urinalysis

- related: Nephrology

- tags: #nephrology

Interpretation of the Urinalysis

Urine dipstick and urine microscopy are indicated in the evaluation of both acute and chronic kidney disease. Analysis is best performed on a fresh specimen within 30 to 60 minutes of voiding. Midstream collection is preferred with a clean catch in women and uncircumcised men.

Urine Dipstick

Specific Gravity

Specific gravity measures hydration status and reflects the kidney's ability to concentrate urine.

pH

Low urine pH may occur in persons eating high-protein diets. High alkaline pH ≥7.0 can occur in strict vegetarians and in persons with infections caused by urea-splitting organisms. Urine pH may be inappropriately high in some forms of renal tubular acidosis (type 1 distal) but may be appropriately low in others (type 4 distal).

Blood

Dipsticks detect peroxidase activity of blood and free heme pigments (hemoglobin and myoglobin). Three or more erythrocytes result in a positive test (1+ blood). A positive test in the absence of erythrocytes in the urine sediment may indicate myoglobinuria (due to rhabdomyolysis) or hemoglobinuria (due to intravascular hemolysis, transfusion, or shear stress related to mechanical heart valve and perivalvular leak). False-positive tests may occur with other substances with peroxidase activity, including peroxidase-expressing bacteria and drugs such as rifampin or chloroquine. Ascorbic acid can cause a false-negative result. Medications (rifampin, phenytoin) or food (beets) can cause red-colored urine that is heme negative.

Protein

Although various proteins may be present in urine, the dipstick preferentially detects albumin. Because dipsticks are dependent on urine concentration, false negatives may result from dilute urine and false positives from highly concentrated urine. Because moderately increased albuminuria (microalbuminuria) may go undetected by dipstick, direct quantification of albuminuria and/or proteinuria using a random (spot) protein-creatinine ratio or albumin-creatinine ratio or a 24-hour urine collection is required in high-risk patients. False-positive tests can occur with highly alkaline urine specimens.

More than 0.5g/g proteinuria is abnormal

Glucose

Glucosuria typically occurs when plasma glucose exceeds 180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L). Glucosuria in the absence of hyperglycemia suggests proximal tubular dysfunction, as seen with myeloma or exposure to drugs (including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors such as empagliflozin and canagliflozin). Glucosuria may be present in normal pregnancy due to changes in tubular threshold for glucose reabsorption.

Ketones

Ketonuria is most commonly seen in starvation, diabetic ketoacidosis, and alcoholic ketoacidosis. Urine ketones are also seen in salicylate toxicity and isopropyl alcohol poisoning. Urine dipstick detects acetone and acetoacetate but not β-hydroxybutyrate; therefore, in diabetic ketoacidosis and alcoholic ketoacidosis where β-hydroxybutyrate is the primary ketone, the dipstick underestimates ketone excretion. False-positive tests may occur with drugs containing sulfhydryl groups, such as captopril.

Leukocyte Esterase and Nitrites

Leukocyte esterase is an enzyme present in leukocytes. A positive test suggests pyuria (≥5 leukocytes/hpf).

A positive nitrite test signifies the presence of gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia c_oli_; Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, and Proteus species) capable of converting urine nitrates into nitrites. The test is falsely negative if there is inadequate contact time for urine nitrates with the bacteria. The nitrite test is negative in urinary tract infection (UTI) caused by nonconverting organisms (Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, or Haemophilus species).

The presence of both leukocyte esterase and nitrites on urine dipstick is highly predictive of a UTI; conversely, the absence of both has a high negative predictive value for a UTI.

Bilirubin

Bilirubin should be absent from the urine when serum levels are normal. Conjugated, water-soluble bilirubin is excreted in the urine in severe liver disease or obstructive hepatobiliary disease.

Urobilinogen

Gut bacteria produce urobilinogen through metabolism of bilirubin. Urobilinogen is then absorbed via portal circulation and excreted in urine. Increased urobilinogen is associated with hemolytic anemia or parenchymal liver disease. Decreased levels are seen with severe cholestasis and obstructive disease.

Key Points

- Because moderately increased albuminuria (microalbuminuria) may go undetected by dipstick, direct quantification using a random (spot) protein-creatinine ratio or albumin-creatinine ratio or a 24-hour urine collection is required in high-risk patients.

- The urine nitrite test is negative in urinary tract infections caused by nonconverting organisms (Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, or Haemophilus species).

- The presence of both leukocyte esterase and nitrites on urine dipstick is highly predictive of a urinary tract infection (UTI); conversely, the absence of both has a high negative predictive value for a UTI.

Urine Microscopy

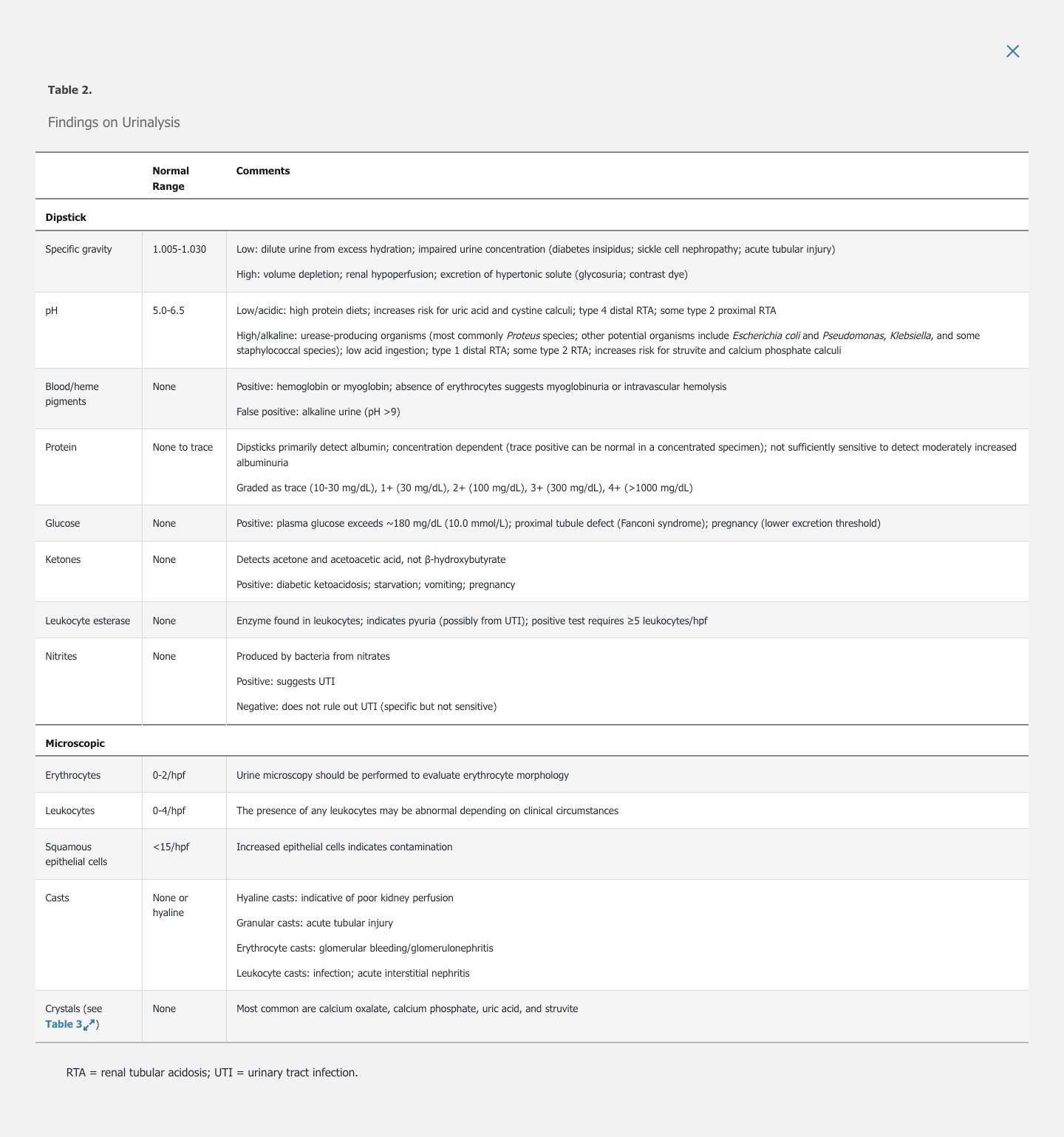

Microscopic assessment of urine sediment (Figure 2) is indicated for patients with abnormalities on dipstick and in those with acute kidney injury, newly diagnosed chronic kidney disease, or suspected glomerulonephritis. See Table 2 for details on urine microscopy.

Erythrocytes

Erythrocyte morphology may indicate their origin (see Figure 2). Isomorphic erythrocytes (round and of consistent size) suggest a nonglomerular origin as a result of infection, mass, cyst, or stone. Glomerular bleeding may be associated with erythrocyte fragmentation, leading to dysmorphic appearances with significant variability. Acanthocytes, a form of dysmorphic erythrocytes characterized by vesicle-shaped protrusions, are most suggestive of a glomerular source of bleeding and should result in prompt evaluation for glomerulonephritis (Figure 3). See Clinical Evaluation of Hematuria for more information.

Leukocytes

The presence of ≥5 leukocytes in the urine sediment indicates pyuria, which is most commonly caused by a UTI. Sterile pyuria is the presence of urine leukocytes in the setting of negative urine culture; common causes include vaginitis and cervicitis in women, prostatitis in men, acute interstitial nephritis (AIN), kidney stones, kidney transplant rejection, and, less commonly, UTIs due to organisms that do not grow by standard culture techniques (Chlamydia species, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Ureaplasma urealyticum). The absence of leukocytes does not rule out AIN.

Eosinophils

Urine eosinophils suggest interstitial nephritis, atheroembolic disease, glomerulonephritis, small-vessel vasculitis, UTI, prostatic disease, or parasitic infections. Poor sensitivity and specificity limit the utility of urine eosinophils in the diagnosis of interstitial nephritis.

Epithelial Cells

Renal tubular, transitional, and squamous epithelial cells may be seen on urinalysis (see Figure 2). Renal tubular epithelial cells are round with central nuclei and are 1.5 to 3 times larger than leukocytes. Their presence in the context of granular casts suggests acute tubular necrosis. Transitional epithelial cells are slightly larger than renal tubular epithelial cells and may be binucleate; they originate anywhere from the renal pelvis to the proximal urethra. Squamous epithelial cells are the largest epithelial cells, and are flat and irregular with small central nuclei; they are derived from the distal urethra or external genitalia, and their presence in large numbers (>15/hpf) denotes contamination by genital secretions.

Casts

The backbone of all urine casts is a matrix composed of Tamm-Horsfall protein (uromodulin). These cylindrical casts form in the distal tubular lumen. Any cells or debris in casts were present in the tubule at the time of cast formation, therefore originating from a more proximal part of the nephron. Erythrocyte casts are highly suggestive of glomerulonephritis. Leukocyte casts may be present in AIN and infections (pyelonephritis). Pigmented or granular (muddy brown) casts contain tubular cell debris (Figure 4) and are present in acute tubular necrosis. The severity of acute kidney injury correlates with the number of casts and presence of renal tubular epithelial cells.

Crystals

Crystalluria results from the supersaturation of solutes in concentrated urine. These solutes are derived from metabolic disorders, inherited diseases, or drugs. Table 3 describes features of common crystals. Certain drugs can crystallize in concentrated urine and when used in high doses, including sulfadiazine, sulfamethoxazole, intravenous acyclovir, methotrexate, and atazanavir.

Key Points

- Isomorphic erythrocytes suggest a nonglomerular origin of blood; dysmorphic erythrocytes, particularly acanthocytes, suggest a glomerular origin.

- Erythrocyte casts are highly suggestive of glomerulonephritis, leukocyte casts may be present in acute interstitial nephritis and infections, and granular (muddy brown) casts are present in acute tubular necrosis.

Measurement of Albumin and Protein Excretion

Related Question

- Question 94

Assessment for urine protein is indicated in patients with any suspected kidney disease. Concurrent increased serum creatinine or abnormal findings on urine sediment raise concern for active kidney disease in any patient with proteinuria.

Assays to detect protein in the urine include urine dipstick, random (spot) urine protein-creatinine ratio or albumin-creatinine ratio, and 24-hour urine collections. Due to the challenges of 24-hour urine collections, the random urine albumin-creatinine ratio and protein-creatinine ratio have been widely adopted. Both random tests adequately determine the presence of albuminuria, but the urine protein-creatinine ratio also detects nonalbumin proteins. Random collections correlate well with timed collections and are sufficiently accurate for screening and monitoring proteinuria despite inaccuracies due to diurnal fluctuations of urine protein and interindividual differences in urine creatinine excretion. Table 4 outlines the definitions of proteinuria and albuminuria as well as normal values.

Urine albumin, when present at high levels, indicates glomerular injury; conversely, the absence of albuminuria essentially excludes most glomerular diseases. Smaller proteins are filtered at the level of the glomerulus but are reabsorbed by the proximal tubule; their presence in urine generally indicates tubulointerstitial disease. Light chains present at high levels, such as in monoclonal gammopathy, are detected on urine protein electrophoresis or free light chain assay.

Transient, nonpathologic, usually small elevations in urine protein can occur with acute illness or fever, rigorous exercise, and pregnancy. Orthostatic proteinuria is a benign proteinuria that increases when the patient is upright but decreases when the patient is recumbent. This condition is more common in adolescents but should be considered in those up to age 30 years. Split urine collection (daytime versus nighttime collection that includes first morning void) can evaluate this diagnosis.

The American College of Physicians (ACP) recommends against screening for chronic kidney disease, including screening for proteinuria in asymptomatic adults without risk factors for chronic kidney disease, because there is no evidence of benefit from early treatment to outweigh the harms of screening, including false-positive results and unnecessary testing and treatment. However, screening for proteinuria may be considered in high-risk patients, such as hypertensive, diabetic, and older patients.

In patients with diabetes mellitus, urine albumin screening is recommended due to its ability to detect early disease. The American Diabetes Association recommends yearly assessment in patients with type 2 diabetes, and assessment after 5 years of disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Because there is no evidence that monitoring proteinuria levels in patients taking ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers is beneficial or that reduced proteinuria levels translate into improved outcomes, ACP recommends against testing for proteinuria in adults with or without diabetes who are currently taking an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker.

Urine protein electrophoresis can characterize proteins, allowing for classification of the proteinuria as glomerular or tubular. It also detects monoclonal gammopathy, although it is less sensitive than light chain assay.

Key Points

- The random (spot) urine protein-creatinine ratio and albumin-creatinine ratio correlate with 24-hour urine collections and are sufficiently accurate for screening and monitoring proteinuria.

- High urine albumin levels indicate glomerular injury; the absence of albuminuria excludes most glomerular diseases.