HIV-AIDS

- related: ID

- tags: #id

HIV is a retrovirus that infects CD4 lymphocytes, among other cell types. Depletion of CD4 T-helper cells results in impairment of cell-mediated immunity and increasing risk for opportunistic infections. This chapter will focus on HIV-1. Infection with HIV-2 primarily occurs in parts of Africa and remains rare in the United States; HIV-2 generally is a less progressive disease with less immunocompromise and lower risk of opportunistic infections. Current testing for HIV infection detects HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies (see Screening and Diagnosis).

Epidemiology and Prevention

HIV infection remains a significant global health concern despite being a treatable disease. Many persons living with HIV infection are not aware of their status because they have never been tested; others have been diagnosed but are not receiving care. Those with undiagnosed or untreated infection are responsible for most new infections. Diagnosis and successful treatment are crucial for personal and public health.

HIV transmission occurs through sexual contact or exposure to other body fluids (Table 62). Reducing transmission can be accomplished by using barrier methods, such as condoms during sexual contact, and through clean syringe services programs (needle exchange programs) for injection drug users. Universal blood donor testing has all but eliminated infection through blood transfusion in the United States, with current risk estimated to be one in 2 million.

HIV treatment has extraordinary potential to reduce new infections in addition to benefiting the treated person. Successful treatment is associated with significant reductions in HIV transmission. Although reducing viral load to an undetectable level in blood does not prove absence of virus in semen or vaginal fluid, the rate of transmission from a sexual partner with undetectable blood viral load has been demonstrated to be close to zero, at a level the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) called “effectively no risk” in a September 2017 statement, leading to the slogan “Undetectable = Untransmittable” (“U=U”). Also termed “treatment as prevention” (TasP), maintaining an HIV RNA level less than 200 copies/mL with antiretroviral therapy for at least 6 months prevents HIV transmission to sexual partners. Transmission is possible during periods of poor adherence or treatment interruption. TasP does not prevent acquisition or transmission of other sexually transmitted infections. In what is known as the “treatment cascade,” steps of medical care necessary to achieve successful viral suppression consist of testing and diagnosing infected persons, linking them to health care for counseling and treatment, keeping them in a treatment program, and ensuring antiretroviral and other treatment adherence. Each step along this continuum of care is a potential obstacle to successful management of HIV on a personal and public health level. Even high-income countries, such as the United States, have poor rates of retention in care and adherence to medication. One study estimated that the undiagnosed and not-in-care groups with HIV infection were responsible for 91.5% of HIV transmissions in the United States in 2009.

In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) launched its “90-90-90” program of ambitious goals for reducing new HIV infection worldwide. These goals include that by 2020, 90% of HIV-infected persons will have been diagnosed, 90% of those diagnosed will be receiving treatment, and 90% of those receiving treatment will have successful viral suppression. Achieving such goals will require considerable resource commitment but, if achieved, will also dramatically reduce transmission and new HIV infections.

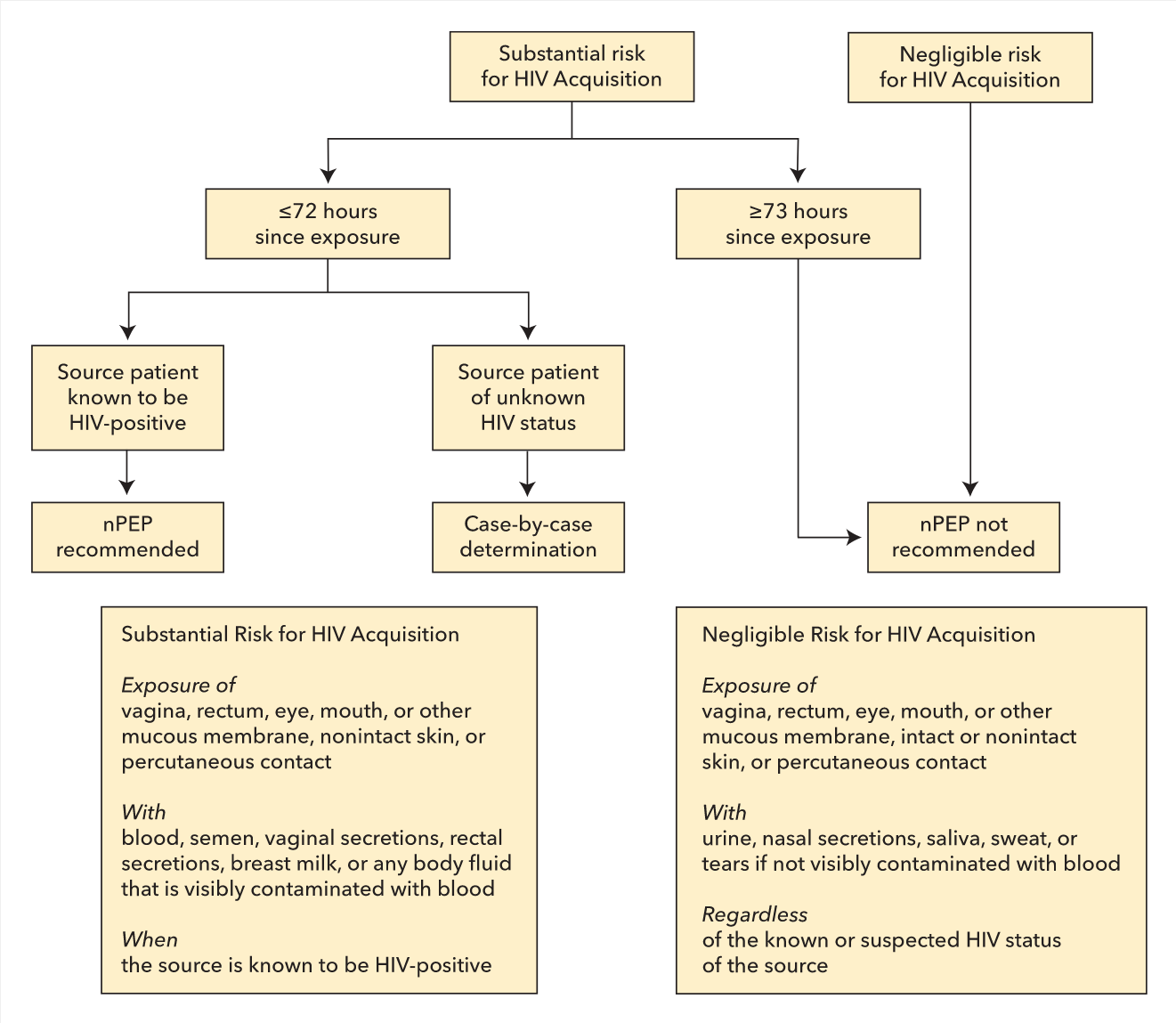

Postexposure prophylaxis antiretroviral therapy has been used successfully for many years in uninfected persons to prevent infection after occupational and nonoccupational HIV exposure. Prophylaxis should be started as soon as possible after exposure; it is not recommended if more than 72 hours have passed. A three-drug regimen is given for 4 weeks; the preferred regimen is tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine plus either raltegravir or dolutegravir. HIV testing of the exposed person should be conducted at baseline and at 4 to 6 weeks and 3 months after exposure. Figure 22 shows an algorithm for evaluation of possible HIV exposure. f the source patient was known to have an undetectable viral load in blood, the risk would be reduced but not eliminated.

Algorithm for evaluation and treatment of possible HIV exposure. nPEP = nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis.

Algorithm for evaluation and treatment of possible HIV exposure. nPEP = nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with antiretroviral medication is recommended in select persons at high risk for exposure to HIV to reduce the risk of infection. A two-drug combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine, taken once daily, is FDA approved for HIV PrEP; it has been shown to be effective in reducing infection in persons at high risk. Effectiveness is greater than 90% in those with proven adherence. Additionally, once-daily tenofovir alafenamide and emtricitabine is approved for HIV PrEP, excluding in women who have receptive vaginal sex (effectiveness has not been established in this population). The US Preventive Services Task Force has identified specific groups of persons at high risk of HIV infection, including men who have sex with men (MSM), persons at risk through heterosexual contact, and persons who inject drugs. Persons at very high risk for HIV infection in whom PrEP is recommended have one or more of the following characteristics: a serodiscordant sex partner; inconsistent use of condoms during receptive or insertive anal sex (MSM) or with a heterosexual partner whose HIV status is unknown or is at high risk; syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia infection within the past 6 months for MSM; or syphilis or gonorrhea infection within the past 6 months for heterosexual women. An additional indication for PrEP is the shared use of drug injection equipment. PrEP is also indicated in persons who engage in transactional sex or who are trafficked for sex work, men who have sex with men and women, and transgender persons if any high-risk sexual characteristics or behaviors are present. Transgender women are at especially high risk of infection. Patients should also be counseled on the need to continue barrier precautions, on medication toxicity, and on continued risk for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Testing should be performed for HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), kidney function, and pregnancy before PrEP initiation; monitoring for HIV, other STIs, and pregnancy every 3 months and performing kidney function assessment every 6 months are also recommended during PrEP therapy. Persons taking PrEP who test positive for HIV should have a third drug (either ritonavir-boosted darunavir or dolutegravir) added to the two-drug PrEP regimen pending results of HIV RNA and viral resistance testing. The evidence is conflicting concerning potentially increased high-risk behavior and incidence of other STIs in PrEP users during therapy. PrEP has also been calculated to have favorable cost effectiveness, well below that for other accepted preventive health measures.

Pathophysiology and Natural History

Acute Retroviral Syndrome

Most persons with acute HIV infection are symptomatic; however, because symptoms are nonspecific and self-limited, most acute infections are not diagnosed accurately. The frequency of signs and symptoms at presentation is shown in Table 63. The differential diagnosis includes Epstein-Barr virus infection, cytomegalovirus infection, and secondary syphilis. During symptomatic acute infection, HIV antibody may not yet be detectable, and diagnosis depends on demonstration of p24 antigen or HIV RNA. Currently recommended HIV testing includes p24 antigen testing as part of the initial evaluation (see Screening and Diagnosis). Persons with acute HIV infection should be immediately linked to care for prompt initiation of treatment.

Chronic HIV Infection and AIDS

Patients with chronic HIV infection may present with opportunistic infections, especially when CD4 counts are less than 200/µL, meeting the definition for AIDS (see Opportunistic Infections). Even before progression to AIDS, patients with HIV infection may present with recurrent or severe episodes of infections that do not qualify as opportunistic, such as bacterial pneumonia, herpes zoster, herpes simplex virus, or vaginal candidiasis. Other symptoms can result from chronic HIV infection itself, including lymphadenopathy, fever, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss, chronic diarrhea, and various oral and skin conditions (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology). HIV should also be considered in patients with unexplained cytopenias or nephropathy.

Screening and Diagnosis

Although any of the presenting symptoms described previously should prompt HIV testing, testing only symptomatic persons neglects numerous persons who are infected. Thus, the CDC, American College of Physicians, Infectious Diseases Society of America, and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend universal screening for HIV in all adults at least once. The USPSTF suggests those at higher risk (injection drug users and their sexual partners, people who exchange sex for money or drugs, sexual partners of HIV-infected persons, and those with more than one sexual partner since their most recent HIV test) should undergo repeat HIV testing at least annually. In 2017, the CDC reaffirmed its support for this recommendation but noted that clinicians can consider the potential benefits of more frequent HIV screening (for example, every 3 or 6 months) for some asymptomatic sexually active men who have sex with men based on their individual risk factors, local HIV epidemiology, and local policies.

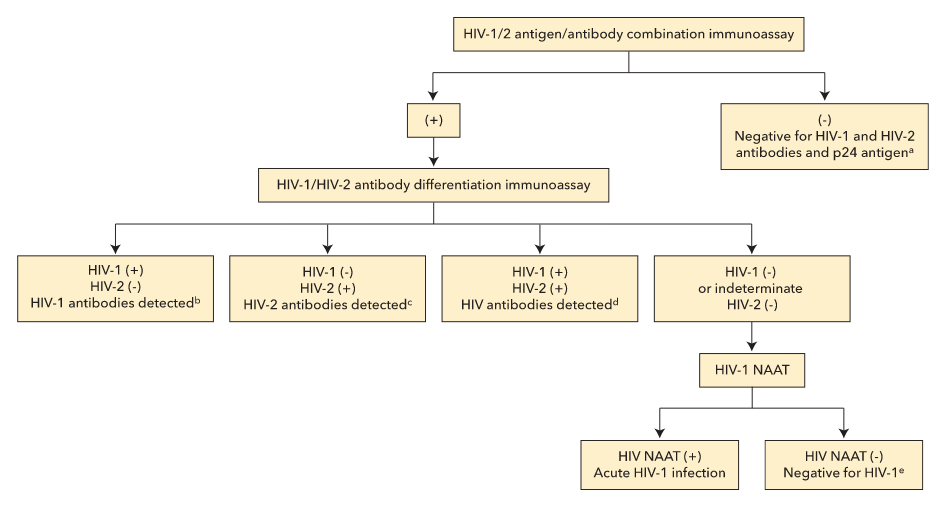

Current (fourth generation) HIV testing uses a combination assay for HIV antibody and HIV p24 antigen, which detects acute infection at least 1 week earlier than older assays. A positive result on the combination assay leads to testing with an HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay, which, if positive, confirms infection. Specimens that test positive on the initial combination assay but negative for HIV antibody are tested for HIV RNA by nucleic acid amplification testing; if positive, acute HIV infection is confirmed (Figure 23). Although the initial combination assay has a 99.6% specificity, testing in low prevalence populations (such as general screening) can still result in false positives, so waiting for the results of the confirmatory antibody differentiation immunoassay and nucleic acid amplification testing is important for a definitive diagnosis.

CDC-recommended algorithm for laboratory HIV testing. NAAT = nucleic acid amplification test. (+) indicates reactive test result. (−) indicates nonreactive test result.

a. No evidence of HIV infection. b. HIV-1 infection: acute HIV infection window before antibody development c. HIV-2 infection. d. HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection. e. HIV-1/2 antigen/antibody combination immunoassay result was a false positive.

Initiation of Care

Initial Evaluation and Laboratory Testing

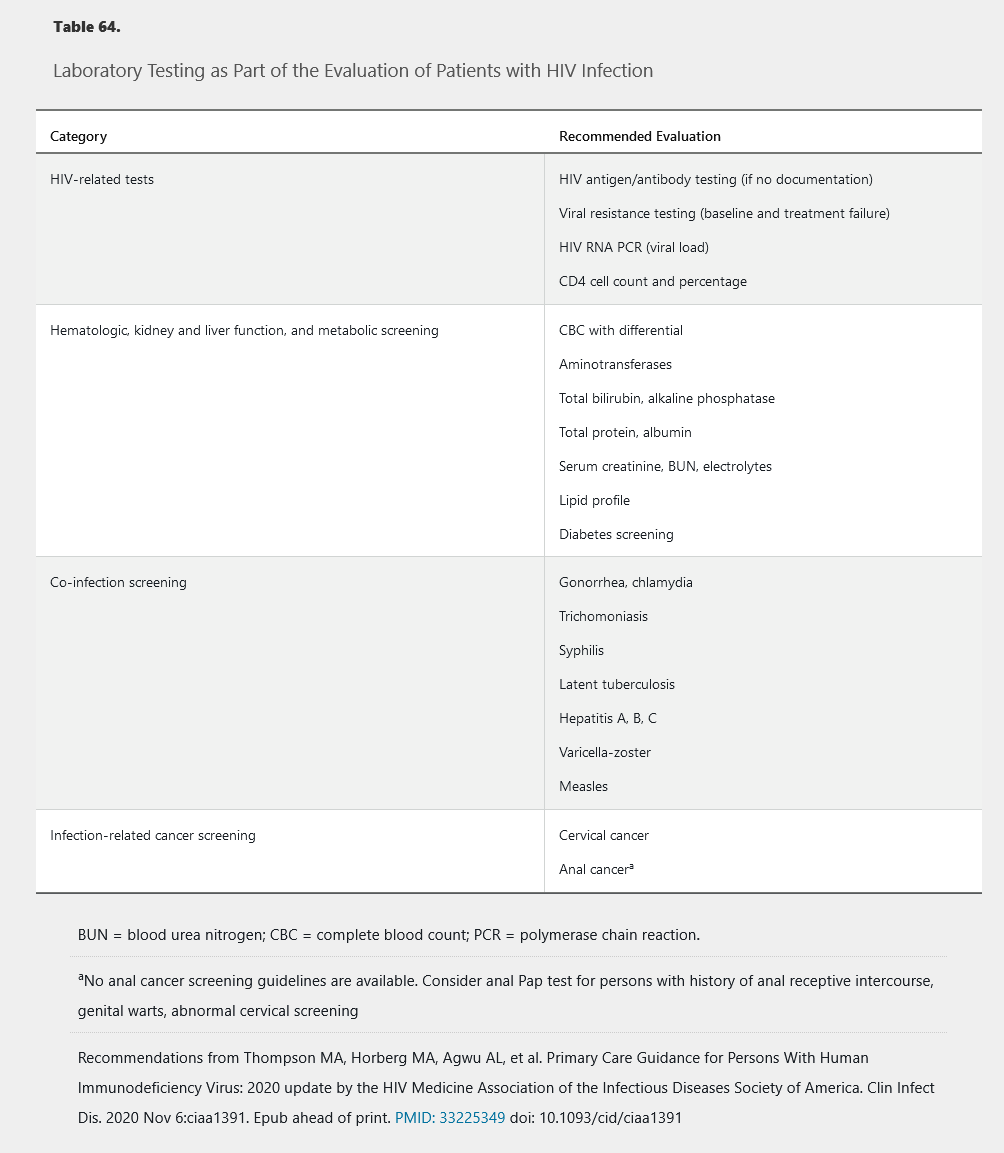

All persons who test positive for HIV should be immediately referred to a health care provider with HIV infection management expertise. Initial evaluation should include complete history (including social and sexual) and examination for signs and symptoms of opportunistic infection or other complications. Patient education and counseling should include information on transmission and prevention. Initial laboratory tests include baseline organ function and evaluation for other infections with higher prevalence in persons with HIV (Table 64). A baseline CD4 cell count guides opportunistic infection prophylaxis, and a baseline viral load supports monitoring antiretroviral therapy effectiveness (see Management of HIV Infection).

Immunizations and Prophylaxis for Opportunistic Infections

Numerous immunizations are recommended for all persons with HIV, starting with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines, respectively, at least 8 weeks apart; a 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine booster is also recommended after 5 years. Patients who are not already immune or infected with HBV should receive the hepatitis B vaccine series. Influenza, tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis, hepatitis A, and human papillomavirus vaccinations are indicated as for the general population. Measles-mumps-rubella and varicella vaccines can be given as long as the CD4 cell count is greater than 200/µL. The recombinant zoster vaccine should be given to individuals 50 years and older with CD4 cell count greater than 200/µL. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that all persons with HIV infection be vaccinated for meningococcal disease with the quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine, including boosters every 5 years.

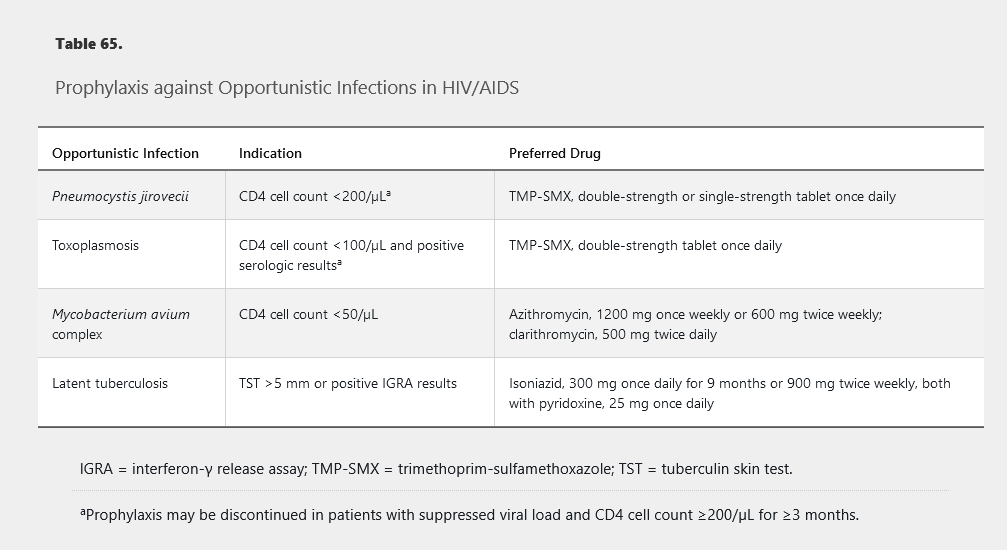

Prophylaxis for opportunistic infections depends on the patient's CD4 cell count (Table 65). Before beginning prophylaxis, active infection should be ruled out clinically and with any indicated testing to avoid undertreatment and selection for resistance, especially for tuberculosis and disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex.

Complications of HIV Infection in the Antiretroviral Therapy Era

Metabolic, Kidney, and Liver Disorders

As HIV has become a treatable illness and persons with HIV age, metabolic disorders and specific organ diseases have become increasingly significant. HIV infection itself may be associated with manifestations of accelerated aging, and neurocognitive impairment can be exacerbated by HIV. Age-associated comorbidities and declines in kidney and liver function can also complicate management through drug interactions and increased toxicity.

HIV infection itself and some antiretrovirals affect lipids and can worsen hyperlipidemia; this is especially true for boosted protease inhibitor–based regimens, which can also worsen insulin resistance. Fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1c and lipid levels should be checked at baseline and 3 months after initiating or changing antiretrovirals; hemoglobin A1c should not be used for the diagnosis of diabetes in those taking antiretroviral therapy.

Chronic kidney disease is increasingly common in HIV infection, although, with effective antiretroviral therapy, it is less often attributed to HIV nephropathy. It is recommended that kidney function be assessed at least every 6 months in patients with HIV. Tenofovir, a very commonly used nucleoside analogue, is associated with risk for tubular nephrotoxicity, which usually manifests as proteinuria. Patients using a regimen containing tenofovir should undergo urinalysis or quantitative measurement of urine protein twice per year.

Bone mineral density is reduced in HIV, and tenofovir is also associated with possible worsening of bone density. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scanning is recommended in men older than 50 years, postmenopausal women, patients with a history of fragility fracture, those with chronic glucocorticoid use, and those at high risk for falls. A newer prodrug of tenofovir, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), achieves high intracellular levels of active drug with much lower dosing and lower systemic levels compared with the older formulation, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). Compared with TDF, TAF has equal antiviral efficacy with reduced kidney and bone toxicity and should be used preferentially over TDF in patients with or at risk for bone or kidney disease.

Liver disease is also increased in HIV infection, often because of coinfection with hepatitis B or C virus. All patients with HIV should be screened for hepatitis B and C viruses. Patients should be immunized if they are HBV negative. If coinfected with HIV and HBV, patients should receive treatment with a tenofovir (either TDF or TAF) plus emtricitabine or lamivudine-based regimen, which treats both viruses. Patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus should be given a course of curative direct-acting antiviral treatment, although attention must be paid to drug interactions between the antiviral regimens (see MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology and Hepatology).

Cardiovascular Disease

Rates of cardiovascular disease, including myocardial infarction and stroke, are higher in persons with HIV infection; this association remains after correction for increased risk factors such as smoking. Some of the increase may result from hyperlipidemia, but evidence indicates that the increase partially results from HIV infection being a chronic inflammatory state. It is clear that patients with untreated HIV infection have a higher risk of cardiovascular events compared with patients taking effective antiretroviral therapy, regardless of any worsening of lipid levels from the antiretroviral therapy. Attention to traditional risk factors such as smoking, lipid levels, and hypertension is crucial in patients with HIV, as is use of statin therapy (with attention to drug interactions between some statins and some antiretrovirals) based on current risk calculations. An international multicenter trial is addressing whether patients with HIV should be treated with statins even with a 10-year risk less than 7.5%.

Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a disorder associated either with worsening of a pre-existing infectious process (paradoxical IRIS) or with revelation of a previously unrecognized pre-existing infection (unmasking IRIS) (return of robust immune response during treatment unmasks preexisting infection). It has also been reported with noninfectious complications, such as lymphoma. IRIS usually occurs within a few months of initiating effective antiretroviral therapy in patients with low pretreatment CD4 cell counts (<100/µL). Management of IRIS includes continuing antiretroviral therapy while treating the opportunistic infection. In select patients, NSAIDs or glucocorticoids may be useful in mitigating inflammatory symptoms. Antiretrovirals should not be stopped when IRIS occurs. Therapy should be continued while providing treatment for the newly diagnosed infection. Prednisone can be added if IRIS is life threatening or involves the pericardium or central nervous system.

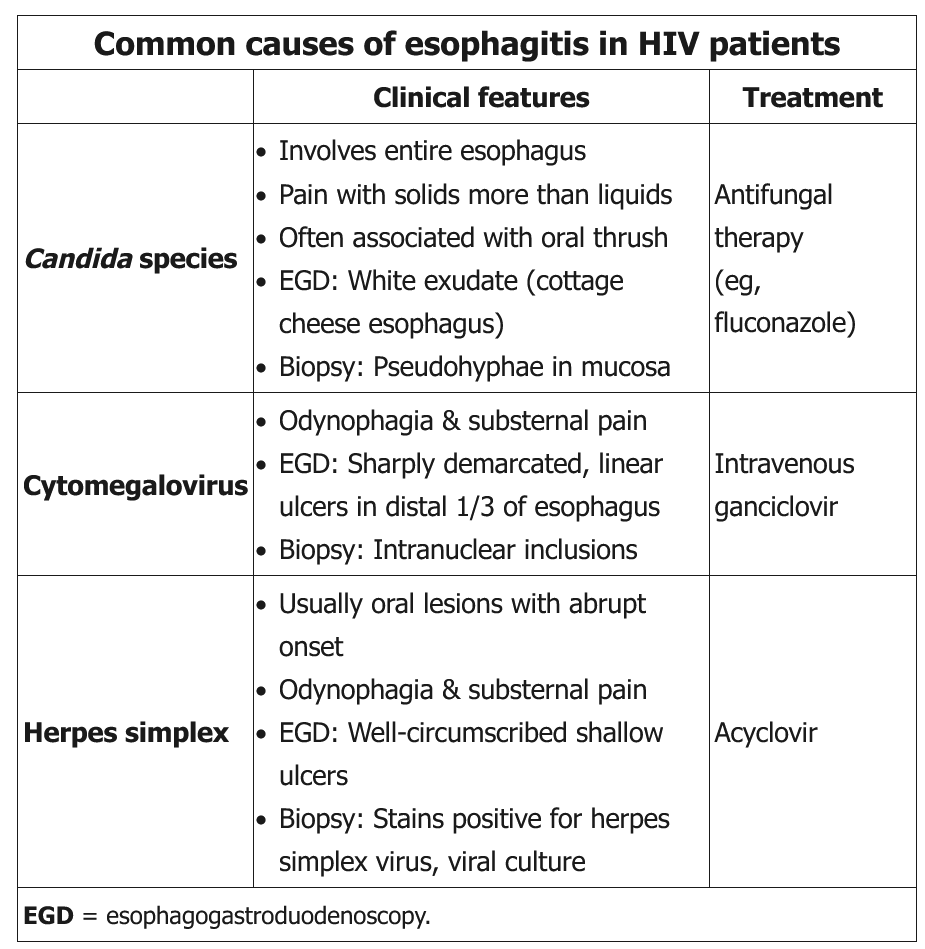

HIV Esophagitis

This patient with HIV/AIDS has odynophagia, raising concern for infectious esophagitis, particularly given his CD4 count <100 cells/mm3 and noncompliance with antiretroviral therapy. Candida albicans, the most common cause of infectious esophagitis in immunosuppressed patients, typically presents with moderate odynophagia, dysphagia, and concurrent oral thrush. Patients with these classic features may be given an empiric trial of systemic antifungals (eg, oral fluconazole).

However, the presence of severe odynophagia without evidence of thrush favors ulcerative esophagitis; retrosternal pain and fevers can also occur, as seen in this patient. Ulcerative esophagitis is commonly due to viral infections. Herpes simplex virus esophagitis, which often occurs with concurrent herpetic outbreaks elsewhere (eg, herpes labialis), can lead to bleeding and tracheoesophageal fistula formation. Cytomegalovirus esophagitis often occurs with concurrent retinitis, which can lead to blindness. As a result, severe odynophagia, fevers, and the absence of classic candidal esophagitis symptoms should prompt endoscopy with biopsy and culture rather than a trial of empiric fluconazole to ensure correct diagnosis (Choice C). Endoscopy would also help identify the 18% of cases of Candida esophagitis not associated with thrush as well as exclude malignancy as the cause of this patient's presentation.

Opportunistic Infections

Mucocutaneous Candida infections can occur in HIV-infected patients at relatively preserved CD4 cell counts. HIV-infected patients do not usually develop invasive Candida infection unless they have other risk factors, such as neutropenia. Oral candidiasis usually presents as thrush, with mucosal whitish plaques, and can be treated topically (for example, with clotrimazole troches) or with a short course of oral fluconazole. Swallowing symptoms suggest esophageal disease, which requires systemic treatment, such as fluconazole, for a longer course; a lack of treatment response is an indication for endoscopy.

The preferred treatment is oral fluconazole regardless if the disease is isolated to the oral cavity or extends into the esophagus; however, esophageal involvement warrants a more prolonged course (14-21 days rather than 7-14 days). Clinical response is usually apparent within a few days.

Topical agents such as nystatin are less effective than systemic fluconazole for oropharyngeal candidiasis and are especially ineffective for esophageal disease.

Reactivation of latent tuberculosis is also significantly increased in HIV infection, even without a decreased CD4 cell count. Tuberculosis is also more likely to present in extrapulmonary sites or with an atypical chest radiograph. Tuberculosis treatment in HIV must consider interactions of rifamycins with many antiretrovirals.

He had an indeterminate result on interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) because of an inadequate response to the positive control, which was the result of immunocompromise at the time of presentation; additionally, the results of IGRA testing are a poor indicator of active tuberculosis infection. He should begin four-drug antituberculous therapy while results of culture and susceptibility testing are pending. Nucleic acid amplification testing of the specimen may give information on the identification of the organisms and even the possibility of rifamycin resistance. Initial empiric treatment for tuberculosis should include a rifamycin as one of the four drugs, but rifabutin is often preferred over rifampin in patients with HIV because of fewer drug-drug interactions between rifabutin and antiretrovirals, including dolutegravir.

Infections with other opportunistic organisms usually occur at CD4 cell counts less than 200/µL. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia usually presents as a subacute illness with fever, dyspnea, and dry cough in a patient with a CD4 cell count less than 200/µL who is not receiving prophylaxis. Chest radiographs most often show bilateral interstitial infiltrates; cavitation or pleural effusion is unusual and suggests another diagnosis. A normal chest radiograph does not exclude the diagnosis, and chest CT is more sensitive, demonstrating patchy “ground-glass” opacities. Normal lactate dehydrogenase levels and stable exercise oxygen saturation have a high negative predictive value, but elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels and oxygen desaturation with exercise are nonspecific. Diagnosis depends on demonstration of causative organisms and often requires bronchoscopy. The treatment of choice is high-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; patients who are hypoxic at presentation should be given adjunctive glucocorticoids to prevent the worsening that may accompany initiation of treatment.

Cryptococcus infection usually presents as subacute meningitis with headache, mental status changes, and fever. Because it often involves the basilar area, cranial nerve deficits may also be seen. The diagnosis can be made most swiftly by antigen testing of cerebrospinal fluid and blood. Management includes antifungal therapy and attention to increased intracranial pressure, which is usually responsible for the morbidity and mortality associated with cryptococcal meningitis (see Fungal Infections).

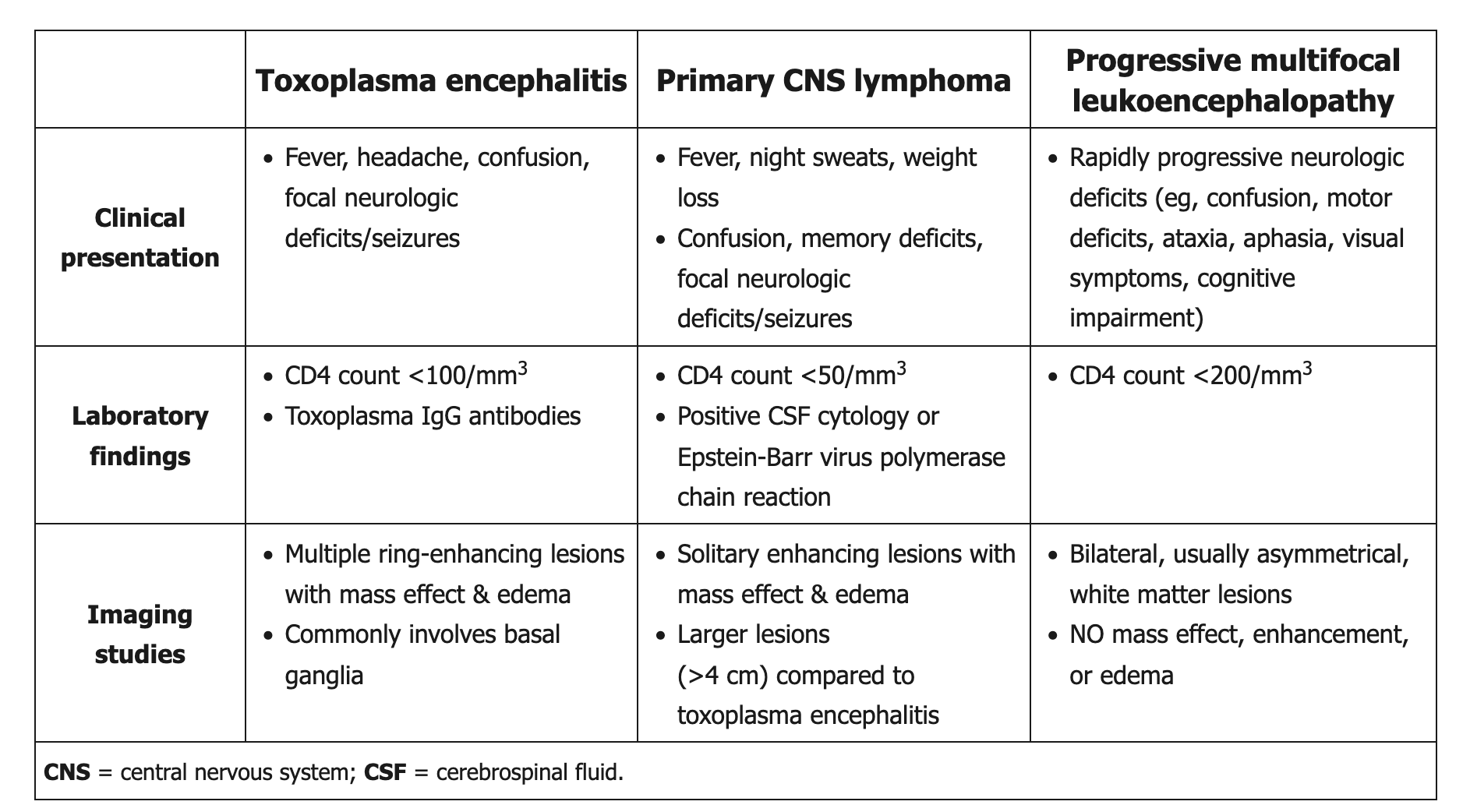

Toxoplasma gondii infection in AIDS usually presents in patients with CD4 cell counts less than 100/µL. Because it is a reactivation disease, patients are usually serology positive. Clinical presentation includes headache, fever, and focal neurologic deficits. Imaging by CT or MRI (which is more sensitive) reveals multiple ring-enhancing lesions. The differential diagnosis includes primary central nervous system lymphoma, which most often appears as a single lesion on imaging, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, which is usually nonenhancing and without edema or mass effect. Diagnosis of central nervous system toxoplasmosis is usually presumptive based on presentation, imaging, and response to empiric treatment.

Mycobacterium avium complex infection usually presents as disseminated disease in patients with CD4 cell counts less than 50/µL; symptoms and signs include fever, sweats, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and cytopenias. Blood cultures for acid-fast bacilli will usually grow Mycobacterium avium complex, but it may also be found on lymph node or liver biopsy when necessary.

Cytomegalovirus most commonly presents with CD4 cell counts less than 50/µL. Cytomegalovirus retinitis, presenting with vision changes or floaters, is much more likely in AIDS than in other immunocompromised conditions, such as after transplantation. Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease is also common, most often as esophagitis or colitis.

Patients with AIDS are also more likely to develop certain malignancies, especially those related to viruses. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, especially primary central nervous system lymphoma related to Epstein-Barr virus, is significantly increased compared with age-matched controls. Kaposi sarcoma is caused by human herpes virus type 8 and presents as dark red, brown, or violaceous lesions of the skin or mucous membranes (Figure 24); human herpes virus type 8 can also cause primary effusion lymphoma and Castleman disease (giant lymph node hyperplasia). Human papillomavirus–related malignancies are significantly increased in HIV, including cervical and anal cancers, and regular guideline-based screening is important (see Table 64).

Kaposi sarcoma, presenting as firm purple nodules on the face and purple palatal nodules, is seen in a patient with AIDS.

Kaposi sarcoma, presenting as firm purple nodules on the face and purple palatal nodules, is seen in a patient with AIDS.

Management of HIV Infection

When to Initiate Treatment

All persons with HIV infection should begin antiretroviral therapy as soon as they are ready, regardless of CD4 cell count. Previous controversy over whether to start antiretroviral treatment in asymptomatic patients with normal CD4 cell counts has been resolved with demonstration of clear clinical benefit in a large prospective, randomized clinical trial.

Antiretroviral Regimens

Antiretroviral agents used in the United States are shown in Table 66. Standards for effective antiretroviral regimens include use of three drugs from two different classes, preferably combining two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors with an integrase strand transfer inhibitor. Preferred regimens also feature a high barrier to resistance, good tolerability and safety, and combination pills with once-daily dosing to facilitate adherence (Table 67).

Patients with or at risk for reduced kidney function or osteopenia should not be given TDF. Patients who are prescribed abacavir must first undergo testing to show they are HLA-B*5701 negative to reduce the risk of hypersensitivity. Many antiretrovirals have interactions with other drugs, and potential drug interactions must always be assessed when beginning HIV therapy or beginning any drug for someone already taking antiretroviral therapy. Such assessment is especially necessary when pharmacokinetic boosters (ritonavir or cobicistat) are used specifically to inhibit drug metabolism and raise levels of antiretrovirals.

Viral load levels and CD4 cell counts are monitored to ensure effectiveness and to assess for immune recovery. With optimal therapy, HIV RNA in blood should become and stay undetectable. CD4 cell counts will increase, although cell counts may take time to improve and may not show full recovery, especially in those who are older or who have other factors affecting lymphocytes. Patients taking antiretroviral therapy who are stable with a CD4 cell count of 500/µL or more for more than 2 years can stop T-cell monitoring as long as viral load remains undetectable.

Resistance Testing

Viral resistance testing should be performed at baseline to ensure selection of a fully active regimen and should be repeated if the viral load increases during antiretroviral treatment. The most common reason for breakthrough viremia is poor medication adherence. In general, plasma levels of HIV RNA must be greater than 500 copies/mL to provide enough virus for resistance testing. Viral resistance testing can be genotypic (looking for mutations associated with drug resistance) or phenotypic (assessing whether virus can replicate in the presence of the drug). Genotypic testing is faster and cheaper, but phenotypic testing may be better in the presence of multiple mutations or for drugs such as protease inhibitors in which the correlation of specific mutations and resistance is less straightforward. Genotypic testing is faster and less expensive because all that is necessary is sequencing of the respective genes for the patient's viral isolate. When significant resistance is not expected and information is needed more quickly, genotypic testing would be preferred over phenotypic testing. Resistance testing results are used to guide selection of a new regimen in the event resistant virus develops, but previous resistance testing results as well as previous regimens and responses must also be considered. Resistance testing may not be reliable if performed while the patient is not taking an antiretroviral regimen because resistance may not be detectable without the selective pressure of the antiretrovirals. Once selected for, previous mutations are generally archived in the viral population and may re-emerge even if resistance testing does not demonstrate the mutation. A regimen may also be switched because of adverse effects or to ease adherence or avoid drug interactions. Laboratory monitoring tests should be repeated 1 month after switching regimens to assess effectiveness and toxicity.

Management of Pregnant Patients with HIV Infection

The management of pregnant women with HIV does not significantly differ from the management of nonpregnant women. Initiating antiretroviral therapy is recommended as soon as possible in pregnant women with HIV who are not already being treated, and it is especially important that women already receiving HIV treatment who become pregnant continue treatment without interruption. Antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy benefits the woman and significantly reduces the risk of perinatal transmission of HIV to her baby. Previous concerns about teratogenicity of some antiretrovirals, including concerns about neural tube defects with efavirenz, have been allayed by data showing no difference in birth defect rates compared with the general population regardless of when therapy was started. Initial treatment regimen selection in pregnant women does not typically differ from nonpregnant women; however, elvitegravir-cobicistat is not recommended because levels are inadequate in the second and third trimesters, and bictegravir and TAF are not recommended until safety and pharmacokinetic data in pregnancy are available. The prevalence of neural tube defects in infants born to women who receive dolutegravir is 0.3%, compared with 0.1% in women not taking it. The benefits and risks of dolutegravir therapy should be discussed with patients to assist informed decision making. Dolutegravir may be used as an alternative antiretroviral drug for women of childbearing age who are sexually active and not using contraception; it may be used as a recommended option for those using effective contraception.