodegenerative process. Because of wide variability in the risk of progression, steps should be taken to confirm the underlying cause of the symptoms. The initial diagnostic approach should follow that used in patients with dementia, and specialized testing (CSF analysis, PET) is not recommended unless a specific dementia syndrome is suspected. Abnormalities on these studies may help more accurately predict the risk of progression.

Treatment

No medications are currently approved for the treatment of MCI, and no medications or dietary agents have been shown to prevent progression to dementia. The Lancet Commission 2020 supports addressing modifiable risk factors for dementia prevention, intervention, and care, including excessive alcohol use, head injury, air pollution, less education, hypertension, hearing loss, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, and limited social contact. The American Academy of Neurology recommends that cognitively impairing medications should be discontinued when possible and behavioral symptoms treated. Clinicians should also recommend regular exercise and may recommend cognitive exercises, but there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any individual cognitive strategy. Use of vitamins B and E, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and multicomplex supplementation is not recommended.

Alzheimer Disease

The most common memory-predominant dementia is Alzheimer disease, which likely accounts for 60% to 80% of neurodegenerative dementias. Age is the greatest risk factor; after age 65 years, the prevalence doubles every 5 years. A second major risk factor is the presence of one or two copies of the apolipoprotein-E ε4 (APOE ε4) allele. Additional risk factors include a family history of dementia, female sex, history of stroke, and (to a lesser extent) head injury and cardiovascular disease. Evidence suggests that education, regular exercise, a Mediterranean diet, and cognitively stimulating leisure activities provide protection against developing Alzheimer disease.

The pathophysiology of Alzheimer disease is unclear. The principal pathologic findings, however, include brain volume loss, extracellular fibrillar Aβ plaques, and intracellular neurofibrillary tau tangles. Notably, the development of Aβ pathologic features begins as early as 15 to 20 years before symptom onset.

The typical presentation of Alzheimer disease is that of an insidious worsening of memory, language, and visuospatial abilities. Manifestations include forgetfulness (misplacing objects, missing appointments, frequently repeating questions or statements, missing bill payments), word-finding difficulties, hesitation in speech, and navigational problems (difficulty with directions while driving, even to familiar places, or disorientation in unfamiliar places). These symptoms are often followed by problems with executive function (organizational abilities and multitasking), problems with calculations (managing finances), and behavioral and mood symptoms (apathy, depression, anxiety, irritability, and agitation). In most instances, the patient's insight remains well preserved early in the disease. As the disease progresses, behavioral symptoms, including delusions, become more common. In contrast to dementia with Lewy bodies, however, hallucinations are rare. Motor symptoms and gait problems also do not typically occur until well into the moderate stages of the disease when daily function is significantly impaired. Early hallucinations and motor problems suggest the presence of a disorder other than Alzheimer disease (Table 27).

In younger-onset Alzheimer disease, nonmemory symptoms are more frequently the predominant pattern and include language-predominant, executive function–predominant (impaired organizational abilities, disorganized thoughts, poor attention span), and visual/perceptive–predominant (impaired depth perception, navigational problems, problems with coordination) forms. Memory impairment is initially minimal.

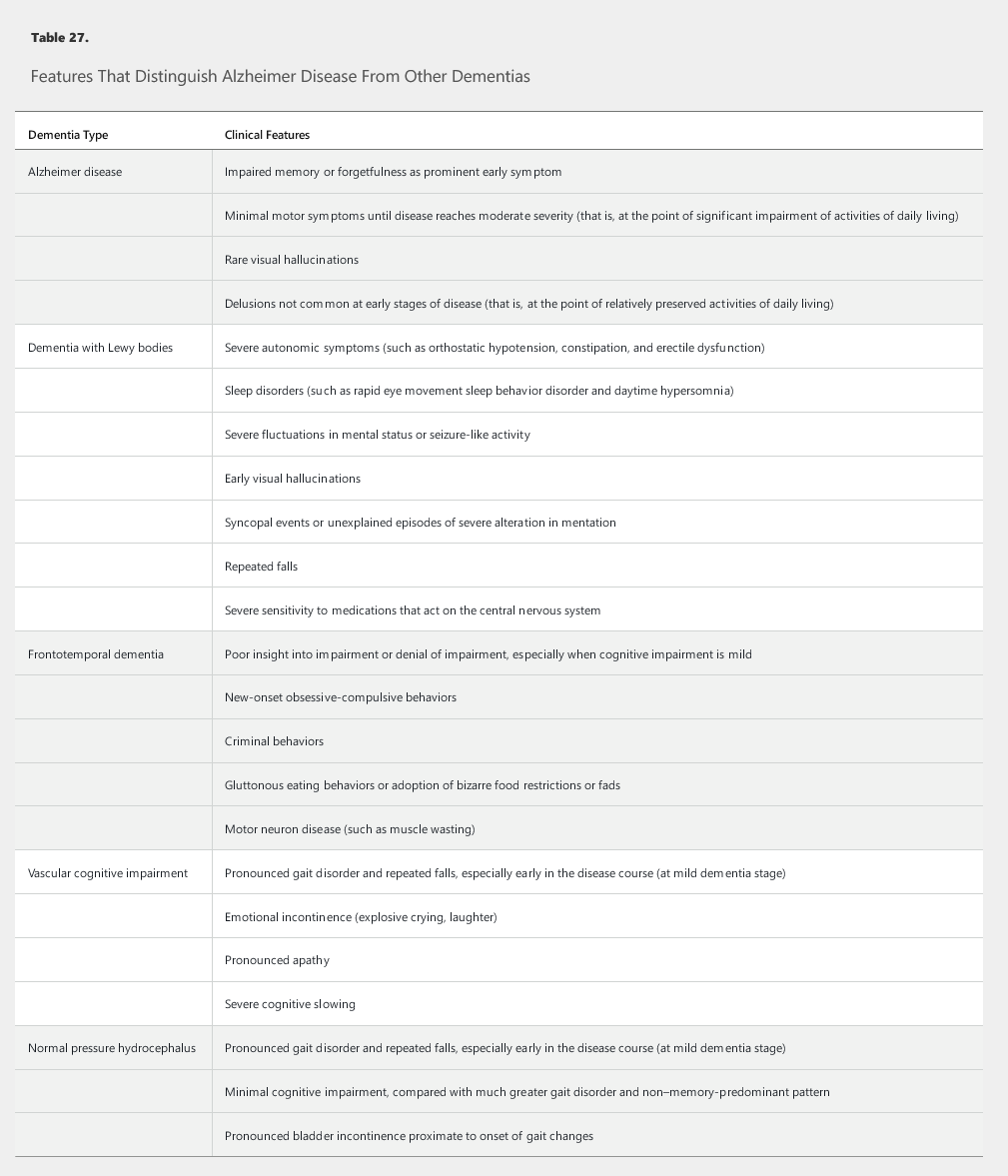

Evaluation

MRI of the brain supports the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease when it shows evidence of decreased volume of the hippocampi (Figure 16), although this is a nonspecific finding. When seen in MCI, decreased hippocampal volume predicts a higher likelihood of progression to Alzheimer disease. When the MRI is normal and the diagnosis is in question or a non–Alzheimer disease process is being considered, functional brain scans (FDG-PET or perfusion SPECT) can be used to look for the Alzheimer disease pattern of decreased brain function in the bilateral parietal and temporal regions.

MRI findings showing bilateral hippocampal atrophy (arrows), which is a typical feature of Alzheimer disease, and diffuse cortical atrophy, which is recognized widening of the sulci and enlargement of the ventricles.

MRI findings showing bilateral hippocampal atrophy (arrows), which is a typical feature of Alzheimer disease, and diffuse cortical atrophy, which is recognized widening of the sulci and enlargement of the ventricles.

In situations involving an uncertain diagnosis or a younger patient, Alzheimer disease–specific biomarkers also can be sought. A CSF test for Alzheimer disease biomarkers is FDA approved and frequently covered by insurers. In the presence of dementia, a pattern of decreased Aβ42 and increased tau and phosphorylated tau levels is highly specific for Alzheimer disease; conversely, a normal Aβ42 level has a high negative-predictive probability for Alzheimer disease. Three Aβ plaque PET scans are FDA approved for detecting these findings, but their role in the diagnosis of dementia is unclear. Trials are currently underway that may further delineate the role of amyloid scanning in the evaluation of dementia and Alzheimer disease.

Treatment

The nonpharmacologic management of Alzheimer disease includes aggressively treating possible factors contributing to disease progression, such as sleep disorders (including obstructive sleep apnea) and cardiovascular disease; risk factors for cardiovascular disease also should be addressed. Adhering to an exercise program should be encouraged. Dietary recommendations for slowing cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease or MCI remain uncertain. Given the links between cardiovascular disease risk factors and Alzheimer disease, it is generally recommended that affected patients follow a “heart-healthy” diet (a diet rich in whole grains, fruits, and vegetables and low in simple carbohydrates, polyunsaturated or trans-fatty acids, nitrates, and alcohol). The use of nutraceuticals (supplements enriched with nutrient precursors of many substrates for healthy brain function) has shown benefit in some, but not all, trials and remains controversial. If homocysteine levels are elevated, folic acid supplementation is recommended. There is moderate evidence showing a benefit of vitamin E (200-400 U/d) for moderate Alzheimer disease but not for MCI. No conclusive data have shown a link between statin use and development of Alzheimer disease, and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have shown no clear benefit or harm to cognition from statins. However, given the numerous case reports of cognitive decline after statin therapy, the FDA has issued a warning about possible worsening cognition after initiation of some statins. Clinicians should consider discontinuing statin therapy if there is a clear temporal link between starting this therapy and significant cognitive decline.

The acetylcholinesterase inhibitors donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine are approved for treating mild to moderate dementia in patients with Alzheimer disease and have demonstrated modest benefits in cognitive performance without clear improvements in daily functioning. These three drugs have differences in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics but appear equally efficacious. Because of their possible adverse effects on conduction, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors should be used with caution or avoided in patients with bradycardia or other conduction abnormalities. A transdermal form of rivastigmine is available but should be used only after intolerance of oral forms has been established. The most common adverse effects are gastrointestinal issues, which result in discontinuation of the medication in nearly 20% of patients. Additional adverse effects include syncope, agitation, nocturnal cramps, and vivid dreams. Donepezil should be used with caution in patients with a history of seizures.

The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine is approved for moderate to severe dementia in patients with Alzheimer disease associated with significant functional impairment and is not associated with adverse cardiovascular effects. It has no established benefit in mild dementia. Some evidence suggests that combining an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist provides a synergistic benefit, but only when the latter is added at the moderate stage of dementia.

Antibodies targeting Aβ plaques represent another potential means of treatment and are the subject of current study. Preliminary clinical trials have shown that the antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer disease accompanied by a slowing of clinical decline.

Frontotemporal Dementia

The frontotemporal dementias (FTDs), which comprise language-variant and behavioral-variant types, are the second most common cause of neurodegenerative dementia in patients younger than 65 years. The language-variant FTDs consist of the primary progressive aphasias and are discussed separately in Language-Predominant Dementias. In behavioral-variant FTD, there is a slight male predominance and shorter disease duration than in Alzheimer disease. As many as 10% of patients with behavior-variant FTD have a family history consistent with an autosomal-dominant inheritance of dementia, and as many as 30% to 40% have evidence of a family history of a dementia. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis occurs in as many as 20% to 30% of patients with behavior-variant FTD and generally portends a much more rapid progression than other forms of FTD. The pathology underlying FTD involves neurofibrillary tau tangles or transactive-response DNA-binding protein 43 inclusions.

The most prominent feature of behavioral-variant FTD is an alteration in personality and behavior that typically develops years before the onset of cognitive impairment. A clue to the diagnosis early in the disease is discordance between normal or near-normal performance on objective cognitive testing and a significant degree of functional impairment. Because these behaviors often manifest as obsessive-compulsive tendencies, impulsivity, apathy, and impaired judgment, patients with this disorder are often misdiagnosed as having bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression. Other common symptoms are emotional coldness, disinhibition, excessive spending, and excessive eating, particularly of high-calorie foods. These behaviors occasionally result in legal troubles. Unlike patients with Alzheimer disease, those with behavioral-variant FTD often have poor insight into their disease.

Diagnostic criteria have been proposed, with the diagnosis of behavioral-variant FTD being established when three of the following six criteria are met: early behavioral disinhibition, early apathy or inertia, early loss of sympathy or empathy, perseverative or compulsive behaviors, hyperorality and dietary changes, and neuropsychological deficits in executive function with memory and visuospatial sparing.

Evaluation

Because cognitive testing results can be normal early in the disease course, Alzheimer disease screening tools are not helpful for evaluating FTD. When this diagnosis is suspected, detailed cognitive testing by a neuropsychologist is indicated.

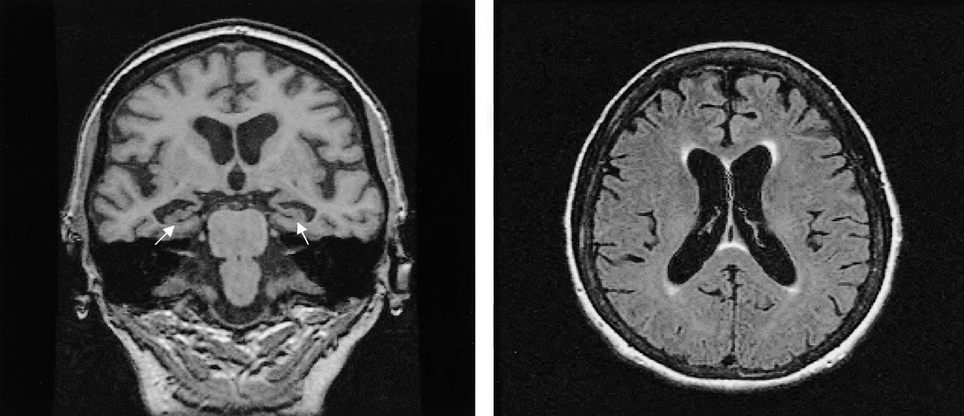

Because structural lesions of the frontal lobes can result in a syndrome similar to behavioral-variant FTD, neuroimaging with MRI or CT is mandatory. Additionally, many patients with behavioral-variant FTD have frontotemporal lobe atrophy visible on imaging (Figure 17). If the MRI is normal, a functional brain scan (FDG-PET or perfusion SPECT) may show a pattern of prominent frontal lobe abnormalities.

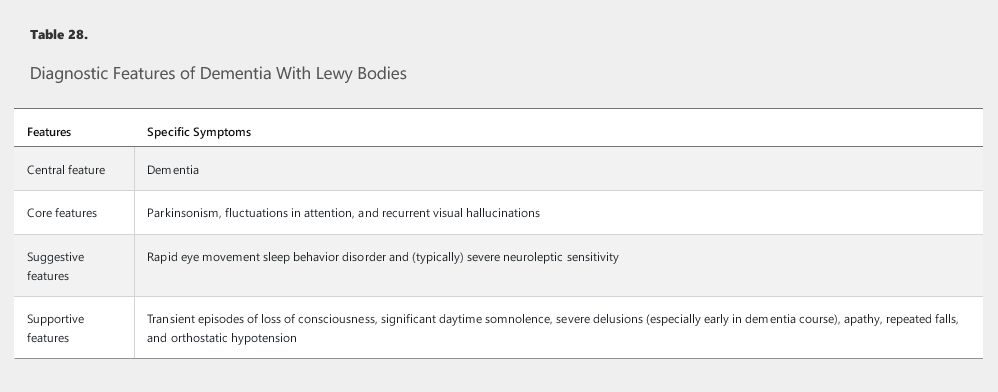

Brain MRI findings showing changes associated with frontotemporal dementia, including bilateral hippocampal atrophy (arrows) and more severe temporal and frontal cortical atrophy.

Brain MRI findings showing changes associated with frontotemporal dementia, including bilateral hippocampal atrophy (arrows) and more severe temporal and frontal cortical atrophy.

A CSF evaluation also can be helpful in distinguishing FTD from Alzheimer disease because the Aβ42 level is typically depressed in Alzheimer disease but normal in FTD.

Finally, because of the association with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, all patients with a diagnosis of behavioral-variant FTD should be monitored closely for muscle weakness, cramping, or fasciculations.

Treatment

There are currently no approved therapies to treat behavioral-variant FTD, and clinical trials testing the effectiveness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have shown no benefit (and, in the case of memantine, possible detriment). Treatment is symptomatic and can involve collaboration with a psychiatrist.

This patient should be given the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram to control her obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Early changes in social behavior and personality are the defining characteristics of behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Apathy, diminished interest, loss of empathy, lack of initiative, increased emotionality, disinhibition, euphoria, impulsivity, changes in eating behaviors, hyperorality, and compulsiveness are the most common symptoms reported by families. Other changes include irritability, aggression, verbal abuse, hypomania, and restlessness. The treatment of behavioral-variant FTD is symptom based and should target the most troubling manifestations of the disorder. This patient's obsessive-compulsive tendencies not only have had embarrassing consequences but have resulted in a confrontation with family members. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as citalopram, have the potential to alleviate these symptoms. Tricyclic antidepressants may also have this effect.

Atypical antipsychotic agents (such as olanzapine) can be effective in treating agitation, aggression, delusions, and hallucinations. However, these drugs are not FDA approved for this clinical indication and have an associated black-box warning due to increased cerebrovascular events and mortality rates in patients with dementia.

Language-Predominant Dementias

The primary progressive aphasias (PPA) are a group of neurodegenerative dementia syndromes in which a progressive impairment in language is the principal cognitive deficit and cause of functional impairment. PPAs can be subdivided into nonfluent and fluent (semantic) variants. In nonfluent PPA, patients predominantly have problems with language production; those with fluent PPA largely have problems with comprehension. Although language decline is common in many dementia syndromes, in PPA it is the symptom noted first, and language is often the only cognitive domain affected for years before the development of additional cognitive deterioration. Pathologically, the PPAs are related to FTD and Alzheimer disease but typically occur at a younger age. Because of the relationship to FTD, the fluent (semantic) variant of PPA often has significantly more behavioral symptoms than the nonfluent variant.

Evaluation

The language components of the cognitive screening evaluation are disproportionately affected in language-predominant dementias. Sentence or phrase repetition, timed word production, and object naming are all impaired. Because most cognitive tests are language based, patients with PPA often perform worse than expected given their level of day-to-day functioning (the opposite of what is seen in behavioral-variant FTD).

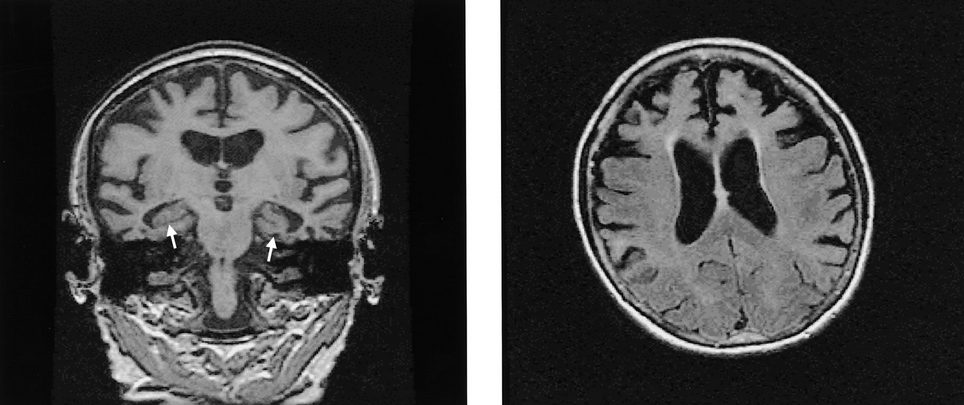

Structural imaging can be very helpful; attention should be paid to asymmetric involvement of the left temporal lobe, which controls language in most patients (Figure 18). Functional brain imaging (FDG-PET or perfusion SPECT) can identify a pattern of asymmetric hemispheric abnormality (left greater than right) in patients with inconclusive brain MRIs.

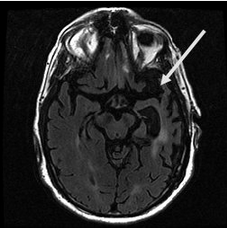

Brain MRI of a 64-year-old woman that shows severe left temporal lobe atrophy (arrow), consistent with fluent primary progressive aphasia.

Brain MRI of a 64-year-old woman that shows severe left temporal lobe atrophy (arrow), consistent with fluent primary progressive aphasia.

As with FTD, CSF evaluation can be helpful in diagnosing a language-predominant dementia if it identifies an Alzheimer disease pattern (decreased Aβ42 with elevated levels of tau and phosphorylated tau), which may help with tailoring treatment.

Treatment

There are no pharmacologic therapies specifically approved for PPA. All affected patients should be assessed by a speech therapist. If language comprehension is an issue, assistive language devices can be helpful.

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is technically a pathologic diagnosis. Because of its relationship with a history of head injuries—most commonly, repeated head trauma—the term also is used clinically. The frontal and temporal lobes are most susceptible to damage from head trauma, and symptoms often reflect damage to these areas. CTE may develop over many years, which makes the diagnosis challenging, particularly when it occurs in patients in their sixties and seventies when the prevalence of other dementias also increases.

A major clinical feature of the disease is the greater frequency of somatic symptoms, particularly headache, that precede the onset of cognitive symptoms. Similarly, the behavioral and mood findings of apathy, irritability, impulsivity, emotional outbursts, and depression often occur before overt cognitive impairment. The cognitive pattern is often one of cognitive slowing and disorganized thought processing, with less involvement of memory and visuospatial function early in the disease course. As the disease progresses, symptoms of mild parkinsonism, such bradykinesia and gait changes, frequently occur.

Evaluation

A history of repeated head trauma is necessary for the diagnosis. Cognitive testing often will demonstrate a pattern of cognitive slowing (problems with timed tasks) as a prominent finding. In patients with more advanced disease, memory impairment may occur. No specific pattern of brain atrophy is seen on structural brain imaging, which can help differentiate CTE from FTD (which is associated with frontal lobe atrophy).

Treatment

No clinical trials comparing various treatments have been performed in CTE. Cholinergic deficits have been identified pathologically, which suggests that acetylcholinesterase inhibitors might be useful. As in behavioral-variant FTD, treatment is often symptom directed and includes Parkinson disease medications for motor symptoms, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and (occasionally) stimulants for severe apathy. Close monitoring for suicidality also should be part of treatment strategy for patients with CTE.

Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Parkinson Disease Dementia

DLB is the second most common neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer disease. α-Synuclein deposits, or Lewy bodies, are the chief pathologic feature of DLB and commonly coexist with pathologic features of Alzheimer disease.

Because Parkinson disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, cognitive symptoms frequently develop at some point in the disease course. When dementia occurs well after the motor symptoms, it is considered Parkinson disease dementia. When dementia and motor symptoms develop within 1 to 2 years of each other, it is classified as dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

The prevalence of DLB significantly increases with age, and this dementia often progresses more rapidly than Alzheimer disease. The clinical diagnosis rests on the key features of dementia, parkinsonian motor features (particularly gait problems and slowness of movements), visual hallucinations, and frequent fluctuations in attention (Table 28). The latter may manifest as acute confusional episodes or brief, focal seizures with alteration of awareness (formerly known as complex partial seizures).

Distinguishing DLB from Alzheimer disease on the basis of cognition alone can be difficult, but other symptoms can help differentiate the two. Delusions and hallucinations are common and frequently occur at the mild stages of DLB. Additionally, significant sleep problems, especially daytime sleepiness, can be a debilitating feature of DLB, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder is much more common.

Making the diagnosis of DLB as early as possible is important because the behavioral problems associated with this condition frequently result in the use of antipsychotic agents. Many patients with DLB are extremely sensitive to neuroleptic medications, particularly first-generation agents, and are at high risk for developing a severe worsening of symptoms resembling neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Evaluation

The evaluation of DLB is similar to that of the other dementia syndromes, and the cognitive impairment is often similar to that of Alzheimer disease. CSF evaluation is often inconclusive in DLB. The best diagnostic tools remain the clinical history and examination.

Treatment

Although not formally approved for DLB, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil) can be effective in treating the cognitive symptoms of the disorder, according to expert opinion. Rivastigmine has been approved for treating Parkinson disease dementia but not DLB; there is no evidence that memantine is beneficial. The treatment of behavioral symptoms is often necessary, but first-generation antipsychotic agents are strongly contraindicated. In the case of severe hypersomnolence, stimulant-type medications can be considered.

Atypical and typical antipsychotic agents have a black-box safety warning when used in patients with underlying dementia. Although not formally approved for DLB, donepezil can be effective in treating the behavioral and cognitive symptoms associated with the disorder; controlled clinical trials, however, remain inconclusive. Because donepezil (or any other medication) has not been shown to be efficacious for DLB in high level, well-conducted trials, its use is based on expert opinion at this time. Nevertheless, donepezil is likely the safest and most efficacious medication for this patient.

Haloperidol is absolutely contraindicated in DLB because of the risk of significant worsening of the dementia syndrome. In addition, the patient is not aggressive at this point and is unlikely to harm himself or others, so antipsychotic agents are unnecessary, as are medications with a strong sedating effect (such as diphenhydramine).

Many patients with dementia with Lewy bodies are extremely sensitive to neuroleptic medications, particularly first-generation agents, and are at high risk for developing a severe worsening of symptoms resembling neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Treatment Approach to Neurobehavioral Symptoms of Dementia

Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia are a common problem in patients with dementia disorders and are among the most common reasons for admission to long-term care facilities. Multidisciplinary care, massage and touch therapy, and music combined with massage and touch therapy were clinically more efficacious than usual care, including pharmacologic care, in treating aggressive and agitated behaviors in patients with dementia, according to a recent systematic review. Nonpharmacologic environmental and behavioral treatments should be emphasized for these patients, although some pharmacologic therapies may improve function and patient safety. Antidepressant agents should be considered the first-line therapy for symptoms related to mood and anxiety. If appropriate, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors also may be tried early in the disease course. Benzodiazepines should be avoided, except in cases of extreme anxiety.

The use of antipsychotic agents to treat behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia should be considered on an individual basis. Strong evidence links use of antipsychotic agents with increased mortality in older persons with dementia. At the same time, there is evidence of benefit for certain antipsychotic agents (such as risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine). If antipsychotic agents are needed, newer-generation medications should be started at low doses with a regimented titration and a plan for regular follow-up evaluation and dose decreases. These drugs are associated with an increased risk of sudden death (likely cardiac), especially in the first 3 to 6 months of taking the medication; this risk should be clearly discussed with families before initiating the therapy and only after all other treatments have been tried. It is also advisable to obtain an electrocardiogram before the first dose to ensure that the patient's QT interval is normal; if the corrected QT interval is prolonged (>450 ms for men and >470 ms for women), antipsychotic agents should not be used.

Nonneurodegenerative Dementias

Two of the most common nonneurodegenerative dementias are normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) and vascular cognitive impairment. Both share the symptoms of prominent gait impairment and a pattern of cognitive slowing with less memory impairment.

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

NPH is characterized by the triad of gait changes, urinary incontinence, and cognitive impairment. Gait impairment, the most prominent feature, is characterized by a wide-based gait, short step length, and often problems with starting ambulation (hesitation).

Evaluation

Gait changes can occur for multiple reasons and in several neurodegenerative diseases, so recognition of the gait pattern specific for NPH is crucial. Similarly, alternative causes for urinary incontinence should be excluded. Cognitive testing typically reveals a pattern of slowing and executive cognitive impairment; some patients may require formal neuropsychological testing.

A brain MRI or CT scan should be obtained because NPH cannot be diagnosed without evidence of ventriculomegaly (Figure 19). Lumbar puncture with high-volume (30-50 mL) CSF removal and determination of opening pressure also is required. A timed gait evaluation should be performed just before CSF removal and within 60 minutes after removal. Objective improvement in gait after CSF removal is an accurate predictor of NPH improvement with shunting.

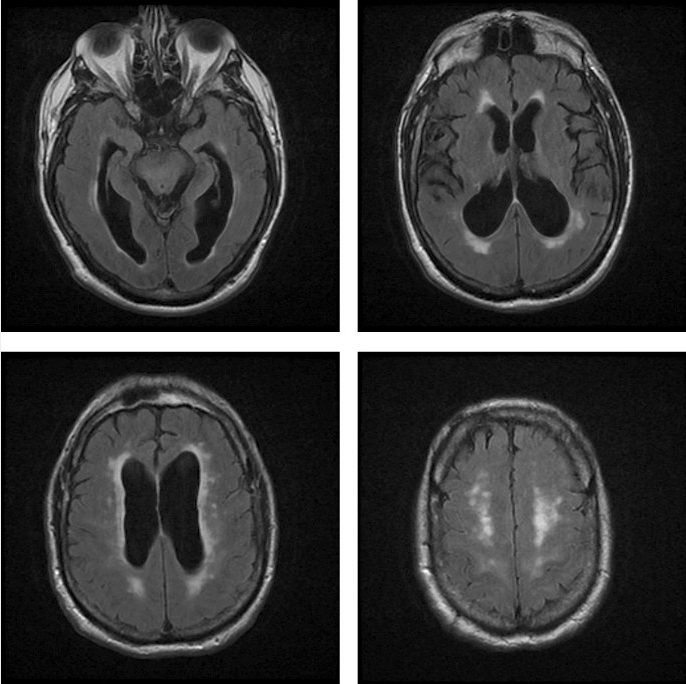

Multiple axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRIs of a 68-year-old man that show ventriculomegaly, little cortical atrophy, and mild periventricular FLAIR hyperintensities, all consistent with normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Multiple axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRIs of a 68-year-old man that show ventriculomegaly, little cortical atrophy, and mild periventricular FLAIR hyperintensities, all consistent with normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Treatment

CSF diversion through a ventriculoperitoneal shunt is the definitive treatment. Gait disturbance is the clinical symptom most amenable to ventricular shunting. The longer cognitive impairment has been present and the more pronounced the memory problem, the less certain is the response to shunting. If response to high-volume CSF removal is uncertain, referral to a neurosurgeon for a lumbar drain can be pursued. In the absence of a clear response to either high-volume CSF removal or lumbar drainage, a permanent ventricular shunt should not be pursued, and another diagnosis should be considered.

Vascular Cognitive Impairment

Vascular cognitive impairment encompasses a category of disorders in which the causal link between cerebrovascular disease and cognitive impairment is strong. In older populations, vascular cognitive impairment is likely second only to Alzheimer disease as the most common primary cause of dementia (but not of neurodegenerative dementia; see earlier discussion of Dementia with Lewy bodies). This disorder may occur concurrently with Alzheimer disease in older patients.

The likelihood of vascular cognitive impairment increases with age and is associated with systemic vascular risk factors and a history of stroke (either clinically diagnosed or based on neuroimaging evidence). Several features distinguish vascular cognitive impairment from Alzheimer disease (see Table 27). Two major signs of vascular cognitive impairment are early gait impairment and pseudobulbar affect (“emotional incontinence”) that can manifest as excessive crying or laughter disproportionate to the context of the situation and is abrupt in onset and discontinuation.

Evaluation

Evaluation of vascular cognitive impairment relies on identification of vascular risk factors and, particularly, previous stroke. Abrupt changes in cognition and a cognitive pattern of disproportionate cognitive slowing compared with memory impairment are often noted.

As with NPH, brain imaging is a critical component supporting the diagnosis. In vascular cognitive impairment, MRIs typically display a pattern of diffuse and confluent changes in the white matter of the brain (Figure 20), cerebral microhemorrhages, and/or cortical infarcts beyond the mild periventricular hyperintensities commonly seen in older patients. The presence of severe extracranial or intracranial vascular disease also supports this diagnosis.

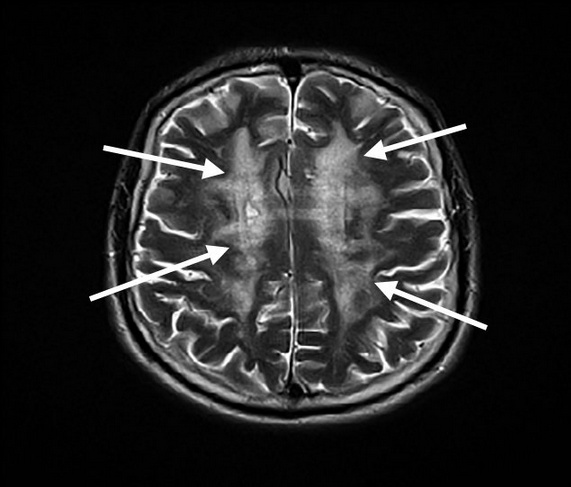

Axial T2-weighted MRI of the brain showing diffuse subcortical white matter hyperdensities (arrows) in the bilateral hemispheres. These findings are consistent with a severe microangiopathy seen in advanced vascular cognitive impairment.

Axial T2-weighted MRI of the brain showing diffuse subcortical white matter hyperdensities (arrows) in the bilateral hemispheres. These findings are consistent with a severe microangiopathy seen in advanced vascular cognitive impairment.

Treatment

Medications useful in treating Alzheimer disease are not approved for use in vascular cognitive impairment. However, some evidence suggests a modest benefit of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in vascular cognitive impairment, and treatment with this class of medications is generally recommended. Trials with memantine additionally indicated a modest cognitive benefit. However, aggressive treatment of vascular risk factors may be most beneficial.

Rapidly Progressive Dementia

Because of the many possibly treatable causes of rapidly progressive dementia, a systematic approach is required and can identify the underlying cause in most patients. The differential diagnosis includes Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), paraneoplastic syndromes, autoimmune/inflammatory encephalopathy (lupus encephalopathy, Sjögren syndrome, Hashimoto encephalopathy, multiple sclerosis), granulomatous disease (central nervous system sarcoidosis, Behçet syndrome, neurosyphilis), vasculitis (primary or secondary), some infections (HIV, herpes simplex virus, Borrelia burgdorferi–caused disease), and toxicities (from alcohol or drug abuse, exposure to heavy metals).

CJD is a potentially transmissible prion-related disorder that often presents with rapidly progressive dementia. Time from disease onset to death is approximately 12 months in as many as 80% of patients with CJD. The rapid cognitive decline seen with this disorder is associated with myoclonus, gait problems, and interruption of the circadian rhythm. MRI is one of the most sensitive diagnostic tools for CJD, typically showing a pattern of increased intensity in the diffusion-weighted sequence in the basal ganglia and various cortical regions. Periodic sharp wave complexes are often seen on electroencephalography and are helpful but not necessary in making the diagnosis. CSF testing may establish the presence of 14-3-3 protein and an elevation in total tau protein levels.

Paraneoplastic syndromes can also present with rapidly progressive dementia, and many of these disorders are treatable if diagnosed early (see Neuro-oncology for further discussion of these syndromes).

Delirium

Although rarely considered in the same light as acute dysfunction of other major organs, delirium is an acute alteration of brain function and should be approached with the same intent of alleviating the dysfunction as rapidly as possible. The clinical consequences of delirium are substantial because delirium is associated with greater hospital morbidity, more medical complications, longer lengths of stay, and a higher rate of discharge to long-term care facilities. The frequency of delirium depends on the setting and the patient population. Postsurgical and ICU patients, particularly older populations, have the highest prevalence of delirium. Risk also increases with the presence of baseline dementia, multiple medical problems, polypharmacy, and hypoxia.

Prevention of delirium is likely more effective than treatment of established delirium. In hospitalized patients, providing patients with assistive visual and hearing devices, adequately controlling pain, limiting psychoactive medications, frequent orientation, encouraging mobility, and enabling uninterrupted sleep on a normal sleep-wake cycle may help decrease the likelihood of developing delirium.

Delirium presents with numerous and variable symptoms and signs (Table 29). The core of delirium is an alteration in the arousal system (that is, in the ascending reticular activating system of the midbrain, thalamus, and hypothalamus that modulates sleep-wake transitions). Fluctuations in mental status, altered circadian rhythm, and poor attention are the hallmarks of the clinical syndrome. The Confusion Assessment Method is a useful tool with good sensitivity for diagnosing delirium. It includes assessment of onset and course, inattention, disorganized thinking, and level of consciousness.

Delirium also has a multitude of causes (Table 30), and almost any acute medical condition may provoke delirium in a susceptible patient. Evaluation for the underlying cause of delirium is mandatory but often difficult because the patient may not be able to direct the evaluation. Consideration should always be given to life-threatening causes of delirium, including vascular events and infection. Neuroimaging may be necessary, and in the appropriate setting, electroencephalography can be used to ensure that seizures are not the cause of the confusion.

Treatment

The primary treatment of delirium is identification and treatment of the underlying cause. Use of sedating medications, such as benzodiazepines and haloperidol, should be avoided because they may cause or worsen delirium. Current evidence does not support routine use of haloperidol or second-generation antipsychotic agents to treat delirium in adult inpatients. Some evidence suggests that the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon may be useful. The effectiveness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors remains uncertain.