Schistosomiasis

- related: ID

- tags: #id

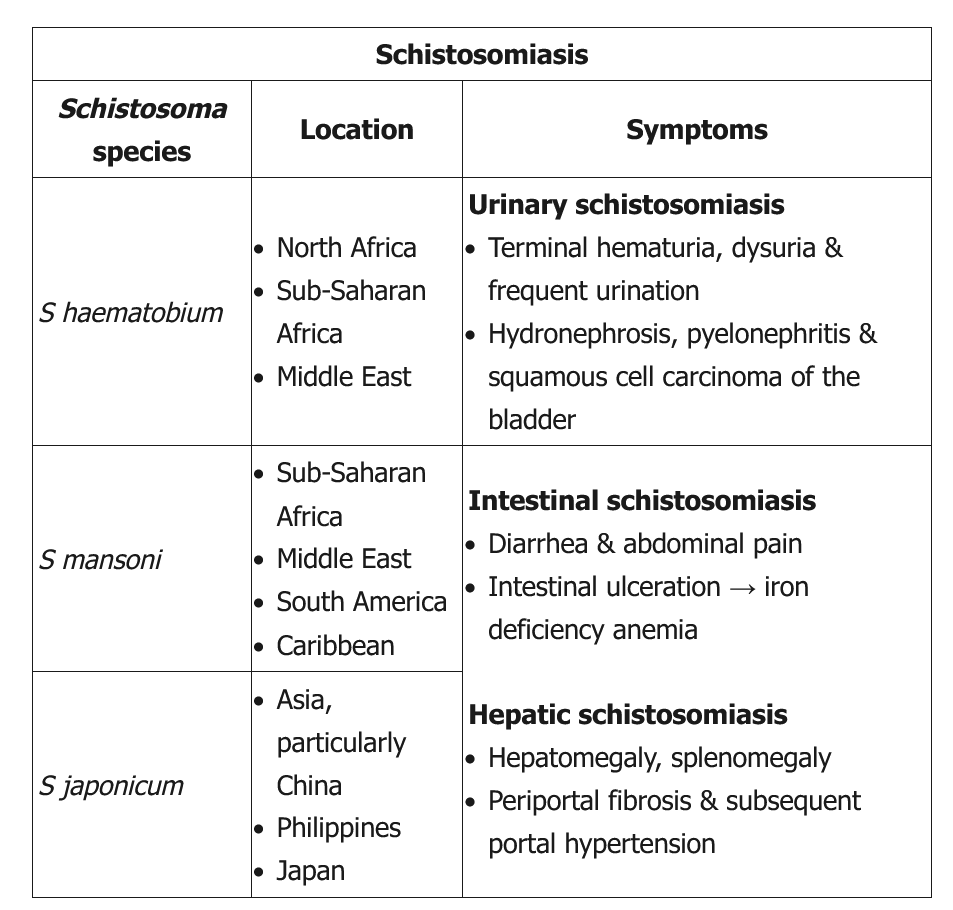

This young man with terminal hematuria (blood at the end of micturition) has a history of extensive travel to a schistosomiasis-endemic area; his laboratory studies are notable for eosinophilia, hematuria, and leukocyturia without bacteriuria or glomerular casts. These findings are consistent with Schistosoma haematobium infection. In contrast to acute schistosomiasis syndrome or Katayama fever (more frequent in travelers with no immunity), chronic schistosomiasis most commonly occurs in patients who live in endemic areas or have frequent exposure to contaminated fresh water. Symptoms depend on the infection site (Table). Genitourinary schistosomiasis (due to S haematobium) can present with dysuria, urinary frequency, bladder outlet obstruction, or terminal hematuria.

Disease largely occurs due to a granulomatous immune reaction to the deposits of schistosomal eggs in the tissues. In patients from endemic areas, diagnosis is made by identifying and quantifying eggs in the urine or stool; in travelers, serology is best due to lighter disease burden and higher test sensitivity. Chronic infection should be treated with praziquantel.

Acute onset of fevers, allergic-type symptoms (urticarial lesions, angioedema), and robust eosinophilia in the setting of a recent trip to sub-Saharan Africa with freshwater exposure is suggestive of acute schistosomiasis syndrome (Katayama fever). This is a systemic hypersensitivity reaction against schistosomal eggs and larvae, typically occurring 14-28 days after infection. Chest x-ray infiltrates may be present. Microscopic examination for schistosomiasis eggs and serologic testing may be negative in acute schistosomiasis. The episode is usually self-limiting (days to weeks), and management is with corticosteroids during the acute phase followed by antihelminthic therapy (eg, praziquantel) to prevent long-term sequelae of helminth infection (eg, hydronephrosis, bladder squamous cell carcinoma).