Autoimmune Bullous Diseases

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

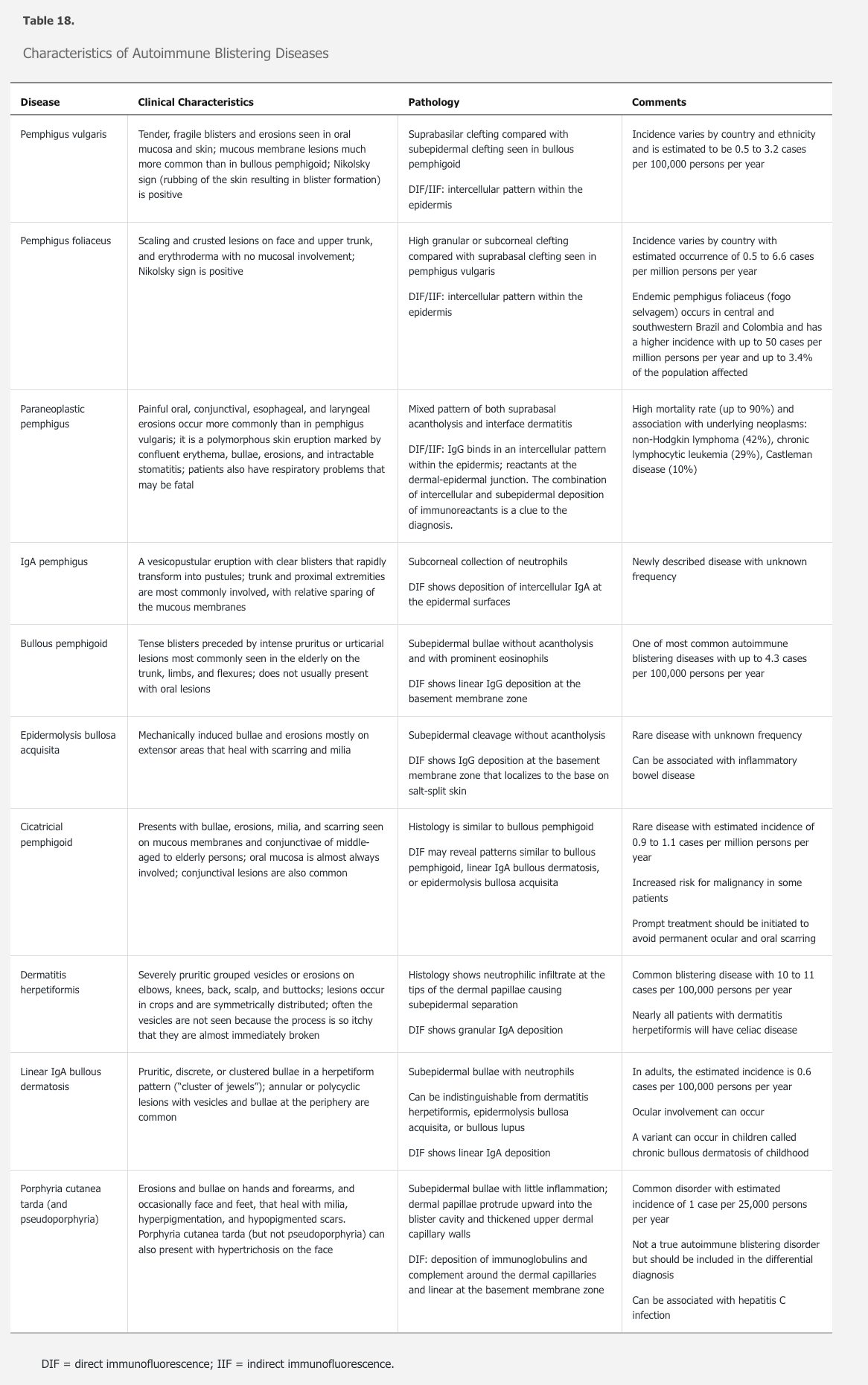

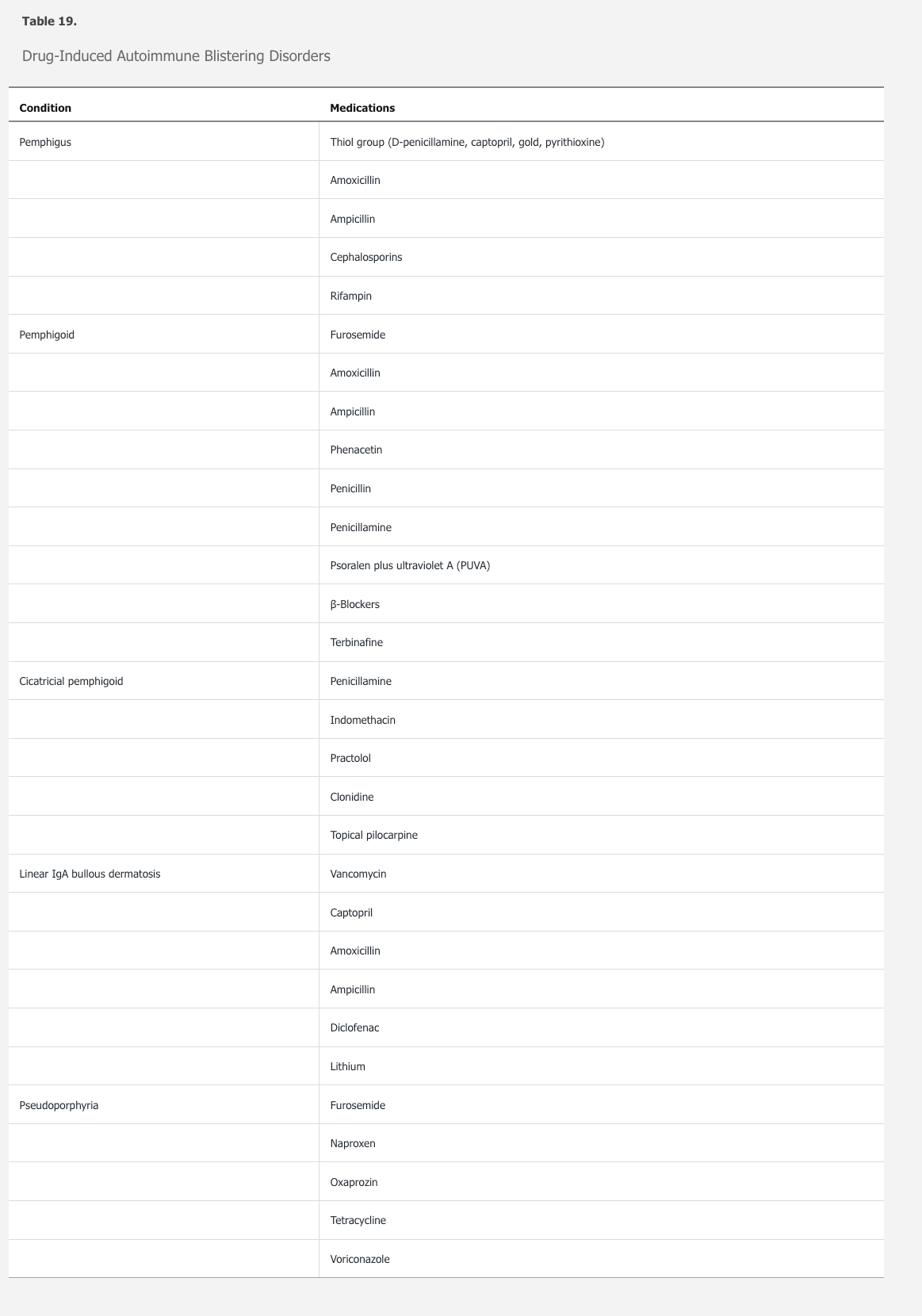

Bullous or blistering dermatoses can be acquired from an autoimmune process or from a genetic defect and are characterized by blistering or erosion of the skin. Autoimmune bullous diseases (ABDs) are caused by antibodies interfering with cohesion between keratinocytes of the epidermis (desmosomes) or between the epidermis and dermis (basement membrane zone) (Table 18). ABDs can be subdivided into intraepidermal and subepidermal disorders. Intraepidermal ABDs present with flaccid vesicles that rupture easily, whereas subepidermal ABDs show intact, tense bullae. Although most of the ABDs are idiopathic, medications can also cause variants of almost all the disorders, and a thorough medication review is essential (Table 19).

Diagnosis

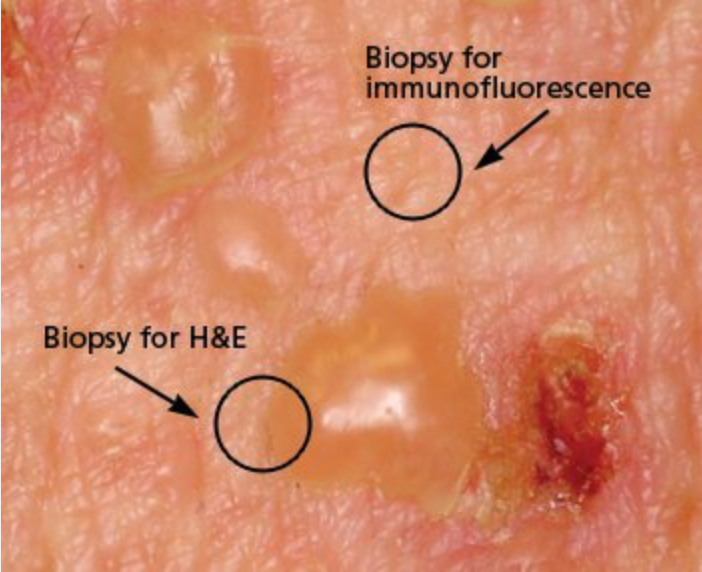

The most sensitive method for the diagnosis of ABD is a skin biopsy. A skin (shave or punch) biopsy of an intact, early vesicle or bullae with adjacent normal skin should be submitted in formalin and processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Each of the ABDs has characteristic histologic findings that suggest a differential diagnosis. In addition, a biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) in Michel transport medium should be performed. For optimal sensitivity, biopsies for DIF should be from noninvolved perilesional skin. The histologic findings together with the pattern on DIF can usually render a diagnosis.

The most sensitive method for diagnosis is with two biopsies: one of lesional skin for histology, and one of perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence, as shown.

Bullous pemphigoid is the most common subepidermal ABD and overall the most common ABD. Onset is usually in adults 60 years of age and older and presents with urticarial and eczematous lesions that progress to tense bullae on an erythematous base (Figure 94). Oral involvement is present in approximately 20% of patients. There are varying degrees of pruritus with bullous pemphigoid. Bullae heal with pigment change but otherwise do not scar. It typically has a protracted course with exacerbations and remission. In the past, morbidity was high, but steroid-sparing agents result in successful management.

Bullous pemphigoid is characterized by subepidermal bullae blisters that are tense and do not rupture easily. It predominantly involves nonmucosal surfaces. Sites of predilection are the lower abdomen, inner thighs, groin, axillae, and flexural aspects of the arms and legs.

Bullous pemphigoid is characterized by subepidermal bullae blisters that are tense and do not rupture easily. It predominantly involves nonmucosal surfaces. Sites of predilection are the lower abdomen, inner thighs, groin, axillae, and flexural aspects of the arms and legs.

Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common intraepidermal ABD, and its incidence increases with age. It presents with oral or vaginal erosions and flaccid vesicles that rupture easily and leave erosions (Figure 95). Pemphigus vulgaris has a positive Nikolsky sign whereby light lateral friction on perilesional skin induces a blister. Lesions heal with pigment change but otherwise do not scar. Prior to the use of oral glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing agents, mortality was high owing to secondary infection and sepsis.

The flaccid, intraepidermal vesicle of pemphigus vulgaris are readily broken, leaving behind weeping erosions.

The flaccid, intraepidermal vesicle of pemphigus vulgaris are readily broken, leaving behind weeping erosions.

Pemphigus foliaceus is a superficial intraepidermal ABD that is most common in middle-aged adults. It presents with crusted erosions on the scalp, head/neck, and trunk without mucous membrane involvement (Figure 96). It can be associated with autoimmune diseases, in particular lupus erythematosus.

The superficial blisters in pemphigus foliaceus result in multiple erosions and crusting (similar to “corn flakes”). Intact vesicles are not seen regularly.

The superficial blisters in pemphigus foliaceus result in multiple erosions and crusting (similar to “corn flakes”). Intact vesicles are not seen regularly.

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a subepidermal ABD with a varied clinical presentation with onset in adulthood. Unlike bullous pemphigus, classic epidermolysis bullosa acquisita presents at sites of friction or trauma (hands, elbows, buttocks, axillae) with tense bullae that are not on an erythematous base. It heals with scarring (milia). Because of the generally noninflammatory nature of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, treatment is difficult and avoidance of trauma is an important aspect of the regimen.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a subepidermal ABD that is extremely pruritic. It is a lifelong condition with onset in adulthood. There are small tense vesicles and papules, which are rarely intact, presenting as excoriations on the elbows, knees, and buttocks (Figure 97). Most patients have celiac disease. A gluten-free diet is first-line treatment for dermatitis herpetiformis, but additional therapy with dapsone is often is required. Before initiating therapy with dapsone, patients should be checked for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is an autoimmune bullous disease that causes intensely pruritic small papulovesicles classically grouped on the scalp, elbows, knees, back, and buttocks. Due to intense pruritus, erosions and excoriations are the most common clinical finding.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is an autoimmune bullous disease that causes intensely pruritic small papulovesicles classically grouped on the scalp, elbows, knees, back, and buttocks. Due to intense pruritus, erosions and excoriations are the most common clinical finding.

Management of ABDs depends on the symptoms, extent of disease, and associated comorbidities. For localized disease, topical or intralesional glucocorticoids may be sufficient. Because the epidermal barrier is disrupted in these conditions, secondary bacterial infection can lead to exacerbations. In general, treatments for ABD are not FDA approved and recommendations are based on expert opinion, consensus, and published evidence. The goal is to decrease circulating antibodies with the subsequent elimination of antibodies binding to skin antigens and the restoration of function. Initial treatment is with prednisone until no new vesicles or blisters are present. This is followed by a slow taper and the addition of a steroid-sparing agent. Recently rituximab has been shown to have high efficacy in pemphigus vulgaris.