Spondyloarthritis

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Overview

Spondyloarthritis refers to a group of arthritic disorders that tends to involve the spine and sacroiliac joints and share genetic, pathophysiologic, and clinical features. HLA-B27 is variably expressed but is more frequently present in this group of patients than in the general population. Peripheral arthritis, enthesitis (inflammation of the insertion points of tendons and ligaments onto bone), inflammatory eye disease, psoriatic rashes, and gastrointestinal and genitourinary inflammation may occur in varying degrees.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiologic processes involved in these disorders include T-cell activation and proliferation; elaboration of cytokines, particularly tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and the interleukins (IL)-1 and -23/17; and bony proliferation and destruction. Although the exact trigger for these processes is unknown, genetic and environmental factors are likely to play a role.

Genetic Factors

The most important genetic risk factor for spondyloarthritis is the presence of HLA-B27. The prevalence of HLA-B27 is high among Northern Europeans (about 6%) and low in Africans; accordingly, spondyloarthritis is seen with greater frequency in the former group. However, only 5% to 6% of those carrying HLA-B27 develop spondyloarthritis, and not all patients with spondyloarthritis are positive for HLA-B27. For these reasons, HLA-B27 should not be used as a screening test for these disorders, although its presence in a patient with a high pretest probability can support the diagnosis.

Several theories have been advanced to explain the relationship between HLA-B27 and the spectrum of disease observed. The arthritogenic peptide theory suggests that the presentation of an unknown peptide(s), perhaps of bacterial origin, activates cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the context of HLA-B27. Other theories propose that HLA-B27 molecules on antigen-presenting cells can either directly activate natural killer and T cells even in the absence of antigen or can induce a proinflammatory environment. Similarly, HLA-B27 expression on intestinal epithelium may interact with the gut microbiome to favor inflammation. Finally, tissue-specific chronic inflammation triggered by bacterial or mechanical stress may underlie a more autoinflammatory rather than autoimmune role for HLA-B27.

Other genes that have been identified as risk factors for spondyloarthritis include those associated with the TNF receptor signaling pathway as well as IL-1α and IL-23 receptor polymorphisms.

Environmental Factors

Considerable interest has focused on the role of the microbiome, particularly because gut inflammation is prevalent in many forms of spondyloarthritis. It is hypothesized that microbe-associated intestinal inflammation could cause loss of integrity of the bowel epithelium, permitting macrophage stimulation, increases in IL-23, and Th17 cell activation. However, specific causative pathogen exposure has not been identified except in some cases of reactive arthritis.

Classification

Spondyloarthritis is divided into five categories based on the predominant clinical features, although overlap of clinical features among these categories is common (Table 17):

- Ankylosing spondylitis: Spinal involvement is the defining feature.

- Psoriatic arthritis: Psoriasis co-occurs with spinal and/or peripheral arthritis.

- Inflammatory bowel disease–associated arthritis: Clinically apparent intestinal inflammation is present along with spinal and/or peripheral arthritis.

- Reactive arthritis: Inflammatory synovitis (primarily peripheral) occurs following specific gastrointestinal or genitourinary infections.

- Undifferentiated spondyloarthritis: Spondylitis occurs in the absence of diagnostic features (including radiographic changes) that would permit diagnosis of one of the other categories of disease.

Clinical features common to all forms of spondyloarthritis are back pain, enthesitis, and dactylitis. Back pain is often the presenting symptom for spondyloarthritis, although spondyloarthritis only accounts for about 5% of chronic low back pain. Unlike most forms of back pain, the pain in spondyloarthritis is inflammatory and typically occurs in patients under the age of 40 years. It is characterized by an insidious onset, duration of more than 3 months, presence at rest and at night (waking the patient), morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes, and improvement with exercise. Enthesitis, or inflammation at the site where a ligament or tendon attaches to bone, presents as pain and tenderness in areas such as the Achilles tendon (Figure 10). Dactylitis (“sausage digits”) is a diffuse fusiform swelling of the fingers or toes, consistent with tendon and ligament involvement beyond the points of insertion (Figure 11).

Although the categories listed here are extremely helpful in identifying and diagnosing disease, recently developed classification criteria emphasize the commonalities rather than the differences among the various forms of spondyloarthritis (for example, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society [ASAS] criteria for peripheral and axial disease). Such criteria may permit diagnosis and treatment at an earlier stage of disease before the unique features of the condition become well defined.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Psoriatic Arthritis

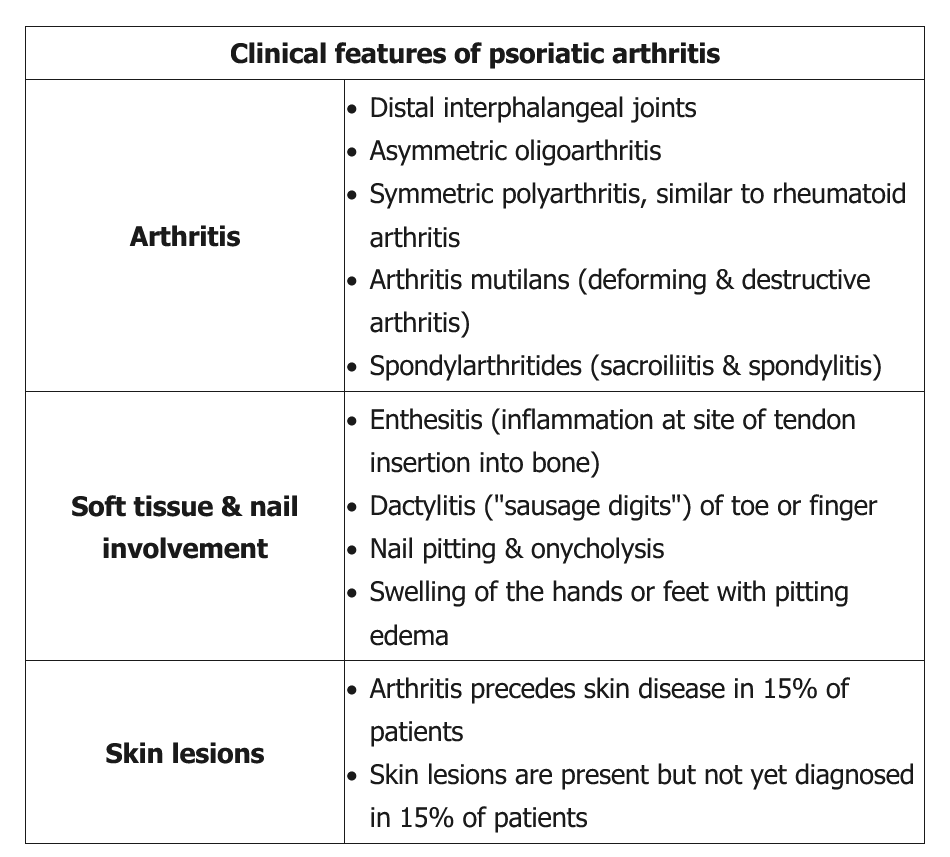

Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory joint disease associated with psoriasis. Estimates of the frequency of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis vary from 7% to 42%. Men and women are equally affected, and the usual age of onset is between 30 to 50 years. Psoriasis precedes or co-occurs with arthritis symptoms in about 90% of patients with psoriatic arthritis; less commonly, the rash may follow the arthritis, with a latency period as long as a decade. Skin involvement may be subtle, involving only areas such as the umbilicus, perineum, or gluteal cleft. There is no correlation between the extent of skin involvement and the severity of joint symptoms. In addition to skin lesions, nail pitting and onychodystrophy are seen; nail involvement is a risk factor for developing joint disease, particularly of the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 12).

Five clinical subtypes of psoriatic arthritis, which may overlap, are recognized as follows: symmetric polyarthritis; asymmetric oligoarthritis; distal interphalangeal–predominant disease; spondyloarthritis; and arthritis mutilans. Arthritis mutilans represents the rare end stage of progressive, destructive arthritis in the small joints of the hands. It results in subluxation, ligamentous laxity, and telescope-like retraction of the fingers. Additional joints usually become involved over time.

Enthesitis, tenosynovitis, and dactylitis often occur. Common locations for enthesitis include the Achilles tendon (see Figure 10), the calcaneal insertion of the plantar fascia, and ligamentous insertions into the pelvic bones. Dactylitis typically involves one or two digits; the feet are more commonly affected than the hands (see Figure 11).

Marked thickening of the distal right Achilles tendon and Achilles insertion on the calcaneus as the result of chronic Achilles tendinitis in a patient with psoriatic arthritis (normal contralateral Achilles insertion).

Marked thickening of the distal right Achilles tendon and Achilles insertion on the calcaneus as the result of chronic Achilles tendinitis in a patient with psoriatic arthritis (normal contralateral Achilles insertion).

Diffuse swelling of the first and second toes of the left foot due to dactylitis in a patient with psoriatic arthritis resulting in a “sausage digit” appearance.

Diffuse swelling of the first and second toes of the left foot due to dactylitis in a patient with psoriatic arthritis resulting in a “sausage digit” appearance.

The enthesis is a complex structure at the site of insertion of a tendon or ligament onto the bone. Inflammation of the enthesis (enthesitis) is highly suggestive of spondyloarthritis. When enthesitis is particularly severe, the inflammation may extend along the associated tendon and local ligaments, resulting in dactylitis (“sausage digits”). This patient has dactylitis, with diffuse inflammatory swelling of multiple digits, making spondyloarthritis the likely cause of this patient's presentation.

Features particularly characteristic of psoriatic arthritis include asymmetric distribution, distal interphalangeal joint involvement, osteolysis leading to pencil-in-cup deformity (Figure 14), and proliferative new bone formation along the shaft of metacarpal or metatarsal bones. There are no characteristic findings of reactive arthritis on plain radiographs.

Radiograph showing pencil-in-cup deformity of the fifth metatarsal joint and ankylosis of the fourth metatarsal joint in a patient with psoriatic arthritis.

Radiograph showing pencil-in-cup deformity of the fifth metatarsal joint and ankylosis of the fourth metatarsal joint in a patient with psoriatic arthritis.

Hand x-rays can reveal erosive changes with new bone formation, lysis of the terminal phalanges, joint destruction, "pencil-in-cup" appearance, and joint lysis with ankylosis.

Hand x-rays can reveal erosive changes with new bone formation, lysis of the terminal phalanges, joint destruction, "pencil-in-cup" appearance, and joint lysis with ankylosis.

Symptomatic and radiographic spine involvement is unusual at disease onset but increased over long-term follow-up, particularly in the cervical spine. The presence of sacroiliitis is associated with an increased likelihood for HLA-B27 positivity. In contrast to the almost universally bilateral sacroiliitis of ankylosing spondylitis, sacroiliitis is not always present in psoriatic arthritis and is more likely to be unilateral. Extra-articular manifestations are listed in Table 17.

Poor prognostic factors in psoriatic arthritis include the presence of polyarticular or erosive disease at the time of diagnosis. Patients additionally have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease–Associated Arthritis

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, may be associated with inflammatory arthritis in 6% to 46% of patients. Onset of arthritis may occur at any time in the course of the bowel disease.

IBD–associated arthritis occurs in three patterns:

- Sacroiliitis/spondylitis: occurs in up to 26% of patients; 50% to 75% are positive for HLA-B27; men are more frequently affected than women; radiographic abnormalities of the sacroiliac joints may be seen in the absence of symptoms.

- Acute polyarticular peripheral arthritis: self-limited; affects 5% of patients and occurs early in the course of IBD; the presence of arthritis is not as highly associated with HLA-B27 as in axial disease; the knee is most frequently involved; flares of joint symptoms may parallel exacerbations of bowel disease, but 90% resolve within 6 months.

- Chronic polyarticular peripheral arthritis: affects less than 5% of patients; men and women are equally affected; the presence of arthritis is not as highly associated with HLA-B27 as in axial disease; the metacarpophalangeal joints, knees, ankles, elbows, shoulders, wrists, proximal interphalangeal, and metatarsophalangeal joints may be affected; flares of arthritis may recur repeatedly over years and last for months, but joint symptoms are unrelated to bowel disease activity.

See Table 17 for information on extra-articular manifestations.

Reactive Arthritis

Reactive arthritis is a rare cause of inflammatory arthritis that can occur following specific genitourinary and gastrointestinal infections, including Chlamydia trachomatis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in the urethra and Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia in the intestine. Reactive arthritis occurs following 2% to 33% of cases of bacterial dysentery, with a higher incidence reported after single source outbreaks. About 90% of Yersinia-related cases occur in patients who are HLA-B27 positive, whereas only 30% to 50% of patients with reactive arthritis associated with other infectious agents are HLA-B27 positive.

Symptoms of inflammatory arthritis typically appear 2 to 3 weeks postinfection. Arthritis is asymmetric and may be monoarticular or oligoarticular; joints commonly affected include the knee, ankle, and wrist. Enthesitis is especially common; Achilles tendinitis and plantar fasciitis occur in up to 90% of cases. Dactylitis can also occur. The spine and sacroiliac joints are less commonly involved. In about half of patients, symptoms self-resolve within 6 months; most other cases self-resolve within 1 year, with a small proportion of cases converting to chronic disease. Extra-articular manifestations are described in Table 17. A subset of patients may demonstrate the “complete triad” of conjunctivitis, arthritis, and urethritis.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Studies

Spondyloarthritis is considered seronegative because rheumatoid factor and other autoantibodies are typically absent. HLA-B27 is present in many patients, particularly those with ankylosing spondylitis and spinal involvement; however, it cannot independently confirm or exclude a diagnosis. With active disease, evidence of systemic inflammation may be diagnostically helpful, including elevations of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein as well as normochromic, normocytic anemia. Each of these findings, however, is nonspecific and may be normal even in the presence of active disease. Several other laboratory findings are suggestive of the underlying disorder but are of limited utility diagnostically. Elevated IgA levels have been reported in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, consistent with increased mucosal immune activity. Serum alkaline phosphatase may be elevated in ankylosing spondylitis. Serum urate levels may be high in psoriatic arthritis, and these patients are at increased risk for co-occurrence of gout. Synovial fluid may show an elevated leukocyte count with a predominance of neutrophils.

In cases of suspected reactive arthritis, stool and urine cultures, genital swabs, nucleic acid amplification testing, and rising serum antibody titers against the suspected causative organism can be helpful in establishing the diagnosis. Pathogens can generally not be cultured from joint fluid in these patients, and antecedent infection is verified in less than half of affected individuals.

Imaging Studies

Radiography of the sacroiliac joints is an essential part of the initial evaluation of patients being assessed for spondyloarthritis but may be normal early in the course of disease. Radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis includes pseudo-widening of the joints, erosions, sclerosis, and ankylosis. In the spine, bony proliferation between vertebral bodies can result in formation of syndesmophytes (bony bridges) that can lead to a “bamboo spine” appearance in 10% to 15% of affected patients with ankylosing spondylitis (Figure 13). Other changes in the spine include vertebral squaring, disk calcification, and vertebral and facet joint ankylosis. In psoriatic arthritis, the syndesmophytes are often described as less delicate, more “chunky,” patchy, and asymmetric compared with those associated with ankylosing spondylitis.

Plain radiography of peripheral joints may aid in the diagnosis of spondyloarthritis, particularly when erosive and proliferative changes are present concurrently. Bony proliferative changes at entheseal sites may be seen in any spondyloarthritis.

Although plain radiography remains the cornerstone of radiographic diagnosis in spondyloarthritis, MRI is increasingly recognized as a useful diagnostic and prognostic modality. MRI is more sensitive for detecting early spine and sacroiliac joint inflammation and may be indicated in the evaluation of suspected spondyloarthritis if plain radiographs are negative. MRI can also detect inflammatory changes even in the absence of bony lesions. For example, the presence of bone marrow edema, although nonspecific, can suggest active inflammation in the sacroiliac joints. MRI can also detect soft-tissue abnormalities (such as bursitis and enthesitis), erosions, sclerosis, and ankylosis.

In older patients, the diagnostic specificity of radiographic evaluation for spondyloarthritis may decline. Other conditions such as osteitis condensans ilii, osteoarthritis, degenerative disk disease, and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) may cause sclerotic changes of the sacroiliac joints and osteophytes that may be difficult to distinguish from the syndesmophytes of ankylosing spondylitis. In particular, DISH typically causes multilevel bridging osteophytes. In ankylosing spondylitis, however, the bony bridges tend to be thinner and more vertically oriented than those seen in DISH.

Management

General Considerations

Management goals in spondyloarthritis are to control pain and inflammation, preserve function, and prevent progressive structural damage, including spine and joint ankyloses (fusion). Patient education regarding the course, treatment, and prognosis of disease, as well as the importance of general health, avoiding smoking, and participating in regular exercise are critical components of the overall treatment program.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

NSAIDs are recommended as first-line treatment in ankylosing spondylitis and remain important in management throughout the course of disease. Patients with ankylosing spondylitis are more likely to respond to NSAIDs and to do so more rapidly and completely than patients with chronic low back pain from other causes. Several studies suggest that, in contrast to most forms of arthritis, continuous use of NSAIDs may help slow disease progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Oral glucocorticoids are not recommended, but intra-articular glucocorticoid injections, including in the sacroiliac joints, can help alleviate pain. Nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate have no efficacy in axial disease and limited efficacy in peripheral disease.

According to a 2019 treatment update (Figure 33), persistent symptoms during NSAID therapy is an indication to escalate treatment to TNF inhibitors. The efficacy of TNF inhibitors in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis has been demonstrated in numerous randomized controlled trials, which showed improvements in clinical, radiographic, and MRI outcomes. Routine serial spine radiography for monitoring, however, is not recommended. With the probable exception of etanercept, TNF-α inhibitors are also effective in treating ankylosing spondylitis–associated anterior uveitis.

Physical therapy is the most important nonpharmacologic intervention in ankylosing spondylitis. The goals of therapy include improving pain and stiffness, maintaining range of motion, and reducing disability; transition to an ongoing daily exercise program is optimal.

Total hip arthroplasty can be highly effective in reducing pain and restoring function in the management of progressive hip involvement and may be indicated at an earlier age than in patients with osteoarthritis.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Treatment choices in psoriatic arthritis take into account the extent of both skin and joint involvement. NSAIDs may be effective for mild joint disease. Methotrexate is the most commonly used DMARD for psoriatic arthritis. Although benefit can be demonstrated in control of skin disease and joint pain, methotrexate has not been shown to reduce progression of joint damage. Sulfasalazine and leflunomide can also improve joint symptoms. Apremilast is modestly effective for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

In more severe psoriatic arthritis, TNF-α inhibitors (infliximab) have been shown to have superior efficacy in the management of joint symptoms and to slow the progression of radiographic damage, including joint-space narrowing and erosions. In patients with psoriatic arthritis who have uncontrolled disease while taking methotrexate at a dose of 25 mg weekly, the addition of a TNF-α inhibitor is indicated.

The biologic agents ustekinumab (anti-IL-12/23 antibody) and secukinumab (anti-IL-17A antibody) have also been approved for treating both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and can improve dactylitis and enthesitis.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease–Associated Arthritis

Various pharmacologic agents may be useful in the treatment of both intestinal and peripheral arthritis related to Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, including sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, glucocorticoids, and the TNF-α inhibitors infliximab and adalimumab. NSAIDs can provide symptomatic relief of arthritis symptoms but may occasionally exacerbate IBD.

Adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, and infliximab are more effective than other TNF-α inhibitors in treating the combination of bowel and joint manifestations.

Reactive Arthritis

Treatment of the antecedent infection is indicated in patients with reactive arthritis who have an identifiable cause. However, most patients present postinfection, and antibiotics are not usually effective in treating the arthritis. Most patients have self-limited disease, and short-term use of daily NSAIDs often improves symptoms until the condition resolves. If relief is incomplete, intra-articular glucocorticoid injections and oral glucocorticoids can be used. If symptoms persist beyond 3 to 6 months, the use of DMARDs such as sulfasalazine, methotrexate, or TNF-α inhibitors may be necessary for symptom control and to prevent joint erosion. Therapy is discontinued 3 to 6 months following disease remission.