Bioterrorism

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Introduction

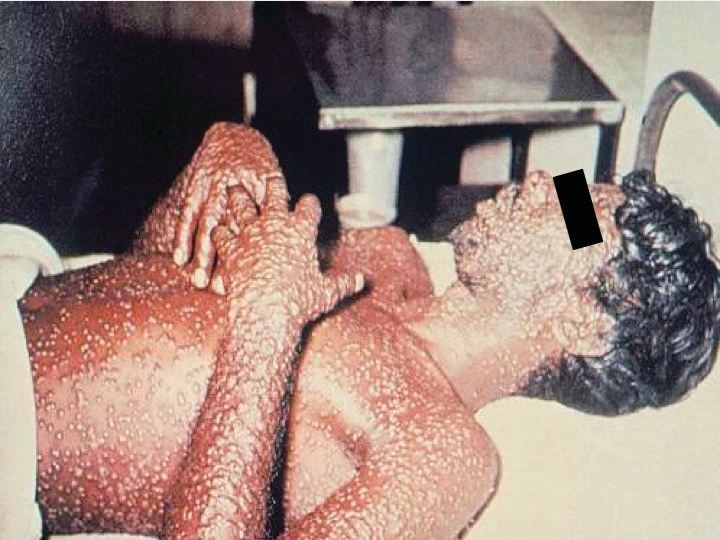

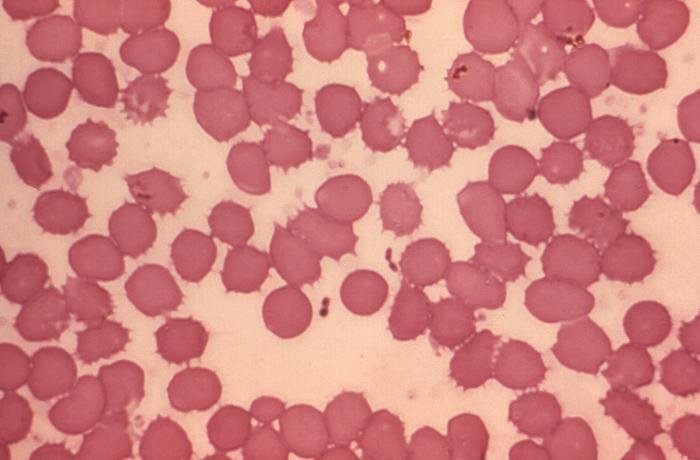

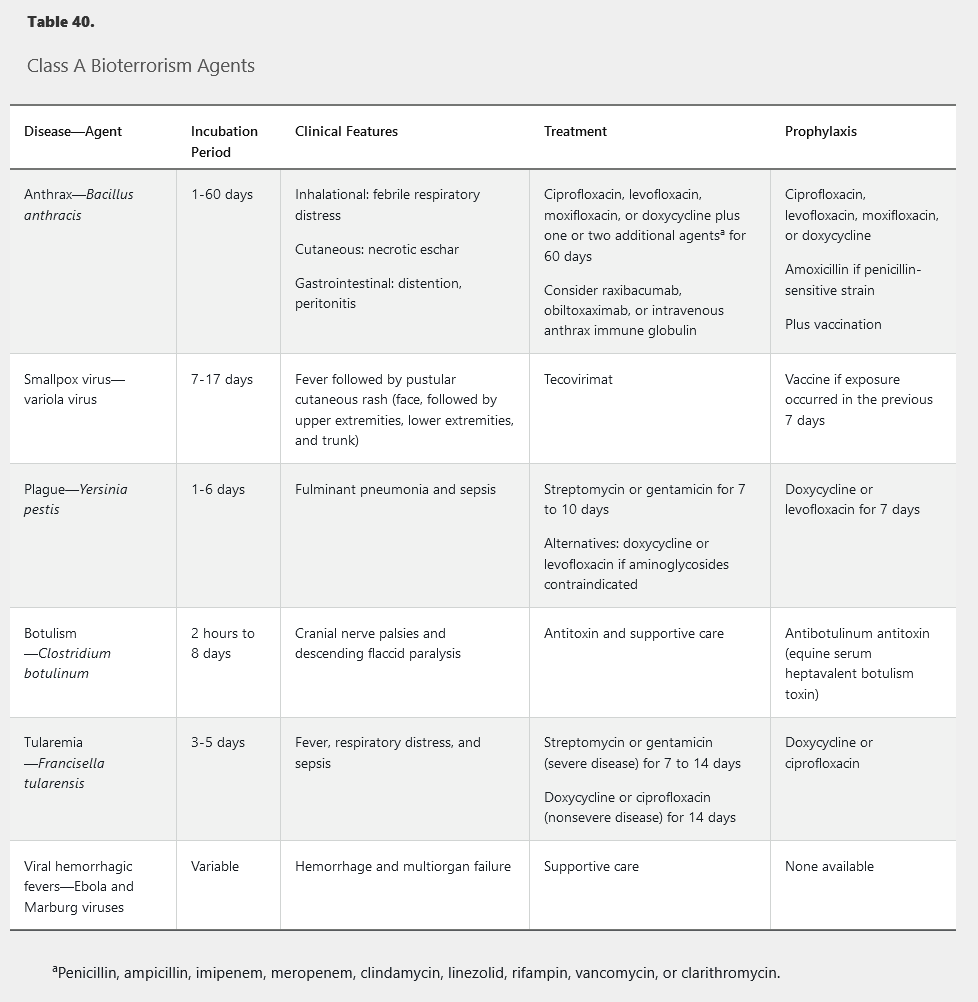

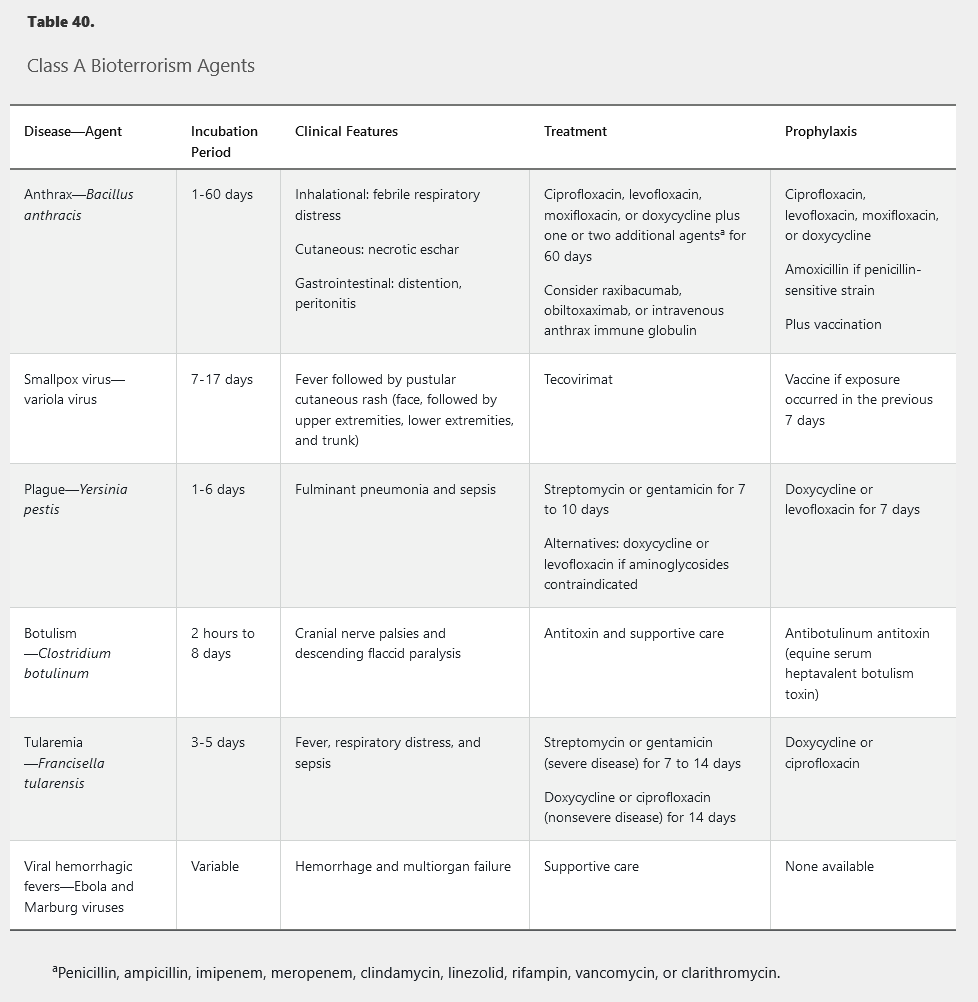

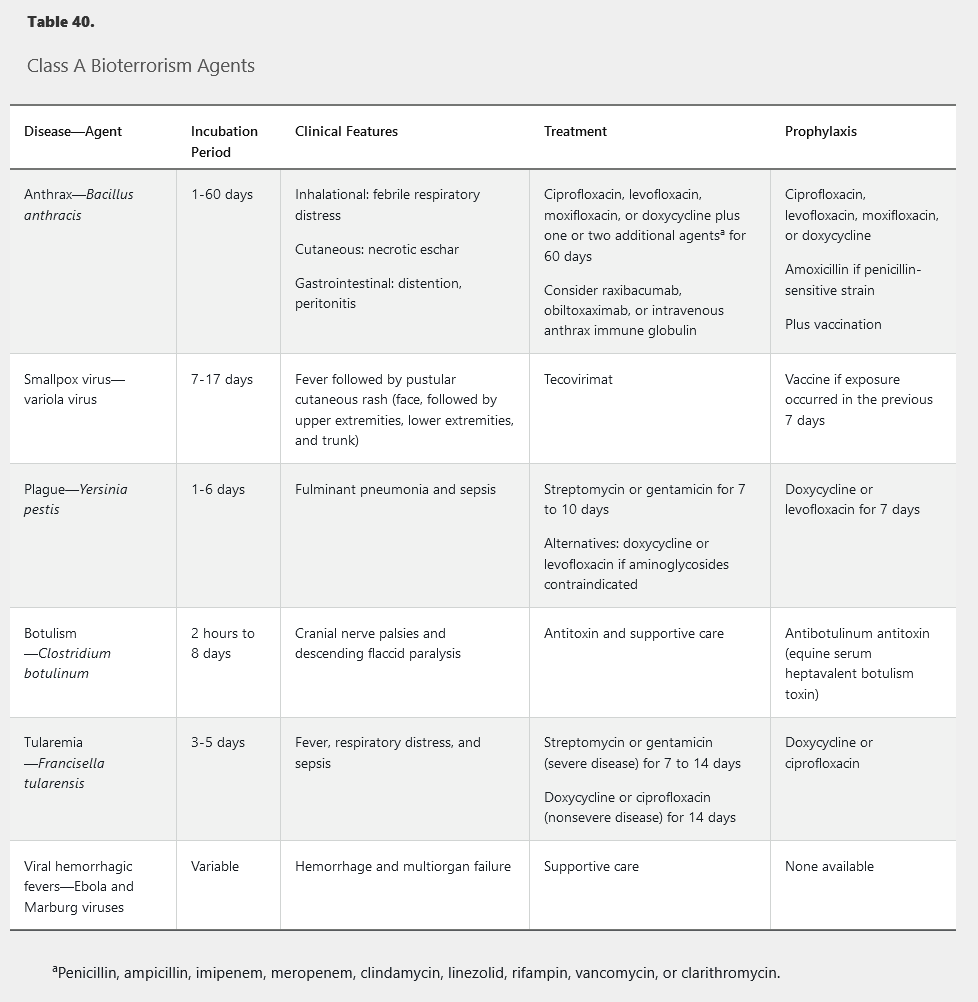

Unusually severe illness, rapid increase in disease incidence, atypical clinical presentation, and uncommon geographic, temporal, or demographic clustering of disease outbreaks suggest a bioterrorism attack. Bioterrorism agents are classified (Table 39) according to ease of dissemination, mortality rate, potential for public panic and social disruption, and need for special action for public health preparedness.

Anthrax

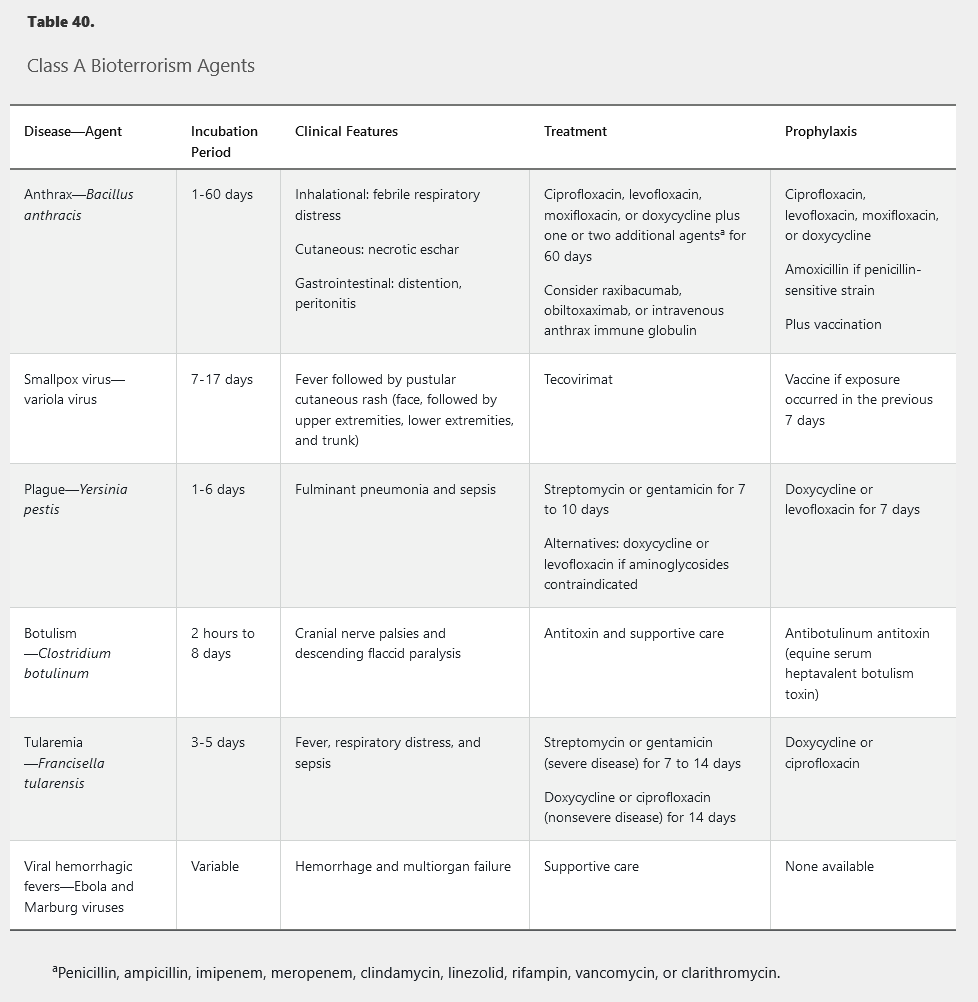

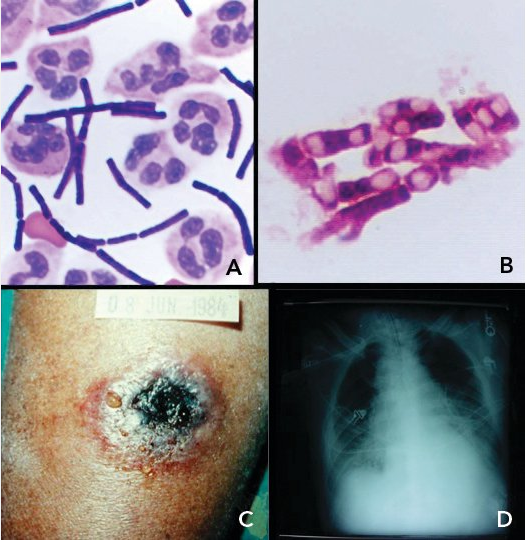

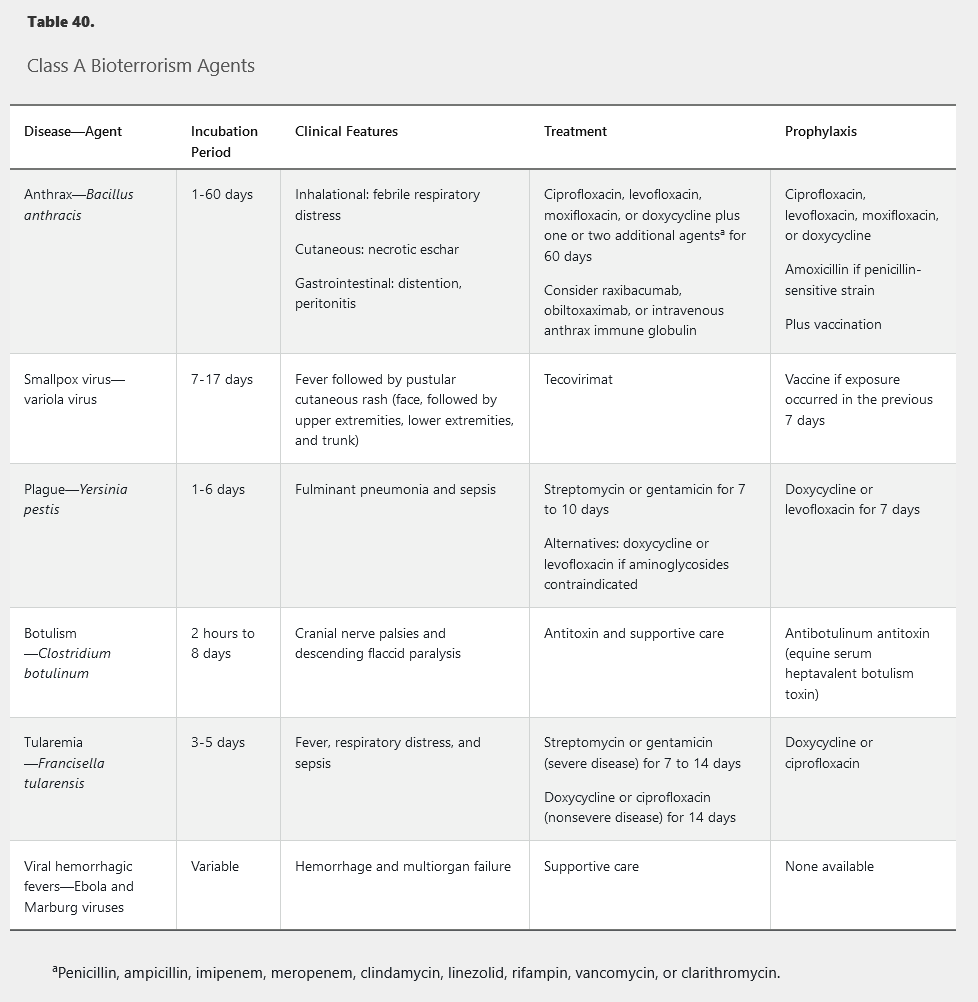

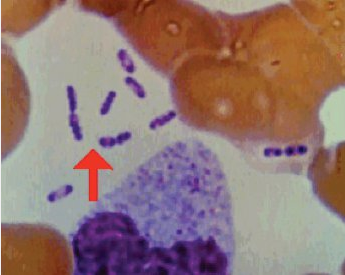

Anthrax infection is caused by Bacillus anthracis spores (Figure 15 panel A and Figure 15 panel B). Spores may be spread by aerosolization or in the mail, with infection following inhalation; any case of inhalation anthrax must be considered potential bioterrorism. Infection may also occur by cutaneous contact, with a characteristic black eschar forming (Figure 15 panel C), or by ingestion. Person-to-person transmission does not occur.

A, “box-car”–shaped, gram-positive Bacillus anthracis bacilli in the cerebrospinal fluid of the index case of inhalational anthrax resulting from bioterrorism in the United States; B, terminal and subterminal spores of B. anthracis; C, black eschar lesion of cutaneous anthrax; D, chest radiograph of a patient with anthrax showing a widened mediastinum caused by hemorrhagic lymphadenopathy.

A, “box-car”–shaped, gram-positive Bacillus anthracis bacilli in the cerebrospinal fluid of the index case of inhalational anthrax resulting from bioterrorism in the United States; B, terminal and subterminal spores of B. anthracis; C, black eschar lesion of cutaneous anthrax; D, chest radiograph of a patient with anthrax showing a widened mediastinum caused by hemorrhagic lymphadenopathy.

The clinical presentation of inhalational anthrax includes malaise, myalgia, fever, cough, dyspnea, and substernal chest discomfort. Meningitis occurs in up to 50% of persons. Rapid clinical deterioration leads to shock and death. Diagnosis is made by culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of blood, tissues, or fluid samples. Radiographic imaging reveals a widened mediastinum (Figure 15 panel D).

Treatment is outlined in Table 40. Toxin-neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies and anthrax immune globulin are approved for treatment and prevention of inhalation anthrax in conjunction with antibiotics. Postexposure prophylaxis consists of a fluoroquinolone or doxycycline in conjunction with vaccination.

In cases of proven or suspected anthrax in a family member, no specific treatment or isolation procedures are required for others in the household because spread in health care or household settings has never been demonstrated. In patients with confirmed or suspected bioterrorism-related anthrax exposure, postexposure prophylactic antibiotics, taken for 60 days, should be started as soon as possible. Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and doxycycline are the approved drugs for postexposure prophylaxis in adult patients. In pregnant women, ciprofloxacin is the drug of choice, and although tetracyclines are not recommended during pregnancy, doxycycline can be used with caution when ciprofloxacin is contraindicated. Therapy can be completed with amoxicillin if the isolate is found to be penicillin susceptible. Because of the possibility that residual dormant spores may become active after antibiotics are completed, three subcutaneous injections of anthrax vaccine should be given at 2-week intervals as part of postexposure prophylaxis.

Smallpox (Variola)

Routine smallpox vaccination ceased in 1980, after the World Health Organization declared the disease eradicated, leaving much of the world's population without immunity. Following inhalation, multiplication in regional lymph nodes results in viremia.

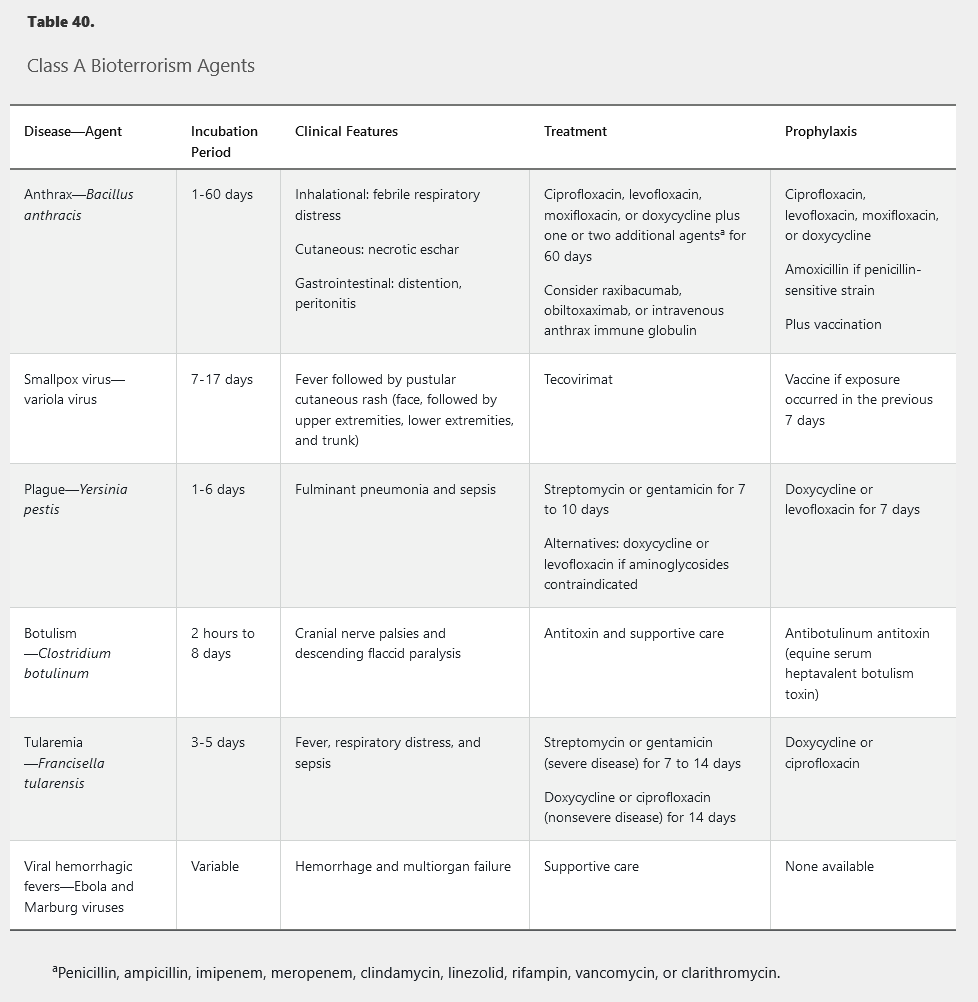

Secondary viremia occurs 1 week later, accompanied by fever, systemic symptoms, and rash, beginning with lesions on the oral mucosa and face and then the arms, legs, hands and feet, and to a lesser extent the trunk. Lesions evolve synchronously (same stage of maturation on any one area of the body) from macules to papules to vesicles to pustules before eventually crusting (Figure 16). Patients remain contagious until all scabs and crusts are shed. Mortality ranges from 15% to 50%.

Treatment is listed in Table 40. The oral antiviral agent tecovirimat was approved in 2018 for the treatment of smallpox in the event of a potential outbreak. Vaccination within 7 days of potential exposure is effective in preventing or lessening disease severity and should be provided to close contacts. Intravenous vaccinia immune globulin is indicated in certain vaccinia-related complications or when vaccination is contraindicated.

Ideally, vaccinia vaccination should be administered no more than 7 days (but preferably within 3) after the presumed exposure. In 1980, the World Health Organization declared that smallpox had been eradicated worldwide. However, because of its ease of deliberate airborne spread, highly contagious nature, and expected significant morbidity and mortality, smallpox has been identified as a member of the A list of potential agents of bioterrorism. Because routine childhood vaccination immunization is no longer required or recommended in the United States, most of the population is not immune. Smallpox vaccines are available in the event of exposure. Although none of these vaccines contains the actual variola virus, when properly administered the vaccines elicit a significant protective immune response. Although serious adverse events are a greater risk after administration of any live virus vaccine, including those containing vaccinia, persons at high risk for complications from replication-component vaccines are also at higher risk for severe smallpox. Unless the patient is severely immunodeficient (within 4 months of bone marrow transplantation, HIV infection with CD4 cell counts <50/µL, or severe combined immunodeficiency), the vaccine should be given. This patient's use of infliximab would not exclude him from vaccination.

Plague

Primary pneumonic plague occurs after Yersinia pestis (Figure 17) exposure through infectious aerosols and person-to-person transmission through respiratory droplets, which are likely scenarios for bioterrorism. Patients with suspected pneumonic plague require droplet precautions.

This Wright-Giemsa stain shows Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative coccobacillus with a “safety-pin” appearance (bipolar staining pattern).

This Wright-Giemsa stain shows Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative coccobacillus with a “safety-pin” appearance (bipolar staining pattern).

Bubonic plague is characterized by lymphadenopathy (buboes), fever, rigors, and headache. Chest radiographs are nonspecific. Gram stain and cultures of sputum and blood (performed using the highest level biosafety procedures) are often diagnostic.

Untreated, pneumonic plague is uniformly fatal. Treatment is outlined in Table 40. Asymptomatic persons exposed to aerosolized Y. pestis and close contacts of infected patients within the previous 7 days warrant postexposure prophylaxis. The available vaccine is ineffective at protecting against pneumonic plague. A live attenuated vaccine with protection from respiratory challenge is under investigation. Recommended first-line treatment is either streptomycin or gentamicin.

Botulism

Botulism may spread in a bioterrorism attack through inhalation or ingestion of botulinum neurotoxin after deliberate aerosol release or purposeful food contamination. Patients present with symmetric, descending flaccid paralysis with prominent bulbar signs (the “4 Ds”: diplopia, dysarthria, dysphonia, and dysphagia), which may progress to respiratory failure. Patients remain afebrile and mental status remains normal, but nausea, abdominal pain, and dry mouth often accompany the paralysis. Autonomic dysfunction may also occur.

Diagnosis depends on identifying the toxin from serum, vomitus, stool, gastric contents, or foods. Organism isolation is rare. Treatment is supportive (see Table 40). Antitoxin should be obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and administered promptly but will not reverse existent paralysis. Antibiotics are not useful.

Tularemia

Francisella tularensis transmission to humans occurs by vectors, direct animal contact, and inhalation; person-to-person spread does not occur. Abrupt onset of fever and respiratory symptoms follow inhalation of even a small inoculum of organisms. Chest radiographs demonstrate infiltrates, hilar lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusions.

Rapid diagnosis relies on serologic, immunohistochemical, and PCR testing; culture of tissues and fluids is low yield and potentially dangerous to laboratory personnel. Treatment is noted in Table 40. Death occurs in less than 4% of treated patients, with mortality rates reaching 30% in untreated pneumonic or typhoidal tularemia. No vaccine is available.

Viral Hemorrhagic Fever

The Ebola and Marburg viruses are the most likely to be used as biologic weapons. In endemic areas, spread to humans occurs by vectors, contact with bodily fluids, or fomites. Aerosolization is a likely mode of terrorist dissemination. Symptoms of fever, headache, myalgia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and unexplained bleeding and bruising appear 2 to 21 days after exposure. Disease progression results in maculopapular rash, hemorrhagic diathesis, shock, and multiorgan failure. Mortality rates can reach 90%. Persons are contagious only after symptom onset, but virus may spread by sexual contact in semen for weeks to months after recovery.

Depending on the stage of infection, diagnosis may be confirmed by virus detection in blood or other bodily fluids and tissues, antigen and antibody assays, and PCR. Exposed persons are monitored during the 21-day incubation period, with prompt isolation if symptoms develop. Treatment is supportive (see Table 40). Vaccine and antiviral medications are under development.