Approach to the Patient with Rheumatologic Disease

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

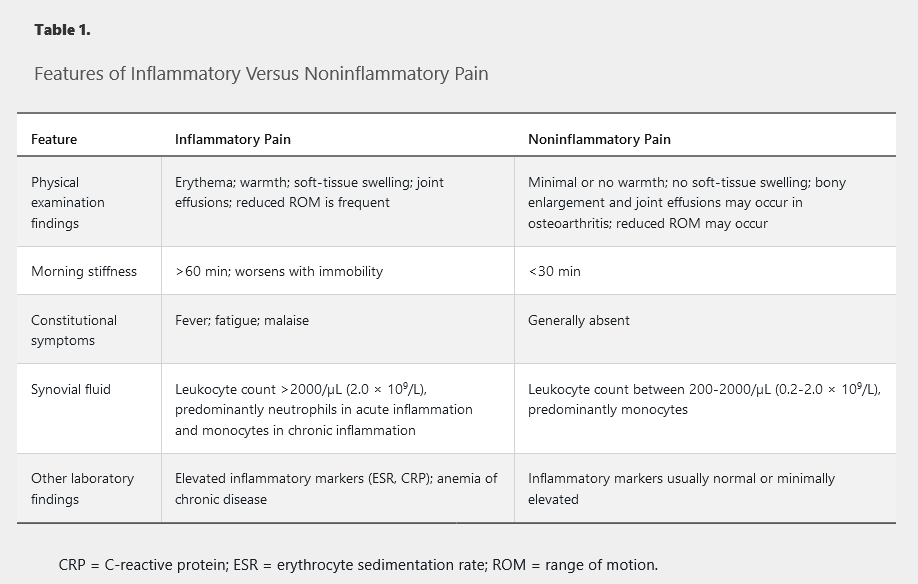

Inflammatory Versus Noninflammatory Pain

The differentiation between inflammatory and noninflammatory signs and symptoms is central to the evaluation of patients with musculoskeletal pain. Autoimmune conditions typically present with inflammation, whereas mechanical or degenerative disorders are characteristically noninflammatory. The cardinal signs of inflammation are pain, erythema, swelling, and warmth; with the exception of pain, noninflammatory conditions usually lack these features. Importantly, patients may simultaneously experience more than one type of pain. Table 1 compares the features of inflammatory and noninflammatory pain.

The Musculoskeletal Examination

An accurate history and a thorough musculoskeletal physical examination are essential to diagnose and differentiate inflammatory and noninflammatory symptoms and can help to avoid unnecessary testing. Musculoskeletal pain may be articular, periarticular, or referred. Pain with passive range of motion suggests an articular condition, whereas pain with active range of motion suggests a periarticular condition.

Arthritis

Monoarthritis

Monoarthritis involves a single joint and is classified as acute or chronic. Acute monoarthritis can be noninflammatory (for example, trauma, hemarthrosis, or internal derangement) or inflammatory (for example, crystal induced or infectious). Evaluation for infectious arthritis should be guided by the clinical presentation and examination, but suspicion should always be high. Joint aspiration is usually the most effective means of diagnosing the underlying cause.

Chronic inflammatory monoarthritis (>6 weeks) can be caused by chronic infection (for example, mycobacterial, fungal, or Borrelia burgdorferi) or by autoimmune rheumatologic disease. Synovial fluid analysis will confirm inflammation but may be inadequate for diagnosis; assessment for systemic disease (serologies and other laboratory studies) and, in some cases, synovial biopsy may be required.

Chronic noninflammatory monoarthritis is usually caused by osteoarthritis.

Oligoarthritis

Oligoarthritis involves two to four joints, typically in an asymmetric pattern. Acute inflammatory oligoarthritis may be caused by gonorrhea or rheumatic fever. Chronic inflammatory oligoarthritis can be caused by autoimmune conditions such as spondyloarthritis.

Chronic noninflammatory oligoarthritis is usually caused by osteoarthritis.

Polyarthritis

Polyarthritis involves five or more joints. In many cases, it involves the small joints of the hands and/or feet. Acute polyarthritis (<6 weeks in duration) can be caused by viral infections (for example, parvovirus B19, HIV, hepatitis B virus, or rubella) or may be an early manifestation of a chronic inflammatory polyarthritis (>6 weeks in duration) such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or psoriatic arthritis.

Soft-Tissue Abnormalities

Common nonarticular sources of musculoskeletal symptoms are the soft tissues (tendons, ligaments, and bursae) around or away from the joints. Isolated tendon and/or ligament involvement is usually suggestive of noninflammatory disorders such as mechanical injury/irritation, overuse, or degeneration (for example, rotator cuff disorders or tennis elbow). Disorders of widespread musculoskeletal pain (such as fibromyalgia) also have symptoms localizing to these structures.

Extra-Articular Manifestations of Rheumatologic Disease

Constitutional Symptoms

Fever, morning stiffness, and fatigue occur in numerous rheumatologic conditions. Fever is usually low grade but may be high and spiking in some conditions (for example, adult-onset Still disease and autoinflammatory diseases). Morning stiffness lasting more than 60 minutes is most commonly described in rheumatoid arthritis but also occurs in other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Significant and even disabling fatigue is a prominent feature of fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome.

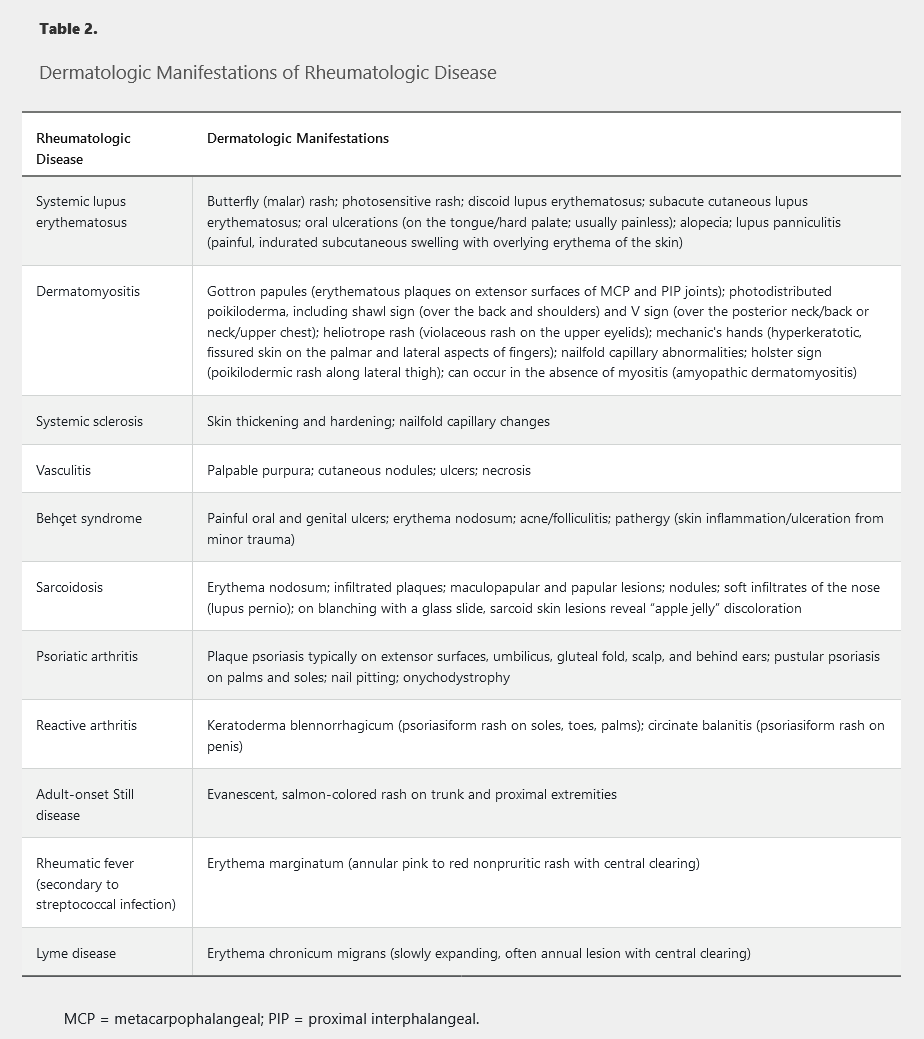

Skin Involvement

Skin involvement is common in rheumatologic conditions and may go unnoticed by the patient (Table 2). Skin involvement may also occur as an adverse effect of medications used to treat rheumatologic conditions, including skin infections secondary to immunosuppressive therapy.

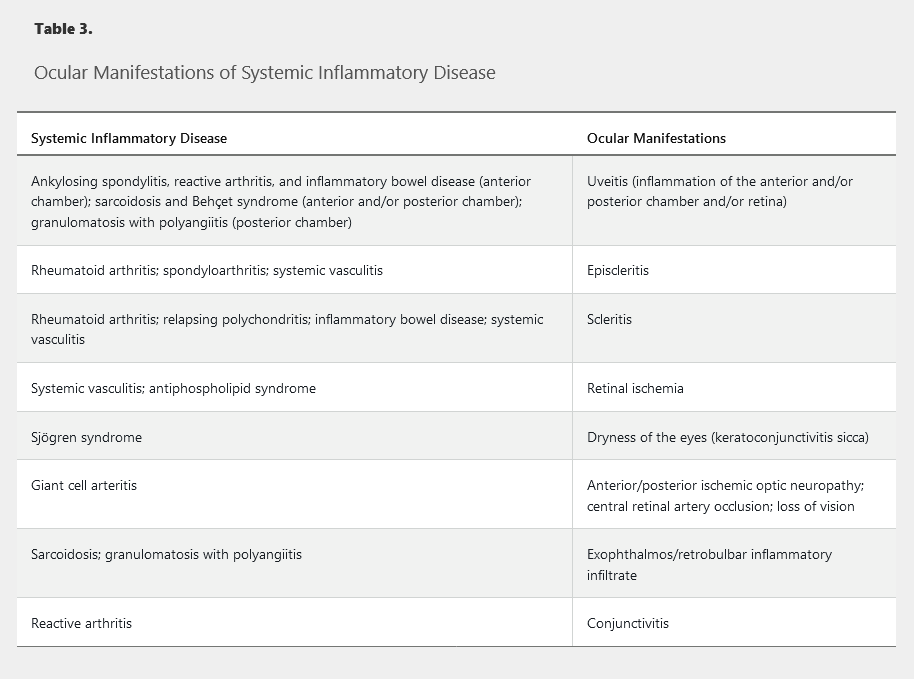

Eye Involvement

Eye involvement in different rheumatologic diseases usually follows fairly distinct patterns, and the location and type of involvement can help narrow the differential diagnosis (Table 3). If not quickly recognized and treated, certain forms of eye involvement can have devastating consequences, including permanent loss of vision.

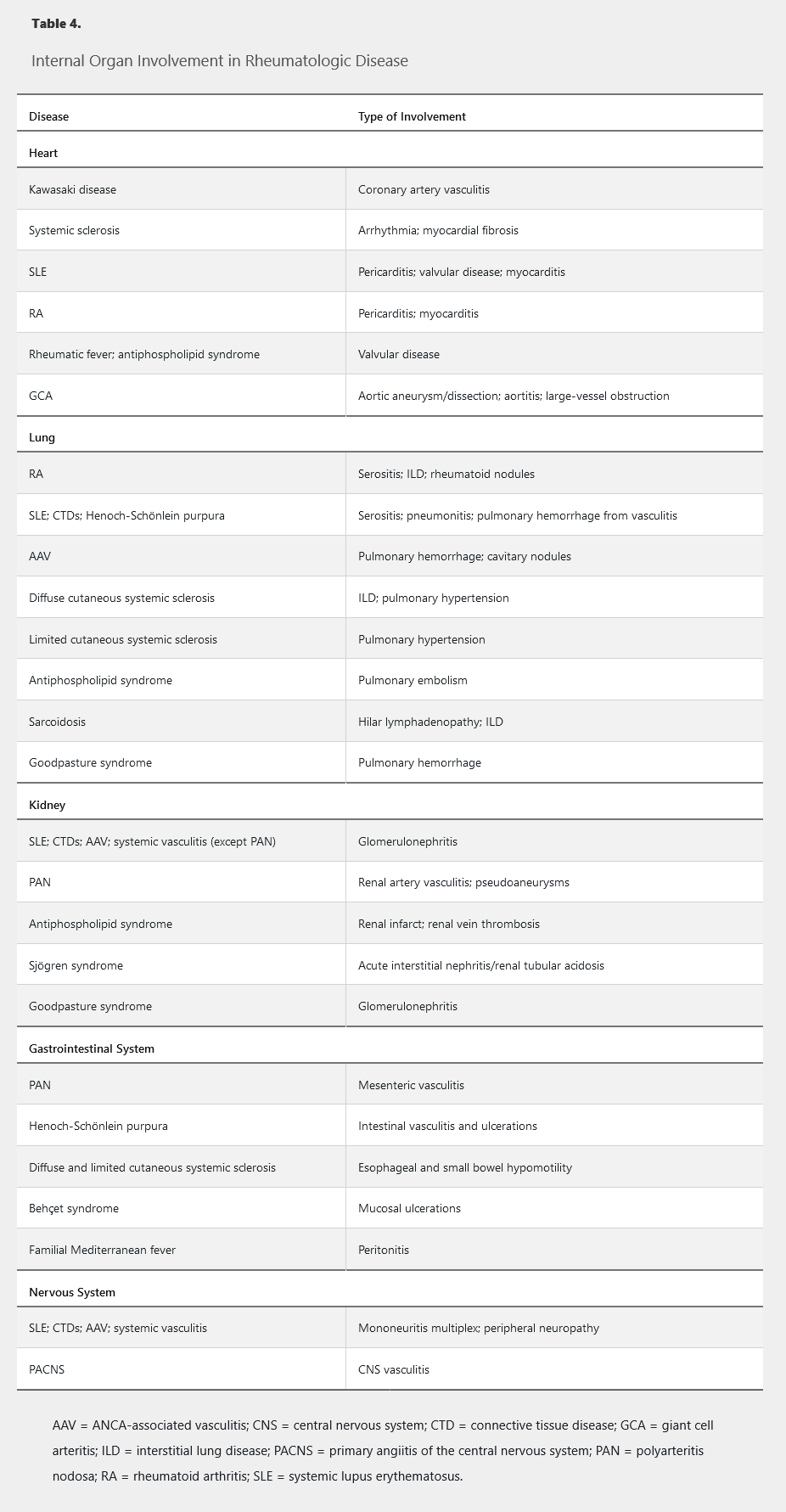

Internal Organ Involvement

Rheumatologic diseases frequently affect internal organs, with different diseases tending to follow characteristic patterns (Table 4).

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies are useful for diagnosing rheumatologic diseases, identifying the extent/severity of involvement, evaluating disease activity, and monitoring therapeutic responses. Because of limited specificity, these tests should always be interpreted in the context of the clinical history and physical examination and should be used with great caution, if at all, in the setting of low pretest probability.

Tests That Measure Inflammation

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) measures the fall of erythrocytes (mm/h) through anticoagulated plasma. Erythrocytes tend to be negatively charged on their surfaces, leading to repulsion and a prolonged ESR. Fibrinogen and other acute phase reactants neutralize the erythrocytes' surface charges, promoting their ability to settle at a faster rate.

Elevated fibrinogen levels and high ESRs are seen in many rheumatologic diseases, as well as in nonrheumatologic inflammatory conditions such as chronic infections and malignancies.

The normal ESR increases with age and is usually higher in women. A well-accepted rule of thumb is to adjust the upper limit of normal as age in years divided by 2 for men and (age in years + 10)/2 for women.

In addition to inflammatory conditions, elevated ESRs can be seen in pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, and end-stage kidney disease. Due to rheostatic properties, anemia and macrocytosis are also associated with an increased ESR. An excessively low ESR can occur in low fibrinogen states such as liver or heart failure and in conditions promoting rouleaux formation (for example, polycythemia vera). Sickle cell disease and microcytosis (including spherocytosis) may also lower ESR.

A markedly elevated ESR (>100 mm/h) should alert physicians to conditions such as giant cell arteritis, multiple myeloma, metastatic cancer, or other overwhelming inflammatory states (infection or autoimmune disease).

C-Reactive Protein

C-reactive protein (CRP) is produced by the liver mainly in response to interleukin-6 generated by leukocytes during the inflammatory state. CRP levels and ESR usually follow a common pattern, but CRP is often more rapidly responsive to changes in inflammation. In rheumatologic conditions, CRP is typically elevated 2 to 10 times the normal level; a higher level (especially >10 mg/dL [100 mg/L]) should prompt consideration of an alternative diagnosis such as infection. CRP is thought to be a better marker than ESR in measuring inflammation in spondyloarthritis. In contrast, in some patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the CRP may remain normal despite active disease. CRP can be elevated in obesity, and a low CRP can occur with the use of certain antibiotics and interleukin-6 blockers.

Complement

The complement system is an essential part of the immune response, promoting vasodilation, attracting leukocytes, and assisting in the lysis of opsonized bacteria during humoral immunity.

Complement components are acute phase reactants and rise in many inflammatory states. However, in response to immune complex formation diseases (SLE and cryoglobulinemic and urticarial vasculitis) and certain other states, complement cascades are activated, and complement levels fall due to excessive consumption. Paradoxically, genetic deficiency of early complement components may increase the risk for lupus-like autoimmune diseases.

C3 and C4 are the commonly measured complement components. The CH50 assay should not be performed routinely due to cost and limited utility.

Autoantibody Tests

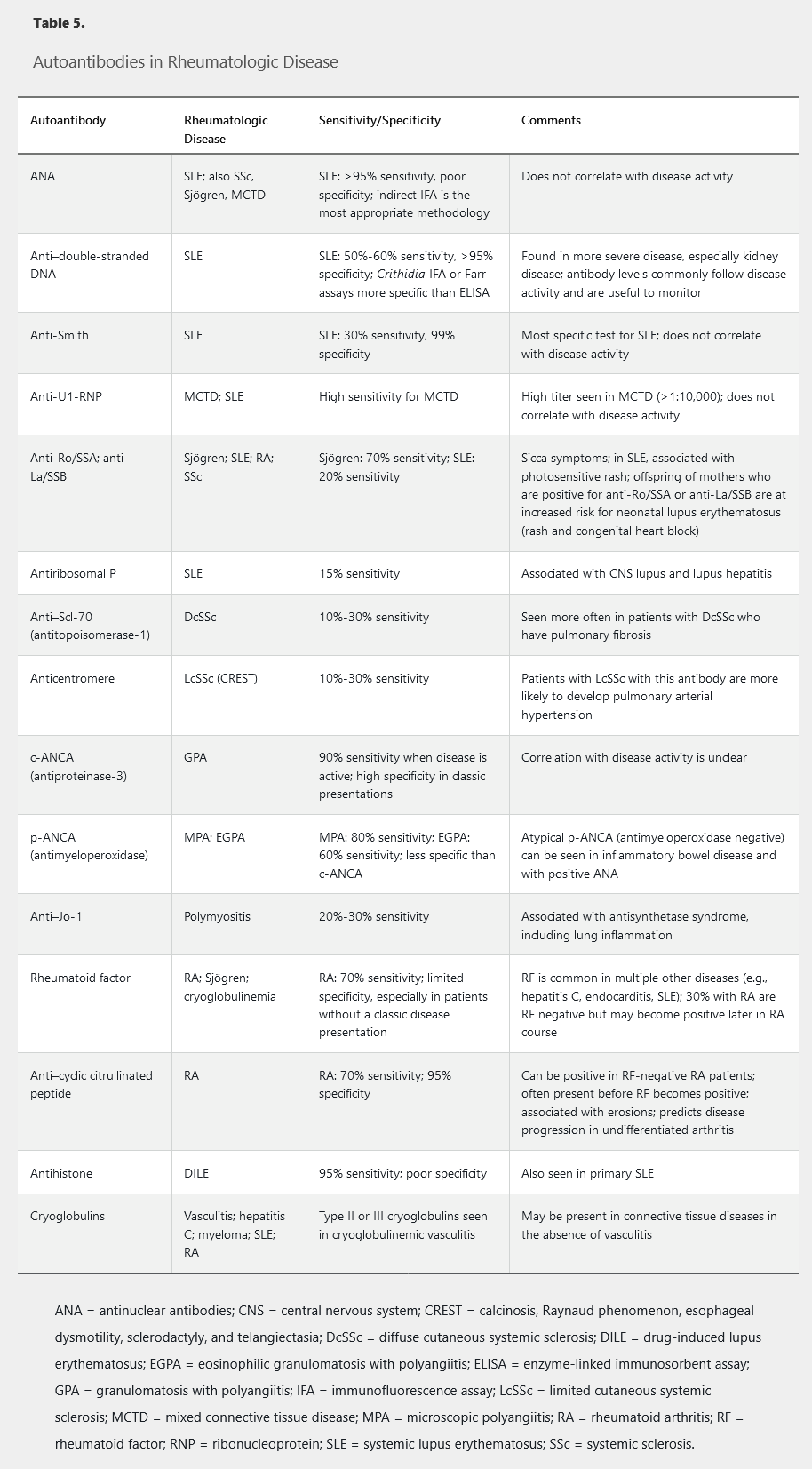

Rheumatologic diseases are commonly associated with autoantibodies, but their presence does not equate with the diagnosis of an underlying condition because they lack specificity and may be seen in other conditions and healthy persons. In commercial laboratories, autoantibody testing has been automated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in a sequential algorithm, which may simplify physician assessment but tends to have reduced sensitivity and specificity.

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are directed against nuclear antigens and are traditionally associated with SLE. About one third of the healthy population has a low-titer (1:40) ANA, and 3% to 5% have a titer of 1:160 or more. ANA can also be seen in other autoimmune conditions, infection, and malignancy, and it may be drug induced. An isolated positive ANA with nonspecific symptoms and normal clinical examination does not establish the diagnosis of a connective tissue disease.

A higher titer of ANA is more often associated with an underlying rheumatologic disease, although not always SLE. However, almost all patients with SLE (>95%) have a positive ANA. ANA titer does not correlate with disease activity and should not be used for activity assessment.

ANA specificity or subserology testing (that is, testing for antibodies to specific nuclear components such as DNA or centromeres) should be reserved for patients with a positive ANA and a clinical syndrome suggestive of an underlying connective tissue disease. ANA subserology testing should not be routinely performed, even in the setting of a positive ANA, without a strong clinical suspicion of underlying connective tissue disease.

Table 5 provides details on these and other autoantibodies and their associations with specific conditions.

- Anti-cytosolic 5'-nucleotidase 1A antibody: inclusion body myositis

- anti-histidyl-tRNA synthetase: with subset anti-Jo-1. ILD inflammatory myopathies, antisynthetase syndrome

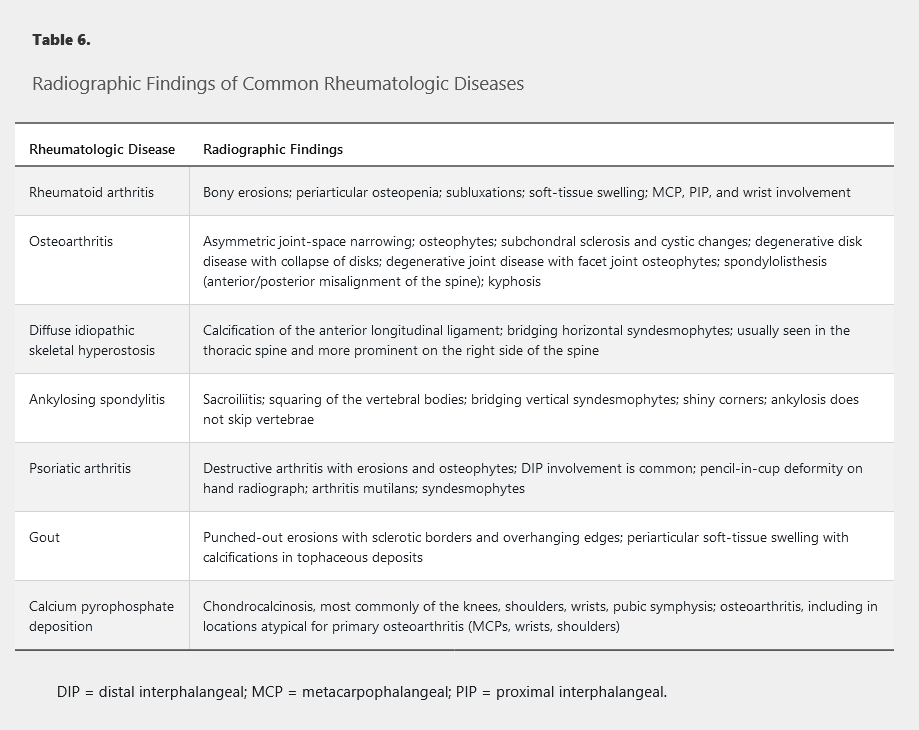

Imaging Studies

Radiography

Plain radiography is an essential modality in the evaluation of many rheumatologic diseases and can assess and differentiate inflammatory arthritis, osteoarthritis, and crystal arthropathies (Table 6). Plain radiography has limitations because it gives a two-dimensional picture of three-dimensional structures, is limited in its ability to visualize soft tissues, and may not detect early or small erosive changes. Despite these limitations, plain radiography is usually the first imaging test ordered in the evaluation of rheumatologic diseases because it is readily available, is inexpensive, exposes patients to only a low level of ionizing radiation, and is useful in monitoring arthritis progression.

CT

CT provides multiple views and orientations from a single study but is more useful for bony abnormalities than for soft-tissue inflammation or fluid collections. CT is more sensitive for detecting bone erosions than plain radiographs or MRI. However, CT is more expensive than plain radiography and exposes the patient to more radiation.

MRI

MRI is the most sensitive routine radiologic technique for detecting soft-tissue abnormalities, inflammation, and fluid collections but is less effective than CT in demonstrating bony abnormalities or erosions. MRI is sensitive for detecting early spine and sacroiliac joint inflammation and may be indicated for the evaluation of suspected spondyloarthritis if plain radiographs are negative. MRI does not expose patients to radiation but is associated with high cost, limited availability, and possible patient intolerance due to claustrophobia or body habitus. The American College of Rheumatology Choosing Wisely list recommends against routine MRI of the peripheral joints to monitor RA due to inadequate data supporting its use.

Ultrasonography

The use of ultrasonography to evaluate patients with rheumatologic diseases has expanded dramatically in the past 10 years. Ultrasonography is relatively inexpensive, can scan across three-dimensional structures, and can provide real-time data in the clinic without exposure to ionizing radiation. It can assess soft-tissue abnormalities, including synovitis, tendonitis, bursitis, and effusions; assess disease activity using Doppler; and assist with tendon or joint injections. However, it is operator dependent, and training/practice is needed to achieve competence.

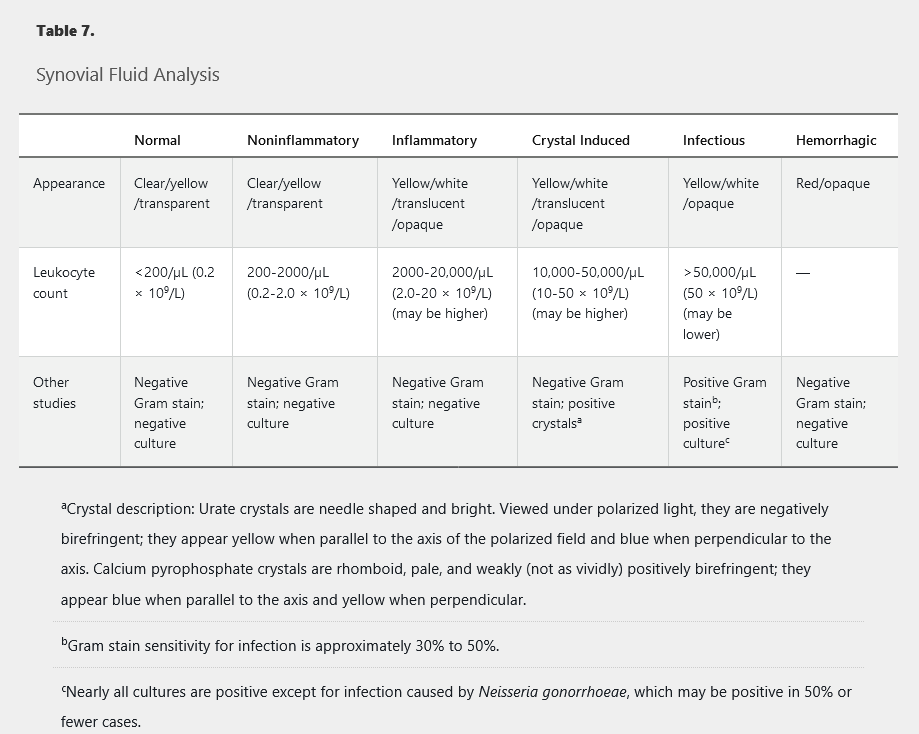

Joint Aspiration

Joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis are essential for discriminating between inflammatory and noninflammatory effusions or for distinguishing between infectious arthritis and acute crystal arthropathies. In the evaluation of any monoarthritis or when infection is being considered, joint aspiration should be performed to diagnose the underlying cause. Aspirated synovial fluid should be sent for leukocyte count, Gram stain, and cultures, as well as evaluation for crystals under polarized light. See Table 7 for more information.

There is no absolute cutoff of synovial fluid leukocyte counts for ruling out infectious arthritis; however, counts greater than 50,000/µL (50 × 109/L) with polymorphonuclear cell predominance have a high likelihood of infection. Counts less than 2000/µL (2.0 × 109/L) are usually associated with noninflammatory etiologies. Notably, crystals can coexist with infection, and their presence does not rule out infection if suspicion is high.

Tissue Biopsy

When appropriate, tissue biopsy of involved organs can be helpful in diagnosing numerous rheumatologic conditions such as vasculitis (lung, kidney, or temporal artery biopsy) and SLE (skin biopsy). Tissue biopsy may also help assess disease activity (for example, kidney biopsy in SLE). The benefits should be appropriately balanced with possible risks of the procedure.